Picturing Utopia, From Shakers to Hippie Communes

A visual record of American longing and discontent.

Justine Kurland, Waterfall Lesson, Drawing a Stick Figure, 2007

Courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

And I John saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her bridegroom. —Revelation 21:2

And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the Garden. —Joni Mitchell, “Woodstock”

Utopia is invisible. Only the utopian can see it. Take, for instance, Nathan Meeker. In 1844, soon after graduating from Oberlin, Meeker joined the Trumbull Phalanx, a community of two hundred fifty men and women in the wilds of eastern Ohio that was modeled on the ideas of the French visionary Charles Fourier. Fourier believed that if women were emancipated, labor was organized according to his elaborate specifications, and everyone gathered into cooperative communities of precisely 1,620 (called phalanxes), then the world would be briskly transformed into a paradise he called Harmony. In Harmony, he prophesied, every human impulse, even the most taboo sexual predilection, would be satisfied and rendered productive; abundance would prevail; friendly whales would tow our ships; and the oceans, tinctured by “boreal fluid” from the melting Arctic icecap, would taste like lemonade. Fourier’s ideas—pasteurized of their erotic digressions by his American translators—became so popular in the United States that twenty-nine American phalanxes were established during the 1840s and ’50s. New Jersey’s North American Phalanx, the ruins of which are pictured here, lasted the longest, from 1843 to 1855.

Charles François Daubigny, View of a French Phalanstery (lithograph), 1800s

Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris/Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library

One spring afternoon at the Trumbull Phalanx, young Meeker sat down with his notebook and took stock of his new home:

Seating myself in the venerable orchard, with the temporary dwellings on the opposite side, the joiners at their benches in their open shops under the green boughs, and hearing on every side the sound of industry, the roll of wheels in the mills, and merry voices, I could not help exclaiming mentally: Indeed my eyes see men making haste to free the slave of all names, nations and tongues, and my ears hear them driving, thick and fast, nails into the coffin of despotism. I can but look on the establishment of this phalanx as a step of as much importance as any which secured our political independence; and much greater than that which gained the Magna Carta, the foundation of English liberty.

Looking upon the most mundane tableau of rural life, Meeker saw the transformation of the world. If he had been carrying a camera rather than a pen, the picture he would have taken would be indistinguishable from one taken in any other American village: a dusty orchard, a gristmill, men and women hard at work. The gulf separating what the believer sees and what a camera can record haunts every photograph of utopian living. Some images deliberately try to bridge this gulf by approximating on film what the utopian sees. An image of the theosophist community at Point Loma—shot from below and at a distance like the dream of a shining hilltop city—is a perfect example. Other photographs make the gulf itself their subject.

North American Phalanx, Country Route 537, Monmouth County, New Jersey (photographer unknown)

Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Utopia, as its most ardent citizens see it, may be camera-shy, but images have always been the lifeblood of utopianism. In the past those images have usually existed in the form of fiction, that meters-long shelf of novels describing life in the perfect society. These books typically recount the adventures of a wide-eyed, sunburnt explorer as he stumbles upon a delightful yet unknown nation. As he drifts about, chatting up the locals and taking in the sights (often falling for some winsome utopian lass), the explorer narrates in detail what life in utopia looks like. How do the utopians get to work? What color are their costumes? Are their streets clean? If the novel is any good, the shape and texture of life in utopia slowly forms in the reader’s imagination. The whole point of writing a utopian novel—instead of, say, a political tract on the virtues of universal education and collectivized agriculture—is that fiction can render ideas visible, allowing us to evaluate the author’s particular notion of the ideal society by the most intimate criterion: can I picture myself living there?

Rachel Barret, Zoe, 2009

Courtesy the artist

There are as many utopias as there are utopians, but two general visions of paradise tend to dominate the communitarian mind. These two visions are probably as old as human imagination, but their most influential formulations, at least in the West, come from scripture, where they form the bookends of biblical history. In the beginning, it is written, God planted a garden eastward in Eden. And with it was planted the half-remembered dream of a bountiful, property-free existence in the venerable orchards of Paradise, a life uncorrupted by capitalism, technology, or pants.

History, as the Bible tells it, might begin in a garden, but it ends in a metropolis: the gleaming, prefab city of New Jerusalem that God will lower down to earth at the time of the millennium (the thousand-year reign of heaven on earth). For those utopians who do not take the Book of Revelation literally, the prophecy of New Jerusalem has been swapped for (or merged with) the Enlightenment’s promise of ceaseless human progress, the belief that science and reason will someday usher humanity into an orderly, air-conditioned paradise of comfort and fraternity.

Photographer unknown, Raja Yoga Academy and Aryan Memorial Temple at the International Theosophical Headquarters, Point Loma, California, 1919

Over the last few centuries no place on the globe has been more crowded with utopian longing than North America. Since its “discovery” by Europeans, “the fresh, green breast of the New World,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald described it, has stirred dreams of abandoning the crumbling edifice of the Old World to build the perfect society from scratch. At the outset most of this thinking was theological. Many early visitors to the New World (including Captain Columbus himself) believed that they had arrived at, or at least near, the “historical” location of Eden. Many others, including the Shakers and Oneida Perfectionists (whose communal home is pictured here) believed that the young American republic would be ground zero for a new dispensation of social perfection. They believed that this was where the millennium was slated to commence (or had already commenced) and that it was up to them to begin building the perfect society, their own New Jerusalem.

A group of Oneida Community Perfectionists posed in front of their communal home, the Mansion House, ca. 1875

Courtesy Oneida Community Mansion House

The first major wave of communal utopianism in the United States peaked just before the widespread availability of pho-tography (roughly 1820–50, with a lull in the 1830s). During this era, utopians such as the textile magnate Robert Owen and the apostles of Fourier broadcast their visions of a secular, cooperative New Jerusalem using paintings and lithographs. These technical-looking images of the ideal city were printed in utopian newsletters and Whig broadsheets like the New York Tribune and hung on the walls of “associationist” clubs and workingmen’s halls. Owen, who came to the United States from Scotland in 1824 to found Indiana’s New Harmony community, was the canniest of the utopian propagandists. He commissioned a British architect to build an elaborate, six-foot-square model of the “parallelogram” that he intended to build on the Western frontier. Owen’s parallelogram, like Fourier’s “phalanstery,” was essentially an entire city contained in a single building, a sprawling, high-tech palace for the people. John Quincy Adams was so captivated by Owen’s model that he displayed it in the White House during the winter of 1825.

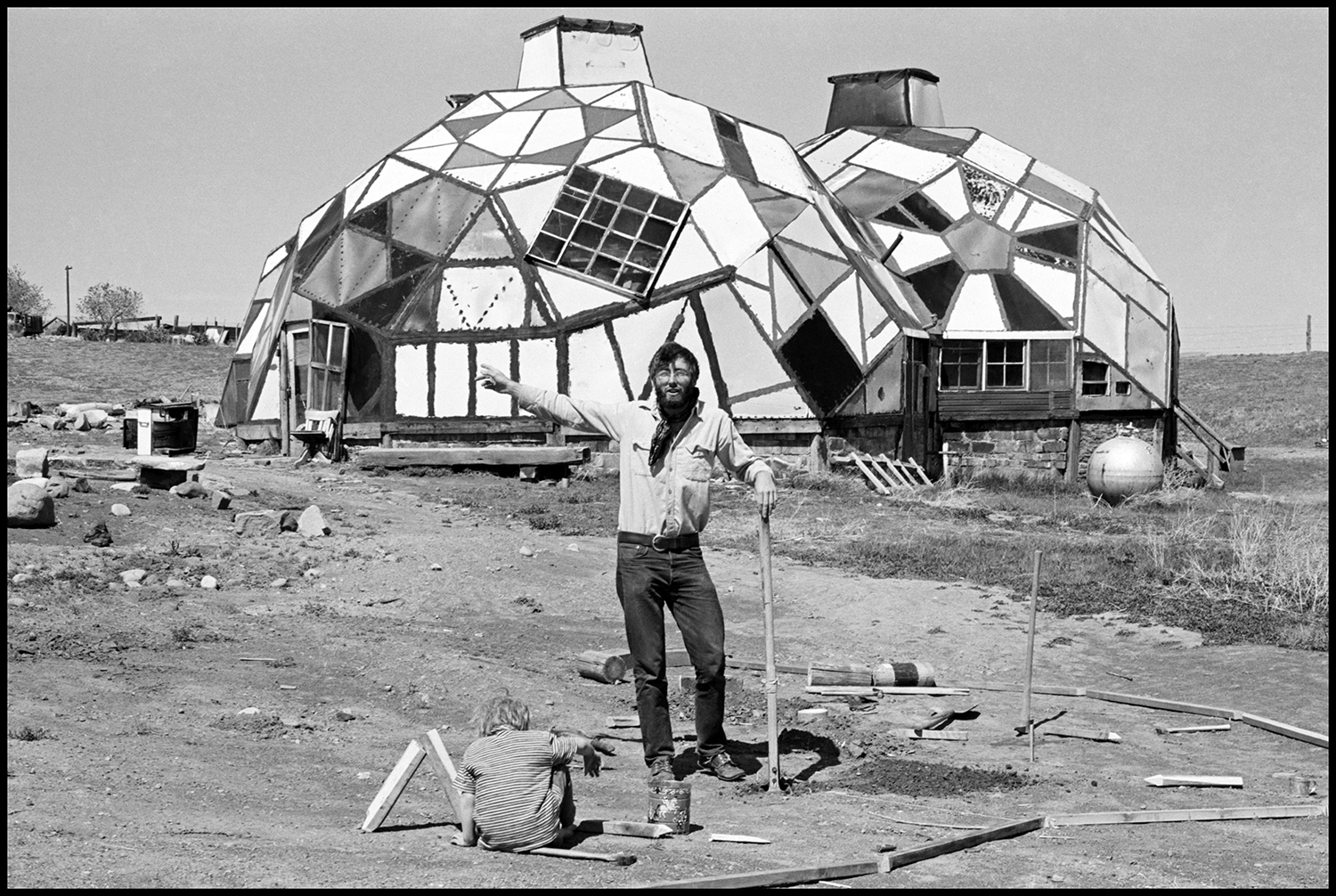

Dennis Stock, Drop City Artists’ Commune, Colorado, 1969

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

These pre-photographic images, projected straight from the imagination onto the page, helped inspire thousands of Americans to pursue the dream of building a New World utopia. The immense scale of the structures dreamed up by Owen and Fourier mirrored the grandiosity of their aspirations. As Meeker’s letter makes plain, the utopians of the mid-nineteenth century aimed for nothing less than a peaceful, worldwide revolution. Their logic was simple: if they could build one working model of the perfect society—a society founded on cooperation rather than competition—its shining example would inspire rapid and endless duplication, or, as one Fourierist optimistically put it, “thousands of analogous organizations will rapidly arise without obstacle and as if by enchantment around the first specimens.” This was how they planned to trigger a secular millennium. “The only practical difficulty,” Owen wrote with typical breeziness, “will be to restrain men from rushing too precipitously” into the new utopia.

A century later communitarian fever once again swept the United States. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, after the scene went sour in the East Village and the Haight, longhaired youths flocked to the remote counties of New York, California, Colorado, and New Mexico to build their own small utopias. Although they tried and often succeeded to build strongholds of consciousness and fraternity amidst the competitive bustle of American life, they rarely spoke, as their utopian forebears had, of global transformation. The dream of an American New Jerusalem was, for the most part, replaced by the search for a new Eden, a paradise walled-off from the fallen world.

Lucas Foglia, Victoria Bringing in the Goats, Tennessee, 2008

Courtesy the artist

The buildings tell the story. The “unitary dwellings” of the nineteenth-century utopians—the fanatically symmetrical Shaker dormitories, the ornate Oneida “Mansion House,” and Fourier’s (unrealized) Versailles-like phalanstery—were replaced, in the 1960s and ‘70s, by Drop City’s improvised Fuller Domes (called zomes), the scattered teepees of the New Buffalo Commune, and the assorted yurts, lean-tos, and chicken coops of countless backwoods communes. Like the nineteenth-century utopians, the hippie communards built homes intended to expand the meaning of the word “family,” but their ambitions were more modest, more spontaneous, and more realistic. They did not attempt to supplant the dominant institutions of America or “free the slave of all names.” They simply aspired to take leave of what they regarded as a repressed, faltering culture. (The lysergic cheerleaders at the vanguard of the psychedelic revolution are an interesting exception. Their rhetoric of instantaneous global awakening occasionally echoed the high-flown prophecies of utopians like Owen and Fourier.) Even those communes that were expressly organized around political activism did not regard cooperative living as the chief lever of social change. For them, communalism was a means—an inexpensive place to crash between marches—not an end.

On its face utopianism is a way of thinking about the future, of picturing, in H. G. Wells’s elegant phrase, “the shape of things to come.” For this reason, photographs of old utopias may seem quaint in the way that all antique visions of the future can. And yet, building or imagining a utopia is not only a way of thinking about the future, it is also a way to organize our grievances with the here and now, to nail our complaints to the wall. Nobody tries to build a new society if they like the one they live in. Seen in this light, the utopian experiments of the past offer up a surprisingly accurate psychological history, a chronicle of each era’s most acute frustrations. While these images may not reveal utopia as it was seen by fervid dreamers like Nathan Meeker, they present us with something just as valuable: a visual record of American longing and American discontent.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 209, Winter 2012.