Kwame Brathwaite, Self-portrait, African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS), Harlem, ca. 1964

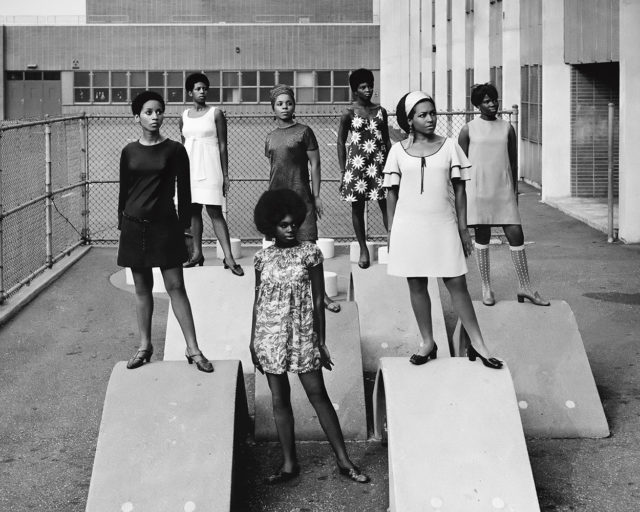

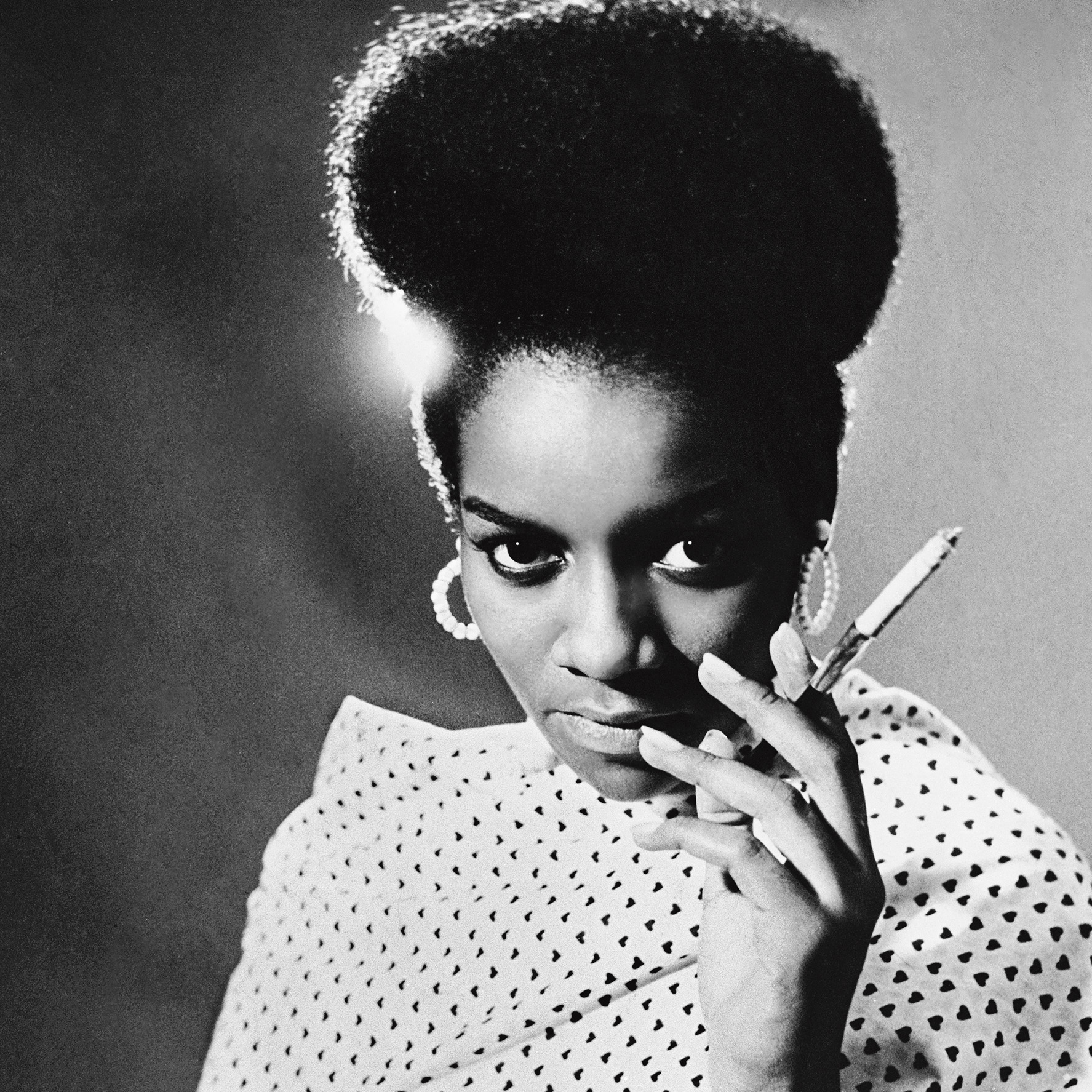

Aperture is deeply saddened by the loss of Kwame Brathwaite, who passed away on April 1, 2023, at the age of eighty-five. Brathwaite (1938–2023) was a visionary Harlem-based photographer who used his images to advance the Black Is Beautiful message throughout the 1960s. From his photographs of jazz icons to his indelible images featuring the Grandassa Models, Brathwaite blended art, music, fashion, and community activism to spread a powerful message of social, economic, and representational justice.

At Aperture, we were honored to feature Brathwaite’s work in the pages of our magazine, to publish his first monograph (Black Is Beautiful, 2019), and to collaborate with him and his son, Kwame S. Brathwaite, to organize a traveling exhibition dedicated to his work. As we consider Kwame Brathwaite’s incredible legacy and how his work continues to move audiences globally, we asked a group of Aperture contributors to offer their reflections.

Antwaun Sargent

Kwame Brathwaite’s influence on the world of Black image production has been felt across the culture. Brathwaite gave visual power to the now common belief that Black is beautiful. This has resulted in generations of Black image makers making photographs that have further defined and celebrated our collective humanity. Without Brathwaite’s considerable contribution I don’t know where photography would be today. His rich image archive is a testament to a people who took control of their own representations.

Antwaun Sargent is author of The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion (Aperture, 2019) and Young, Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists (2020).

Tanisha C. Ford

Much has been said about the power and boldness of Kwame Brathwaite’s photography. It is true, he chronicled the Black radical spirit of the 1950s and 1960s in ways unparalleled. But his sensitivity was his greatest asset. The way he adjusted the aperture of his lens, the way he positioned himself in relation to his subjects: these artistic choices gave his photographs complexity, layers. You can see softness and vulnerability, not just righteous anger, in the facial expressions of the freedom fighters whom Brathwaite captured on celluloid. And you can’t help but to linger in this nuance, to grapple with how the images force you to reconsider everything you think you know about Black Power, about beautiful Blackness. Sensitivity. I immediately discerned the depth and dimensionality of Kwame Brathwaite’s emotional register when I interviewed him for the first time. His sincerity, his humility, informed his commitment to depicting the full humanity of Black people around the globe. I hope we will always recognize his sensitivity as the vital element of his artistic and political legacy.

Tanisha C. Ford is a regular contributor to Aperture, and author of Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (Aperture, 2019), and Dressed in Dreams: A Black Girl’s Love Letter to the Power of Fashion (2019).

Tyler Mitchell

From the moment I first saw Kwame Brathwaite’s work I was transfixed. There’s a clarity and power to his portraits, which remind me that conversations around photography, representation, and equity have always been and will always be vital. I’m saddened to hear of his loss. I thank him for his timeless images and I thank his son Kwame Jr. for his commitment to the upkeep of his father’s archive.

Tyler Mitchell is a photographer based in New York. His work appeared in Aperture’s Winter 2020 issue, “Utopia,” and his book I Can Make You Feel Good was published in 2020.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Ekow Eshun

Kwame Brathwaite said his goal was to show “the greatness of our people” and that’s what he did with his work. He understood that for Black people in the 1960s, a commitment to style and elegance and self-fashioning was not a superficial preoccupation. That’s why the slogan he popularized, “Black Is Beautiful,” was so resonant. It represented a personal politics of visibility and assertion. It was about resisting the white gaze and defining how you were seen on your own terms. It meant liberation. Black aliveness. This is what his photographs stand for.

Ekow Eshun is a curator, writer, and regular contributor to Aperture. His latest book is In the Black Fantastic (2022).