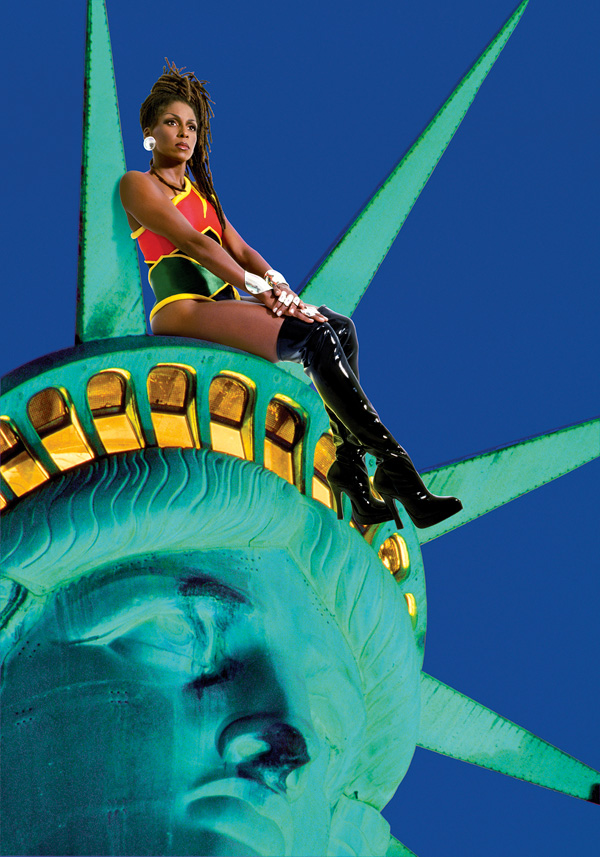

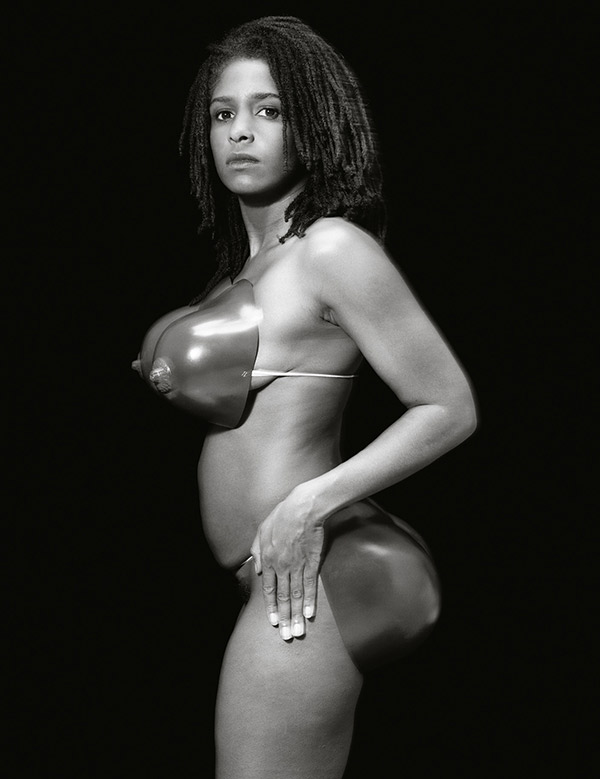

Renée Cox, Chillin’ with Liberty, 1998, from the series Rajé

Courtesy the artist

Renée Cox knows a thing or two about style. A former fashion model for Glamour and photographer for Essence, Cox had an early career in New York defined by the rapid pace of commercial assignments. In her thirties, turning to fine art photography, she began the first of several self-portrait series, portraying a multitude of stylized, powerful, and iconoclastic black women. These avatars—historic characters, fierce mothers, cosmopolitan socialites, and Afro-centric superheroes—are imbued with sexual agency and resolute confidence. Cutting a distinctive path in contemporary photography, Cox’s icons narrate a field of vision where black women perform for the world on their own terms.

Running in parallel to Cox’s photography is the evolving image of black women in popular American media and culture, including such icons as Angela Davis, Grace Jones, and Beyoncé. But the widespread consumption of images can erase a subject’s political message. In her classic 1994 essay “Afro Images,” Davis, a distinguished philosopher and activist, recalls that it was “both humiliating and humbling to discover that a single generation after the events that constructed me as a public personality, I am remembered as a hairdo.” Just as Davis sought to retake her own identity, Cox, in her photography, reimagines the lives of black women as central to debates about equality and respect. Here, Cox speaks with Uri McMillan about racial icons, stylish images, and the pursuit of power.

Courtesy the artist

Uri McMillan: Let’s begin with your journey from working in the milieu of fashion photography in New York and Paris for magazines like Glamour, Cosmopolitan, and Vogue Hommes to switching exclusively, in the 1990s, to fine art photography after the birth of your first son.

Renée Cox: I had an interest in photography from the day in high school when they made a mistake and put me in the advanced class. I was supposed to be with the beginners because I’d never done it before. So, I learned the practice of being in the darkroom and shooting right away. It was kind of nice, that moment when you’re young and you realize, Oh! That’s what my talent is.

Uri McMillan: What was your first job?

Cox: At Fiorucci, at the time a very trendy store on Fifty-Eighth Street in New York. I also did a little bit of modeling. My biggest modeling job was for Glamour in the early 1980s, posing as the girl who just graduated from college and was looking for a job in New York City—that was me. Brigitte Lacombe shot it. During the course of the four-day shoot, the fashion editor—Phyllis Posnick, now at Vogue—asked me if I had ever considered working at a fashion magazine. Previously, I had met with Deborah Turbeville, who gave me the blueprint. So, I didn’t have to think twice; I immediately jumped on it.

I did fashion for ten years. During that period, I shot a lot for Essence. If you look back at Essence in the 1980s, when it looked cool, that was usually me shooting. As a result, Spike Lee summoned me to shoot his poster for School Daze (1988) and some album covers—Gang Starr and the Jungle Brothers, for instance. I had a good little thing going. But then I got to the ten-year mark, had my first kid, and hit thirty. I was doing a lot of editorial then, and that work only had a twenty-eight-day life span. After that it was done.

McMillan: There’s no longevity to it, no permanence to the work.

Cox: Zero. I mean, maybe if you do the book, twenty years out. But that’s about it. I started thinking to myself, I can be an artist, too. I have things to say. Then I quickly realized I needed to go to grad school for anybody to take me seriously. I left the fashion industry for the School of Visual Arts, and then on to the Whitney Independent Study Program, arriving in this intellectual land where people spoke in tongues. The program started in September. By October, I knew I was pregnant. I came in and said, “I’m pregnant—with my second child.” People looked at me like, “Oh my God, are you sure? What are you going to do?” I was outraged. I had been through grad school and was not cutting my career off; I was just getting started. That’s how the series Yo Mama (1992–94) came about. I decided I’m going to give you pregnancy in your face—and that’s what I did. In other societies, women have allowed the males to dominate. I was like, No. Women are fucking strong. You make somebody in forty weeks; that’s pretty phenomenal. That’s the power of a woman.

McMillan: Let’s talk about icons and iconography. A large part of your practice has been the creation of new and affirming self-representations for black diasporic peoples, as a visual corrective to both art history and history writ large. And this has often taken the form of larger-than-life iconoclastic black female heroines, such as Rajé in your series Rajé, as well as portrayals of self-possessed erotic subjects. Who are your icons? What makes a powerful image? What are the complications in transforming black women into icons?

Cox: For me, the icon comes from within; it’s very organic. It’s a reaction. I refuse to be put down, squashed, or made invisible. I’m here, seven feet tall, larger than life. The thing that I use is the gaze. Ninety percent of the time, I’m looking back at the viewer looking at me. It’s about creating freedom. I’m not one of these black artists who’s trying to run away from blackness. There is no postblack. There’s no post; it’s only the present.

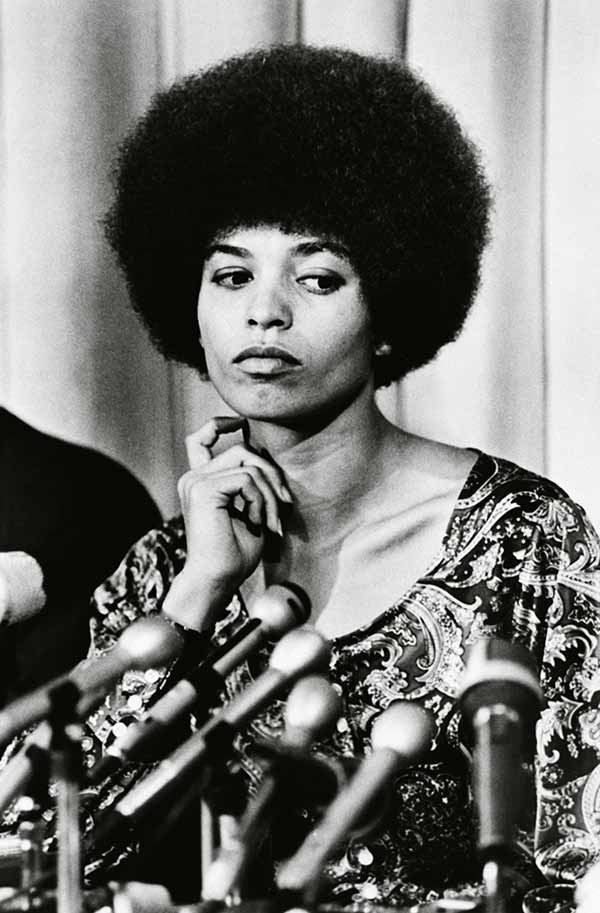

© Bettmann/Getty Images

McMillan: In regard to the black-power era of the late 1960s and early ’70s, no one’s image has been circulated as much as that of Angela Davis. She is perceived as the embodiment of an era, or in her words, “a nostalgic surrogate for historical memory.” Yet, she has been very critical of the way her image travels. In her 1994 essay “Afro Images,” she discusses her alarm at the way indelible images of herself, such as the FBI’s notorious 1971 wanted poster, or photographs of her speaking to crowds of protesters, were later decontextualized and dehistoricized.

Cox: She became an icon—for her hair.

McMillan: Right. She was reduced to her now stylish Afro, transforming a “politics of liberation to a politics of fashion.” What are your thoughts on Angela Davis as the prototypical black feminist icon?

Cox: At the time, she was doing something very revolutionary, but it becomes flattened when you only get the superficial sound bites about the Panthers that appeal to ignorant people. This flattening has happened with my work as well. The Rajé series, for instance, had a lot of meaning and depth behind every one of those images. Yet, people would say to me, “How often do you work out?” What do you mean, how often do I work out? This is not a Jane Fonda workout video! If you’re a fit black woman, there’s this whole exotic longing for the other.

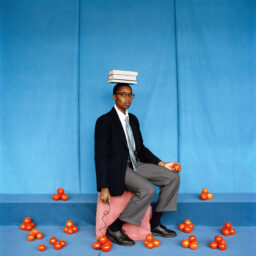

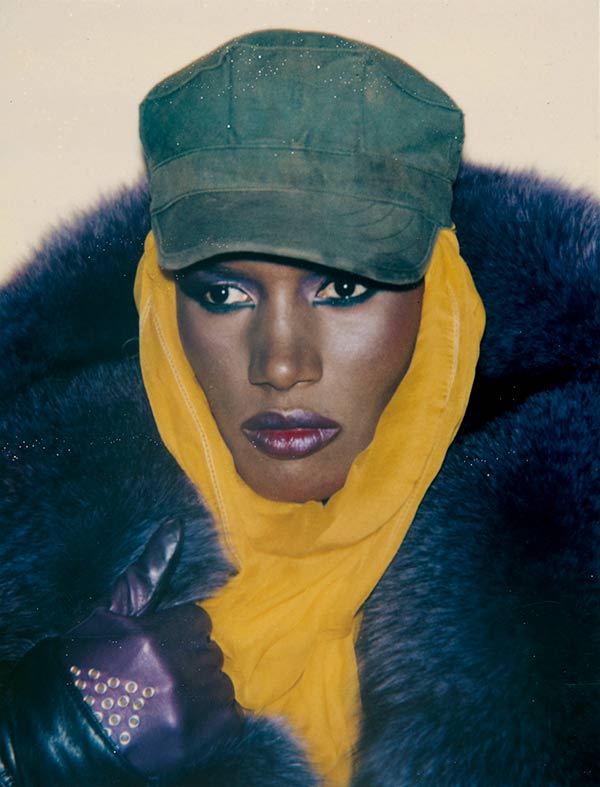

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society, New York, and courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

McMillan: Grace Jones, on the other hand, is an icon of a much different order, understood as sine qua non to the 1970s downtown party network. Similarly exoticized for her sleek athleticism, she’s a striking counterpart to your own work, particularly her distinct dynamism as a visual subject. You also have amazingly similar geographic trajectories—Jamaica, Syracuse, Paris, and New York City.

Cox: We definitely had a lot in common, for sure. She obviously had a lot of insight in how she wanted to be portrayed. Yet, I can’t negate the fact that she collaborated with Jean-Paul Goude. He’s the one who can present the idea of using her in Peugeot advertisements and the company says, “Whoo, yeah!”

McMillan: Finally, perhaps inevitably, we come to Beyoncé. To consider Beyoncé as a feminist icon is a bit ironic, since she initially expressed ambivalence to the term feminist and to her songs, such as “Bootylicious,” being labeled feminist anthems. She has now apparently embraced the term—she showed off an enormous light-up sign reading FEMINIST at a 2014 concert—and also through specific angles, such as sampling Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 TED Talk “We should all be feminists.” I am curious as to your thoughts on her, particularly since she has become the black female icon.

Cox: Before speaking with you, I said to my assistant, “Let me try to be politically correct here. I don’t want the ‘Bey-hive’ coming after me.” She’s talented and has a good team around her to make her look good. I give her that. But … [laughs].

© the artist/Getty Images

McMillan: Visually, her very clear recycling of black-power sartorial aesthetics, in her performance of “Formation” for the 2016 Super Bowl, circles us back to Angela Davis. In my opinion, it was a bit problematic.

Cox: Yes, because it’s not coming from any real place. I didn’t hear her say “Stop killing black young men” and see her put her fists up in the air. No, she didn’t do that. I’m sorry, but to me that was pure nothingness. How did that performance represent the Black Panthers? The Black Panthers were trying to get breakfast for kids and trying to protect their communities, before they were destroyed by Hoover and the FBI. You’re just talking about the sensational part of the Panthers: the guns, the black leather jacket, and the black beret.

McMillan: So her “feminism” is just on the surface?

Cox: “I’m a feminist.” “Put a ring on it.” Oh, okay, great. Come on! I don’t even call myself a feminist. I just believe that women should have the same rights as men, and be treated and paid accordingly. Simple. I hate to say it, but the whole feminist movement was for white women who lived in the suburbs, and in some ways they killed it for themselves. Men have been treating women badly for centuries. So continue with the chivalry.

McMillan: What resurfaces in Beyoncé are the manifold historical tensions between white and black feminisms, academic and mass feminisms, and the presence of unruly black female bodies in the visual sphere. In your own work, you’ve often brought history to the stage. Take Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman, also known as the Hottentot Venus, a Khoikhoi woman who was born in South Africa in the late eighteenth century and later paraded around Europe as a form of public entertainment. Her story is ground zero for the grisly objectification of the black female body, as well as its visual coding as grotesque, fleshy excess, dark fantasy, and pathology. Which makes it all the more remarkable that your restaging of this history—and body—in Hott-en-tot is playful while revealing the hyperbole and stereotypes embedded in these erotic fantasies. By deconstructing the black female body, you reveal the indelible, sticky myths behind it.

Cox: I was horrified when I first read about her and found out she was taken to Europe and toured around like a specimen, as if to justify colonization. I’m certainly not ashamed of her; that’s how some of our people look.

Courtesy the artist

McMillan: How did you make this image?

Cox: It came together in a costume store. I saw the big tits and the big ass in plastic! And I said, “Aha, there it is,” and took it back to my studio, and shot it. That’s Hott-en-tot. That’s how it came about.

McMillan: Nobody would ever think about tracing that costume back to a figure like the Hottentot Venus. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen a random white teenager wear those body parts during Halloween, and not think anything about it being controversial or offensive.

Cox: Well, that’s the lack of awareness. They don’t know the story of the Hottentot Venus. They don’t know what their European brethren and sistren were doing back then, how they were exploiting people.

McMillan: I taught Suzan-Lori Parks’s 1996 play Venus this past spring; literally none of my students had ever heard of the Hottentot Venus. I did have one black female student who was really moved by it. She said to me, “Thank you so much for teaching this and for making me realize I’m not a freak.” I was stunned.

Cox: I would have been, like, “Girl, why did you think you were a freak anyway? Who told you you’re a freak, and why did you believe them?” But, that’s how the woman was built. End of story.

McMillan: The spectacle isn’t about her. It’s actually about the people who made her into one.

Cox: Exactly. That was the thing that I liked about Haile Gerima’s Sankofa (1993) and Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013). I heard people say, “Why are we doing another slavery movie?” Because some of us were slaves, and were treated very badly—that’s why. You know, I went to this plantation down in South Carolina, Magnolia. You’ve got to drive a mile before you get to the big house and the vegetation is so dense, you can’t even see your hand in front of you if you held it out. I’m saying to my son that these people had to cut this down and level it. A mile’s worth of land; flat as a golf course now. Then, we get up to the big house, and they wanted thirty dollars from me to go on a tour. I was like, “Are you kidding?” They had not seen the likes of me before. You have white people walking around with their baby strollers, saying, “The gardens are so lovely.” Yet, for me, this is like Auschwitz or Dachau; it’s a death camp. I went off. I said, “When you see a black person coming up the drive, you need to roll out the red carpet. You need to have people outside going, ‘We’re so sorry that our ancestors were so degenerate and did the thing that they did.’” That’s really what needs to be happening, not asking me for thirty dollars to go on some damn tour.

Courtesy the artist

McMillan: In that spirit, you transform dispossession into self-possession. Baby Back continues such work, staging the reclining black female nude—a contested object in its own right, since the female nude is usually associated with the white female body. You use black portraiture as a counter- narrative to upend Manet’s Olympia. Black women move from the margins of the frame to the center. Yet, even here, there is a subversive edge—the fire-engine-red patent-leather high heels, and the black leather whip, which references BDSM subcultures as it also alludes to histories of enslavement.

Cox: Exactly. If anybody’s going to be using the whip, it’s going to be me. It’s not going to be used on me. I’ll be using it. Okay? [laughs]

McMillan: And the shoes?

Cox: Well, they’re sexy.

Courtesy the artist

McMillan: In your ongoing series The Discreet Charm of the Bougies, there is a provocative metatextuality happening. You stage yourself as the paradigmatic black housewife, a woman of stature, class, and status—signaled by the pearls, poodle, and especially the nameless white female servant. Yet, that is partly undercut by the haunting of that character by the huge photograph she owns: Yo Mama, your own picture, featuring you as a nude mother clad in nothing but black high heels, holding your son. What were your motivations for this series?

Cox: The Discreet Charm of the Bougies is a psychodrama. The star’s name is Missy. She lives a very privileged life. She is very much self-aware, but she is very much alone. She’s got a white maid, but she’s blasé about it. It’s expected, in a way. Throughout this series, you see her going from living in this depressive, unconscious state to becoming enlightened and realizing she can live a life of joy. Obviously, it’s my own personal journey. Because for me, one of the key things was when I realized I didn’t need anybody to validate me except myself.

McMillan: In Lady of the Night, Missy is reincarnated as an eroticized version of herself, seemingly liberated from her pristine surroundings and conservative attire. Missy’s attainment of power is linked to gaining sexual power, as well.

Cox: Right. In The Jump Off, she’s in bed with a guy, with the pills and the rum—because she’s Jamaican—but she also has a book about Maroon society. Yet, she’s caught up in a lifestyle, and at that juncture of the series, she doesn’t yet know how to get out. Her transition occurs when she’s traveling over in Asia, in Bali, and Cambodia, and the wig that she’s been wearing the whole time is gone.

McMillan: You said you don’t call yourself a feminist, but power, and specifically the power women generate for themselves, has been one of your enduring themes. How have your ideas about power evolved since you first began taking photographs?

Cox: Once you have the power, you always have the power. The power comes from within. It’s not a state of mind: the real power comes from the heart. All women have it. It’s a matter of cultivating—and realizing—that power. You have to feel it.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, Issue 225, “On Feminism.”