Peter Berlin was the First “Photosexual”

If Narcissus—the famous character from Greek mythology—had been mentored by Peter Berlin, his story might not have ended in tragedy. After falling in love with his own reflection and then realizing that it actually wasn’t another person, Narcissus was so devastated by the prospect of never being able to experience true romantic love that he took his own life. But had he come of age in the early ’70s, when the tools of photographic reproduction were available to the general public, Peter Berlin’s example would have taught him that focusing entirely on your own image can be quite a satisfying substitute for traditional romantic love.

Berlin’s cultural contributions were so many decades ahead of his time and so unique—not fitting cleanly into either the world of art or the world of pornography—that understanding their relevance and impact requires the invention of a new terminology. I propose the word photosexuality and aim to make the case that Berlin was the first acclaimed male photosexual and the leading pioneer of its practice. As I see it, photosexuality is a contemporary mainstream sexuality in which erotic self-portraiture—the documentation of one’s own sex acts and the private and public distribution of those images—is intertwined so completely with one’s sex life that it becomes as important as the sex acts themselves and, in some cases, even more important.

In our all-encompassing social-media culture where, increasingly, no experience can be personally validated until it is publicly validated via online sharing, photosexuality has thrived. It has shifted the camera’s role from a tool used to document sexuality to that of becoming a sexual partner in and of itself. The mainstreaming of photosexuality is a fairly recent phenomenon, enabled and accelerated by four technological developments: online video streaming (from the mid ’90s until the mid 2000s); the iPhone camera (starting in 2007); GPS dating apps (Grindr, beginning in 2009); and Instagram (2010). For better or worse, these tools have enabled people all over the world to take their erotic representation and self-objectification into their own hands. The activity has particularly resonated with gay men and is now pervasive.

If you’ve sent a risqué picture of yourself to the cell phone of a current or potential sex partner, or shared a picture of a recent sex partner with a close friend’s cell phone to brag about your experience, or have uploaded a video of your sexual activity to Pornhub, or posted a sensual self-portrait on a beach in a thong, showcasing a perfect tan, feeling confident and beautiful, full of life, desire, and sexual pride and have then been satisfied by the pleasure of sharing this version of yourself with the audience you’ve cultivated, then you have engaged in photosexuality. And almost fifty years before these technologies made this commonplace at the dawn of the decriminalization of homosexual imagery, one determined man arrived there before all others. Peter Berlin’s unusual and extreme sexual-artistic practice made him the world’s first internationally famous photosexual.

Berlin’s two feature-length films took audiences with him on his personal evolution from sexual to photosexual. Nights in Black Leather (1972) is a cinema-vérité style self-portrait of an erotically vibrant young German immigrant experiencing his first tastes of the hedonistic sexual paradise of pre-AIDS, early 1970s San Francisco. In themes and structure, the film is an unexpected but direct predecessor to HBO’s megahit Sex and the City (1998–2004). In both the show and its two films, Sex and the City’s main character writes about her exploits after each encounter. Similarly, in Berlin’s film, he sits alone with his journal in a park, reporting on each experience. Like Carrie Bradshaw, a voiceover of Berlin reading his entries can be heard as he writes, sharing his self-examination.

After a period of cruising bars, streets and house parties, Berlin comes to the realization that “normal sex”—meaning sex in a bedroom with one partner—barely interests him. Throughout the course of the film he discovers the key elements he needs to get turned on: leather, public spaces, role-play, and exhibitionism. The film concludes with him journaling as his voiceover explains, “By now, normal sex seems so boring to me. I like much more to get into perverse trips . . . but as far as normal sex is concerned, one of the best experiences I have ever had was last week, when these two boys approached me at the gym. They asked me to come with them, because they enjoyed nothing more then having sex on a couch with spotlights aimed at them and an audience watching.” For Berlin’s rapidly advancing taste, “normal” has come to mean engaging with multiple partners for spectators. By the film’s end, he is finished with traditional sexuality.

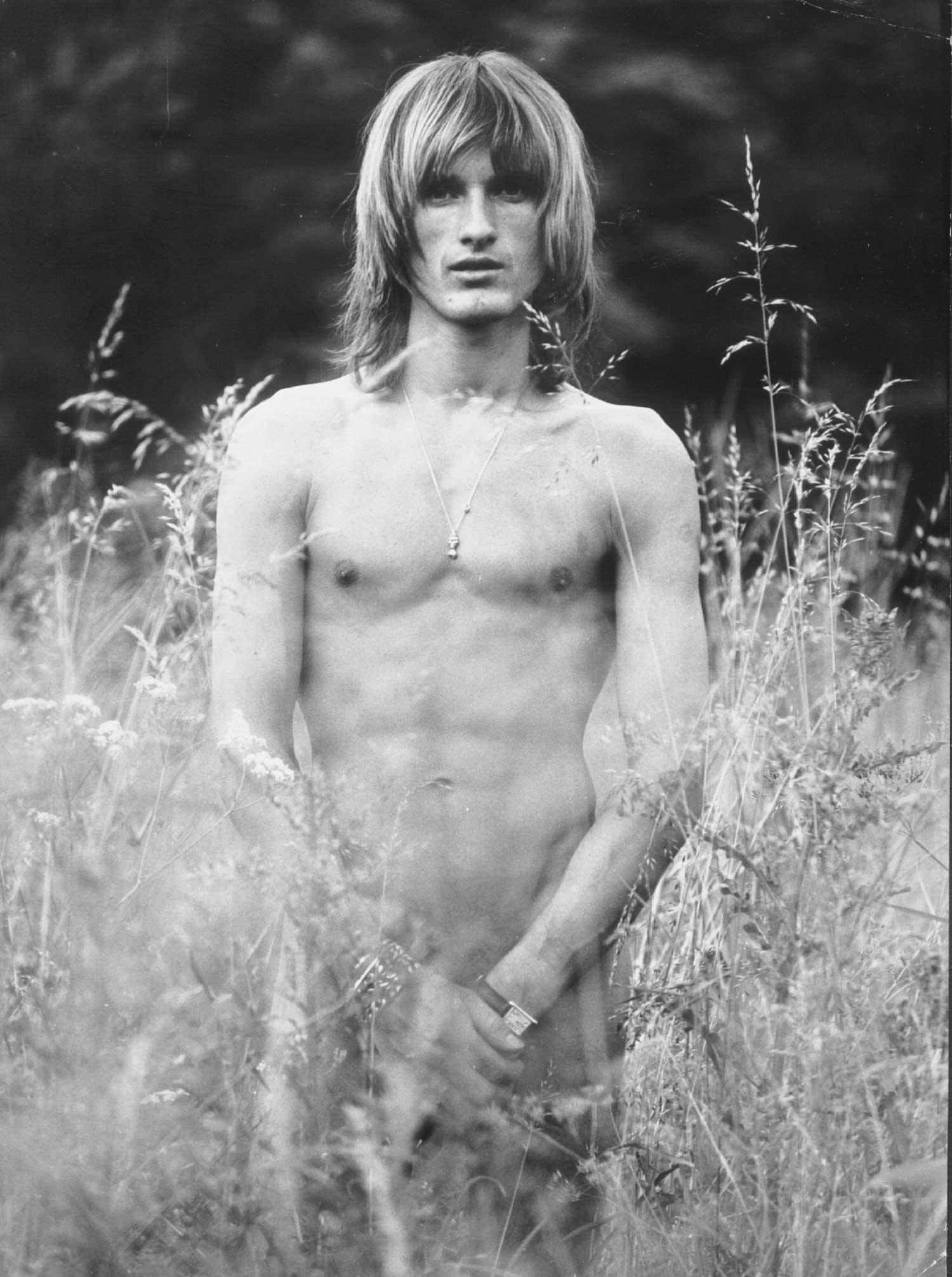

When Nights in Black Leather was released, it was embraced by an international audience of gay men desperately needing a role model to help them shed stifling patriarchal standards of masculine representation; and for Peter Berlin, the act of making the film was just as much of a guide as it was for his audience, helping him to sharpen his own uncompromised libidinous impulses. That project was the result of a collaboration with his friend and filmmaker Richard Abel. It leveraged the local celebrity Berlin had developed in San Francisco by creating a highly specific, incredibly confident hyper-homo persona, which he’d been performing and refining on the city streets for years. In conjunction with this public display, Peter had already been engaged in an elaborate and disciplined practice of erotic self-portraiture. His goal was not art, politics, or commerce. As he describes it, it was, simply, “chronicling the moments in my life when I felt the best.”

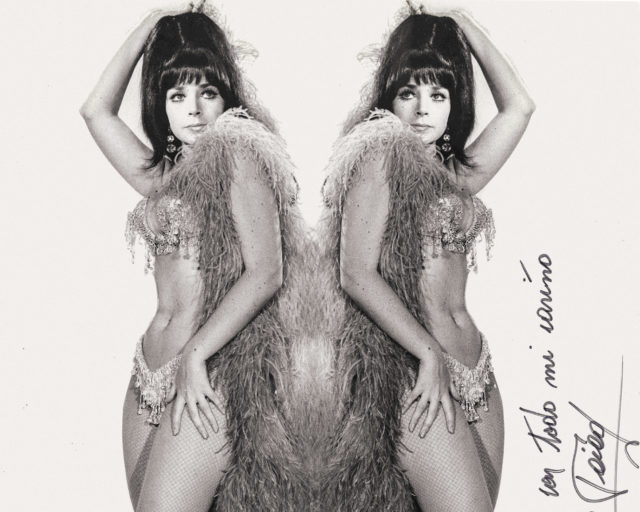

The success of Nights in Black Leather created more demand for Berlin’s image, so he monetized his private self-portraiture and developed a lucrative mail-order business. Through advertisements in gay publications, customers purchased photographs of Berlin for their own private pleasure. These new commercial endeavors allowed him to streamline his work further and enabled him to dedicate his time entirely to the few activities that enhanced his sexual pleasure: clothing design, photography, filmmaking, and cruising. On his own terms, he successfully turned his lifestyle into his primary revenue stream, which allowed his favorite practices to thrive. These unusual circumstances lead to the formation of a sexuality that established a profound and irreversible entanglement of dressing up, photography, and sexual fulfillment.

Of course, even then, the relationship between sex and the camera was far from new. Since its inception, the camera had been used to document the beauty and wonderment of the naked human form. What was new about Peter’s approach was that it was an independent enterprise. He wasn’t a muse for another artist or a model for a pornographer; nor was he a sex symbol produced by a film studio, like Garbo, Brando, or Monroe. He didn’t wait for an adoring and powerful benefactor to hand him the capitalist machinery of star production. As an out gay man, such tools were only available to his counterparts who had agreed to remain closeted for the purpose of becoming cultural icons. Berlin, on the other hand, valued himself and his sexuality with such militant pride that he took his identity into his own hands and became his own muse. “I wanted to turn myself into the type of man I wished I would see on the streets,” he has said as a way of explaining his style.

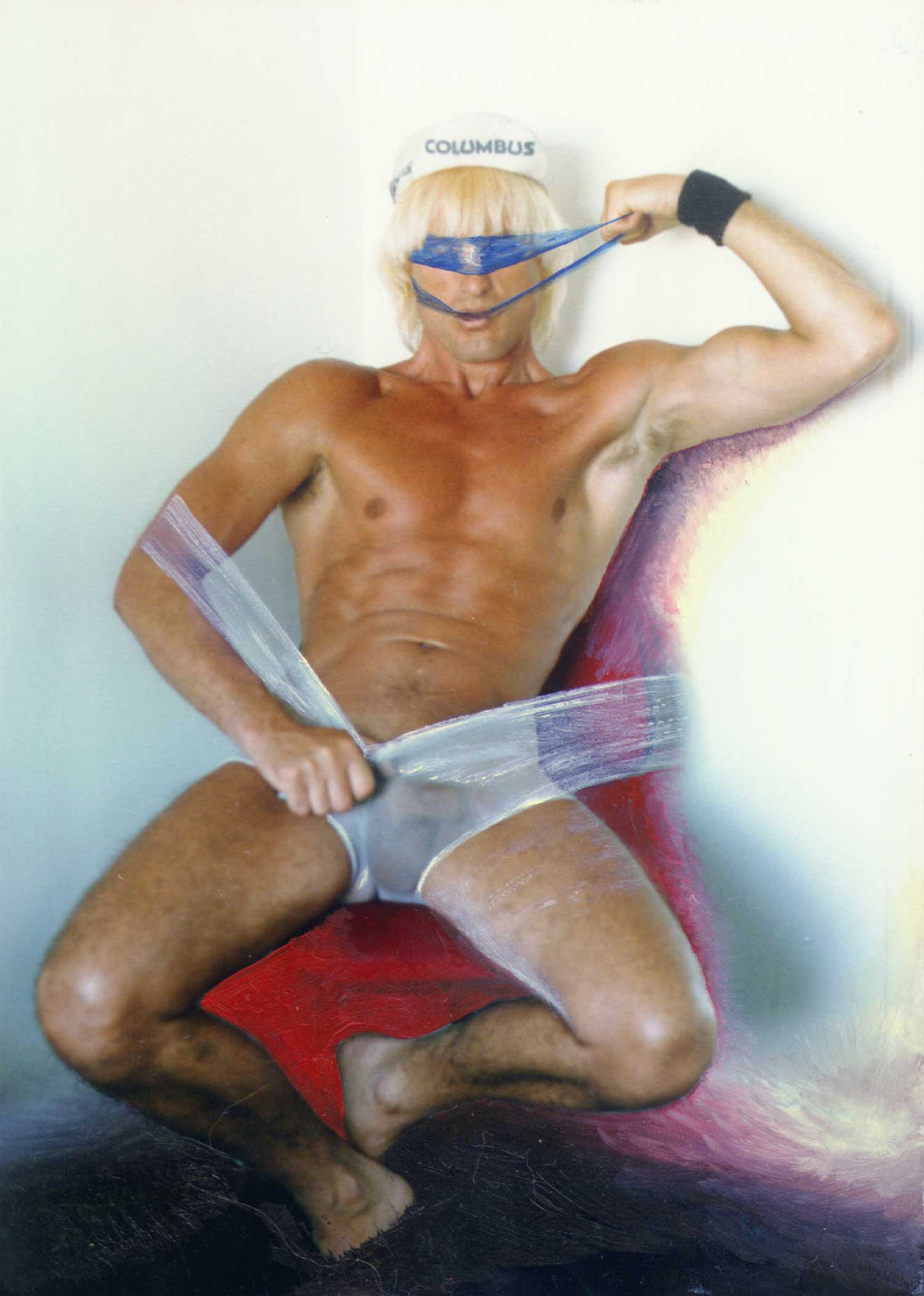

By the time Berlin’s second film came out two years later, the experience of making Nights in Black Leather and the response to it had given him a refined understanding of what he wanted from his sex life and the cinematic representation of it. For his next film, That Boy (1974), he stripped his filmmaking crew down even more sparsely, becoming his own director, producer, writer, and star. That Boy begins with Berlin cruising the daytime streets of 1974 San Francisco in a look that most hustlers would be embarrassed to wear at night: a leather biker cap that covered his signature golden pageboy locks, a tight black leather jacket that exposed his chest, a red bandana rolled up and knotted around his neck, dark aviator glasses, and custom self-tailored white sailor pants designed to showcase his crotch and elegantly cascade into thin bell-bottoms. In the film, a throng of Cockettes, the members of a queer theater collective who were known for their retro Hollywood or gypsy-like styles, parts for him, studying his look as he takes in theirs. Berlin struts through streets with determination until he encounters a handsome blind boy, the love interest of the film, who is dressed like a rocker and holding a cane. As he courts his new target, a paparazzi-style photographer appears out of nowhere to capture the young men flirting.

The photographer escorts Berlin (whose character is called Helmut) back to his studio. In a scene that is both sexy and hilarious, Berlin strips for the camera, taking off one layer after another and surprising the audience: no matter how skimpy the garment, there is always another skimpier piece beneath it. In this sequence and throughout all the sex scenes in the film, there are slideshow montages interspersed with the live action, a device that mimics the camera capturing an image. In this moment, desire is showcased traditionally through the presentation of firm young bodies intertwining; but mixed in between close-ups of stomachs, asses, and cocks are images of the camera flashing. And the camera flash becomes as important and as fetishized as the naked bodies. Finally, the room is covered with prints of Berlin. The shoot continues with him surrounded by hundreds of images of himself.

More naked young men join the photo shoot; they adore Berlin as he stands on a podium like a statue while the camera continues to flash. “I want to take pictures of them watching you,” the cameraman exclaims. “I want my camera to hold you all. To capture every one of you in its fine lens.” The climax of the scene has no penetrative sex or ejaculation. It ends with a slideshow of imagery hitting a rapid-fire pace. The erotic thrust of the scene is not traditional, not solely based on men’s enjoyment of each other’s bodies. It favors the camera’s actions and outcomes over penetrative sex or climax. Much more than just a simple pornographic film, through the lens of history, That Boy can now be understood as a photosexual manifesto.

Forty-four years after the release of That Boy, Peter Berlin is still a committed photosexual. What had grown out of instinct, desire, and circumstance had turned into its own distinct, long-lasting variant of sexuality. As the first photosexual, Peter Berlin gave a world starved of blatantly gay visual role models a new conception of the beautiful, empowered, self-loving, sensual, shameless gay man. Now that technology has allowed the mainstream to catch up with his project, thousands of gay men on Instagram are working toward achieving what Berlin already accomplished in the ’70s using only analog tools—his camera and the postal service. However, while social-media sharing of self-created erotic imagery might be a means to an end for today’s photosexual, Berlin’s work was always an equal companion to the live act of cruising. “Real for me,” he explains, “is when I walk the streets and you pass me, I look at you, you look at me, we pass each other, and then I look back, and you look back, and you stop. That’s real! That will never happen inside a computer.”

This essay is adapted from Michael Bullock’s new book, Peter Berlin: Artist, Icon, Photosexual, published by Damiani in November 2019. All photographs by Peter Berlin courtesy the artist and Damiani.