Hilla Becher (1934–2015)

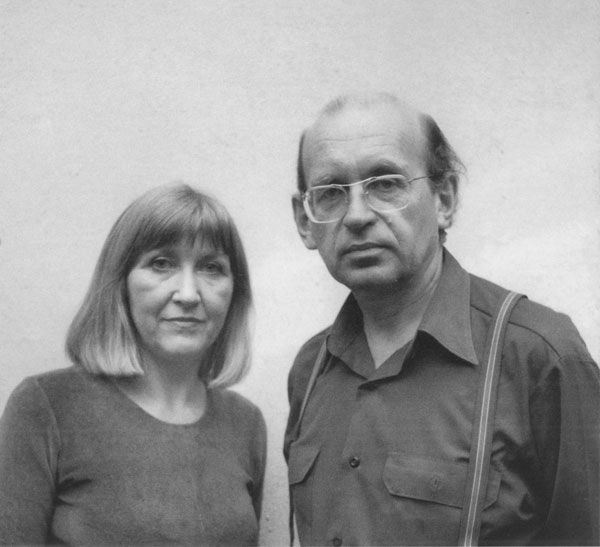

Portrait of Bernd and Hilla Becher, 1985. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery

When Hilla Becher appeared on stage at the Paris Photo Platform in 2012, the event was something like a coronation. With her silver-bobbed hair and infectious intelligence, she deftly answered questions in precise English, and left to a standing ovation. The public lecture accompanied two exhibitions of work that she and her husband Bernd Becher, who died in 2007, had produced over the past half-century. Her rare public appearance and the twin exhibitions were a reminder of the extraordinary public regard for the Bechers and of their broad impact on postwar art and photography. For this reason, the death on October 10, 2015 of Hilla Becher at age 81 felt not only like a profound loss but also like an abrupt end to a unique way of seeing the world.

Hilla Wobeser was born in 1934 in Potsdam, in what was later East Germany. From the beginning, she was immersed in photography. Her mother was a photographer, as was her uncle, who left a young Hilla his darkroom. After moving to Berlin, Hilla enrolled at Lette-Verein, the technical design school where her mother had also studied. By then she was skilled in operating heavy glass-plate cameras, and in 1951 she secured an apprenticeship with the conservative Berlin photographer Walter Eichgrun. Later, while working in advertising photography in Düsseldorf in 1957, Hilla met Bernd Becher, who was then a student at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. The following year, Hilla also enrolled in the Kunstakademie and they began working together. They married in 1961.

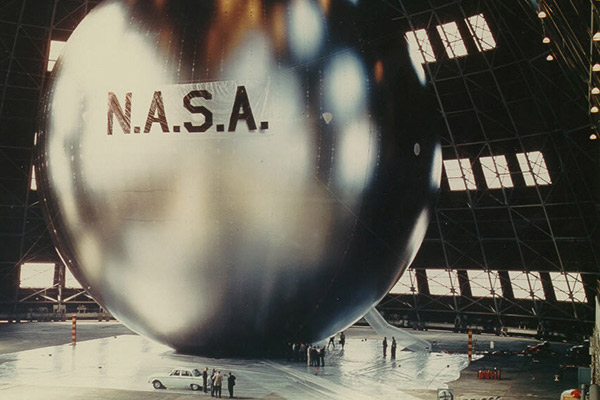

In 1957, Bernd and Hilla Becher launched a campaign to document the anonymous and often-disused manufacturing and domestic buildings they encountered in the abandoned wasteland of postindustrial Europe. Starting with the mining and steel-producing region around Siegen, Bernd’s hometown, and radiating out through the Ruhr Valley, the Bechers discovered an extraordinary proliferation of unique, anonymously designed vernacular structures in plain sight. In the coal-mining regions of England, France, Belgium, Italy, and ultimately the United States, the Bechers later photographed an encyclopedic range of industrial architectural forms, taking care to honor the generic categories while recording the subtle differences and the often idiosyncratic variations invented by local builders. In 1966 alone, the Bechers traveled for six months through England and Wales, visiting coal mining regions and industrial revolution relics around Manchester, Sheffield, and Nottingham. They were industrial archeologists, meticulously recording blast furnaces, lime kilns, cooling towers, water towers, gasometers, silos, factory buildings, timber-frame houses, pit winding towers, and coal tipples.

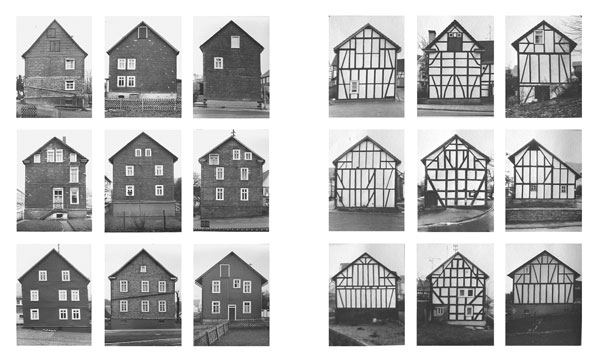

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Typology of Slate and Framework Houses (diptych), 2011 © Bernd and Hilla Becher. Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery

Working methodically, the itinerant Bechers followed a very deliberate practice depicting these architectural forms and complexes, producing sequences of separate photographs that looked at individual structures from every side, as well the surrounding natural and manmade contexts, though never showing workers or any other people. They derived inspiration from the precisionist approach of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) photographers August Sander, Karl Blossfeldt, and Albert Renger-Patzch of the 1920s, and utilizing a bulky large-format camera on a tripod, the Bechers photographed the specific character of each example of a type of construction as scientifically as possible. Every building was framed in exactly the same way: frontally, in isolation, from a reasonable distance, against a gray overcast sky.

Relating similar buildings according to their structural forms and original purposes, the Bechers created a vast taxonomy of modern architectural types facing eradication. “We didn’t really see it as artists, we saw it as something like natural history,” Hilla Becher noted in 2012. “So we also used the methods of natural history books, like comparing things, having the same species in different versions.” The Bechers exhibited these images in large, strictly ordered grids of nine, twelve, or sixteen photographs of nearly identical structures. They called these grids “typologies.” “The Typology is nothing but comparing and giving it a shape, giving it some sort of possibility to be looked at,” Hilla Becher said. “Otherwise, it would just be heaps of paper.” For the Bechers, these typologies were conceptual categories based on the general ideas used to sort a large body of information. For the rest of the world, the typologies were a revelation. Their structuralist approach and their interest in ordered sets and serial presentations were unusual in photography at the time; as a consequence, the Bechers often presented their work elsewhere, in austere Conceptual Art publications and exhibitions rather than the contexts of photography or architecture.

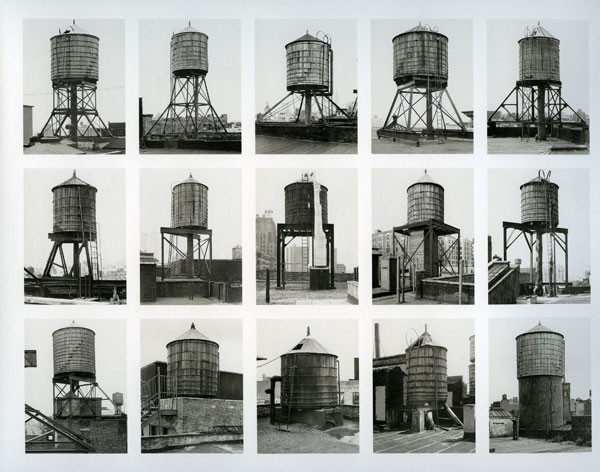

Bernd and Hilla Becher, New York Water Towers, 2003, © Bernd and Hilla Becher. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

Among the first to recognize the artistic significance of these typologies was American Minimal artist Carl Andre, who wrote in Artforum in 1972: “A partial catalogue of the typological subjects of Bernd and Hilla Becher includes: structures with the same function (all water towers); structures with the same function, but with different shapes (spherical, cylindrical, and conical water towers); structures with the same function and shape, but built with different materials (steel, cement, wood, brick, or some combination, such as wood and steel); structures with the same function, shape, and materials; comparative perspective views of ore and coal preparation plants; comparative frontal views of pithead towers; comparative and perspective views of pithead towers, high tension electrical pylons, blast furnaces, and factory buildings.” Andre’s straightforward listing conformed to his own rejection of narrative and style and his preference for neutral systemic or serial practices. Such an approach had long been advocated by the Bechers, who in 1970 called their first book on vernacular architecture Anonymous Sculptures and who eagerly participated in Conceptual and Minimal Art exhibitions. The photographs by the Bechers, and the artists surrounding them, were critical statements, which in part challenged the normative ideals of the postindustrial American culture of the 1960s and its emphasis on bland repetition and mechanical reproducibility.

Today, the influence of the Bechers is everywhere: in the widespread contemporary tendency toward serial documentary photography and in many artists’ interest in creating typologies or archival sequences of photographs. And, of course, they mentored a generation of students—the so-called Becher School—at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1976 to 1996. Among the students who assimilated the Bechers’ approach but often produced very different, large-scale color photographs in series were Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, Caio Resiewitz, and Elger Esser. Yet, despite this cadre of followers and the many accolades at Paris Photo and elsewhere, Bernd and Hilla Becher were outliers. They were uninterested in prevailing trends in art and photography, but offered instead a model for disciplined living and seeing. For five decades they pursued their singular project with astonishing tenacity and rigor, adhering to two simple guidelines: to record with exacting fidelity specific overlooked elements of everyday life and to organize that potentially ephemeral information into a form that creates new meaning. In essence, fleeting time was their subject, and photography allowed them to rescue sights that time has by now eradicated. In their elegant typologies, the blueprint of their attitude toward life endures.