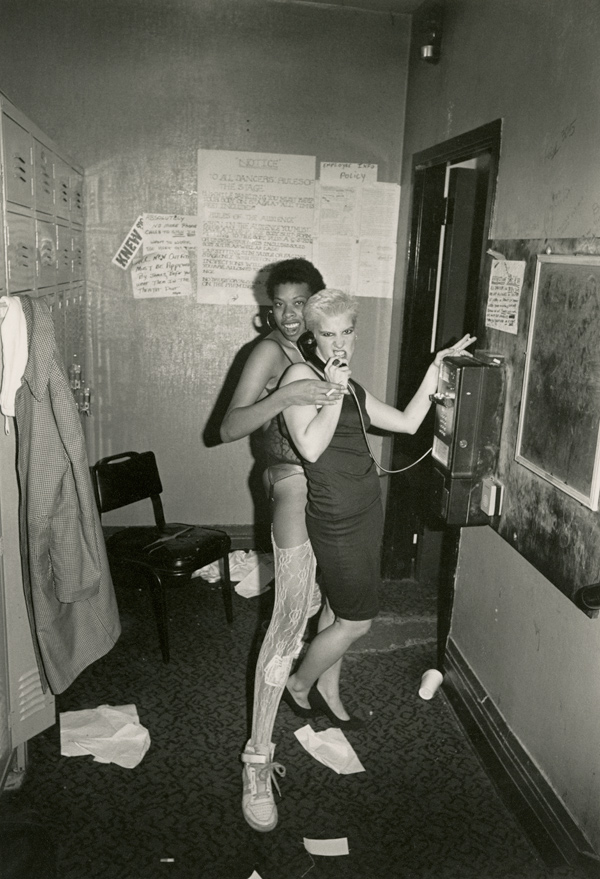

Leon Mostovoy, from the series Market Street Cinema, 1987-88

© the artist

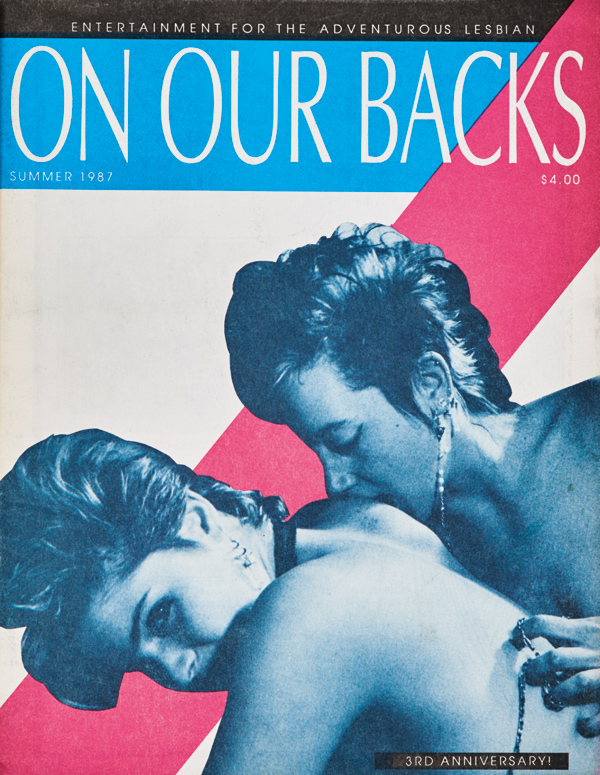

“For years we as lesbian-feminists have been fighting male pornography,” a reader named Donna from Washington, D.C., wrote. “It shocks and abhors me to find that women have stooped to the same methods.” To scan the letters pages of the San Francisco–based magazine On Our Backs, published from 1984 to 2005, is to find lesbian erotica thrown into relief against the backdrop of the feminist sex wars. Antagonisms that characterized the movement in the 1980s play out in an epistolary exchange, and through the rancor, a contrasting story emerges. “How different—bold—and wonderful to see (for my first time) women enjoying women,” another reader commented. “It makes me remember that I’m not alone in my thoughts, although fairly secluded in South Carolina,” says another. One reader gets right to the point: “A splendid aid to masturbation! Thanks!” Nestled among these letters are whetted appetites and desires unmet, a request for clarification on attraction between butches, a note about racial integration in the San Francisco leather scene, even a complaint about proofreading errors. A field of lesbian desire appears, one that was contested, shared, and shaped by contributors and readers alike.

The publication emerged at a juncture in feminist history known as the sex wars, a time of high-octane tensions between “pro-sex” and “anti-pornography” feminists. The two terms obscure the complexity of these debates yet gesture toward a stark ideological rift. To summarize, pro-sex feminists sought new languages for female desire. Feminist anti-pornography groups, such as Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media and Women Against Pornography, campaigned for increased legal sanctions on the production and circulation of pornographic material. Photography figured predominantly in this debate, both as a catalyst for antagonism and a means by which feminist affinities might be established and fantasies explored. In the context of these fraught and painful divisions, On Our Backs contributed to a burgeoning media through which images of lesbian sexuality were constructed and disseminated, lusted after and spurned.

Bertie Ramirez, cover of On Our Backs, Summer 1987

Courtesy the Lesbian Herstory Archives

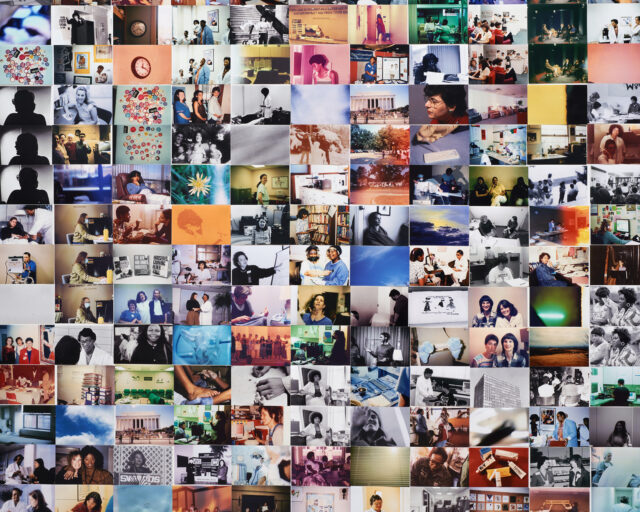

The magazine was an early platform for lesbian sex photography. Along with the Boston-based Bad Attitude, it carved out a space for others to emerge (Outrageous Women, Wicked Women, Quim, and Lezzie Smut, to name a few international examples that followed). In its first decade, On Our Backs was instrumental in shaping a culture organized around lesbian desire. The first editorial, written by Debi Sundahl and Myrna Elana, cofounding editor and publisher, respectively, introduces On Our Backs as an “offering” to the community with the aim of “sexual freedom, respect and empowerment for lesbians.” There were many who worked to realize this goal. Susie Bright, then the manager of Good Vibrations, a San Francisco shop selling sex toys for women, oversaw six years as editor in chief. Starting out as something of a sexual agony aunt, she wrote an advice column that became a trademark of the magazine. Nan Kinney, another founding editor, went to develop Fatale Media, a producer of lesbian erotica videos that by the end of the 1980s was the largest of its kind. Alongside essays, poetry, and graphic art, photography was key to realizing the ambitions of the magazine, and On Our Backs was shaped around a culture of image makers. Its smart black-and-white aesthetic was defined by photographers such as Honey Lee Cottrell, Tee Corinne, Morgan Gwenwald, Jill Posener, Leon Mostovoy, and Katie Niles. Photography stories, reportage, constructed scenes, and advertising images mixed with informative articles, erotic fiction, and, importantly, personals. Later, people like Lulu Belliveau and Phyllis Christopher would be instrumental in developing an ever more stylish visual language that continued to challenge the paucity of available images of lesbians in mainstream culture.

Phyllis Christopher, Alley South of Market, San Francisco, 1997

Courtesy the Artist

There are perhaps two intertwined genealogies here. One is within histories of feminism, the other within those of homosexual culture. As often happens in politics, the sex wars played out as a dispute not only between opposing factions but also different generations. This division caricatured second-wave lesbian feminism as desexualizing lesbian identity in favor of a political definition (“Any woman can be a lesbian,” sang lesbian separatist folk musician Alix Dobkin in 1974). Riffing on the politics of the 1970s, if not antagonistically, then at least with irreverence, On Our Backs appropriated their title from off our backs, a well-known feminist newspaper with roots in the women’s liberation movement. A series of images that Christopher produced for On Our Backs in 1992 announced a fetish for flannel. Christopher admits—with, one suspects, tongue firmly in cheek—to having suppressed her desire for the unfashionable check until seeing a documentary about Olivia Records, a record label synonymous with 1970s lesbian feminism. Getting off on history indicates a less complete break with the past than the idea of feminist waves first implied.

Tessa Boffin, The Angel, 1990, from the series The Knight’s Move

© the Estate of Tessa Boffins/Gupta+Singh Archives

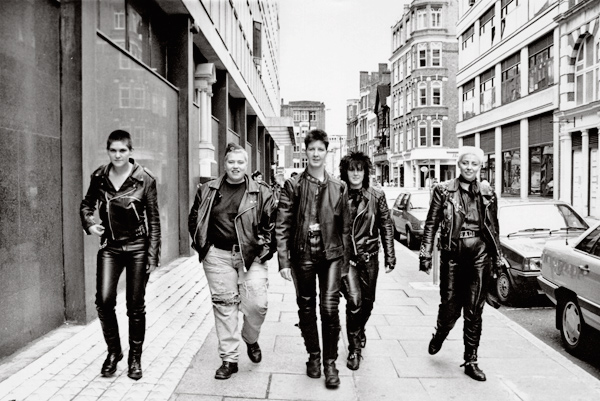

On Our Backs also looked back to public sex cultures that emerged in the wake of gay liberation. Many photographers whose work appeared in the magazine subverted the visual language of the male-dominated BDSM community. Gwenwald’s fetish pictures, including a piece of lace reminiscent of a handkerchief or panties folded into a back pocket, offer a wry counterpoint to Hal Fischer’s record of homosexual dress codes collected in his book Gay Semiotics (1977). Christopher acknowledges the formal influence of Robert Mapplethorpe on her approach to visualizing lesbian sex and desire. But, however exciting it might be to consider this subversion of gay male culture, references to canonical figures like Mapplethorpe should not obscure the radical project pursued by Christopher, Gwenwald, and their colleagues. As the AIDS crisis took hold in the United States and elsewhere, the imperative to create publicly visible representations of queer sex became ever more vital. In the context of political disempowerment and medical crisis, lesbian sex photography would take on increasing political charge, as the magazine provided an essential platform for lesbian creativity during a regime of state censorship enacted during the period of the culture wars in the United States. Circulating in unmarked envelopes, On Our Backs networked lesbians internationally. An exchange took place between photographers in the U.S. and the U.K., where figures like Del LaGrace Volcano, Tessa Boffin, and Jean Fraser foregrounded lesbian identity within the theories of representation emerging out of schools such as the Polytechnic of Central London. If this was photography in the service of pleasure, it was also photography in the service of history. To engage in documenting lesbian sex in the 1980s was to advance the historically necessary claims of feminism and gay liberation into the public sphere. For example, Mostovoy’s images of lesbian sex workers at San Francisco’s Market Street Cinema might be viewed as part of a broader reworking of documentary practice in the 1980s, tied to the emergent debates around the politics of representation. Yet many lesbian practitioners regarded documentary with suspicion. Instead, pornography, which is peculiarly structured by both arch realism and pure fantasy, provided a space where the pathologization of lesbian sexuality could be resisted. For its ubiquity, its obscenity, perhaps even the material conditions of its production, pornography is a particularly degraded kind of image making in histories of photography, removed from the value systems of the academy as well as those of the art world.

Del LaGrace Volcano, On the Way There, London, 1988

© the artist

A collective project like a magazine is bound to be fraught with internal struggles, and from the outset On Our Backs lived with a degree of financial precarity that would lead to both a hiatus and change in management in the mid-1990s. The difficulty of running the publication was compounded by the mounting restrictions on queer spaces as moral hysteria surrounding the AIDS crisis intersected with pernicious gentrification in San Francisco, which had a homogenizing effect on the city. Revisiting this era through the pages of the magazine allows a different set of possibilities relating to queer identity to emerge. On Our Backs is but one chapter in a rich history that also includes the work of Cathy Cade, Ruth Mountaingrove, Corinne, and Volcano, whose vital contributions to queer photography began in the lesbian bars of San Francisco in the early 1980s. Trans or intersex-identified photographers like Volcano and Mostovoy started in the dyke scene alongside writers like Patrick Califia, known for his groundbreaking writing on BDSM subcultures and trans politics. Held within lesbian sex cultures of the 1980s are the kernels of the ongoing struggles for recognition—of trans folk, sex workers, fat activists—that continue to unsettle feminism today. At times it seems the magazine presents us with a lesbian feminist history of queer photography; at others, a queer history of lesbian feminist photography. Perhaps instead, the diverse record of lesbian desire produced through the photographs in On Our Backs shows us that the two are yoked together, far harder to separate than existing histories might have us believe.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.