Photography is Miraculous

Kaja Silverman revises the history of a deceptive medium.

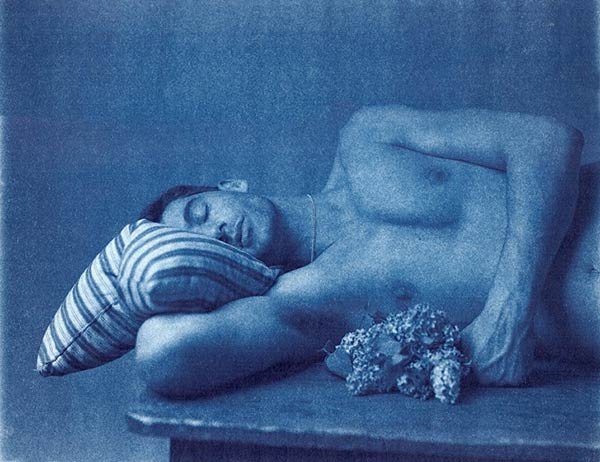

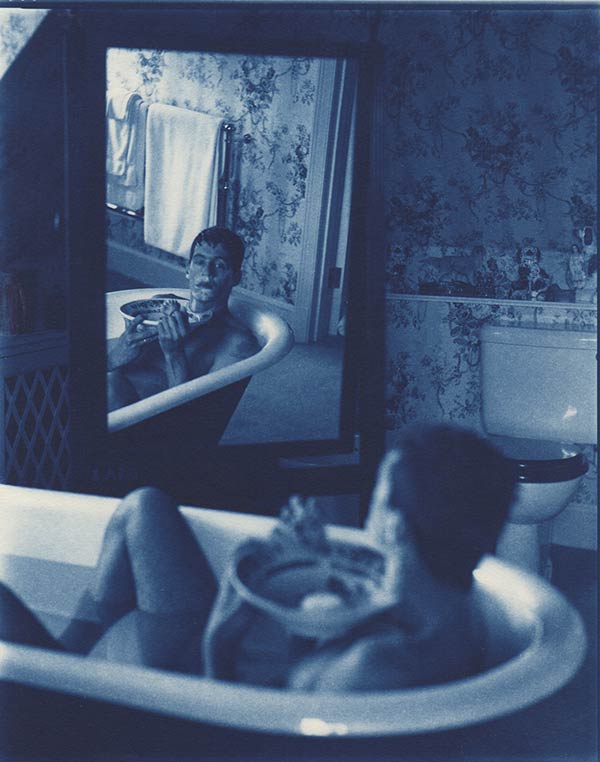

John Dugdale, Self Portrait with Lilacs for Walt Whitman, 1999. Cyanotype. Courtesy Holden Luntz Gallery

Two claims have come to dominate our understanding of photography: the photograph’s link to the past, and its indexical relationship to the external world. Kaja Silverman, professor of contemporary art at the University of Pennsylvania, sets out to challenge these axioms in The Miracle of Analogy (2015), the first in a two-volume history of photography. Unlike much of her of her earlier writing, however, Silverman doesn’t roll out her argument with her usual lucidity—she makes you work for it. She also assumes a fairly good working knowledge of phenomenology.

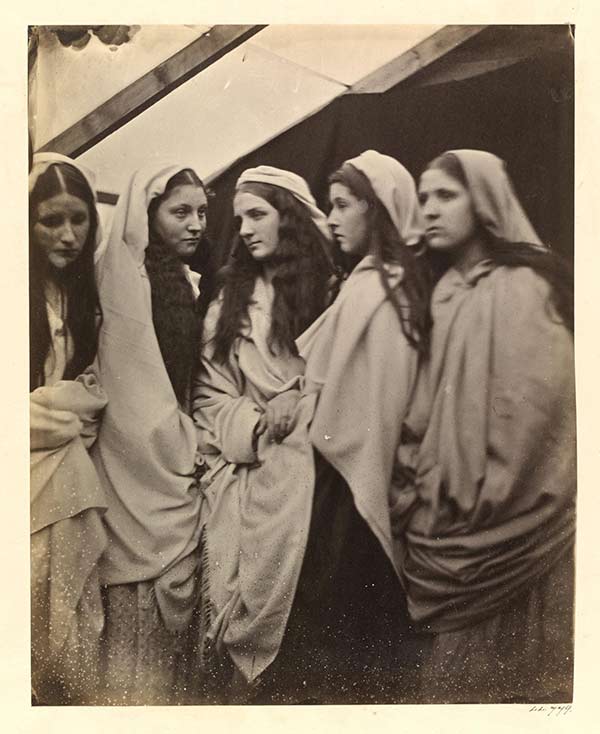

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Five Foolish Virgins, 1864. Courtesy the Victoria & Albert Museum

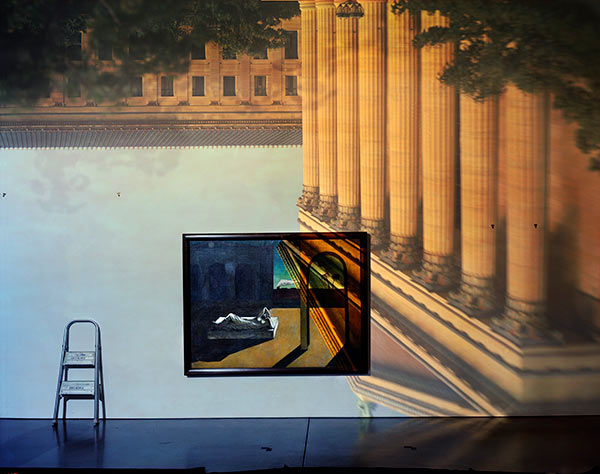

Nowhere in the book, for instance, is there a categorical definition of analogy; instead, it’s inferred through a series of historical and contemporary case studies. For many Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers, for example, the camera obscura, an enclosed box or room into which images of the outside world were projected through a lens or small aperture, was understood as an analogy for the human eye—a darkened chamber for gathering visual impressions emanated by objects in the world. Early discussions of the camera obscura conceived of the image as something that was received by the subject rather than taken. It was only with the introduction of increasingly precise lenses in the seventeenth century that the camera obscura began to be appreciated as an instrument for capturing and stilling the flow of images rather than a medium for revealing analogies. And alongside this shift from receiving to capturing emerged the corresponding notion that the image did not originate in the world, but in the intentions of the subject who took the photograph.

Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura: The Philadelphia Museum of Art East Entrance in Gallery with a de Chirico Painting, 2005 © the artist and courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York & Zürich

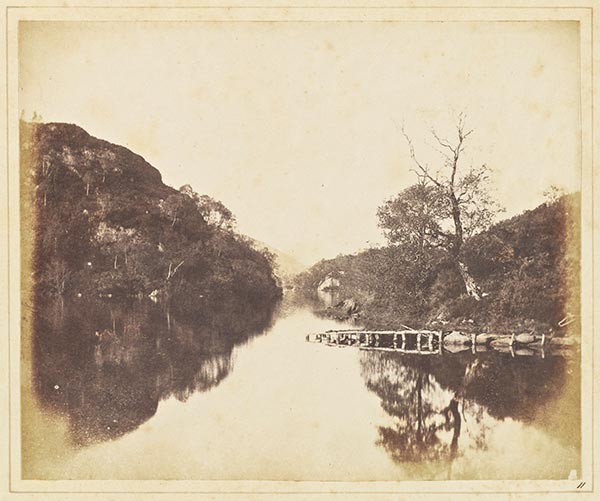

To insist on the photograph as something taken by the subject, Silverman writes, is to think of it as somehow separate from the rest of the world. This implies that the subject taking the photograph is outside of the world looking in, and that the camera is an instrument of control, a tool for mastering the world by creating visual representations. Early experiments in chemical photography were prompted by this imperative to control, to still the stream of moving images that entered the camera obscura. But early photographs, as Silverman shows, were often fluid, unsettled objects. The image that eventually appeared was far from instantaneous: exposures took up to eight hours, and the glass plate or paper negatives had a tendency to carry on developing (or, alternatively, to disappear) even after the fixing process. Because the photograph represented more than one moment in time, it acted as a “trans-temporal” object, evolving “in tandem with the world,” and never reaching what we would now consider to be a finished, permanent state.

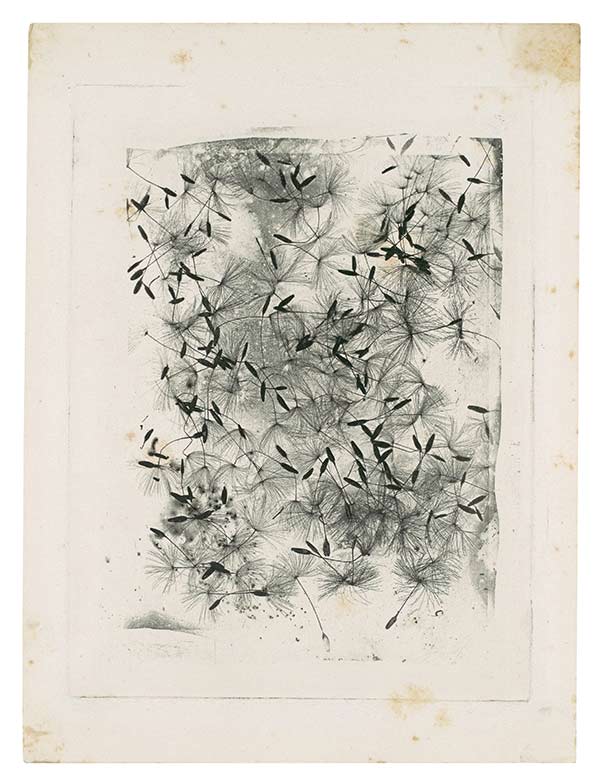

William Henry Fox Talbot, Dandelion seeds, ca. 1858. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art

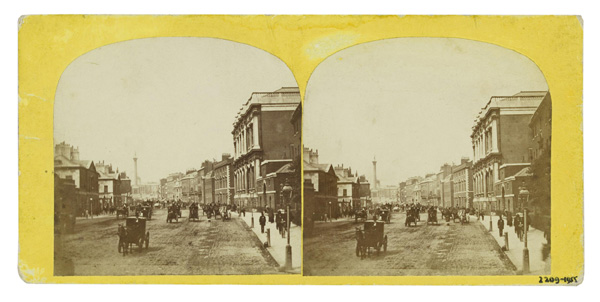

Similarly, before the positive became the privileged form, positive and negative images were regarded as equally valid depictions of the world. William Henry Fox Talbot, credited with the invention of the calotype process in 1841, understood his first negative images as full-fledged photographs—portraits that worldly forms made of themselves—rather than as templates from which positives could later be produced. Silverman likens this relationship to the philosophical notion of the chiasmus. Proposed by French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the chiasmus describes the thread of shared experience that unites the person seeing and the object seen, that links “the toucher to what is touched, and sign and visibility to touch and tactility.” The essential reversibility and reflexivity that defines the chiasmus is also embodied in the stereograph, an early form of three-dimensional image. As Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. wrote in 1859, the stereograph’s illusion of three-dimensionality allowed the viewer to “feel” their way around the depths of the image. However, it also permitted the unpleasant sensation that the pictured objects were reaching out into the viewer’s space.

Unknown photographer, Stereoscopic photograph of Parliament Street, looking towards Trafalgar Square, with Whitehall in the foreground, ca. 1850–80. Courtesy the Victoria & Albert Museum

The reflexivity that defines photography is also aligned, Silverman suggests, with the essential reversibility that defines and binds us together as human subjects: the associations, similarities, and resemblances that link the photograph to the world are the same ones that shape our existence. We experience our own visibility through the gaze of others. In spoken language, our sense of shared being with others is expressed through the “reversible and mutually defining” pronouns I and you.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Loch Katrine, 1844. Courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program

The Miracle of Analogy is more than an alternative history of photography. Silverman makes a number of provocative claims that unsettle not just the perception of photography as a human invention, but our certainty regarding the place of the human subject as master of the visible world. The photograph, Silverman suggests, is “the world’s primary way of revealing itself to us”—a vehicle for disclosing the analogies that bind all of creation together. As such, photography is, and has always been, part of the world—something that we have discovered, not something that we’ve created. Agency, moreover, is not unique to human subjects, it is also innate in the objects in the world that show themselves to vision, and that do so differently to the camera than they do to the human eye.

John Dugdale, Self Reliance, 1998. Cyanotype. Courtesy Holden Luntz Gallery

The industrialization of photography, on the other hand, is aligned with the philosophical drive—originating in the Enlightenment philosophy of René Descartes—to ascribe agency to human subjects alone, to establish the subject as the origin of the visible world and the creator of meaning. If this rupture between subject and world, as Silverman argues, has also come to dominate histories of photography, then The Miracle of Analogy seeks to restore to photography what history has stolen from it: its sense of interconnection with the world, and the camera as a means of experiencing the world rather than simply a tool for documenting it.