The Honesty of Petra Collins

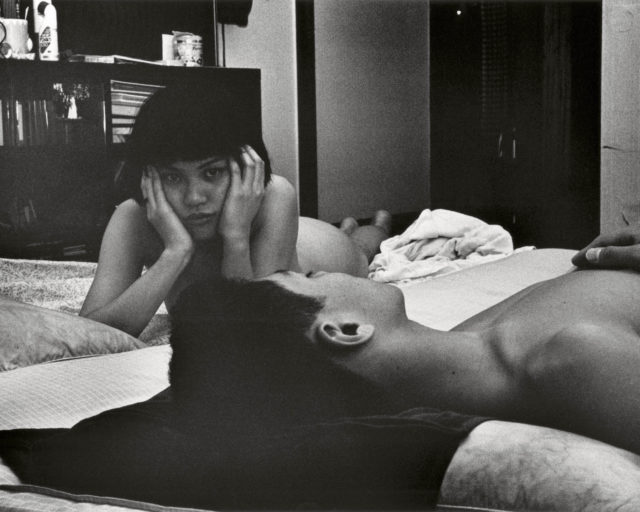

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

Petra Collins was five years old, in 1998, when Britney Spears’s “. . . Baby One More Time” was released. She was seven when Survivor first aired. She was almost eleven when Paris Hilton’s sex tape went public (conveniently, just a few weeks before Hilton’s television debut in The Simple Life), and eleven when Facebook launched. She was fourteen when Pornhub launched. She was seventeen when Instagram launched. She was nineteen when Kodak declared bankruptcy.

Collins’s generation—of which I’m a slightly older member—grew up in a cultural era defined by a potent combination of high commercialism and consumerism, seller enthusiasm and buyer naiveté. Seemingly caught off guard by new forms of media and technology, many still believed what they saw on the covers of magazines, on TV, on the internet, on their friends’ brand-new social media profiles. Sure, there was some baseline distrust of images—iconoclasm is as old as the icon—but savvy cynicism wasn’t quite as mainstream as it is today. It’s almost as if, in the late ’90s and early 2000s, it wasn’t fully understood, or maybe was simply ignored, that Photoshop is a powerful manipulative tool, that reality TV is an oxymoronic term, that the pictures from your ex’s vacation might not be telling the whole story. When Collins burst onto the scene at the start of this decade with her “real,” “raw,” “honest” photographic explorations of femininity, beauty, and sex, although she was borrowing heavily from many who came before her—Nan Goldin, Cindy Sherman, and Ryan McGinley, to name a few—it felt a little revolutionary.

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

Now, years later, but still just twenty-five years old, Collins has published Petra Collins: Coming of Age (2017), an attempt to put her meteoric rise to renown into a larger cultural and artistic context. Dubbed her first monograph, the book mixes Collins’s words and photographs with interviews, essays, and messages from other prominent voices, all reflecting on one subject: Petra Collins. Across the board, the guest contributors, from artist Laurie Simmons to writer Karley Sciortino, are unabashedly adoring. Model Diana Veras’s note begins, “Well first of all you’re fucking amazing and all your work has blown me away recently.” These sentiments would ring false, and their inclusion would feel tacky, if they weren’t expressed with such sincerity and urgency. What quickly becomes clear, when flipping through this book or browsing the comments section below a @petrafcollins Instagram post, is that many fans of Collins don’t just like her work; they’re thankful for it.

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

It’s this—the feeling that Collins has somehow given us something that we needed, or has finally said something that we’ve all been thinking—that has made her, for better or worse, a poster child. Having tapped into a wishful shift away from the inauthentic and fake, perhaps it’s no coincidence that her popularity has grown right alongside the recent revival of analog technologies like vinyl records and film cameras. Collins’s early work feels unmediated, like peeks behind the scenes. These images of teens hanging out, applying makeup, taking selfies—performing for their own cameras, not Collins’s—positioned her as a kind of visual truthsayer, an artist working to debunk the myth of the hairless body, the unblemished face, emotional invulnerability, uncomplicated happiness, perfect families, perfect romances, perfect lives.

But the most powerful force fueling Collins’s widespread fandom stems from her firsthand understanding of just how uniquely damaging it must be to grow up female in a Western world of false idols. (This is an experience I cannot directly speak to, but I hope it’s important for people of all genders to consider—with awareness and empathy—what it’s like to be a woman in a patriarchy.) Constructing a sense of self is a process of comparison, of establishing some idea of how one fits into the sociocultural context in which they live. So how could a young woman not feel alienation and shame when surrounded by imagery in which she fundamentally cannot see herself represented? But, to that same point, how could a young person of color not experience something similar? Or, for that matter, a young trans person of any race? Petra Collins: Coming of Age mostly features thin white women, a fact that feels incongruous with the goal Collins plainly lays out in her introduction: “This book is extremely personal, but I hope that when you look at it you can see yourself in it, too.”

Petra Collins, from the book Petra Collins: Coming of Age, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Rizzoli

The nagging question that will always sit just below the surface of any conversation about Collins is whether images, even ones made with an impulse to convey truth, can ever really be truthful, particularly because her photographs are celebrated for their “honesty.” That is, if Collins’s audience expects her to close the gap between who we are and how we are portrayed, are they bound to be disappointed? And if her mentality and work are, in large part, a reaction to feeling lied to by the images she was exposed to growing up, why should we trust images now, even hers?

Or maybe there’s another, more pressing question: If Collins is after honesty, at least in some sense, why is she a photographer? And why is she now working for fashion brands (Gucci, Bulgari, Juicy Couture) that are among the worst offenders of producing and propagating images that lie between their teeth? There’s a moment at the midpoint of Petra Collins: Coming of Age, in her dialogue with artist Marilyn Minter, that approaches an answer. Referring to media as the vehicle “that gives us all of our information,” Collins says, “It’s our duty to change it by working inside of it.” This statement of intent signals that her work, whether documentary or commercial, is never really without agenda. But it’s also an admission of her overall project’s inherent shortcoming—that her pictures are, at the end of the day, still pictures, part of the very thing they hope to undo.

Petra Collins: Coming of Age was published by Rizzoli in October 2017.