The Night Climbers of Cambridge

Why should Thomas Mailaender, a contemporary artist known for his impudent provocations, want to present us with photographs of students climbing on the roofs and walls of colleges at the University of Cambridge in the mid-1930s?

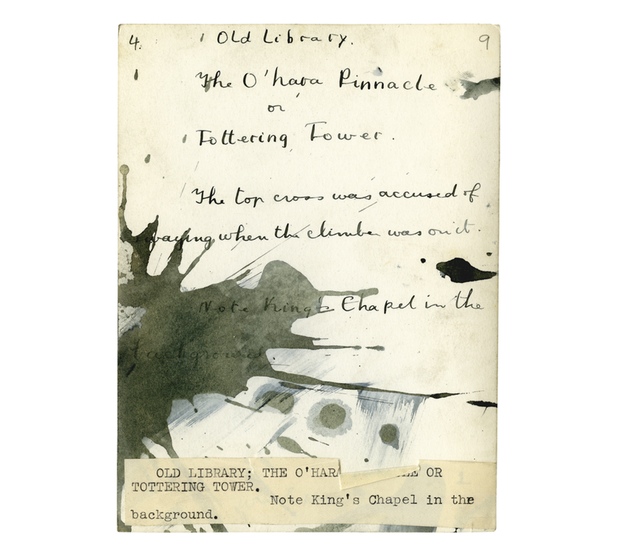

The Night Climbers of Cambridge was first published in 1937, by Chatto & Windus, a respectable publishing house in London. (The book, illustrated with photographs, was recently reissued by Oleander Press.) Mailaender, attracted by this peculiar venture, bought the original pictures and assembled them as a traveling exhibition. An odd choice, at first sight, but Mailaender has always been attracted by makeshift spoofs and charades. Nothing attracts him more than a tacky stunt where all the seams show. He is at home in the soft underbelly of the Internet, where self-satisfied egotists hog the limelight as they compete for delusional awards. In one noteworthy presentation he features as a beaming prize-winner holding on to outsize checks. He has a fondness for shaky facsimiles and rackety cover versions. His pictures of Algerian vehicles, piled high with possessions and discards, taken at the port of Marseille, look like nothing so much as a Joseph Beuys exhibition chanced upon in transit.

Mailaender is a saboteur. Bathos is his mode. His targets are credulity and complacency. He finds contemporary life, which includes contemporary art, ridiculous, pathetic, and entertaining. Long ago, before the night climbers plied their saucy trade on the walls of Cambridge, he would have been at one with Austrian writer Karl Kraus, who also appropriated pictures. Kraus’s leitmotif, you will remember, was the hanged body of the separatist Cesare Battisti displayed on a board in the moat of the Castello del Buonconsiglio in 1916 as part of a group portrait of executioners and accomplices all happy to be involved. Kraus saw it as a conclusive indictment of the Austrian Empire.

The Cambridge adventurers fit Mailaender’s bill precisely. Maybe they meant no real harm. All the same they were climbing, which was a man’s business carried out regularly and hazardously on rock faces in the Lake District and in Wales—and sometimes in the Alps and on Everest where George Mallory and Andrew Irvine came stylishly to grief in 1924. In this context fooling around on the buttresses of King’s College or St. John’s couldn’t be taken seriously. The night climbers, headed by Noël Edward Symington, were, one might think, asking to be held in contempt.

They weren’t even doing anything very unusual, for any amount of famous names had amused themselves on those famous walls—Geoffrey Winthrop Young, for example, a famous alpinist and author of The Roof-Climber’s Guide to Trinity in 1899. What set the new generation apart was its interest in publicity. They photographed themselves in action, using flash—which drew the attention of passing policemen. They were, that is to say, interested in staged events, and at the time such events were popular in the British press: studio pictures, for instance, of films in the making and of early TV shoots at London’s Alexandra Palace.

Meanwhile, in the real world the Spanish Civil War was in full swing—Guernica was bombed in 1937. In depressed Britain the government was at its wits’ end and the unemployed were up in arms—the famous Jarrow marches protesting unemployment and poverty also took place in 1937. The night climbers, cheeking the authorities and policemen, played their studiedly inconsequential part in this ghastly montage, and it is on this state of affairs that Mailaender has put his finger.

Thomas Mailaender will exhibit The Night Climbers of Cambridge this September at Roman Road Project Space, London.