A Portrait of New York in Rocks and Clouds

Mitch Epstein, Clouds #33, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Unlike the frenetic energy of Garry Winogrand, one of his early teachers, the work for which Mitch Epstein is known reflects a contemplative approach to sweeping societal observations. Though he has pursued projects both intimate and far-reaching—Family Business (2004) documents his father’s furniture store and real estate firm and American Power (2009) concerns energy production in the United States—every few years it seems his abiding home of New York City demands his sustained attention.

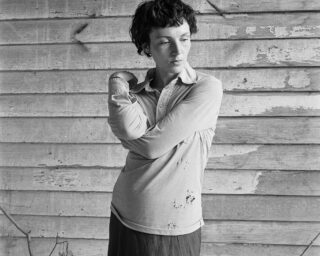

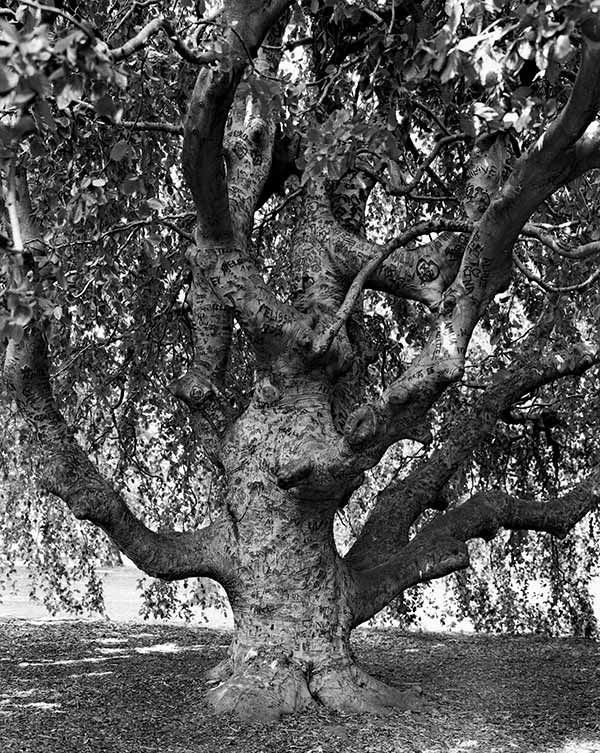

Epstein’s New York Arbor (2011–12) engages his interest in the ways elder trees inhabit the city’s landscape. Shot in large-format, black-and-white film, these trees were witnesses to the city’s development as they grew, gorgeous and ungainly, accommodated by the structures around them. His newest series, Rocks and Clouds (2014–15), currently on view at Yancey Richardson Gallery, can be seen as an extension of this interest: the natural world as it bears witness and participates in the business of New York—the rocks, patiently, for eons; the clouds, for minutes at a time.

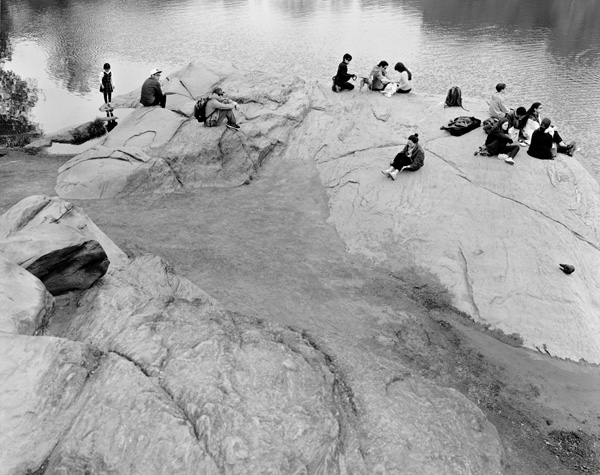

Mitch Epstein, Central Park, New York II, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Joanna Lehan: I was intrigued to read in your artist’s statement that Rocks and Clouds was inspired by both ancient Chinese painters and modern earthwork artists. Which works were you thinking of, and what inspired you about them?

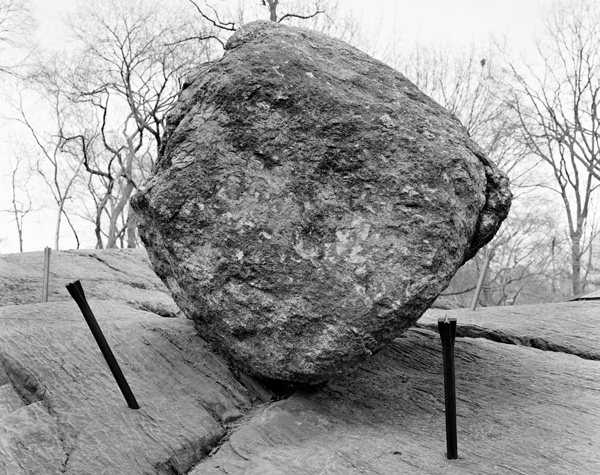

Mitch Epstein: It was Robert Smithson’s essay about Frederick Law Olmsted, “The Dialectical Landscape” (1973), that got me thinking about rocks. Smithson cast Olmsted as the original Earthworks artist and Central Park as avant-garde. Olmsted had moved huge glacial erratic rocks there and uncovered mammoth geological formations, which he used to add a primeval quality to the park’s fields, forests, and ponds.

In Chinese painting and calligraphy, I was interested in the soft horizon, how sky and ground mimic each other and run into each other. Things that are opposite are somehow the same and it’s hard to tell where one stops and the other begins.

The Chinese scholars’ rocks and Isamu Noguchi’s found rocks encouraged me to see the inherent sculptural qualities in found rocks. Carleton Watkins’s wondrous photographs of rock formations in the Western frontier were also inspirational; and Michael Heizer’s enigmatic Levitated Mass (2012) at LACMA reminds me of Olmsted’s park erratics; it’s disorienting and humbling, too.

Mitch Epstein, Clouds #96, New York City, 2015

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Lehan: We’ve spoken before during the production of other work, and I know that you take your time on the research phase and plot carefully where you will make photographs, at least you did with American Power and New York Arbor. How did you research Rocks and Clouds? Is the research portion exciting? Fun? Or is it more something you do dutifully to try to manage the results?

Epstein: I did extensive Internet research on the geological past of the city and where to find visible rock formations. My studio manager, Ryan Spencer, made an iPhone map identifying sites to scout, and I visited several hundred locations looking for rocks, but only photographed a fraction of them. Although I set out in the morning with a clear plan, I often wandered off track and made unexpected discoveries, which was fun! I’m not beholden in my approach to any fixed pictorial idea or typology: my pictures take shape as I compose them on the 8-by-10-inch ground glass.

Mitch Epstein, Rockaway, Queens, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

After six months photographing rocks, I knew the project called for a counterpart. I chose clouds as an opposite to rocks. I thought about ancient time versus contemporary time. Clouds opened up a much broader canvas for the project; they are the most democratic form of nature in the city—they’re accessible. I could photograph them anywhere and in conjunction with anything. I also had a “cloud map” on my iPhone referencing sites that would enable me to photograph clouds in tandem with meaningful elements of the city, be they architectural, human, or natural. The hardest part about clouds was predicting when they’d show up. I had nine weather apps, but none were completely reliable. So research has its limits. A lot of my work is serendipitous.

Mitch Epstein, Indian Prayer Rock, Pelham Bay Park, Bronx, 2015

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

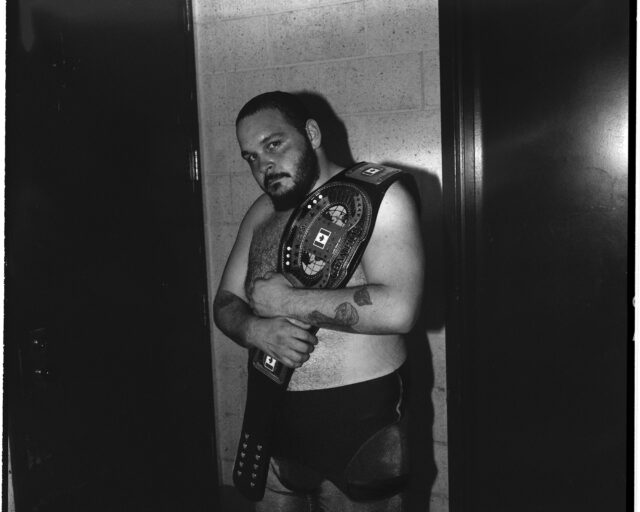

Lehan: A rock, in particular, seems a challenging subject, but your rocks have a dynamic presence. They are monuments and they are—maybe characters?—notably in Central Park, New York II (2015) and Indian Prayer Rock, Pelham Bay Park, Bronx (2015). How did you achieve this? As you were editing your film, how did you know when you got the rock right?

Epstein: How to animate a rock and infer its unfathomable timeline of hundreds of millions of years was daunting. I often returned to photograph rocks multiple times, and there were rocks that I never photographed well. I looked for their kinetic qualities and what distinguished them. Traces of the human hand also mattered; like the Weeping Beech, Brooklyn Botanic Garden (2011) in New York Arbor, the Indian Prayer Rock has many layers of graffiti that have been painted over in a slapdash fashion by Parks Department workers, which give the rock’s surface an odd patina.

Mitch Epstein, Weeping Beech, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 2011

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

I’m a proponent of a slow, introspective approach to photography. I think I avoid clichés by taking time to develop a relationship with my subject—repeat visits help. I consider carefully where to set the camera in relation to my subject, and how focus and depth of field will define and give dimension to my subject. Editing is central to my practice. I never know what my pictures will look like until I see them as contact sheets, and then I study them and work hard at seeing them with detachment and clarity.

Mitch Epstein, Clouds #89, New York City, 2015

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Lehan: But clouds are freighted with photo history, from Stieglitz on. How did you avoid clichés with those?

Epstein: The history of art and photography, and my own past, are crucial reference points; however, I’m not consciously thinking about other photographs or photographers when I’m out in the real world with my camera. Photography, practiced with diligence and an open mind, is capable of transcending the heavy burden of photographic clichés.

My rocks and clouds, like my trees in New York Arbor, exist (photographically) in relation to human enterprise. I’m not a nature photographer. It’s the inextricability of human society and nature that interests me. How do they accommodate and alter one another? For decades, New York City has been a trope for me, a stand-in for all human society. The three series taken together—rocks, clouds, trees—invert a cultural mecca into an elemental city; they flip people’s characteristic self-importance, so that in these photographs, people (and the signs of their hand) are secondary.

Mitch Epstein, Clouds #18, New York City, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Lehan: The work in New York Arbor, and these new works even more so—they seem to represent an evolution in your work, or maybe it’s a distillation. How do you characterize this shift?

Epstein: My evolution has led to a distillation, yes. The formal complexity of my older work, like Family Business and American Power, isn’t gone: it’s set deeper inside the image—there’s a metaphysical layering now, and many of the actual images are deceptively direct. Like certain poems that sound simple but aren’t.

Mitch Epstein, The Hernshead, Central Park, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Lehan: While everything you’ve done shows a masterful ability for sociopolitical observation—these are more existential, more concerned with time. Has this been a conscious movement? Of course that one begs the question—after Rocks and Clouds, what has now captured your imagination?

Epstein: Time is as inescapable in life and as it is in picture making. In the winter of 2014, I ruptured my Achilles tendon and time, as I knew it, came to a halt, which forced me to think about my own human timeline in relation to the long duration of rocks. And later, I considered the speed of clouds—how they come and go so fast.

What I am doing now? Believe it or not, I’m recovering from a calcaneus fracture, only three years after rupturing my Achilles tendon. So who knows where this will lead me. I’m about to go back to a long-term project about the meeting of the animal and human worlds; and I’m also taking on some commissioned work for the first time in many years, and enjoying the challenges of making pictures within the constraints of an assignment, often in unfamiliar territory.

Rocks and Clouds is on view at Yancey Richardson Gallery through October 22, 2016.