Robert Frank’s Genre-Bending Collaborations with Musicians

Patti Smith, Tom Waits, and the Rolling Stones liked Frank because he turned a sympathetic eye to the margins of American experience.

Robert Frank, Bar – Las Vegas, Nevada, 1956

Robert Frank spent the summer of 1972 crisscrossing America—not in pursuit of the lyrical social documentary for which he was already famed, but as part of the Rolling Stones’ forty-eight-date mobile bacchanal. It had been three years since the disastrous show at the Altamont Speedway, and the band was stateside again, on the heels of a recording session in the south of France that is now etched in the annals of debauched rock excess. The tour was no exception—sex and drugs and everything else, all later mordantly recounted by Truman Capote to Andy Warhol in the pages of the magazine named for the group. The novelist registered his surprise that so much of it was unabashedly documented, that Frank was always there, camera at hand.

In many ways, the tour marked a return for Frank as well. From 1955 to 1957, he made eighty-three pictures that would be published the following year in Europe as the book The Americans, and republished in 1960 with an introduction by the then quintessential avatar of the road trip, Jack Kerouac. The Beat wanderer observed that a musical quality suffused Frank’s frame—the Swiss-born photographer was drawn to the country’s lonely jukeboxes, people swaying at roadside dives, or riders in a convertible, ablur in motion. The book encapsulated the broad humanism and compositional immediacy that drove art photography well into the 1960s, solidifying Frank’s status among a younger generation (including his lifelong friend Danny Lyon) as a lodestar who chronicled a turbulent era.

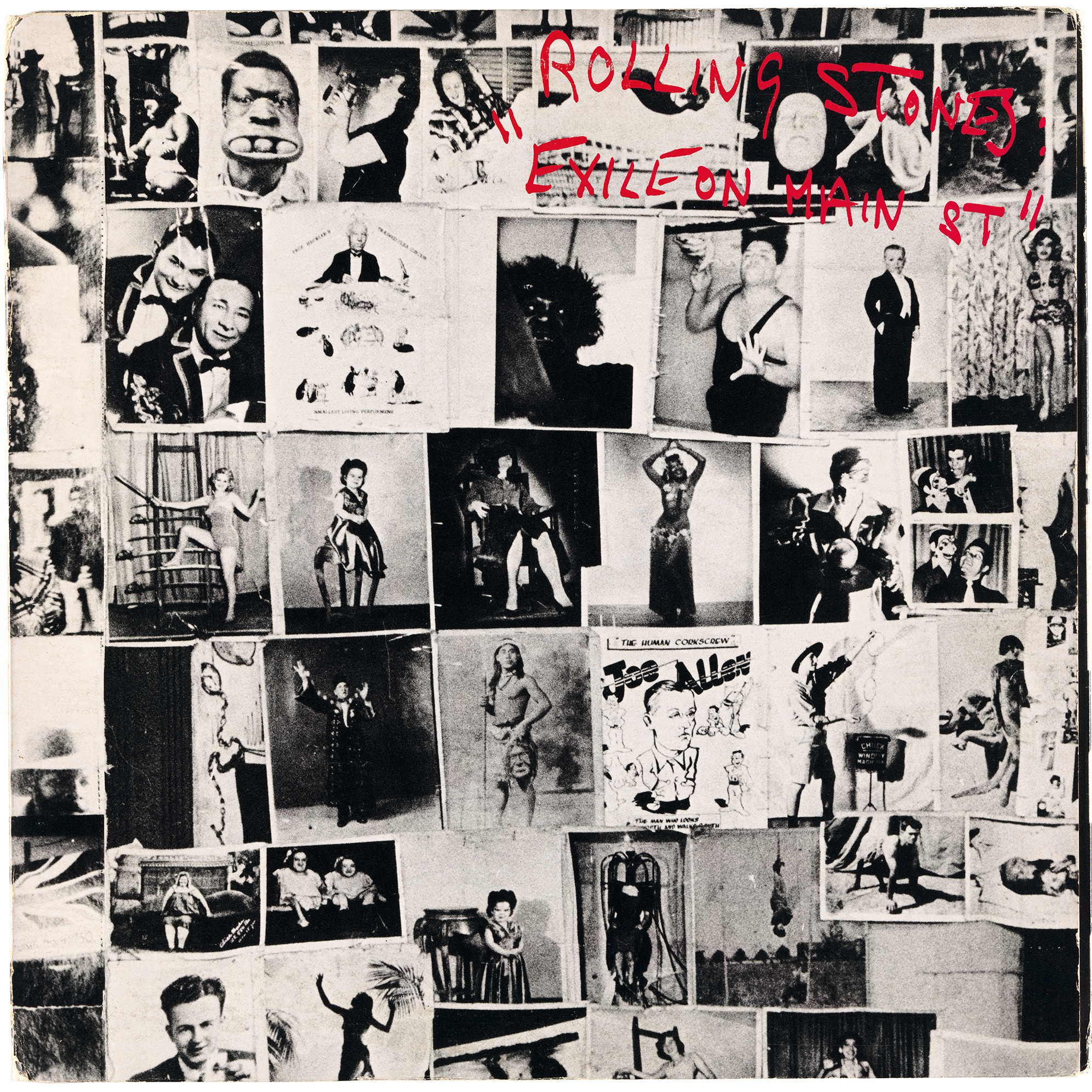

The trouble with finding such success early on is that one’s career is always measured against it, before and after. Ironically, the vast majority of Frank’s varied output in photography, film, and performance, and his participation in the electric Lower Manhattan scene of the 1960s, happened after The Americans. But those genre-bending collaborations are lesser known—an imbalance that the Museum of Modern Art’s current show Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue seeks to correct. Certainly, his episode with the Stones was but a high-profile instance of the ways in which Frank was less a lone photographer and, instead, a connector in a larger creative milieu. When he visited the band in LA, where they were wrapping Exile on Main Street, everyone seemed to click, and Frank was invited to shoot and design elements of the LP art (he had already captured stirring images for the mountain-folk outfit the New Lost City Ramblers) and to make an entry in the now venerable genre of auteurist concert film.

In those days, albums were events, gatefolds and liner notes scrutinized with Talmudic attention. For Exile on Main Street, Frank photographed the Stones in LA and New York but also interspersed older pictures, collaging and overlaying them with text. The iconic cover sequence of Arbus-esque carnival performers was actually a single image from The Americans rolls of the 1950s, taken from a board displayed at Hubert’s Flea Circus and Museum on West 42nd Street. The photograph was already well-known by misleading titles such as Tattoo Parlor, 8th Avenue, New York City. As RJ Smith noted in his biography of Frank, the shifty titling foreshadowed the sort of visual remixing at play on the Exile on Main Street cover and throughout the photographer’s career. Frank seemed keen to dirty up his image before it settled into hagiography, letting the meaning of his pictures drift by putting them in new contexts.

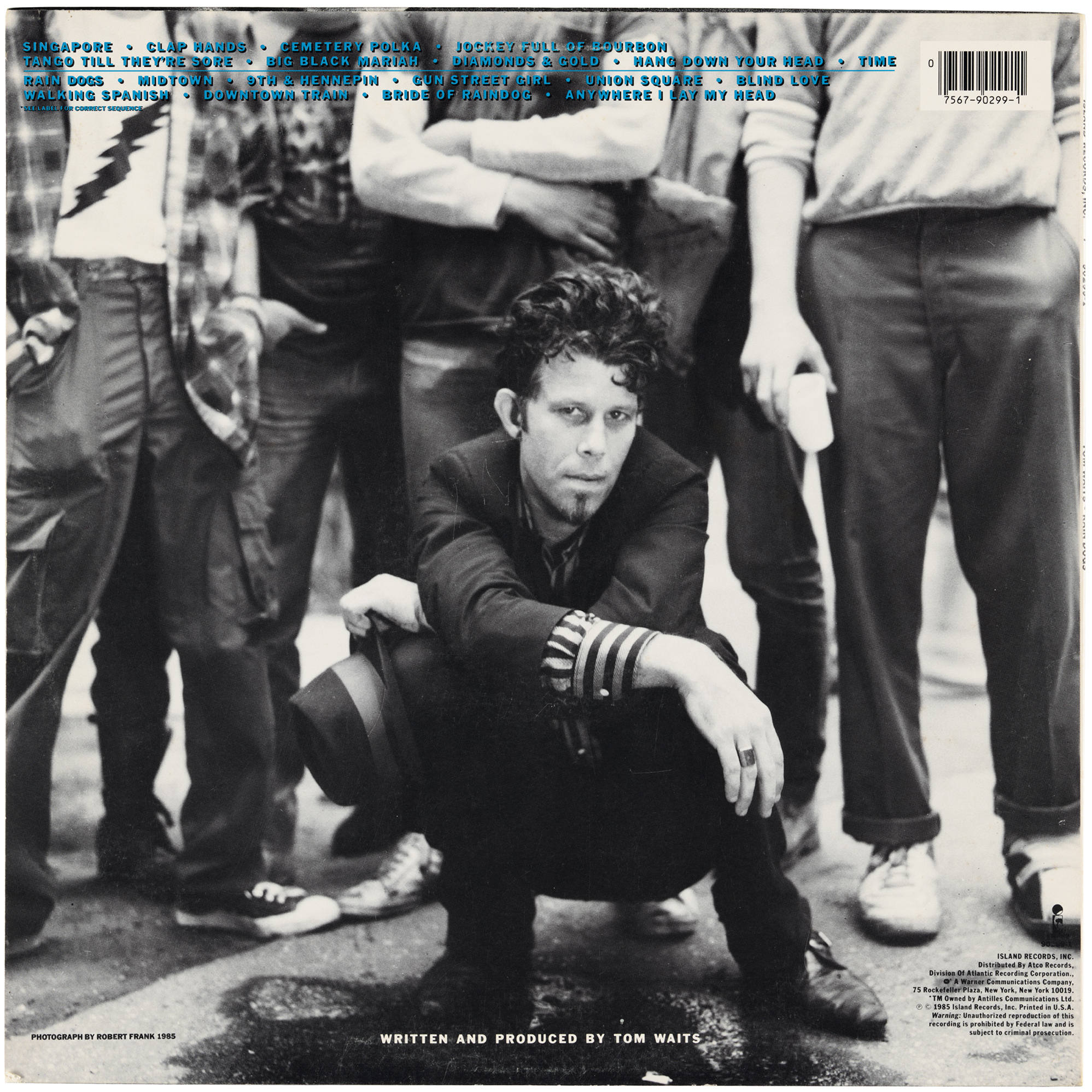

Musicians liked Frank because he turned a sympathetic eye to the margins of the American experience, foregrounding its grubbier contours. Although much of his later life was spent in the artists’ enclave of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia (alongside Joan Jonas, Richard Serra, and JoAnne Akalaitis), Frank always kept one foot in the Bowery, often turning up at haunts such as CBGB, where he met Patti Smith. The photojournalist Ted Barron recalls stumbling upon him in Tompkins Square Park one day in 1985, crouched on the pavement to capture a dashingly coiffed Tom Waits in conjunction with the Rain Dogs album. Waits was then cast in Frank’s 1987 feature made with Rudy Wurlitzer, Candy Mountain, about another road trip—a quest to Nova Scotia in search of a reclusive guitar luthier.

All images courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation; and Pace Gallery

That sort of recurrence of old acquaintances in new guises is a common thread in Frank’s many projects over the years. He met the British actor David Warrilow in 1975, and cast him in the full-color music video for New Order’s lesser-known 1989 track “Run.” More striking still was Frank’s collaboration with Smith on the music video for her 1996 song “Summer Cannibals.” Here, the roving lens and warped angles developed in his earlier stills inform his cinematic approach: they made Frank’s style feel newly fresh, and also of a piece with a host of black-and-white videos emblematic of the form’s maturation during the early 1990s. Both projects were typical examples of reinvention through tuning into the frequencies of other creators. In this way, the MoMA show reminds us that the shopworn tale of the solitary genius artist is rarely true: those icons always get by with a little help from their friends.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 256, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra.” Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through January 11, 2025.