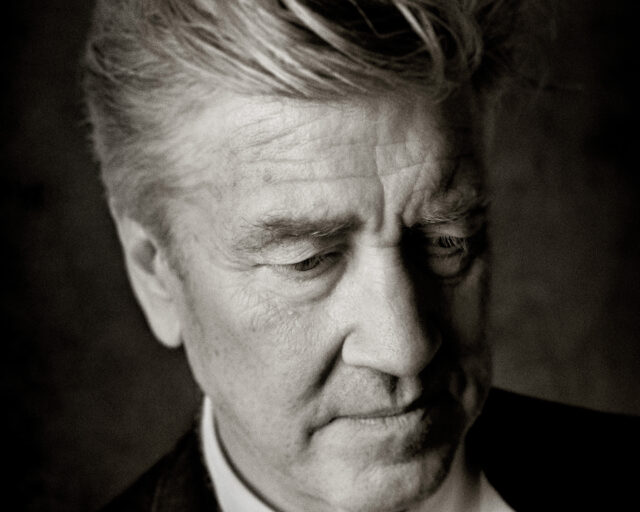

Alec Soth Revisits His Legendary First Book

In 2004, Alec Soth published his seminal monograph Sleeping by the Mississippi to widespread critical acclaim, helping to establish both his own and the book’s place firmly within twenty-first-century photographic culture. After being out of print for nearly a decade, a new edition of Sleeping by the Mississippi was released by MACK earlier this autumn. Although it bears a striking resemblance to the original first edition, it also contains a number of subtle and revealing tweaks, and once again affirms the book’s remarkable power, relevance, and long-lasting resonance.

Alec Soth, Patrick, Palm Sunday, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Aaron Schuman: To start, what’s it like for you to revisit Sleeping by the Mississippi today, thirteen years after it was first published?

Alec Soth: I’ve been in the process of looking back for some time now—not just to Sleeping by the Mississippi, but to my original motivations for getting into photography. As I’ve gotten older, and also as commerce has come into play, my relationship to the medium has changed; it’s so easy to get jaded. So, recently, I’ve been investigating those primal feelings that I had at the start. Reprinting this book made me think about the time when I first fell in love with the medium, but had also reached a certain level of competence; that’s the sweet spot. I’ve talked with many people about photographers’ first books—I think that what often makes them so strong is the photographer’s newness mixed with a certain amount of attained skill, but still without knowing too much. For a long time after making Sleeping by the Mississippi, I didn’t look at it because I just saw its flaws. But now I get that the flaws—or its naïveté—were essential to my passion at the time.

Schuman: Could you talk me through an example of a “naïve flaw” within Sleeping by the Mississippi?

Soth: As you can imagine, I’m still reluctant to point flaws out, but there are all sorts of things. For example, there’s one image of a hospital bed in a house, and too many things are perfectly placed within it. I had a tendency to fill up the picture and overdo it. That particular photo was made in a peculiar little town. I saw this amazing house, and then I saw the eerie hospital bed. It was one of those magical experiences that speaks to that primal feeling of photographers when they’re starting out, to the adventure of it. At the time, I didn’t have a career or this big identity as a photographer, so I was almost making sculptures and then photographing them; I was moving stuff around, playing in that space; there was a joyousness to it. But as a picture that eventually became part of a photobook with a quasi-documentary vibe, it’s kind of problematic. I wouldn’t do it that way now; maybe I’d strip things away and leave the bed itself. Also, beneath the bed in that picture there’s a hole in the floor; I love that. Today I might let that hole exist on its own.

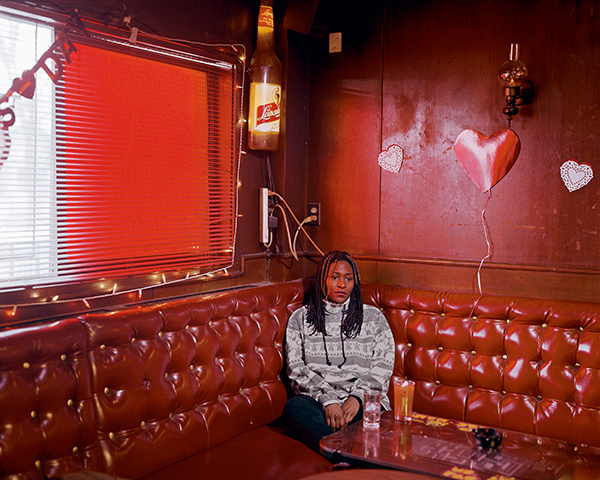

Alec Soth, Kym, Polish Palace, Minneapolis, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: Obviously you can’t change the photographs themselves, but in reprinting a book there’s the opportunity to revise or “remaster” it in various ways, retrospectively. Yet in the new MACK edition, you’ve remained relatively true to the original.

Soth: This book has a peculiar little history. The first edition was done with Steidl; I loved the cover and everything else—it was perfect. We thought about reprinting it as a soft-cover trade edition, but for whatever reason we moved back to hardcover, and put a more commercial picture on the front—the one of Charles holding the airplanes—which in retrospect was a mistake. Nevertheless, that sold out quickly so we decided to do a third edition, but by then it felt like cheating to go back to the first cover, so I figured we should keep using different images on the cover. Then that edition sold out, things kind of stalled, I moved on to a different publisher, and the book stopped being reprinted. Years passed, and I occasionally thought about reprinting it again, but felt that it should probably coincide with the twentieth anniversary or whatever. Then last year, Michael Mack suggested we do it again, and I thought, Why not—let’s just do it and make it available. But there wasn’t any particular reason to do it, so I figured we could finally reprint it like the first edition: same essays, sequence, no changes. Then gradually, tiny little tweaks happened. At some point I decided to put one new picture in, at the beginning of the book. Originally, I’d made some photographs at the headwaters of the Mississippi, but even in 2004 I didn’t like them, and using one of those would have been a very obvious way to start the book. When I looked at my pictures again recently, I stumbled across a photo that’s not of the headwaters but looks like what the Mississippi might have been before mankind. In 2004, that picture wasn’t usable, because the first edition was made entirely from contact prints, and this particular image had vignetting in the sky. But today I can take the vignetting out digitally, so I introduced it into the new edition, before the title, and it really changes the feeling of the book. I liked the idea of starting the book with this very primal picture.

Alec Soth, Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, 2004, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: You’ve also made a slight change to the back cover of the new edition, incorporating a picture that depicts the Mississippi River. In the past, you’ve explained that you were reluctant for the book to be interpreted as a project literally about the Mississippi—the river was one underlying thread that tied it all together, but it wasn’t the focus. So it’s intriguing that both the newly added image—the “primal” landscape—and also the back cover are introducing the river back into the work.

Soth: It’s true. After Sleeping by the Mississippi I did Niagara (Steidl, 2006), and in that book I showed Niagara Falls a number of times. I’ve thought that if I did Sleeping by the Mississippi now I’d probably make more river-related pictures, which totally contradicts what I often say about it not being about the river, but I just think I’d have that impulse.

Schuman: You’ve added another new image at the end of the book—a picture of a large ball of twine in the corner of a room that’s been roughly stripped of its wallpaper.

Soth: I really love that picture, and regretted not including it in the first edition. But there’s always the page-count situation, which is something many readers may not consider: because of the way the signatures work within a book, you can only have a certain number of pages. Practical things like this came into the process of editing back then as well. But I have a real affinity for that picture. To me, so much of Sleeping by the Mississippi is about being creative in a modest way. I love thinking about someone collecting string, making this ball, and getting creative satisfaction from wrapping it larger and larger.

Alec Soth, Green Island, Iowa (Ball of String), 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: You just mentioned how the practicalities of bookmaking often come into play when making various creative decisions. In returning to this book, what other aspects of this were you reminded of?

Soth: What was crazy about the first edition of Sleeping by the Mississippi was how fast so many major decisions were made. Originally, there were spreads with two pictures on facing pages, and at the very last minute I changed my mind, deciding to go with one image per spread; the original cover was decided upon very quickly; and so on. All those little decisions affected the book, so that’s something that I’ve kept in mind with other projects. It’s dangerous to work something to death, and sometimes—like when you make spontaneous choices photographing—you have to make spontaneous decisions when it comes to the edit and design of a book, in order to give it energy. That can be risky, and you make mistakes. I’ve made many mistakes in the past. But even with something relatively minor, like the addition of two pictures—I could fret over it for months, and ask hundreds of people if it works or not. But sometimes it’s fun to roll the dice and see what happens. Every decision comes into play. In the new edition, the color of the endpapers is different than in the original, and even something as seemingly minor as endpapers really helps give feeling to the book.

Schuman: The new edition’s endpapers are burnt orange, rather than the original white.

Soth: Exactly. An endpaper can give you this splash of color that introduces a subtle mood. One of the things that I learned early on as a photographer was that I knew nothing about design. So when it comes to a decision like that, I’ll ask them to suggest options. That burnt orange was one of the colors that MACK suggested, and it sets the mood perfectly. I haven’t lived with it very long, but I can already tell that it’s affecting my feeling for this edition: it’s like when filmmakers tint their film slightly amber, or how the music that plays while the credits are rolling subtly affects the feelings you carry with you when you leave a movie theater. The endpaper, in this very subtle way, gives this suggestion of feeling.

Alec Soth, Mother and daughter, Davenport, Iowa, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: Speaking of tint, when I looked at the first edition and new edition side-by-side, I noticed that there was a hint of warmth in the printing of the first edition, whereas the photographs in the new edition have a slightly crisper, more neutral feel.

Soth: There are a couple of factors there. Firstly, the paper has shifted; the original paper had whiteners in it that gave it more pop, but these yellow over time, particularly on the edges. To be honest, I can’t really tell how much of it is yellowing versus the tone of the original printing anymore—but yes, in the new edition we did try to correct this, and the pictures probably look a bit cooler overall. Plus, I see color differently now and have a better sense of printing. Also, the technology has changed in epic ways. I’m not an expert in printing by any means, but technological changes always come into play—even that stuff about optical whiteners, which I don’t really understand, keeps changing. And of course, there have been nine billion changes in terms of scanning and so on. So I mean, if Stephen Shore makes a new print of a 1970s image today, is he going to make it super-yellow? No. Don’t get me wrong—I might love the first edition of Robert Adams’s Summer Nights, and originally fall in love with the richness of all of the blacks; and then it gets reprinted, and all of a sudden it’s on nicer paper, and there are new details in the shadows. I still love the first one because my heart fell in love with it, but I also know how the new one is better. So, I would never reprint something poorly on purpose—and by no means am I saying the Sleeping by the Mississippi was poorly printed in the first case, which it definitely wasn’t—but changes happen, and like everyone I roll with them.

Schuman: When Sleeping by the Mississippi was released, it rapidly gained momentum and quickly became an established part of the “canon” of both photobooks and photography at large. What was that experience like for you?

Soth: It was totally unexpected, and I still don’t think it makes any sense. There was just no reason for it to become such a big thing. In a funny way, if it were to be published for the first time right now—because of Trump, Middle America, and all that—I could see why it might resonate. But back then there was no particular reason for it to become so huge; it still seems arbitrary and baffling. That said, I’m really happy that it was that book, because it is so profoundly connected to my basic impulses. Like the picture of Charles holding the airplanes—I’m so glad that’s my best-known photograph, firstly because I like it, and secondly because it’s about all of the things I’m still interested in.

Alec Soth, Charles, Vasa, Minnesota, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: Given the current issues in America that you mention—Trump, Middle America, etc.—do you feel like this book has taken on new meanings, or could evoke a sense of nostalgia?

Soth: The problematic part of talking about politics in relationship to this book is that I’ve always been a big defender of Middle America, saying that it’s far more interesting and complicated than people give it credit for. But I’ve become a little skeptical, sometimes thinking, Was I an idiot? Was I super naïve? Partly it’s because I haven’t been traveling in that part of the world very much in the last year, so I’m out of touch with real human lives, and am getting too much information from TV and media coverage. In terms of “nostalgia,” 9/11 is the ultimate turning point in terms of “before” and “after” in my life, and I’m genuinely nostalgic for pre-9/11. A lot of the pictures in Sleeping by the Mississippi were made before 9/11, and many were taken after, so it crosses that threshold. It’s not so much that I’m nostalgic for that time in history, but as a photographer it was exciting to be making something back then, and in making this new edition I’m able to feel it all again.

Schuman: Speaking of which, you’ve removed only one picture from the original edit—a snapshot of you standing on a ladder behind an 8-by-10 camera, with your head buried underneath a dark cloth, in the midst of a snowy field.

Soth: That picture was made at the beginning of my biggest trip for that project, probably around 2001, and was taken with a very early digital camera. Someone was driving by and they pulled over, wondering what was happening. So I went up and talked to them, and then said, “Hey, would you mind taking a picture of me with this camera?” and they took that picture. But the original digital file is long gone, so part of the issue with reprinting it was that we couldn’t find the file.

Alec Soth, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: But surely you could have scanned it from one of the book’s earlier editions?

Soth: Okay—as you well know, I’ve always been kind of embarrassed about that picture. But in my defense, there were two points to it. First, in a lot of photobooks from the 1970s you’d have this page where the photographer would list all of their technical information—what kind of camera they used, what film, what lens, etc.—and for a young photographer it’s the best, because you get all of that technical information, and you also get to imagine what it’s actually like to take the pictures. Second, there’s that picture of Joel Meyerowitz on the back of Cape Light, where he’s standing next to his 8-by-10 camera with his shirt off—I love that picture. So I think that’s what I was trying to do with that picture in the original version of Sleeping by the Mississippi. I could have kept it in this time around, but I couldn’t stomach it. I was self-conscious about putting it in again thirteen years later; I guess not being able to find the original file provided a good enough excuse to get rid of it.

Schuman: Considering all that’s happened to you since Sleeping by the Mississippi was first published, is it strange for you to look back at that anonymous, “naïve,” “passionate” kid standing on a ladder in the cold, entirely focused on trying to make a good picture?

Soth: That’s the thing about the release of this new edition—I’m currently in the thick of thinking about my earliest photographic impulses, and have been consciously trying to get back into that headspace. So the timing is quite good. When I was first making Sleeping by the Mississippi, I’d reached a point where I thought, No one cares—I can just do what I want, and it doesn’t matter. And lately, I’ve taken a period of time to just do whatever I want, even if that means making sculptures or doing sound pieces. They may never see the light of day, but I’ve given myself the space nonetheless. That’s the feeling I’m after, and that’s what Sleeping by the Mississippi represents to me. Apart from how it got out into the world, the actual shooting of that book had this incredible fairy dust all over it; it was magical and filled with the best luck. I now know that photography isn’t always like that, so this book is still a very special thing.