South Africa in Black and White

In David Goldblatt’s photographs from apartheid to the present, a striking account of South African life.

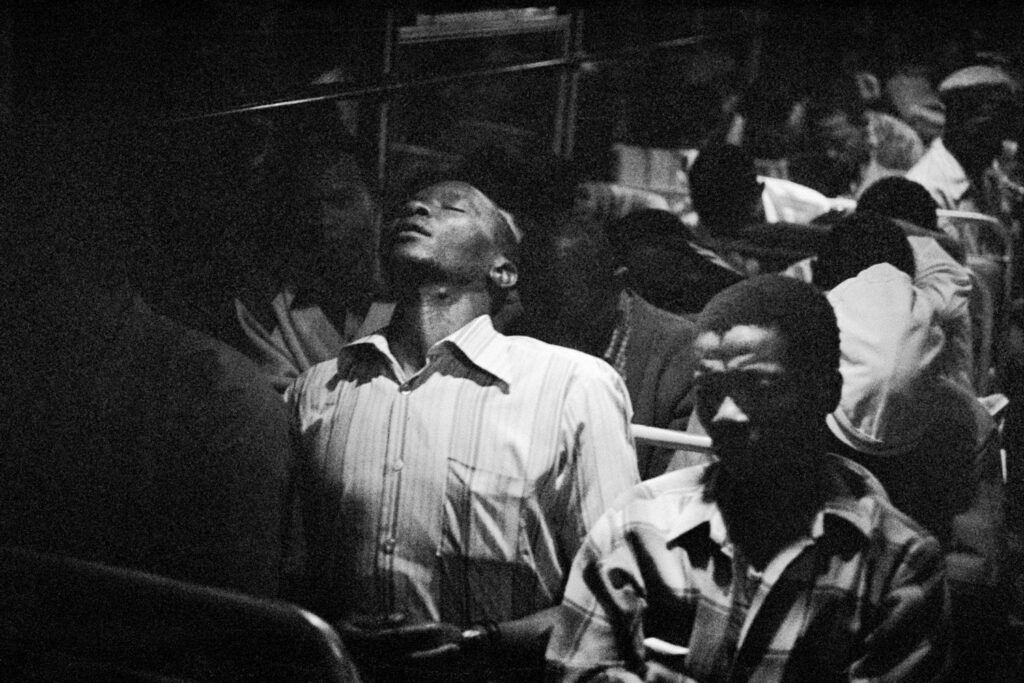

David Goldblatt, AM/PM. Travelers from KwaNdebele buying their weekly season tickets at the PUTCO depot in Pretoria, 1983

David Goldblatt is relentless. A titan among photographers who chronicled South Africa during and after the Apartheid years, Goldblatt began his career in the 1960s by shooting for newsmagazines and the Anglo American mining company. He later gravitated toward landscape and the built environment, from the farmlands, to the Johannesburg suburbs, to prim Cape Dutch homes. Goldblatt’s trenchant account of 1970s-era, middle-class white privilege in the 1982 book In Boksburg is a sobering counterpoint to the politically inflected photojournalism of the time, in which incendiary racial conflicts portrayed South Africa in a state of endless crisis. Now in his eighties, Goldblatt—whose many photobooks, including In Boksburg, are being lavishly republished by Steidl—has found a smooth trajectory into the contemporary art market through international group and solo exhibitions.

For his debut at Pace/MacGill, Goldblatt juxtaposes two series created thirty years apart. One, The Transported of KwaNdebele: A South African Odyssey (1983–84) is vintage Goldblatt, made under the cover of night amid cramped interiors and gloomy depots. The Transported offers a grainy account of coach buses taking workers to the Marabastad terminal in Pretoria and back to the “Bantustans”—reserved “homelands” for blacks—over two hours away. The other, Ex-Offenders at the Scene of the Crime (2008–15) depicts former criminals and features detailed personal narratives, based on Goldblatt’s interviews, installed on placards jutting from the wall.

Goldblatt has said that he is not an artist but, then, as he reminds the viewer here, he’s not exactly a journalist either. As a result, he notes, his “allegiance is to no one other than my subjects and myself.” Even so, he came to international recognition by capturing the effects of life under a repressive state and attended to such images with lengthy, detailed captions. In The Transported, the meandering buses, crowded with men exhausted from the day’s work or their journey from the night before, were integral to a state that kept whites separate from everyone else but relied, nonetheless, on the cheap labor of black and other, mixed-race populations.

Goldblatt represents this complexity with precision and economy in modest, 10-by-16-inch prints, as in a photograph titled 9:00 pm. Going home: Marabastad-Waterval bus: For most of the people in this bus the cycle will start again tomorrow between 2:00 and 3:00 am (1983). In this now-iconic photograph, soft lighting haloes a congested aisle and recedes into the distance, while a man in the foreground cranes his head back and steals a few moments of rest. The title says it all, with clinical precision; so do captions noting bumpy roads or standing room for twenty-nine riders. As a white photographer, of course, Goldblatt surveyed such scenes with a degree of detachment unavailable to his notable black contemporaries, such as Peter Magubane and Santu Mofokeng. Still, Goldblatt’s images, which are not portraits as such, vividly track overlooked moments in everyday life under a regime that controlled not only a person’s space, but also his or her time.

A similar investigative logic is at work in Ex-Offenders, but in this more recent work Goldblatt achieves a previously unseen level of poignancy—even rough beauty. These larger prints, tonally dense and rich in detail, show his technical prowess. Dialing in on the sitters’ wary faces, they are also his most startling portraits to date, as in Adellah Snape on the Hagley Road, Birmingham where she worked as a prostitute, 13 September 2014. Snape, a seemingly ordinary woman, is transfixing, as she gazes squarely from the frame. For the series, Goldblatt contacted ex-offenders through prison rehabilitation organizations and paid his subjects 800 South African rand (approximately fifty-eight dollars) for a photograph and an interview at the scenes of their crimes. These banal locations, Darling Street in downtown Cape Town, or the banks of the Thames River—in 2012, he extended the project to England—draw the figures into otherworldly depths of emotion, and remain consistent with Goldblatt’s longtime interest in physical sites of violence and trauma.

All photographs © the artist and courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

While Goldblatt remains committed to the power of place—the “structure of things” in society—Ex-Offenders suggests an intergenerational dialogue with younger photographers. Goldblatt founded the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg in 1989, and the bracing portraiture of such alumni as Zanele Muholi, Sabelo Mlangeni, and the late Thabiso Sekgala, to name a few, echos Goldblatt’s precise balance between banality and intensity, but commits more fully to portraiture as a means of framing postapartheid South Africa. The calm empathy of Ex-Offenders shows that, even now, Goldblatt’s practice continues to evolve—and to provoke, though images, the resonant questions he asks of his viewers: “Could they be my children or grandchildren? Are they you or me? How did they come to do this? What are their lives?”

David Goldblatt is on view at Pace/MacGill in New York through October 29, 2016.