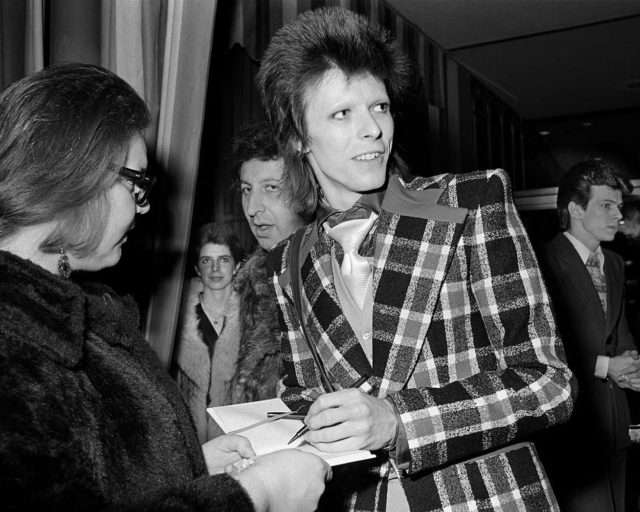

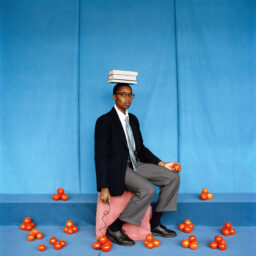

Larry Fink, ICP, Peter Beard Opening, New York City, November 1977

Larry Fink, who passed away at the age of eighty-two on November 25, 2023, was a man of contradictions in the best possible way; he contained multitudes. He was as much an artist and a seer, as a teacher and mentor, a musician, a farmer, Martha Posner’s husband, among many other lives. His work is in the top museum collections, yet he regularly entered the annual juried show for Pennsylvania photographers at the Allentown Art Museum. He was game to be part of the mix. The contrasts suited him. He moved easily between the formal society galas and gatherings of Manhattan’s social elite and the farm life of the Sabatine family, his neighbors in Martins Creek, Pennsylvania. The body of work combining the two, Social Graces, was first published by Aperture in 1984 in an unassuming nine-by-ten-and-a-quarter-inch hardcover for $25. It was his first book, and in the short text—the sole accompaniment to sixty-nine pictures—he mused, “When I walk around in a tuxedo and tap my toes, I’m a fancy dude. When I walk around Martins Creek, I’m a rolling country belly.” Social Graces would go on to become an icon among photobooks and the work that most defined him.

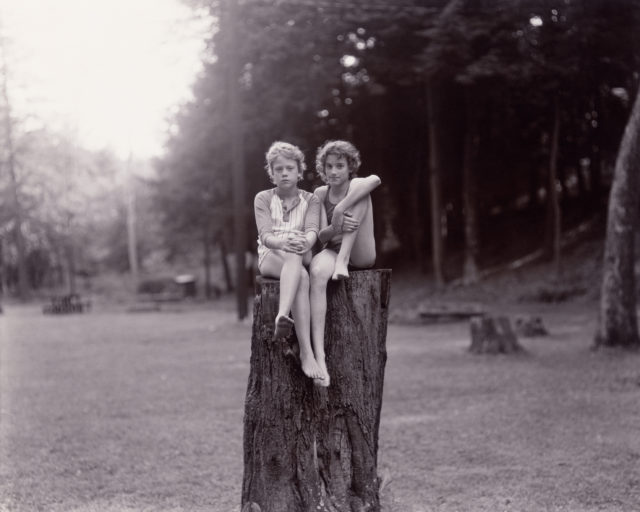

Looking at it again now, in the week after his passing, I’m struck by the gorgeousness of these pictures. All of the things that make a Larry Fink photograph are here: that framing with its push and pull at the edges and vigorous cropping, the flash illuminating and exaggerating the energy, emotion, and sensuality. There’s a real roundness to the printing (produced at the legendary Meriden Gravure) and the physicality that pervades every one of Fink’s pictures comes forward—every wrinkled hand grasping, pursed-lipped smile, rolling country belly. The book begins each sequence in the middle of the party—Peter Beard’s ICP opening and Pat Sabatine’s eighth birthday (both 1977)—and then moves around the edges of the merriment with searing precision. It’s easy to get drawn in. Each picture is captioned simply with the event and year, even the family photos of birthdays and graduations. You can’t escape the truth that the camera stopped time to mark this moment, or the sense of what’s to come when the party’s over or when John and Jeannie Sabatine, already getting on in years in the pictures, pass away. Larry’s daughter, Molly, also appears in the sequence with the Sabatines, as a baby and then a toddler—a visual reminder that time is passing in a personal way for the photographer as well. It’s not that he is thinking of the idea of memory or death, so often touted in relationship to photography. It’s that he’s seeing they’re alive and that photography’s ability to capture this life is miraculous.

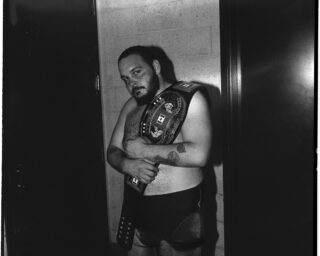

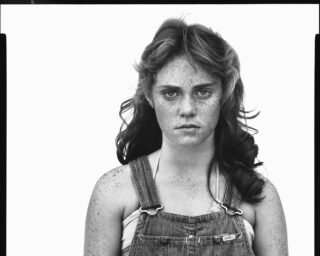

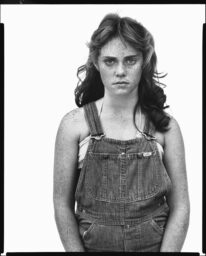

All photographs from Larry Fink on Composition and Improvisation (Aperture, 2014). Courtesy the artist

We worked together on his book for Aperture’s workshop series (Larry Fink on Composition and Improvisation, 2014), which is based on interviews and audio of his insights and teachings. Each visit, Larry would pick me and former colleague Robyn Taylor up from the bus station and drive us to the farm, crossing over the creek and up the winding driveway. And then he would promptly disappear. Where was Larry? He was out talking to a neighbor about a bulldozer or goofing off or in the sauna on the property. When we finally did get to work that first day, we had a magical conversation, talking about the impossibility of using the cold instrument of the camera to convey emotion. But, just as we were both starting to congratulate ourselves on such sparkling, high-minded prose, we realized we had forgotten to hit record. We spent the rest of our time trying to recreate that conversation. It was impossible, but led to other turns and tangents. How good pictures unfold as a question, how the edges of the frame can both enclose and leave open the picture, how to take a picture of water in a way that feels wet or cold, how you had to have a life outside the camera to make meaningful work.

In his singular and elliptical voice, “The goal, I suspect, through harmonies and edges and everything that we have in our command, is to take a dumb two-dimensional picture and make it something that a viewer enters and doesn’t want to leave.” The same could be said about a good book. When a book has been a pleasure to work on, I find myself reluctant to finish it. Even though it is the beginning of the book’s life in the world when it goes to the printer, the process of making it comes to a close. On the workshop book, we were beyond late, and Larry was nowhere to be found when I called the farm to push him again to get through the final layouts. I left a message saying I would give him a prize if he could return it within forty-eight hours—an impossible deadline, but it worked! I wasn’t ready to let the book go then, and I’m not ready to say goodbye now. But I know what Larry would say. We ended the workshop book with: “Photography is not all that there is. You gotta live.”