Pushing the Boundaries of Gender Performance

Spanning over eighty years of photographs, an exhibition explores the gender non-conforming potential of the word “they.”

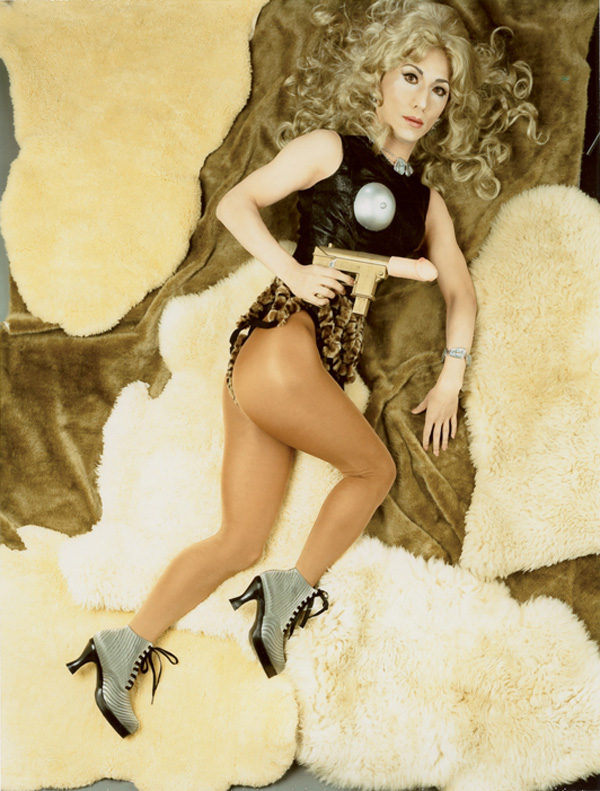

Yasumasa Morimura, Jane Fonda 5 (Barbarella), 1995

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

The singular gender-neutral pronoun “they” was named word of the year in 2016. Judging from the social and historical depth of photography and archival imagery in the exhibition He/She/They, currently on view at ROSEGALLERY, which includes work by more than fifteen artists, it’s crazy to think that it took this long to get American culture at large to recognize life outside the gender binary. Ranging from the early 1930s to the present, the works exhibit a wide array of bodies, locations, gazes, and socioeconomic perspectives, and consider the intersectional influence of race and class on notions of gender.

Lise Sarfati, Malaïka #7, Corner 7th Street and Spring, from the series On Hollywood, 2010

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

Since this exhibition is presented in Los Angeles, Lise Sarfati’s Malaïka #7, Corner 7th Street and Spring from the series On Hollywood (2010), is appropriately local and captures a woman trying to make it in the entertainment industry. In this startling photograph, a young woman appears forlorn, perhaps returning from an audition, unsure of what to do next. The actress’s face, and the low-angle perspective, is reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #21 (1978), in which a young woman, who could be any (white) woman, looks intently beyond the frame, with an imposing block of skyscrapers forming the background. Marrying visual art and Hollywood icons, her dress and hairstyle reference Marilyn Monroe and the “dumb blonde” archetype.

Katsumi Watanabe, KW 164, 1965

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

For her series Carnival Strippers (1972–75), Susan Meiselas captured a type of femininity less visible during the women’s liberation era. One of her primary subjects was Mitzi, a woman who worked as a stripper at carnivals; Meiselas documented Mitzi’s public work and private life. Earning money from a performance of sexuality as dictated by the male gaze, Mitzi capitalizes her body under a patriarchal society. Around the same time, Katsumi Watanabe was photographing Tokyo’s queer nightlife scene, creating vivacious images of drag queens, gangsters, prostitutes, and entertainers in Shinjuku Ni-chome, Japan’s largest gay district. His subjects often commissioned the pictures themselves. The locations—outdoors in front of cars or posing inside scuzzy backrooms—suggest a contrast between the dazzling outfits and the milieu, a queer underworld area of Tokyo. Meanwhile, Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s elegant, perfectly contoured black-and-white portraits offer a singular focus on his subjects’ gender presentations. He pictures individuals like Frida Kahlo, as well as the tuxedo-clad authors Salvador Novo and Xavier Villaurrutia. Their gender presentations are both very masculine, but in the context of this show, they could easily be read as trans men or individuals in male drag.

Nikki S. Lee, The Hip Hop Project (1), 2001

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

Well-known names of ’90s identity politics appear like anthology entries, though they remain relevant today. Yasumasa Morimura creates images of himself in drag as various female celebrities such as Elizabeth Taylor, a critique of both the perceived emasculation of the Asian male body and a global obsession with Hollywood. Nikki S. Lee takes masquerade and cultural identity to another level with her chameleonic (and controversial) self-portrait projects about “passing” in various American subcultures, from hip-hop girls to exotic dancers. In his series Orchard Beach: The Bronx Riviera, Wayne Lawrence portrays glistening beachgoers at the only public beach in the Bronx. Lawrence’s work is among the few representations of African American subjects in the exhibition, but the connection to a critique of gender of this context is unfortunately vague.

Wayne Lawrence, Cathy, Ocean Drive, South Beach, 2010

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

Other works in the show focus less on the performance of gender, and more on people who defy normative gender distinctions. Nineteenth-century photographs depict Native American “two-spirit” individuals—those who participate in gender roles not assigned to their sex—but the accompanying text explains that intersex, androgynous, and gender non-conforming people could be held in high regard outside of Eurocentric, heteronormative cultures. In photographs by Mexican artist Graciela Iturbide, Magnolia, who identified as Muxe (Zapotec for homosexual and “genderqueer”), poses for the camera wearing a dress and sombrero, a traditionally male accessory.

Graciela Iturbide, Carnaval, Tlaxcala, Mexico, 1974

© the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY

He/She/They leans heavily on the visual language of portraiture, which might suggest a desire for authenticity in documentation, in contrast to much of the dynamic content found online, where self-expression by social media sensations, celebrities, and everyday people appears to be constantly evolving. The photographs in this show offer a fixed moment in time, declarative and definitive, but also remain open to the many shades of identity, the gender non-conforming potential of the word “they.”

He/She/They is on view at ROSEGALLERY, Santa Monica, through November 30, 2016.