Picturing Warmth and Belonging in Muslim Communities

Mahtab Hussain’s portraits from Baltimore to Los Angeles reflect the diversity of what it means to be an American Muslim today.

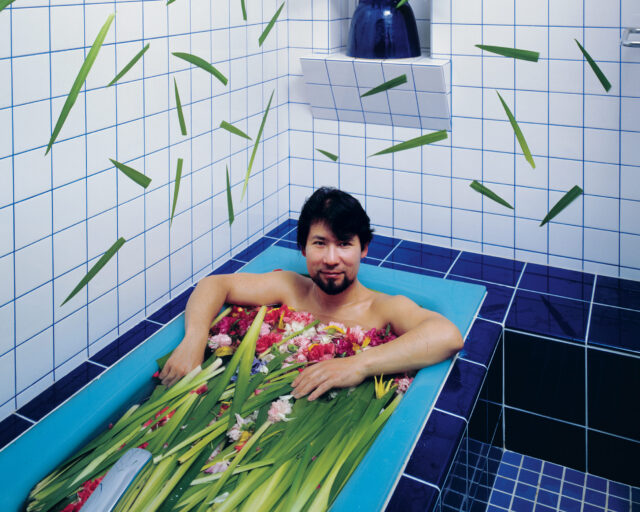

Mahtab Hussain, Tahira Queen, Baltimore, 2023

The first night he arrived at his new apartment in Baltimore, last year, Mahtab Hussain—in town for a residency at the Maryland Institute College of Art—noticed the sound of the azan, the traditional Muslim call to prayer. “I stood on the desk and opened the window to hear where it was coming from. That was the only time I heard it from my apartment,” he told me recently. “It felt like a sign.”

Hussain, a portrait photographer who has been documenting how Islam is lived in his native Britain for the last fifteen years, didn’t expect to be confronted with a Muslim presence in his temporary hometown so soon. “It cemented the idea that I had to make work in Baltimore,” he says. Immediately, Hussain started to map out the local mosques. Five were a bike ride away, among them Masjid Ul Haqq, first established in 1946 under Elijah Muhammad, at the time the leader of the Nation of Islam. (Its congregation has since shifted to a Sunni practice of Islam.) Hussain visited Ul Haqq the next day.

A prayer call had incidentally set in motion the latest installment of Hussain’s ongoing project to bring visibility to a community that is habitually underrepresented in the arts and misrepresented in the public imagination. “I want to visually articulate what the American Muslim experience is,” he says, “and make people look at Muslims in a different way.” His series Muslims in America (2021–ongoing) has already generated segments in Los Angeles, Toronto, and New York, distinct portfolios reflective of the diversity of what it can mean to be an American Muslim today. Muslims in the United States aren’t monolithic, the series proclaims; they resonate, instead, with idiosyncrasies from one town to another, like the living communities they are. If the images’ subjects in New York are strikingly queer and Toronto’s are predominantly Middle Eastern, Hussain “quickly realized Baltimore was going to be a Black experience.”

Even though African Americans account for more than a fifth of the US Muslim population (a number that is growing), the validity of their faith and the role it plays in strengthening the social fabric of vulnerable neighborhoods across major cities is rarely acknowledged. For Hussain, Baltimore’s Black Muslim minority—routinely ignored by the city’s other Muslim communities, not to mention by society and culture in general—stood out as an ideal subject.

Hussain found the vitality of his Baltimore sitters’ religious practice and their networks compellingly at odds with the grim reality of where they lived: marginalized neighborhoods with names such as Cherry Hill and Upton/Druid Heights. “The poverty and the violence is right there for you to see,” Hussain observed, adding that while in the United Kingdom the aggressive stance of the male youths he portrayed tended to be performative, “in Baltimore, you actually feel your life is on the line.” At the same time, Hussain was struck by the warmth, sense of belonging, and empowerment he encountered in Maryland: “Islam really connects with these young men and women, giving them a grounding and peace they badly need.” The religion derived hope Hussain found among individuals who regularly lose friends to drug abuse and gang violence affected him personally.

It’s no wonder that a sense of pride emanates naturally from the people in Hussain’s photographs, who are, for once, being seen rather than vilified.

While Baltimore’s Muslim fellowship embraced the forty-two-year-old photographer from Birmingham, England, he, in turn, fell in love with its fluid, accepting, inquisitive version of a religion he thought he was familiar with. “The conversations taking place in these communities are about home, love for those around us, meaning, and, above all, about finding brotherhood and sisterhood,” he explains. Hussain, the son of Pakistani immigrants, grew up in a practicing Muslim household but always questioned if he was devout enough. He says that the Muslims in America project has made him reassess his faith: “I had no idea that making new friends through my work in mosques in American cities would bring me closer to my faith. These beautiful people are teaching me to see Islam in another way. It always felt to me like either you were in or you were out. But the Muslims I am meeting approach their faith as a journey, less focused on right or wrong.”

The fact that most of the men and women in Hussain’s portraits appear attractive isn’t by accident; the photographer uses formal compositions strategically and seductively. “I want people to walk out of a museum or gallery space having seen these faces thinking, Wow, they are gorgeous! That’s enough for me, because it means they are questioning their preconceived ideas of what a Muslim looks like,” he tells me. To this end, Hussain cannily deploys aesthetic devices used in classical portraiture. Whether male or female, young or old, his subjects pose with a preternaturally noble dignity and self-possession that belie the turmoil of their daily lives.

It’s no wonder that a sense of pride emanates naturally from the people in Hussain’s photographs, who are, for once, being seen rather than vilified. Hussain emphasizes the importance of this approach. “These are men and women who appreciate being celebrated rather than patronized or labeled as threatening. My intention is to let them own their identity and experience. If I show them as the vibrant individuals they are, and people walk away in awe, I’ve done my job, because a space for a different conversation is now open.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire,” under the column Viewfinder.