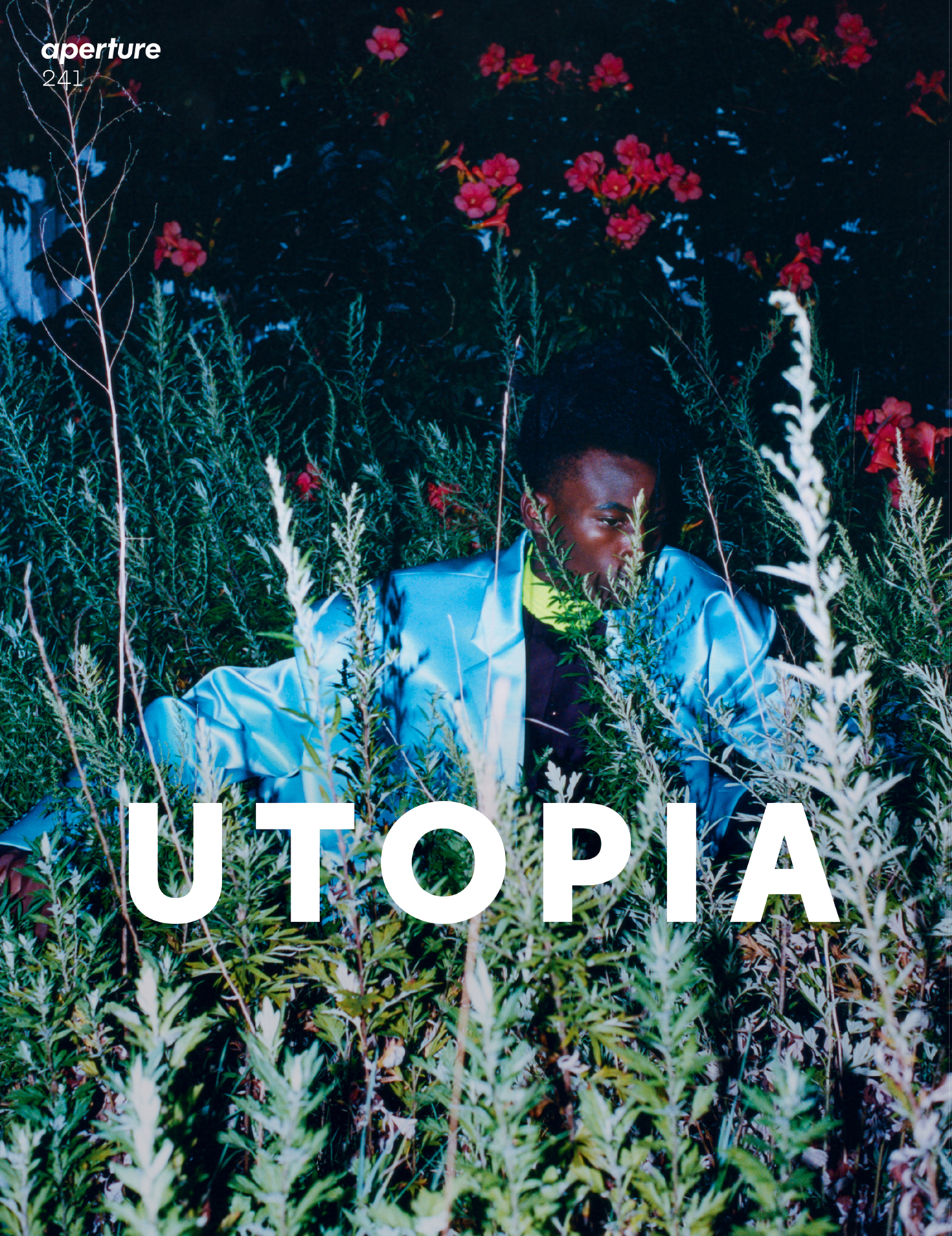

The Counterculture Collective Who Wanted to Save the Earth

Matt Wolf’s new documentary about the Biosphere 2 experiment in Arizona shows the uneasy relationship between capitalism, utopia, and reality television.

For more than a decade, the filmmaker Matt Wolf has won acclaim for his meticulously crafted documentaries that reveal lost histories through deep dives into media archives. His focus is often on radical outsiders whose projects range from the quixotic to the paranoiac. His first film, Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell (2008), is an exploration of the life and work of an avant-garde cellist and disco producer, while Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project (2019) examines the fascinating obsession of its subject, who recorded live television news continuously from 1979 until her death in 2012.

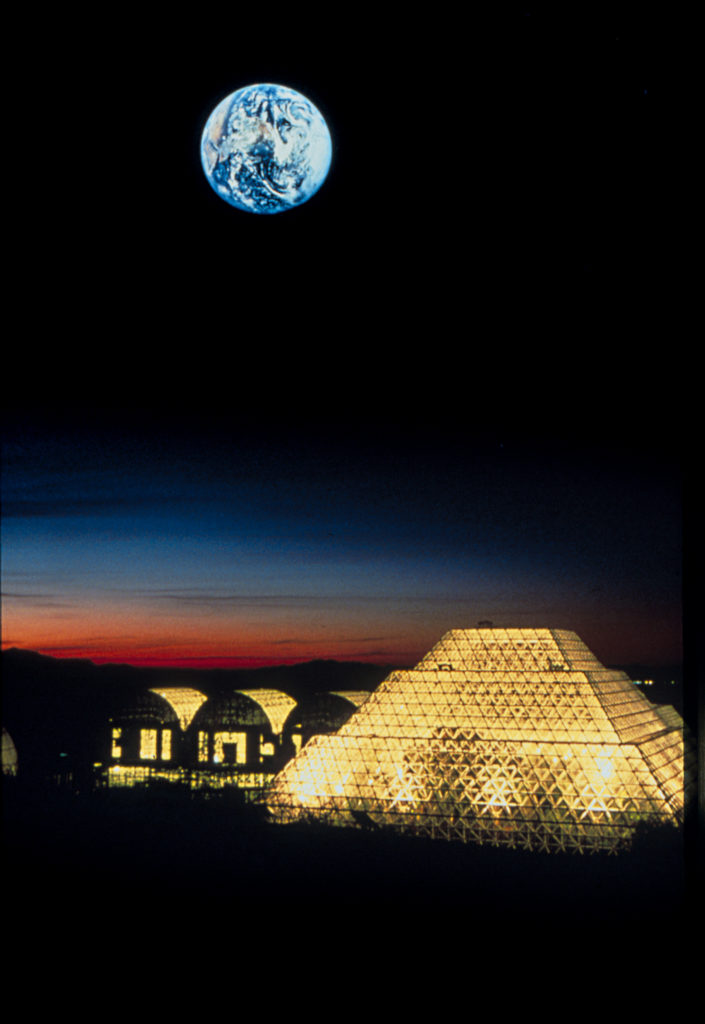

Wolf’s latest film, Spaceship Earth (2020), traces the activities of a counterculture collective known as the Synergists from the 1969 founding of a sustainable ranch in New Mexico through the 1991 launch of Biosphere 2, a staggeringly ambitious attempt to pave the way for human life on Mars and to learn about how to live more sustainably on Earth by building a completely self-enclosed ecosystem inside a glass pyramid in the Arizona desert. Last summer, Wolf spoke to the architect and critic Julian Rose about the uncanny resonance of the Synergists’ efforts to give form to the future.

Julian Rose: One of the fascinating things about Spaceship Earth is that the protagonists were obsessively documenting their own work as it progressed, producing countless hours of film and video that captured the projects they pursued. How did you first become aware of all that archival material, and how did your film evolve out of it?

Matt Wolf: My creative process involves searching for archives because I’m drawn toward hidden histories. Most of the preliminary research I do begins on the Internet. In this case, I came across these striking images of eight people in bright-red jumpsuits, looking like the band Devo, standing in front of a glowing glass pyramid, and I genuinely thought they were stills from a ’90s science-fiction film. But I quickly realized that, in fact, this structure was real—it was Biosphere 2—and that those people lived sealed inside of it for two years. And the more I looked into the history of the project, the more byzantine the story became. I learned that it had been the brainchild of this countercultural group called the Synergists, and I went to their commune-ranch in New Mexico called Synergia Ranch. When I arrived, I was brought into this temperature-controlled closet that had hundreds of 16mm films and analog videotapes and thousands of images. I learned that this group had been documenting their activity for nearly half a century, and that the material had never been used or seen.

Rose: The term archival usually suggests material that’s raw or unprocessed, but when I watched the film, I was struck by how highly authored, even artistic, much of the footage is—some of it looks like it could be experimental film or video art. Did that level of authorship complicate your own role as a filmmaker?

Wolf: My filmmaking involves working with personal archives—personal in the sense that they are outside established institutions or are even anti-institutional. I’m often looking at people who pursued complex and multifaceted projects, and they didn’t necessarily represent and explain those projects in ways that were accessible. I want to reappraise their legacies and act as a translator, helping to find the logic and coherence and vision behind this idiosyncratic activity, and to explore how it is often incredibly relevant to the broader world. For this film, the archival footage was literally shot from the perspective of my subjects, so I had a unique opportunity to visually translate their story beyond the flattened coverage in the news media.

Rose: There’s a fascinating tension that emerges between the footage shot by the subjects themselves and all the contemporary media coverage that you have woven into the film. At the time of the original experiment, Biosphere 2 was widely regarded as a spectacular failure, largely because of the way it was covered in the media. There were tremendous controversies about various technical problems and the ways they were solved—questions about secretly bringing materials into the structure and even pumping oxygen inside.

Do you think the project was seen as a failure because the vision it presented was too radical, too utopian, or simply because the Synergists couldn’t navigate the transition from their own personal documentation of the project to its depiction in the mass media?

Wolf: Well, there are two prongs to that question, one dealing with utopia and one dealing with the media’s impact on the project. The Synergists actually rejected the idea of utopia, primarily because it has historically been so associated with the imaginary and the impractical with failure. In his autobiography, John Allen, who coalesced the group, expresses how, in so many senses, the Synergists tried to create a place that doesn’t yet exist. So what I would say is that the underlying impulse behind this group was futurist rather than utopian.

Rose: But then that vision of the future couldn’t handle all the attention it attracted? The ethos of the project didn’t seem to survive translation into a kind of media spectacle.

Wolf: The title Spaceship Earth is a nod to the theatricality of the project as well as its ambitions. It’s obviously a reference to Buckminster Fuller’s seminal counterculture book, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1969). Fuller was hugely influential for the Synergists. But it is also a nod to the Epcot amusement-park ride called Spaceship Earth, which is a kind of cartoonish sci-fi architecture with animatronic vignettes that depict progress and the future. Biosphere 2 was really this potent mix of countercultural sustainability and theme-park theatrics.

When you pursue a project as ambitious and big as Biosphere 2, it’s inevitable that it is going to attract attention. It became a real mainstream, pop-culture phenomenon. I don’t think this group was equipped with the public-relations skills to manage that. And the experimental dimension of the project, with the eight inhabitants, called the Biospherians, sealed inside of the structure for two years, also stoked the voyeuristic tendencies of the public that later found their expression in reality television shows such as Big Brother and The Real World, and ultimately, of course, Survivor. You can’t separate the way Biosphere 2 was treated in the media from those broader cultural trends. In fact, when The Real World was released, in 1992, the New York Times even called it something like “MTV’s answer to Biosphere 2.”

Rose: Visually, the physical structure of Biosphere 2 is absolutely stunning— this vast, futuristic complex of crystalline glass prisms rising up out of the empty desert. But was the architecture part of the problem precisely because it was so spectacular, so monumental, and so symbolic? You have some beautiful passages in your interviews with the Synergists where they talk about Fuller’s key architectural invention, the geodesic dome, as a perfect model for their group because the struts individually are very light and not very strong, but you put them together and they become incredibly powerful—the sum is greater than the parts. The symbolism is almost too good.

Wolf: That’s like the motto of this film: the symbolism is almost too good.

Rose: A great subtitle if it’s not too late! But you see where I’m going. Did the architecture place an impossible burden on the project?

Wolf: There is a kind of Emerald City aspect to the complex, but I don’t think it’s all theatrical, or that it’s responsible for the demise of the project. I find the architecture to be inspiring and bizarre and futuristic and speculative in terms of science fiction. To me, the aesthetics of it is what makes the project magnificent. That’s one of the words that Linda Leigh, one of the Biospherians, uses. Part of the Biospherians’ perspective is that they fell in love with the biosphere that they had created. There is an intoxicating appeal to the architecture as well as the ecological design inside, and if they fall in love with Biosphere 2, it’s instructive in the sense that we all have to fall in love with the biosphere. That’s what needs to happen for us to create a sustainable future.

Rose: I like the rejoinder that an aesthetic dimension is ultimately what makes it an inspiring project, which might suggest a way of rethinking the fate of utopia as a concept in architecture, where it has almost become a bad word. The thinking goes that modernism did not succeed in large part because it had utopian aspirations that were utterly misguided, and that because of those misguided aspirations, the movement has to be rejected wholesale. Modernism set out to transform the world for the better, and instead it left many things the same and made some things much worse. So when you hear someone describe modernism as utopian, that’s almost a coded reference to its failure. But, as your film shows, there is still so much that can be learned from a subtle, contradictory, and complex project—these projects are still worth studying, and we shouldn’t collapse our understanding of them into a binary of success or failure.

Wolf: The kernel of utopian aspiration is meaningful, and we shouldn’t shut down that aspiration because it is an engine of change. I think it’s quite cynical to dismiss the project of utopia wholesale even if it’s historically proven to fail in empirical terms. And again, I think that the architecture of Biosphere 2 did constitute an achievement in many ways. From a technical perspective, it was incredibly sophisticated—it was perhaps the most airtight structure ever built at that time. The architecture of Biosphere 2 is really the ultimate expression of ecotechnics—to use the Synergists’ term for the combination of ecology and technology— because to make it, engineers and ecologists and architects and experts from a wide variety of fields had to work together to create a system that could support life.

Rose: When you mention technology, it makes me think of the uneasy, even paradoxical, relationship between capitalism and utopia. One of the most surprising moments in the film is when you reveal that this massively ambitious ecological research station was funded by a Texas oil billionaire.

Wolf: They were doing a self-financed project that was trying to change the world for the better and make money at the same time. It’s 100 percent the model of Silicon Valley—of “disruption.” It’s the ethos of Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg, of breaking things to make them better. They were doing it before that model existed and was viable.

I can’t tell you whether that was why the project failed; I can only speak to my point of view as the filmmaker. I wanted the film to be a parable about the limitations of this model, of private venture environmentalism. As much as the film honors and celebrates the vision and aspirations of this group, it is a cautionary tale about how radical environmentalism and corporate interests aren’t the best bedfellows. And speaking of symbolism that’s too good to be true—Steve Bannon is the person who facilitated the corporate takeover of Biosphere 2.

Rose: What a twist in the story! When I saw the footage of Bannon giving a press conference outside of the Biosphere 2 building, it certainly did throw the project’s connections with the present into stark relief. And speaking of these contemporary resonances, I have to ask about the idea of colonization. The Synergists and the Biospherians you interview are totally open about the fact that it was originally envisioned as a step toward colonizing Mars. It’s clear that this seemed harmless to them—after all, they’re talking about an uninhabited planet—but we’re in a moment of fundamentally questioning colonial projects of all kinds. Do you think that there is something about the desire to start over by conquering new territory that is inherently flawed? Is the link between utopias and colonies unavoidable, and is that another dark side of the utopian project?

Wolf: I do think there is a postcolonial analysis of Biosphere 2 that needs to be carried out. The project was conceived of and executed by an entirely white crew. This group said that they were undertaking an ecological project or a scientific project, but in so many ways Biosphere 2 ended up replicating certain dynamics of society. It became a model of society in which there were no established politics about decision-making. So John Allen and Margaret Augustine, the Biosphere 2 CEO, sort of de facto became these totalitarian leaders. The whole question of power spiraled out of control.

Rose: There’s a very powerful moment in the film when you’re cutting between footage of tourists visiting the facility soon after the mission began, when the Biospherians were still inside. We see a group of African American students, one of whom looks into the camera and says, “I would like to know what a young Black woman from Brooklyn would do in a biosphere!” I imagine that by this point in the film most contemporary viewers have registered the lack of diversity in the project, but you made an editorial decision to explicitly call it out.

Wolf: In the past few months, as we’re looking really critically at systemic racism, I’ve recognized that ideas about sustainability are intrinsically connected to the need for equity. Racial justice and environmentalism aren’t always seen as intersecting. We can’t sustain a just society unless we restructure things to enhance equity. I think a lot of utopian projects didn’t do that. Even if they aim to live sustainably on Earth or to create sustainable models of design, these projects reify structural power dynamics that are ultimately oppressive.

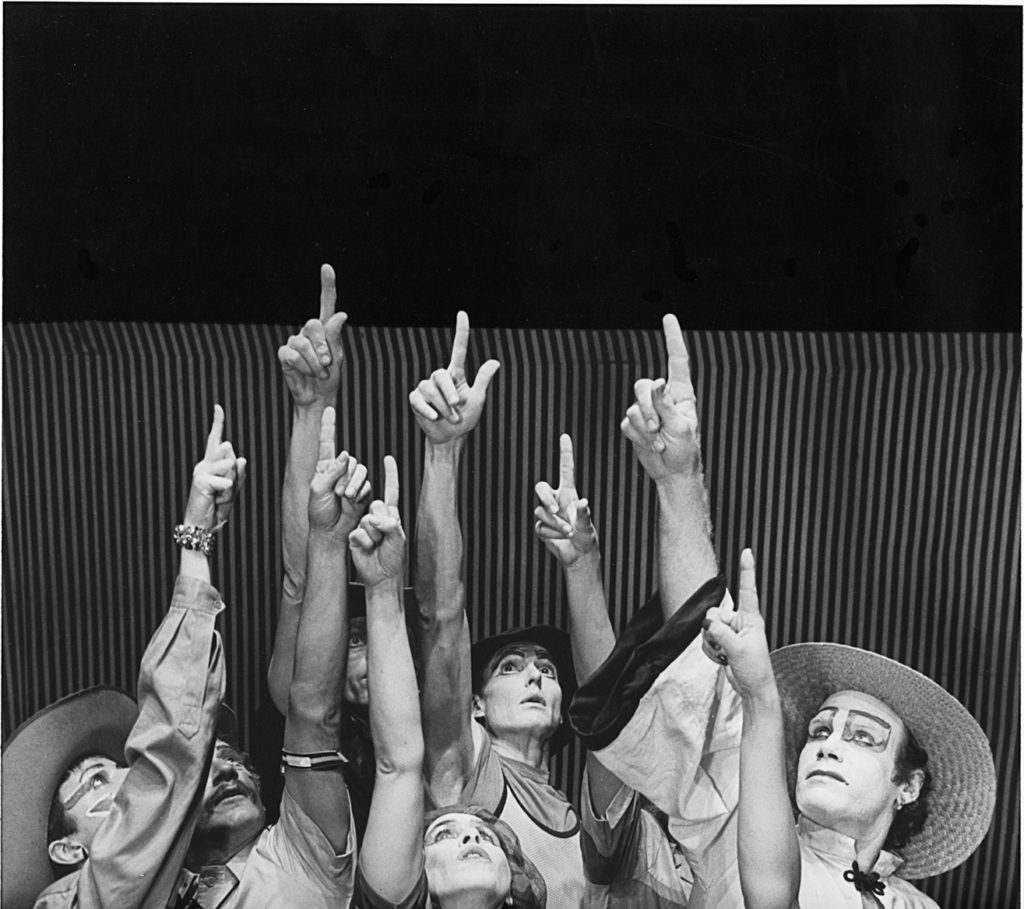

All images from the documentary Spaceship Earth, 2020. Courtesy Matt Wolf

Rose: You could never have planned this, but your film is reaching audiences at a moment when we all feel a little bit like Biospherians. We’ve spent months isolated in these little microcosmic worlds of our homes, where some of us are experiencing the strains of undergoing that experience with small groups of other people, and some of us are experiencing the strains of going through that in isolation and only seeing other people in a mediated way on screens. Has this changed how you see the film? Has it changed your hopes for its impact?

Wolf: It changed the reality of how the film has reached its audience and how it was distributed in the world. In some ways, that’s disappointing to me. I really miss showing films for audiences, communicating with people in real life. In other ways, it was a kind of uncanny opportunity to reach people who were captive at home. As a documentary filmmaker, you’re obviously cognizant of the unexpected, and you always realize that a film you make that’s about the real world can take on an intense new meaning in the future. That’s part of the excitement.

It was quite unusual to make a film that I thought was already prescient because it dealt with issues of ecological catastrophe but then became hyperprescient in the sense that it spoke to the experience we are all going through in quarantine. I don’t necessarily think the film is directly instructive for people about the quarantine, but I do think we can learn from the experience of the Biospherians. The Biospherians, when they left Biosphere 2, all spoke about a feeling of personal transformation. One of them, Mark Nelson, said at the reentry ceremony, “To live in a small world … changes who you are.” They could no longer take anything for granted when they reentered the larger system of planet Earth.

Rose: And you were thinking about how quarantine might have similar lessons about our relationship to the world outside?

Wolf: When the film first came out, at the height of the quarantine, I hoped that the experience would shift people’s consciousness about the environment, would show how we could start thinking about creating lower levels of pollution, about eating food in more sustainable ways—maybe that the transformations we underwent during quarantine would affect how we continue living. But now, thinking about it, perhaps the real transformation is that people are no longer willing to accept the injustices that have existed around us for all of our lives. As a result of being isolated, injustice became intolerable, and this realization broke through the barrier of quarantine so that people went back out into the world to protest. What ended up happening, a month or two after the film came out, was the largest series of civil rights protests in American history. I do think, without a doubt, there’s a correlation between the quarantine and the protests. Because people seem to have gone through an experience of personal transformation in which the way they engage in the outside world had shifted.

Rose: The estrangement of quarantine created enough distance for people to start reevaluating social structures that they might have previously taken for granted.

Wolf: When the world is fucked up by a pandemic, and that actually intervenes in your day-to day life, your consciousness about the fucked-up-ness of the world is really thrown into focus. People are realizing: We don’t want to go back to normal because normal was unjust. So how do we define the new normal? And now, in a way, we’re talking about futurism. And how we’re choosing to reimagine this world is as a new normal that’s more just. That sense of equity is often the missing link in these utopian projects.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “Spaceship Earth.” Read more from the issue, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.