Brassaï, Lulu at the bar, ca. 1930

© Estate Brassaï – RMN and courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

This article and photographs were originally published in Aperture‘s spring 2015 issue, “Queer,” under the title “Queer Looking.”

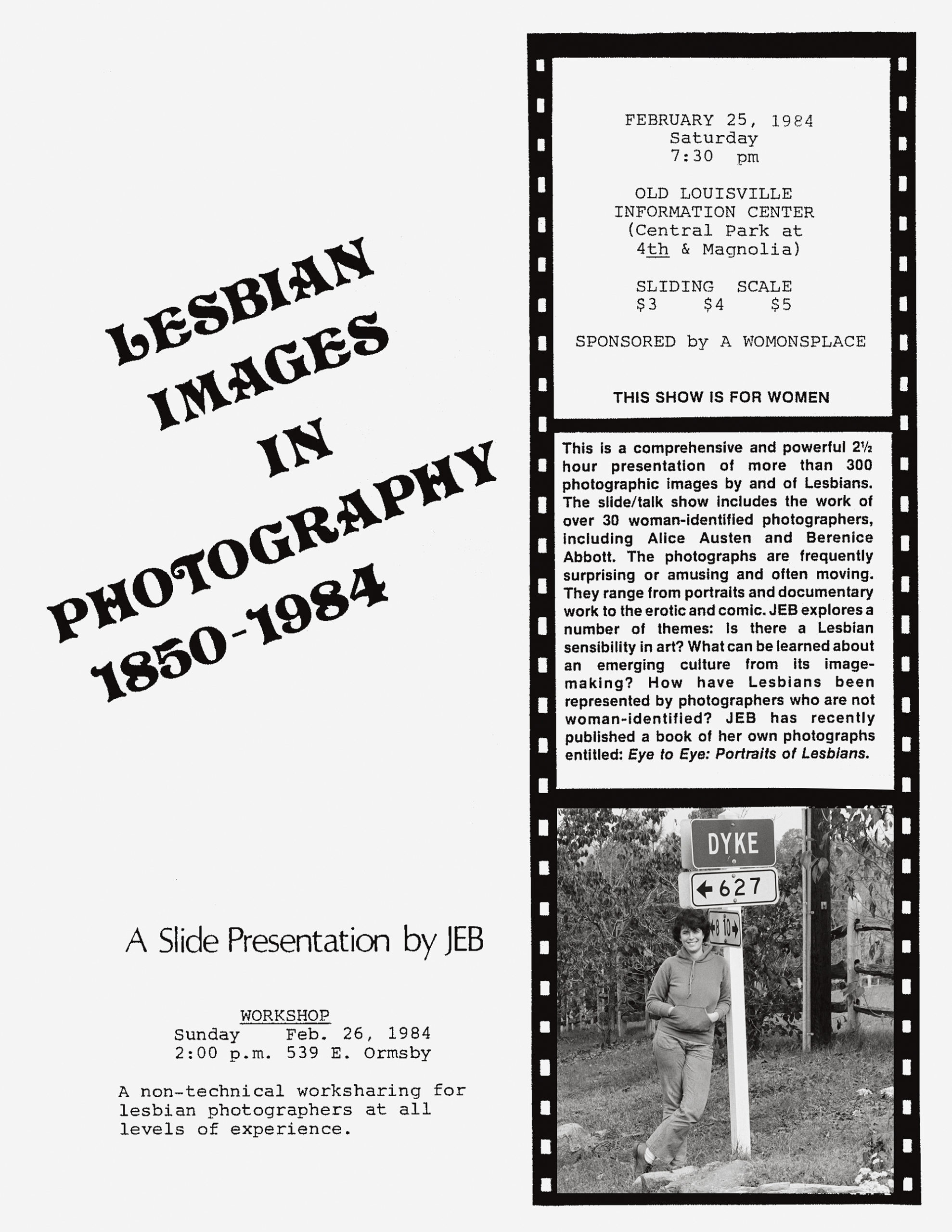

From 1979 to 1985, American photographer and activist Joan E. Biren (JEB) traveled across the United States and Canada delivering an ever-evolving slide show, Lesbian Images in Photography: 1850–the present, more affectionately known as the “Dyke Show.” Over the course of two and a half hours, JEB narrated and presented more than three hundred images to women who gathered in church basements, community centers, women’s bookstores, and coffeehouses, eager for, as Carol Seajay, cofounder of San Francisco’s Old Wives Tales feminist bookstore and publisher of Feminist Bookstore News, put it in an early review, “Images I had never seen before, images I had seen and not perceived. Images on which to build a future.” The slide show was designed to grow over the years, as JEB added new pictures by contemporary photographers and participants in the photography workshops that she led wherever she appeared with the show. It eventually included 420 images. What began as a way to distribute and give context to JEB’s self-published monograph, Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians (1979), became a vocation. She ultimately presented the slide show at least eighty times in more than sixty places.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

JEB structured the Dyke Show in six sections that presented historical photographs by figures such as Lady Clementina Hawarden, Frances Benjamin Johnston, Alice Austen, and Berenice Abbott, alongside a range of contemporary portraits, erotica, and documentary photographs of the early gay liberation movement, her own work, and that of her peers, including Cathy Cade, Tee Corinne, Diana Davies, and Kay Tobin. She laid out for her audiences a new visual history, one with lesbians at its center. In line with lesbian and feminist consciousness-raising sessions of the 1960s and 1970s, JEB used the slide shows as a collective exercise in reading photographs to highlight the paucity of the visual record for lesbians and to impart a new way of looking, a queer way of looking.

She did this in two ways. First, she identified historical photographers who, in her view, rebelled against social norms and narrow expectations for women and, in their work and in their lives, embodied a sense of strength, freedom, autonomy. Hawarden, Johnston, Austen, and Abbott formed the focus here. In a recent email, JEB wrote, “Because relatives and others destroyed the evidence of lesbian lives, and because many photographers had to stay closeted in order to survive or make a living in prior times, there wasn’t a lot of overt evidence. That’s why I felt it was necessary to ‘read between the lines’ of the existing biographies to interpret the images myself given my own experience and instincts.” JEB suggested that there is something in the photographs by these women that can be “read” against biographies that may have suppressed or omitted details about their relationships and sexuality. The photographs supplied a different kind of evidence, discernible perhaps only to those who knew what they were looking for.

Publicity flyer for JEB’s slide presentation, “Lesbian Images in Photography, 1850–1984,” 1984

© 2014 JEB (Joan E. Biren) and courtesy Joan E. Biren Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

Frances Benjamin Johnston’s 1896 cigarette-smoking, beer stein–toting, ankle-revealing self-portrait is a strong case in point: Johnston’s playful self-presentation in this photograph defied the more demure, ladylike norms of her time. Offering information about Johnston’s life as a successful photographer— she is described in the 1974 monograph A Talent for Detail as an “eccentric,” “bohemian” woman who never married—JEB hinted during her slide show that Johnston may have been a lesbian. Though not able to offer clear evidence of Johnston’s sexuality, JEB nonetheless felt that assuming Johnston was heterosexual was equally tenuous.

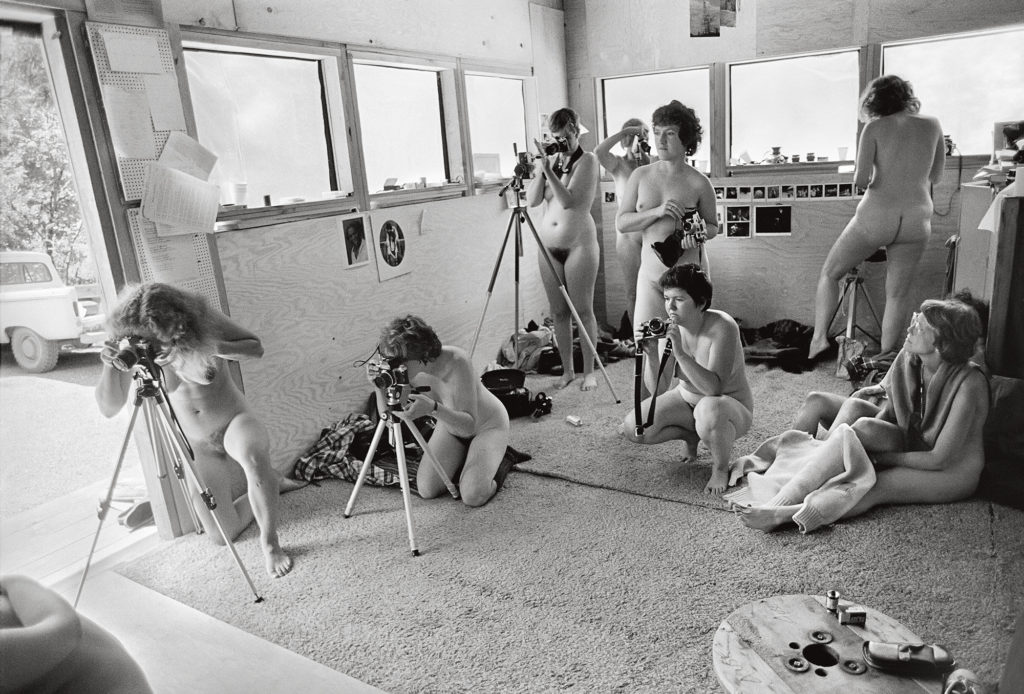

Second, JEB sought to forge what she now describes as a “lesbian semiotics” (though she admits she learned the term much later and was not aware of Hal Fischer’s 1977 book Gay Semiotics). She detailed what she calls the “triangle” of interactions between the photographer, the muse (subject), and the viewer. (She elaborates on this further in her article “Lesbian Photography—Seeing Through Our Own Eyes,” published in Studies in Visual Communication in 1982.) She contrasted photographs made by straight photographers and those made by lesbians. And, in a section called “The Look, the Stance, the Clothes,” JEB attempted to identify more concretely the visual elements that might characterize a lesbian photograph.

© 2014 JEB (Joan E. Biren)

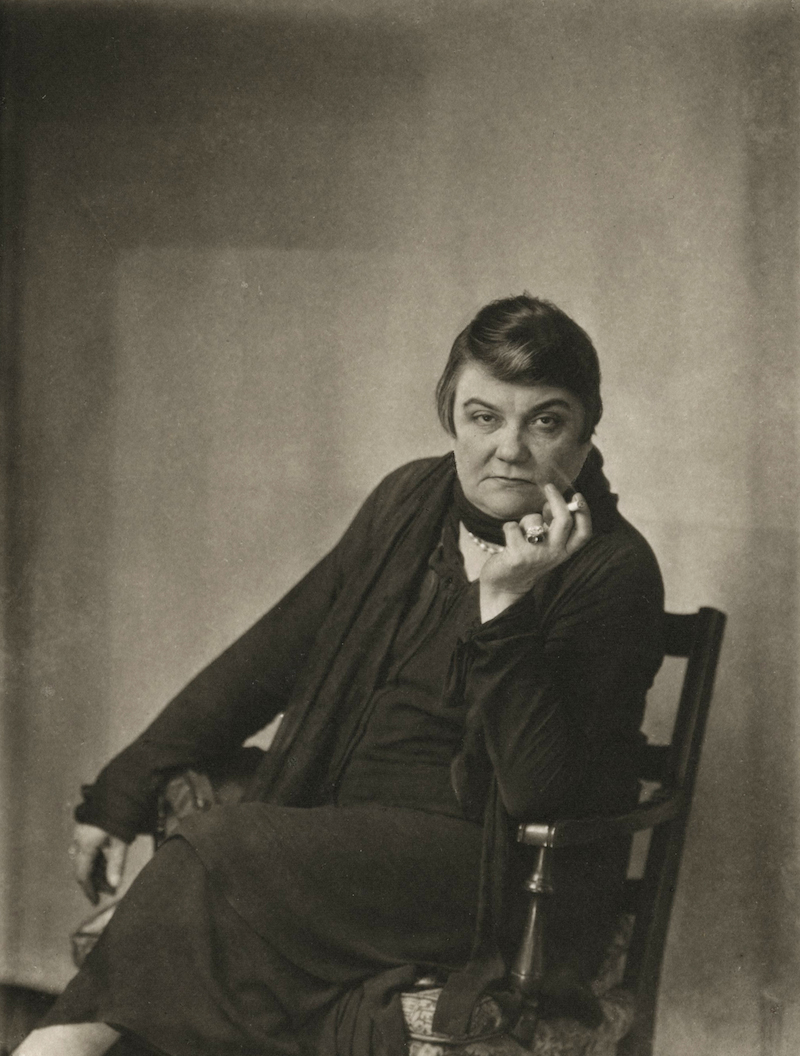

For example, she identified a direct look as the product of a certain rapport between photographer and subject, as in Berenice Abbott’s portraits of Eugene Murat, Jane Heap, or Janet Flanner. “There’s a look here that’s passing between a lesbian muse … and a lesbian photographer, something direct about it, without being confrontative [sic], it’s open in a certain kind of way, there’s a presence there behind the eyes,” she stated during a 1982 slide show at the Women’s Building in San Francisco. JEB found this directness lacking in other portraits of these women, indicating that they didn’t “look as powerful.” Or she characterized certain postures (slouchy) or clothing (pants, creatively fashionable garb) as more lesbian than others. Such a project may feel quaintly essentialist today when queer images are so much easier to find. Audience comment cards reveal that not everyone embraced JEB’s approach even then—some felt she was replacing one set of stereotypes with another. Queer looking was just evolving. However, it is important to note how radical it was to even publicly contemplate a question like Is there a lesbian aesthetic? at the time, as that generation of queers fought for basic civil rights, built communities, and embraced their distinctiveness. JEB proposed a new relationship to photography to her audiences, one that would empower them as creators and interpreters of their own image. “Understanding you have a place in history and in the present day with others like yourself is what gave people the courage to take the risks that coming out in those years demanded,” she explained in a recent email.

JEB’s grassroots campaign is best understood as one of the projects that developed alongside the LGBTQ rights movement from the 1960s on, whose larger aim was greater visibility as a path to greater acceptance: the production of a visual record. In a 2004 interview as part of Smith College’s Voices of Feminism Oral History project, she declared, “I dredged up all these images, which may or may not have been lesbian images. I decided to talk about why I thought they were lesbian images from history. Because this void, this emptiness, this blank of history drove me crazy.”

Building this queer visual history has come about as queers have created images to reflect their own experiences and points of view—they made early and effective use of photographic representations as tools for reflection, self-identification, and activism. But many have also, like JEB, cast back into the image record, pre-Stonewall, to reclaim and reinterpret images made decades earlier. Regardless of original intention and publication context, photographs from snapshots to press prints, by known and unknown photographers, have been used as evidence of queer lives lived or to emphasize queer views of the world.

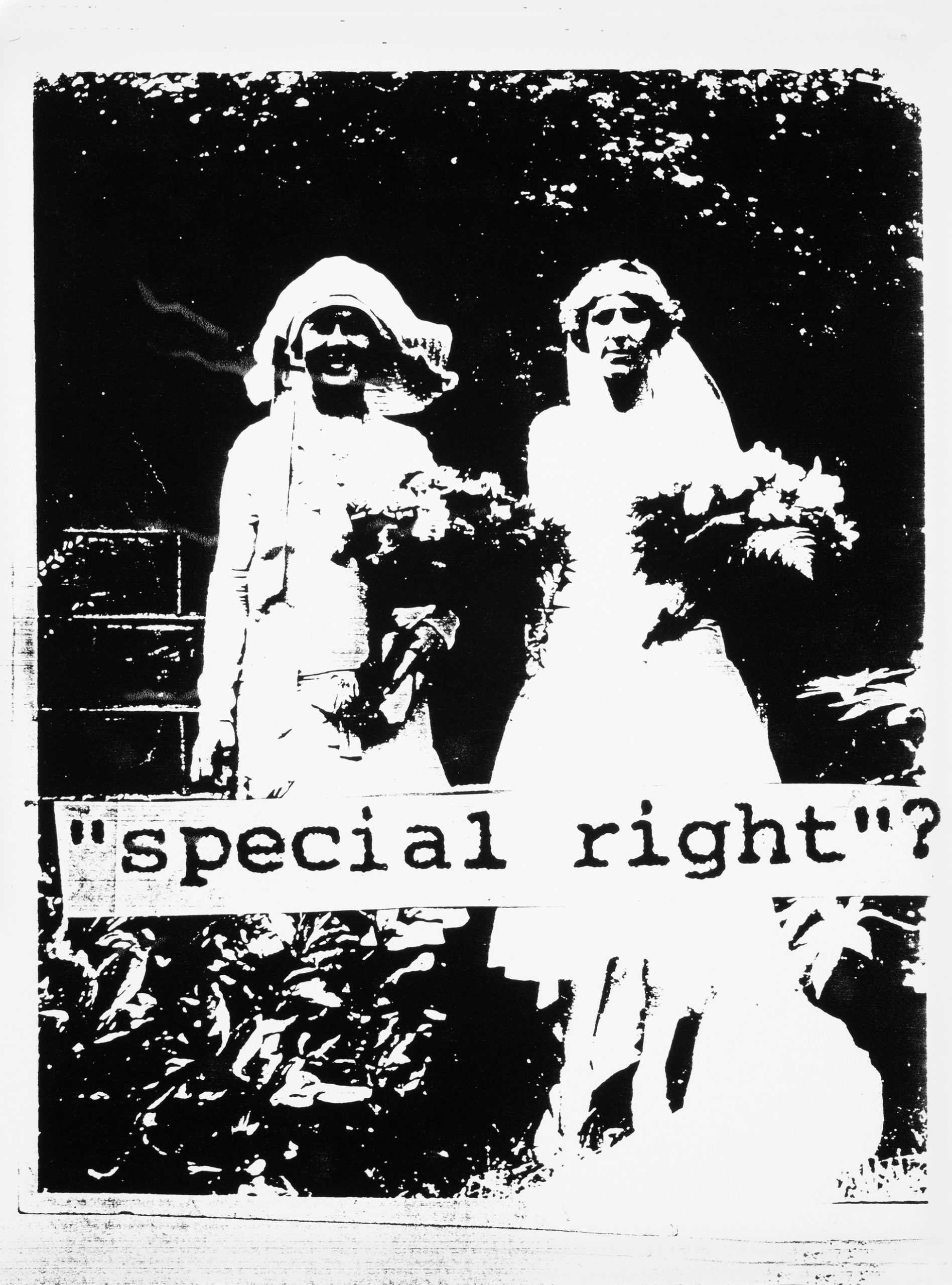

© fierce pussy and courtesy the International Center of Photography (ICP), New York

Courtesy the artists and Special Collections, E.P. Taylor Library & Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Toronto’s monthly gay magazine, The Body Politic, for instance, regularly published such photographs with these ends in mind. Well-known photographers, both queer and not, including Brassaï and Cecil Beaton, as well as images of queer subjects W.H. Auden, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, and Walt Whitman, among others, were pressed into service. A particularly touching example of this reclaiming was published in The Body Politic’s March/April 1972 issue in which writer Ed Jackson penned a tribute to a deceased relative, Harriet Huestis Jackson, whom he had only encountered through a tintype in his family’s archive. Her evident facial hair led him to describe her as “one of the early but solitary fighters in the sexual revolution, an unsung heroine who dared to demonstrate for posterity the relative unimportance to sexual identity of a patch of hair.” The title of Jackson’s homage—“From the Family Album”—highlights not only the source of his astonishing find but also the impulse for creating and maintaining such an album, be it of biological or chosen family.

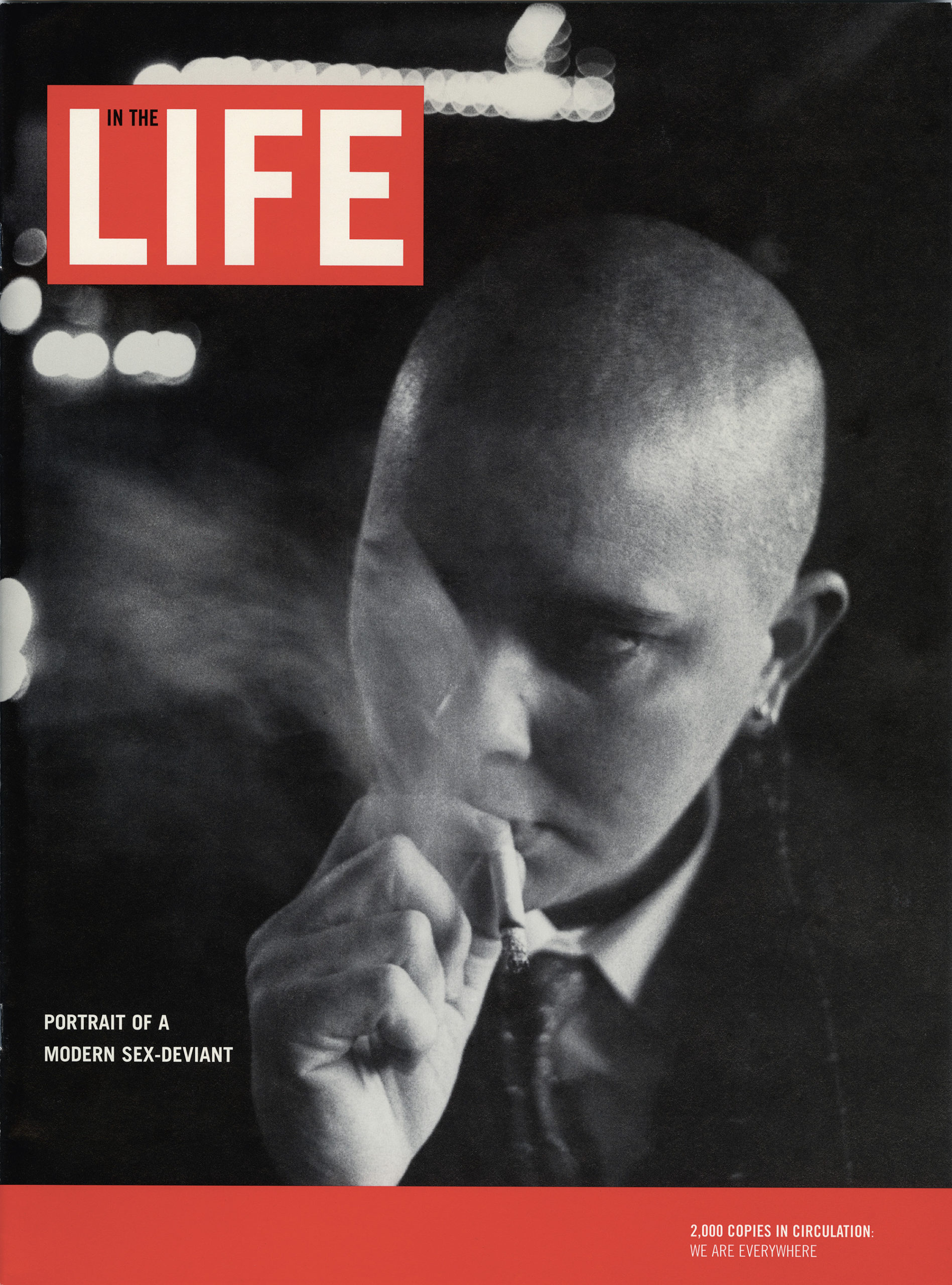

This queer interpretation of photographs from the past continues. Artists like Canadian Nina Levitt, who recast Alice Austen’s well-known group photograph The Darned Club in her 1991 work Submerged (for Alice Austen), or the American collective fierce pussy, who in the early 1990s created Xerox posters from their own baby pictures, class portraits, and other family snapshots, pushed this queer approach into more mainstream contexts—the art gallery and street, respectively— drawing attention to overlooked gestures and challenging unexamined assumptions. Canadian duo Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan took this one step further, inhabiting the format of Life magazine, mimicking its earnest perspective to both highlight and gently skewer lesbian stereotypes. More recently, critic and curator Vince Aletti created a wall installation at the Art Gallery of Ontario from photographs, newspaper clippings, magazine pages, exhibition invites, and other ephemera from his collection, making an analog cloud that was testament to decades of queer looking.

© Berenice Abbott/Commerce Graphics/Getty Images and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Though Aletti’s collecting impulse originates from more private, personal interests, as opposed to JEB’s more public, political ones, they nonetheless spring from a common sense that these images stand for more together than alone and that the act of looking shapes us. Perhaps more importantly, they share a sense that this act is one of pleasure. Audio from JEB’s 1982 slide show at the Women’s Building reveals an audience whose reactions ranged from playful raucousness to quiet outrage to knowing laughter, as they responded to the images and the narration. One writer who saw the slide show in Toronto wrote a review for The Body Politic, where she expressed her delight with and her hunger for these images: “It could have continued for hours more and still I would not have been satiated.” Beyond this immediate experience, the reviewer felt her life and desires had been affirmed in a lasting way: “Separately these images are only fragments; put together they form a history that becomes a reality….It has given us a past, shown us a present, and even hinted at a future.”

The future occupies JEB these days as she now actively builds and cares for queer visual records and archives. She is organizing her slides and negatives, preparing to deposit them at the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, where they will join her papers. Always attuned to the big picture, JEB is also mentoring her lesbian contemporaries on how to preserve and find repositories for records of their own lives, as well as advising institutions like the Archives Center at the National Museum of American History on how to increase their holdings of queer material. She states simply, “This is the continuing work of making sure we will never be invisible again.”