These Queer PhotoBooks Changed My Life

Eleven curators, writers, and artists reflect on images of queer identity past and present.

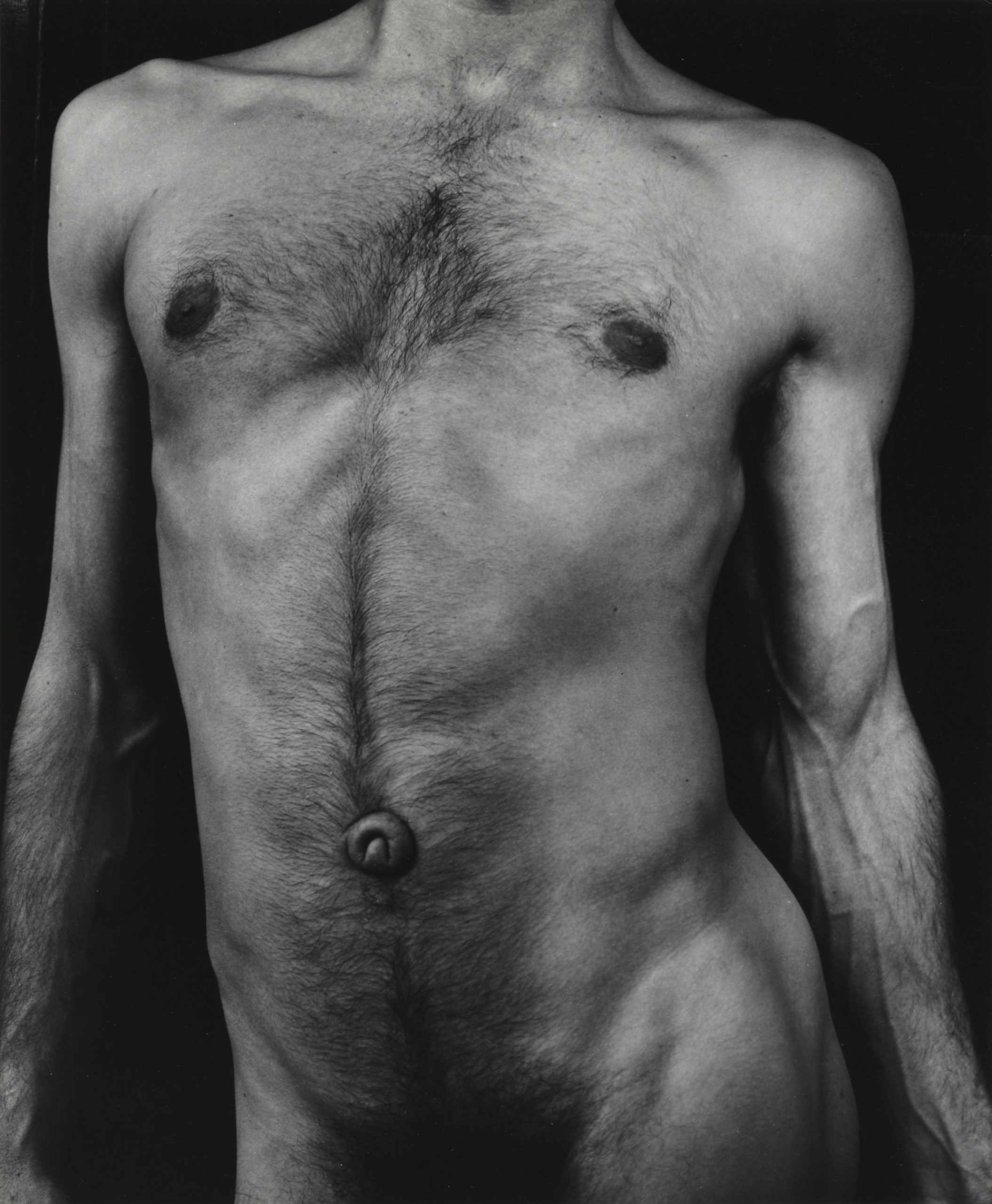

Minor White, Shore Acres State Park, Oregon, 1959, from the book Minor White: The Eye that Shapes (Princeton University Art Museum in association with Bulfinch Press, 1989)

In honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, we asked some of our favorite queer photographers, writers, and historians to choose a photobook that was important to their development as artists and human beings. Ranging from the early days of photography to the present, these books perform an intimate yet consummately public function: they wait on the shelves of libraries and bookstores to let people know that they are not alone, that queers do have a history, that someone cared enough to write it down. —Brendan Embser and Matthew Leifheit

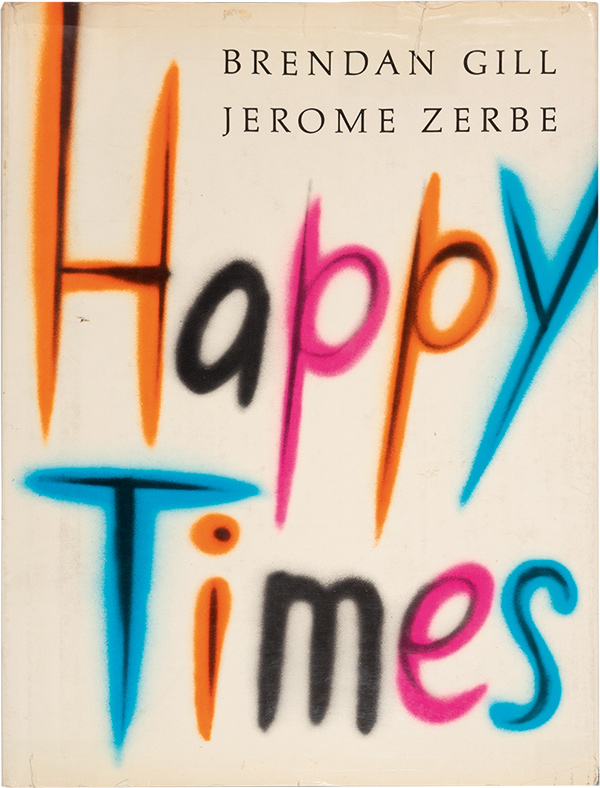

Timothy Young on Jerome Zerbe and Brendan Gill, Happy Times, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1973

Happy Times, with its gaily painted cover, is a survey of the work and social world of paparazzo Jerome Zerbe, though it is more than a compendium of celebrities and socialites. With focused looking, images delaminate and reveal kinships: Marlene Dietrich dancing with Clifton Webb, Cary Grant, Lili Damita’s smile, Zerbes’s boyfriend Lucius Beebe, Cole Porter, Katharine Hepburn with her picnic basket, Hermione Gingold doing the Twist, Steve Reeves in the shower, Salvador Dalí with Amanda Lear . . . Maybe history is indeed a big, queer conspiracy—and Zerbe was there to capture it in joyous bursts of light.

Timothy Young is curator, modern books and manuscripts, at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

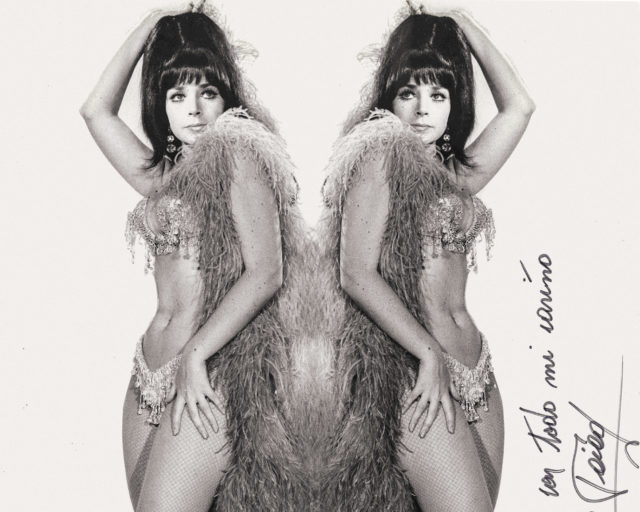

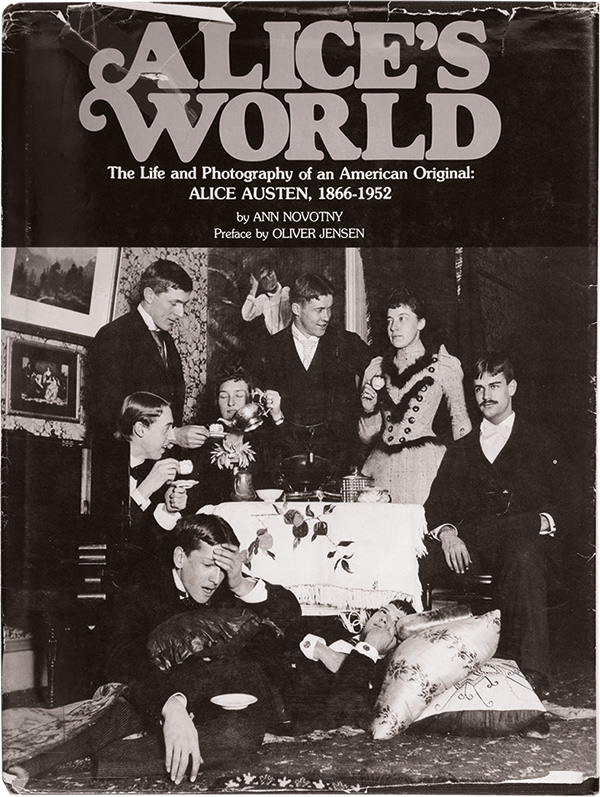

Joan E. Biren on Ann Novotny, Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original; Alice Austen, 1866–1952, Chatham Press, Old Greenwich, Connecticut, 1976

Alice’s World: The Life and Photography of an American Original by Ann Novotny (now out of print) is a biography with images from an early documentary photographer who worked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Alice Austen’s photographs of her friends were the first images I ever saw of women that I identified as authentic lesbians, that is, not photographs of women together made by men and for men. Alice’s photos are funny and sexy and when I found them, I felt that I was discovering a true ancestor. Ann Novotny’s book was my 23andMe—only better than genetic testing.

Joan E. Biren (JEB) is a photographer and filmmaker.

Courtesy the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Philip Gefter on Duane Michals, Homage to Cavafy: Ten Poems by Constantine Cavafy, Ten Photographs by Duane Michals, Addison House, Danbury, New Hampshire, 1978

When it was first published, in 1978, this book introduced me to the work of Cavafy, a significant Egyptian/Greek poet of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Duane Michals’s photographs-with-text are single narrative images that assert the conditions of inhibited homosexual desire with lyricism, joy, and melancholy, echoing the feeling and attitude of the poems. It is an artistic tribute to the poet by a serious kindred artist—from one artist to another, from one generation to another.

Philip Gefter is the author of Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe; A Biography (2014).

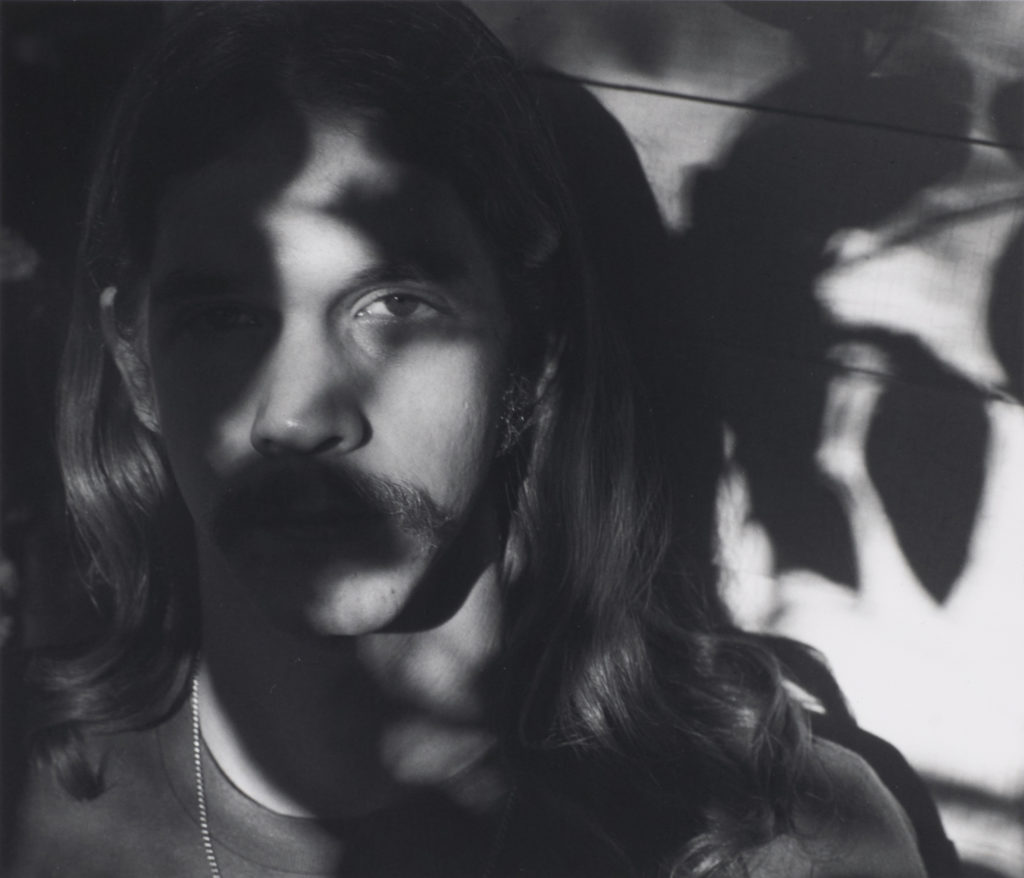

David Benjamin Sherry on Minor White, Rites & Passages, Aperture, New York, 1978

Traversing America as a queer person, camera in hand, in search of meaning and metaphor in our troubled landscape has a certain weight to bear. The road is lonely to begin with; add the juxtaposition of an outsider looking in and trying to navigate the suburban, rural, national park, state park, and campground cultures, all quintessentially heteronormative—it could be said the experience of seeing is heightened, the isolation stronger, the connections between nature more dramatic, and maybe the desire to be loved or to connect with others even more intense, because you’re constantly made aware of your otherness. I’ve often found the strength to pursue this line of work from the varied books of American photographers that line my shelves, though few queer ones come to mind, with the exception of Minor White and specifically his Rites & Passages. White’s work has been an endless road map of encouragement, power, and comfort on some of my darkest nights while alone on the road. His own wandering through the terrain has resulted in a book of countless photographic gifts, each leading to the next: earthly matter, abstract synapses in the universe (or maybe ice forming on a windowpane?), blazing landscapes, erotic portraiture, empathetic abstractions. He creates a mindscape that glimmers with spiritual epiphany, a multitude of cerebral queer experiences that continually awakened him. His work is proof to me that magic is real in the world; queerness is power and the camera can be a tool used to harness the energy.

David Benjamin Sherry is a photographer based in Los Angeles.

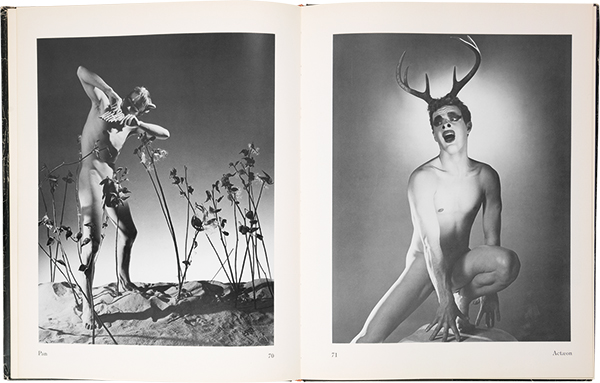

Jonathan D. Katz on Jack Woody, George Platt Lynes: Photographs 1931–1955, Twelvetrees Press Pasadena, California, 1981

My all-time favorite queer photobook has to be Jack Woody’s George Platt Lynes: Photographs 1931–1955. It was 1981, the year that Reagan was first elected and the Christian Right began its horrifying ascent. Fairly newly out, I didn’t know Lynes then, but as I leafed through the book on the newly published table at the local queer bookstore, I was transported by a long-dead, preciously gay artist who seemed to me every bit as politicized as I yearned to be. The way the photographs instrumentalized the gaze—and I was just discovering the pleasures of a stare held a beat too long—and the unabashed eroticism were delicious, of course, but so too was Lynes’s evident attention to the power of another kind of gaze to engender feelings of shame, loss, or insecurity.

No matter how explicitly the body was figured in Lynes’s work, it was the question of sight, of being seen or not wanting to be seen, of holding or ducking a look that struck me. Lynes’s work spoke to me because it gave both form and precedent to that dynamic circuitry then investing the newly spectacularized queer body with a host of cruelly competing meanings.

Jonathan D. Katz, an art historian and curator specializing in queer visual culture, chairs the doctoral program in visual studies at the University at Buffalo, New York, and is a visiting professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Shannon Ebner on Peter C. Bunnell, Minor White: The Eye that Shapes, Art Museum, Princeton University in association with Bulfinch Press, Princeton, New Jersey, and Boston/Toronto/London, 1989

This catalogue was published on the occasion of Minor White’s Museum of Modern Art retrospective in 1989, my senior year of high school. As a teenager living in close proximity to the city, I would board the 11A bus to Port Authority from downtown Hillsdale, New Jersey, and visit the museum as often as possible. White’s exhibition was the first photography retrospective I had ever visited, and one of two museum catalogues I somehow managed to purchase as a teenager. But more than that, upon returning home to the privacy of my suburban bedroom, it was where I discovered in a book the name for what had stirred me: homoeroticism, as the catalogue author, Peter Bunnell, calls it. White’s photographs of nude male bodies were obvious, even if shocking, to my eyes, but it was the landscapes—rocks protruding from glistening sandy shores in formations resembling torsos and glory holes, full of transferred desire—that were the revelation. Here was a celebration of homosexuality—what an old-fashioned word, but somehow fitting for White’s expression of gay, white-male modernist sexuality, newly discovered to me and never to be forgotten.

Shannon Ebner is an artist and the chair of Pratt Institute’s photography department.

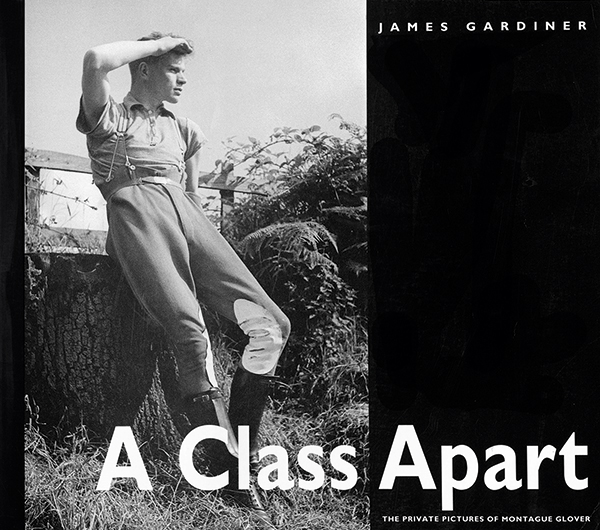

Deborah Bright on James Gardiner, A Class Apart: The Private Pictures of Montague Glover, Serpent’s Tail, London, 1992

Two cardboard boxes of “dusty negatives and faded letters” from an estate sale fell into the hands of James Gardiner, a collector of gay photographs and ephemera. The resulting compilation, A Class Apart, is a rare (and sexy!) look at homoerotic cruising in London a century ago through the photographs of architect and amateur photographer Monty Glover. Most poignantly, Glover documented his fifty-year love affair with Ralph Hall, the handsome working-class lad who became his muse.

Deborah Bright is an artist and writer based in Brooklyn.

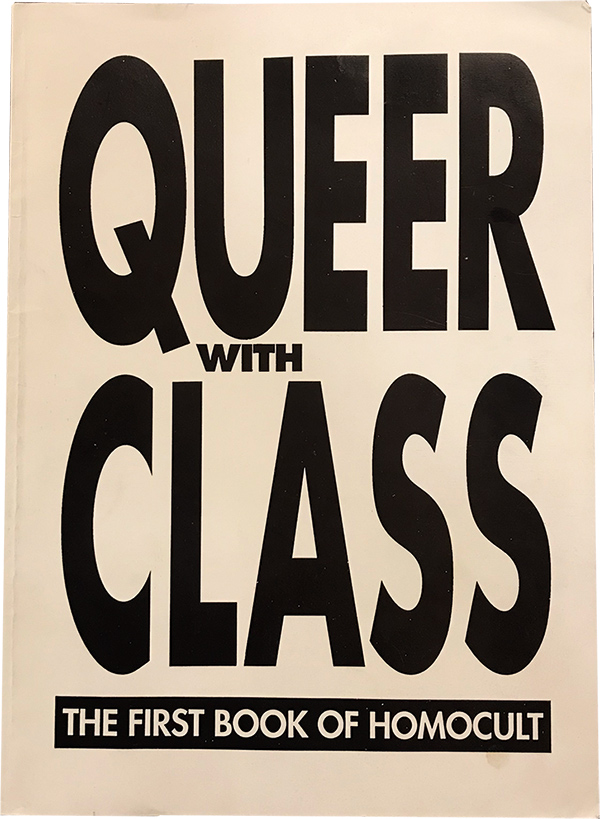

Laura Guy on Queer with Class: The First Book of Homocult, MS ED (The Talking Lesbian) Promotions, Manchester, UK, 1992

Homocult, self-proclaimed “perverters of culture,” were a Manchester-based collective comprised of working-class queers who were active in the early 1990s. Their printed graphics and graffiti actions, featuring slogans like “Give us your children / what we can’t fuck we eat,” railed against the moral certitude of the political right and continue to offer antidote to the assimilationist agenda of a mainstream LGBT movement. Queer with Class: The First Book of Homocult compiles many of Homocult’s posters into a thin paperback volume. Significantly, as with the broader DIY zine culture to which the book belongs, photography is not a rarefied form here but is put to the work that it does best. Images are lifted from elsewhere, glued alongside text, and blown up on Xerox machines. As the illegitimate offspring of mechanical reproduction, Homocult eviscerate the breeding ground of capital: the heterosexual family. Punk to the end, the first book of Homocult was also the last.

Laura Guy is an Early Career Academic Fellow in Art History at Newcastle University, UK.

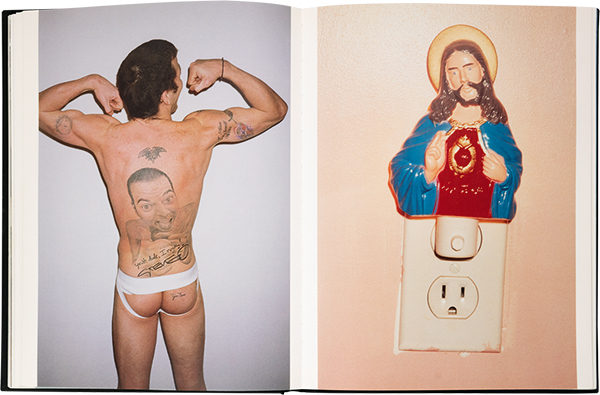

Kayode Ojo on Terry Richardson, Terryworld, Taschen, Cologne, 2004

When I was a student, the only copy of Terryworld had been stolen from SVA’s library stacks. I thought it must be highly coveted, so I was pleased to find a copy for a reasonable price on Amazon.com. When my copy arrived, I noticed some of the pages were stuck together. I’m not sure why I assumed this was because of a man.

In New York, people complain to me about Terry Richardson and his abuse of power because we use the same camera; I’ve brought the camera into the bedroom on a few occasions and exhibited the results. I ask them, if I meet someone cute at a party, is it bad for me to ask them to come back to my apartment to take some pictures? It’s a real conversation-ender.

These days I’m wondering which luxury fashion brands I need to shoot for in order for people to do things for me that they don’t really want to do. Is it Brioni? Missoni? Fiorucci? Was it Gucci? Does sex still sell? Is domination still Gucci?

Anyway, this book contains a lot of pictures of men.

Kayode Ojo is an artist based in New York City.

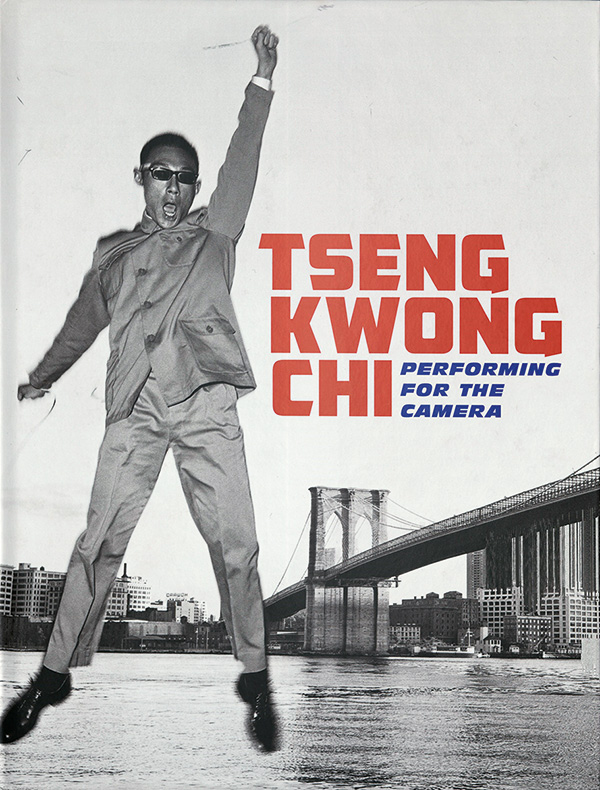

Ka-Man Tse on Tseng Kwong Chi, Performing for the Camera, Chrysler Museum of Art, Grey Art Gallery, and Lyon Artbooks, Norfolk, Virginia; New York; and Brooklyn, 2015

My favorite books are the kind you can slip into your winter coat pocket: Langston Hughes and Roy DeCarava’s Sweet Flypaper of Life, or James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, or any Maggie Nelson book. My favorite queer photography books are the kind I can’t carry around or hold easily with one hand while standing on a subway . . . blame it on its being a little too cumbersome—or is it that it would make me blush, red and ears burning (such as Peter Hujar’s Love and Lust)? One that I would say is just as smoldering, beautiful, wild, disruptive, timeless, and urgent—and that I would want to lug around all day, and to pass on, like a lighter—is Tseng Kwong Chi’s posthumous exhibition catalogue Performing for the Camera. It hits many registers: wit and humor, subversion, performance, infiltration, critique. What does resistance look like for a queer Asian American artist working in the late 1970s and 1980s, who was perceived as a perpetual foreigner? There is an insistence on being present, on being both visible and invisible. In the work, you feel his defiant, fiercely intelligent exuberance.

Published in 2015 and as the first comprehensive survey of Tseng Kwong Chi’s work, the book only reminds me of his absence, and all of the occlusions and acts of recuperation, in the canon, the curriculum, and the archive—the epistemic violence, the quiet violence of invisibility. Who writes history? What does a book, if late or overdue, tell us about ourselves, our will to know, and our unknowns?

Ka-Man Tse, a photographer and video artist based in New York, is the winner of the 2018 Aperture Portfolio Prize.

Courtesy ClampArt, New York

Horace D. Ballard on Frances F. Denny, Let Virtue Be Your Guide, Radius Books, Santa Fe, 2016

I saw the first prints of what would become Let Virtue Be Your Guide in the autumn of 2013. Amid the dying evening light and the white walls, Frances F. Denny’s photographs of family members, domestic interiors, and cultivated landscapes were luminescent in their skillful framing of light, in their unflinching examination of access and class, and their ability to unravel the. distinctions between portraiture and still life. In photobook format, Denny has invited us into her family. In so doing, she offers up an intricate and visceral sense of “home” in a post-archival age.

Horace D. Ballard is curator of American art and research curator for photography at Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.