Screen Legends

South Africa’s new media artists are transforming the digital world.

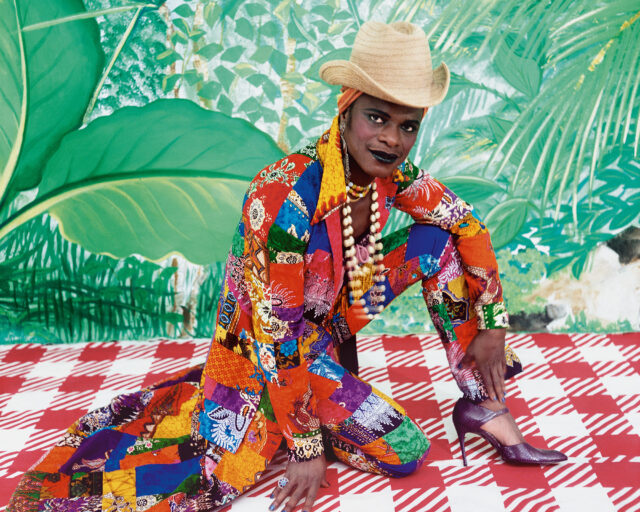

Amira Moraloki, FAKA, 2017

© and courtesy the artist and FAKA

Is the unending archive of visual references online more real than reality itself? In South Africa, Bogosi Sekhukhuni, CUSS Group, Tabita Rezaire, and FAKA are among the artists and art collectives working to reinterpret local realities and global visual cultures. By employing the aesthetic powers of online spaces, they create art that is enigmatic and nostalgic, ironic and socially conscious. But, notably, these artists are not confining their art to cyberspace; they are also exhibiting Internet-based work in galleries, museums, and biennials. By placing such art in traditional, physical venues of display, they are pushing viewers to create new tactics of engagement with pieces borne of online spaces.

Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Still from Simunye Systems Orientation, 2017. HD video, 7:23 minutes

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson Cape Town and Johannesburg

Bogosi Sekhukhuni’s Tumblr homepage is a GIF of the 1990s-era Canadian television program Animorphs. For South Africans in their twenties and thirties who were regular watchers of after-school cartoons screened by the South African Broadcasting Corporation, the reference is a nostalgic one. And while an example of the globalization of media, it is also illustrative of Sekhukhuni’s use of the hyperreal. Sekhukhuni creates his images, videos, and installations from a patchwork of references drawn from an array of similarly suggestive visual media, from local television ads to alien conspiracy videos. The user experience of his Tumblr contextualizes Sekhukhuni’s chosen media; for example, clicking on “feed” leads to YouTube videos with titles like “Avatar: The Last Hoodbender” or an interview with Lauryn Hill. These are mixed together with works by Sekhukhuni such as Orisha Totems (2016), previously displayed as large-scale hanging photo sheets at the 2nd Edition of the Kampala Biennale in Uganda. Onscreen, these triplicate portraits show the artist wearing light jeans and pastel T-shirts, photoshopped into imagined spaces of water, land, and sky that scroll as satisfyingly as a flip book. By interweaving original artwork with found footage, Sekhukhuni firmly places his practice within the aesthetic experience of the online space.

Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Still from Simunye Systems Orientation, 2017. HD video, 7:23 minutes

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Clicking instead on “OPEN TIME COVEN” leads to a page with an autoplaying video of a faux archaeological site/installation artwork at the 2016 Dakar Biennale. The accompanying text is simultaneously artist’s statement, institutional critique, and New Age spirituality drawn from African sources, underscoring the predominant theme across Sekhukhuni’s practice: the reevaluation of narratives about South Africa, the African continent, and black people, globally. His artwork pushes against a linear narrative of art history in which the West is home to modernity and postmodernity and Africa is home to the prehistoric, as illustrated by “authentic” wooden curios and masks bought by tourists. By reshaping the past and critiquing the present, his work offers us a utopian future.

Sekhukhuni has also worked with CUSS Group (Ravi Govender, Zamani Xolo, Jamal Nxedlana, Christopher Bryden McMichael, and Lex Trickett), an artist collective that uses similar tactics in their online presence. A web page they made in 2016 used the visual language of online scammers to sell an undefined product from the “Triomf Factory Shop.” At the 9th Berlin Biennale, in a work titled Nguni Arts International (2016), they created a storefront for this mythical business, sparsely stocked with innocuous, self-branded goods such as a fragrance and beer. It served as a front for their backroom activities: a program of live performances, closed to the public, but streamed into the front room. The storefront and its program of performances were made in collaboration with South African artists ANGEL-HO, FAKA, Megan Mace, and NTU, a collective founded by self-proclaimed tech healers Sekhukhuni, Nolan Oswald Dennis, and Tabita Rezaire.

Tabita Rezaire, Still from Seneb, 2016. HD video, 7:30 minutes

© the artist and courtesy the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Rezaire, a French Guianese Danish multimedia artist based in Johannesburg, also uses the Internet’s hyperreality as an artist’s tool. Her work shape-shifts as satire, educational lecture, and vaporwave music video. The wallpaper of her personal website is made up of screenshots contrasting Wikipedia entries of the words prophet (“not to be confused with Profit”) and profit (“not to be confused with Prophet”), in the center of which is an image of Rezaire sitting in the lotus position and dressed in a metallic spandex bodysuit. Every element of the site unsettles the perception of her work as either sincere or ironic, as it appears to mock itself while genuinely offering thoroughly argued strategies for healing and resistance against misogyny and racism, online and off.

The experience of watching the beginning of Rezaire’s video Hoetep Blessings (2016) is especially rooted in the online landscape: it makes use of an Urban Dictionary entry and Wikipedia to define the word hotep. While she gyrates to kitsch flute music in front of green-screen images of hieroglyphs and the Pyramids, Rezaire explains that hotep is an Egyptological term for htp, meaning “inner peace.” Hotep has been adapted by black communities to refer to men who position themselves as champions of black issues—men who would unironically use hotep as a greeting—while working to counteract black feminist and queer resistance with “traditional values.” Rezaire proposes that the word hotep be reclaimed. Her gyration functions as a feminist tool of this reclamation. Combined with numerology, Kiswahili etymology, chemistry, neurology, yoga, and ancestral knowledge, she instructs viewers how to go from “hotep to hoEtep”— how to resist and heal from regressive narratives about black female and queer sexuality by taking ownership of the digital landscape.

Tabita Rezaire, Still from Hoetep Blessings, 2016. HD video, 12:30 minutes

© the artist and courtesy the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

FAKA, an art duo formed by artists Thato Ramaisa and Buyani Duma, working under the alter egos Fela Gucci and Desire Marea, respectively, use visual culture on the Internet to reclaim the dialogues surrounding their race, sexuality, and class. As suggested by the name Fela Gucci, FAKA use a mash-up of African and Western references in the dress, music, and performance that appear in their videos. Riffing on pop-culture icons like Brenda Fassie and Bette Midler, they have become muses for and collaborators with photographers such as Musa N. Nxumalo, Kristin-Lee Moolman, and Jody Brand, and as well as the fashion and culture site Bubblegum Club.

FAKA’s video Isifundo Sokuqala (2016) is an assertive proclamation of their sexuality and physicality as queer black males. They writhe, dance, and pose wearing blond Afro wigs, gold chains, and elbow-length pink gloves in a house and neighborhood with all the markers of working-class South Africa. Set to a gqom soundtrack, a genre of music from the Durban underground house scene, Isifundo Sokuqala has the feel of a music video, and, in fact, is one, for a single of the same name on FAKA’s debut EP, BOTTOMS REVENGE (2016). Even so, the video’s aesthetic and its loose narrative make a strong statement, playing upon the homophobic discomfort of queer sexuality often found in South Africa. Working-class, queer South Africans are among the most severely affected by the country’s high rate of violent crime, due both to homophobia and their lack of access to the middle class’s high-walled security estates. As Sekhukhuni and Rezaire do with their multiplatform interventions, FAKA uses the online space to subvert hostile narratives through imagined realities and identity making.

The Internet “creates a metaphorical world in which we conduct our lives,” Mark Nunes wrote in a 1995 essay on Jean Baudrillard and cyberspace. “And the more ecstatic the promises of new, possible worlds, the more problematic the concept of ‘the world’ becomes.” Baudrillard himself theorized that a catastrophe would occur in the future when the sophistication of the simulation would surpass reality, “a hypertelic process in which we will have gone faster than our shadow.” Although we have not reached Baudrillard’s “catastrophic” phase, the placement artworks using the linguistic and visual conventions of the digital space into the physical world suggests that the hyperreal is in the process of surpassing the real.

Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Soul Contract Revocations; Dream Diary Season 2, Joyce, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Sekhukhuni, Rezaire, and FAKA have taken the Internet’s world-building, identity-creating capacities and used them in exhibitions at galleries, museums, and biennials that offer opportunities for audience engagement. Traditional art spaces give orderliness and accessibility to works that may seem obscure in the chaos of the online world. As Lerato Bereng, an associate director at the Stevenson gallery, told me, “I love the Internet and its infinity, but I acknowledge that the visual language of a web-based art intervention can leave one feeling technologically inadequate. This is part of the beauty, challenging the manner in which art is viewed, engaged with, and consumed. Artists such as Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Tabita Rezaire, the CUSS Group, and FAKA are part of a generation that have punctured the fabric of form and challenged the function of physical space.”

Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Simunye Summit 2010, 2017. Installation view at Stevenson, Johannesburg

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Even so, through the use of installation art and live performance, these artists use traditional venues of display to offer an impactful physical element to viewers. Sekhukhuni’s latest solo exhibition, Simunye Summit 2010 (2017), included videos mounted on rainbow-colored headboards and made use of colored lighting and large-scale projection. Rezaire’s staging of a public “kemetic yoga” session in the exhibition space, and her placement of a video onto a physically evocative object—the gynecological examination chair—in her recent solo show Exotic Trade (2017) is another example. Live performance gives FAKA’s music and movements, as seen at their performance at the 9th Berlin Biennale, Rectum River (2016) described as “a four-part healing sermon,” an immediacy that cannot be reproduced in the digital realm.

Tabita Rezaire, Still from Deep Down Tidal, 2017. HD video, 19 minutes.

© the artist and courtesy the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

What happens when our cultural touchstones, created online, are translated and reframed in physical spaces? Traditional venues might offer their institutional approval and turn the user experience into something that is still visually and conceptually striking, and perhaps more easily intelligible to viewers. However, globally, we are living online with an intimacy that far exceeds our interaction with any one physical space. “With Instagram pages functioning as portfolios or spaces in which to stage visual activism, I see the ‘interwebs’ as an alternate reality to the gallery cube. I think the Internet is an incredibly expansive platform and cannot be used like galleries or museums but is a platform of its own neighborhood,” Bereng suggested. “Online exhibitions are successful when the versatility and expansiveness of the medium is acknowledged, explored and pushed, not in the way one would use a gallery space or traditional artist website.”

Though the Internet still leans heavily toward the Western center and is populated by the patriarchal and imperialist structures that dominate the real world, through it the implements of cultural production are more easily accessible. South African artists are using the Internet and its visual languages to create provocative statements that dismantle harmful ideologies and propose more representative utopias to take their place.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

Read more from Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.