Southern Futures

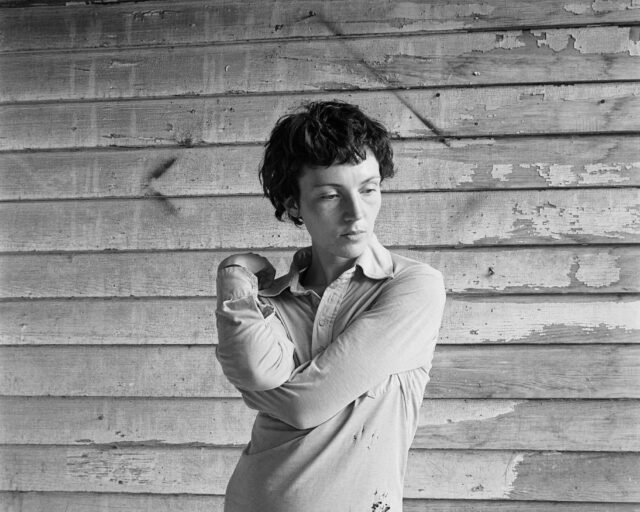

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

The most recent iteration of the High Museum of Art’s Picturing the South series features the work of Mark Steinmetz, originally from Athens, Georgia, who focused his project on Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. In one of the world’s most heavily trafficked airports, Steinmetz explores the paradox of the space as the crossroads of Southern identity, both in the mainstream and on the periphery. The sixty hazy, black-and-white photographs featured in the exhibition imagine the South in a new light, and ask questions about the future of southern photography. I recently spoke with Gregory Harris, the High Museum’s assistant curator of photography, about the show.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Izzy Leung: Can you tell us about the history behind the Picturing the South series?

Gregory Harris: The Picturing the South project was initiated in 1996 to coincide with a major survey of southern photography in order to bring some new, fresh work into the exhibition. The first artists commissioned were Sally Mann, Dawoud Bey, and Alex Webb, and the the project has continued to roll from there. The South has had a fairly significant role in the history of photography, with the photographs that Walker Evans and William Christenberry both made in Hale County, Alabama, the photography of the civil rights movement, being some notable examples. At the High, we try to emphasize the South’s place within the history of photography as a subject that has been compelling to people who are natives of the region, but also for people from other parts of the country and the world. The commissions are a way we can add to that ongoing conversation.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: So, in order to properly picture the South, why did the High Museum choose photography, rather than a different medium?

Harris: Photography may not seem like an obvious answer, but I can’t think of a medium that’s better suited for telling stories and representing the region. A lot of the work that has come out of this commission has been documentary in nature. Richard Misrach’s long-term examination of “Cancer Alley” along the Mississippi River is a great example. There have been some artists who have taken a more experimental approach, like Sally Mann, who started seriously investing in the collodion process in relation to the Southern landscape. Abelardo Morell made pictures using mirrors and frames set in some of the natural environs around Atlanta. But, for the most part, it’s been a representational documentary project. Photography gives artists a way to articulate a distinct vision and a distinct approach to whatever subject matter they happen to be dealing with.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2012

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: How are Mark Steinmetz’s images representative of the South? What about the Atlanta airport conveys something greater about the South?

Harris: Mark’s pictures position Atlanta as a global hub. The Atlanta airport is the busiest airport in the world—you can get basically anywhere from Atlanta. By digging into that idea, he’s looking at a contemporary South that is a player on a global stage. Between the music, film, and art scenes, which are all definitely becoming more robust, Atlanta has developed an outsized cultural presence. Despite the fact that it’s a relatively small city, Atlanta is a major hub for a lot of activity on a national and global scale, and the airport is in some ways a mechanism and also a metaphor for that activity. Mark presents the airport as a paradox, contrasting the human-made with the natural world, the public with the private. That kind of complexity and contradiction are emblematic of a region as large and varied as the South.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: The title of Steinmetz’s series, Terminus (2018), positions the city as the end of the line or the terminating point, yet, as you said, maintains Atlanta as an intersection of culture and transit. How do you think the word terminus fits into the vision of his project and the cultural history of Atlanta at large?

Harris: Terminus comes from the original name of the city when it was built at the intersection of two railroad lines. Since its founding in the 1830s, Atlanta has been this intersection for various kinds of transportation, moving people and goods around the region and country.

One of the things that interested Mark about the airport is that it is a liminal place where people are leaving one place behind and going off to another. Thinking more broadly or metaphorically, they could be leaving one chapter of their life behind and starting off on a new adventure. A lot of Mark’s work looks at people and places on the margins of the mainstream, and the edges of cities. He takes a lot of pictures on the road, particularly on highways. The highway becomes a metaphor for transition and a way of expressing a longing for something. The airport fits in perfectly—it is literally at the edge of the city; it’s something that despite its size and how busy it is, it’s still peripheral to our everyday thinking. The airport is so outside normal, everyday life for many people that they have a different kind of experience in the airport. In the pictures that Mark took of people, they’re almost completely lost in thought, often alone, or if they’re near other people, they are gazing out a window, or looking at their phone. They are lost in their own world, disconnected and lost in contemplation.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: When Mark was taking the photographs, was he in the midst of traveling, or did he make special trips to shoot?

Harris: For the most part, Mark made the photographs during his normal travel. He would arrive at the airport early or stay late after a flight and make pictures while he was waiting. He also didn’t get any special access for anything he was shooting. There are no pictures of security checkpoints or behind-the-scenes areas. Everything he photographed is open and accessible to the public. He didn’t make many special trips, with the exception of the times he went to shoot in the neighborhood at the edges of the airport that are completely overgrown by kudzu and trees. There are also several pictures he made at night from a hotel that is located along the runway. He would get a room that overlooked the runways, set up a tripod, and make long-exposure pictures of the planes taking off and landing.

Mark tends to make his work wherever he happens to be, and out of whatever is happening around him. There’s no staging or setup—it’s intuitive and improvised. He’s very much an old-school photographer in that vein.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: What can we expect to see from the next two Picturing the South exhibitions, featuring Debbie Caffery and Alex Harris?

Harris: Those commissions are both still ongoing. Debbie is pretty close to completing her commission. She photographed agricultural communities in the Mississippi Delta that, over the last twenty to thirty years, have rapidly been losing population as the economies have shifted and people have moved into urban centers. Debbie’s work is very emotionally charged and evocative. She shoots in black and white and has an amazing sense of light and tonality that creates a mood that give the pictures an edge.

Alex Harris has been photographing on independent film sets throughout the South. He is really interested in how the South is portrayed in cinema. He was the set photographer for Steven Soderbergh’s film about Che Guevara and that sparked his interest in shooting on film sets. Alex has been photographing in ways that reveal the artifice of the production while also photographing the scenes themselves as they’re being acted out in such a way that you might never know he was on a film set. Some of these pictures clearly have a melodramatic quality that almost look like a Jeff Wall. It’s clear that something is being played up for an audience of one kind or another. The ways that he’s playing with narrative and artifice is really exciting.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: The two upcoming photographers are distinctly from the South, whereas previously commissioned photographers, such as Martin Parr, Richard Misrach, and Alex Webb, are not. How does this change the project?

Harris: There had been a lot of discussion amongst the photography community here in Atlanta, in which people asked, “Why have there not been more southern photographers who have received this commission? Why aren’t we celebrating and highlighting the talent that is here in the region?” So with this group, there was a conscious choice made to commission artists who are from the South. But, historically, our curators have used the projects as a way to collaborate with some of the most prominent and promising contemporary photographers and give them an avenue to create new bodies of work and try out something new, whether that’s a new process or a new subject. The commission is a way to open up possibilities and present opportunities for artists to engage with the southern landscape and culture.

I think one of the things that the High’s photography program has done really well over the years is to look closely at the South, but to do so in a way that isn’t provincial. We show work from all over the country and across the world, and place that in conversation with the unique, complicated history and culture that is characteristic of the South. To embrace the region, but not at the expense of everything else that is going on in the wider world.

Mark Steinmetz: Terminus is on view at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, through June 3, 2018.