Before They Were Stars

In his new memoir, the critic Douglas Crimp revisits the origins of the Pictures Generation, a fabled era of art, sex, and experimentation.

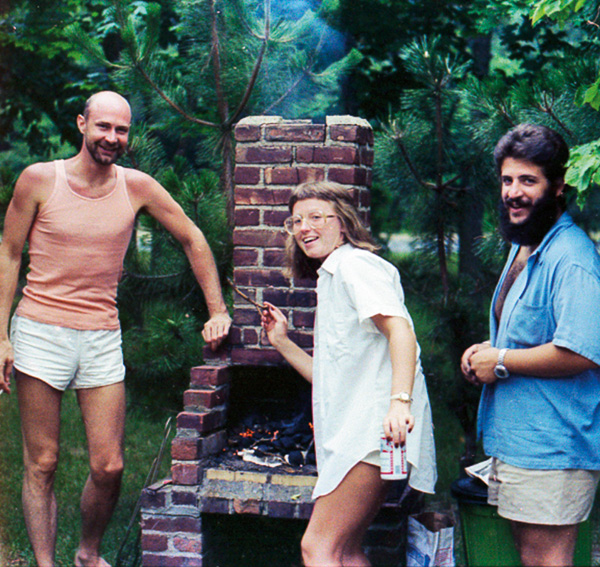

Douglas Crimp with Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo, 1977. Photograph by Helene Winer

Courtesy Douglas Crimp

The canniest thing he did with his milieu-making exhibition Pictures, writes Douglas Crimp in Before Pictures, his new memoir, was to choose a generic title. The 1977 outing at Artists Space in New York featured just five artists. Yet Pictures would come to embody an epochal attitude toward appropriation and mass culture in contemporary art, and absorbed the likes of Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince, who weren’t, in fact, part of the original. By 2009, when Douglas Eklund mounted a survey of the era at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Pictures Artists” was a category and the “Pictures Generation” a brand.

Crimp had something to do with this. In 1979, he rewrote his catalog essay for the poststructurally-inflected journal October, cutting Philip Smith and annexing Sherman, and elaborated his theory of the postmodern. The processes of “quotation, excerptation, framing, and staging,” he declared, had become the predominant sensibility of younger artists “committed to radical innovation.” Forty years on, Crimp’s memoir adds little to what even he calls an “overblown” discourse. Instead, the critic and art historian spends much of Before Pictures fitting that pivotal moment—the decade before the Artists Space exhibition—into a less academic setting.

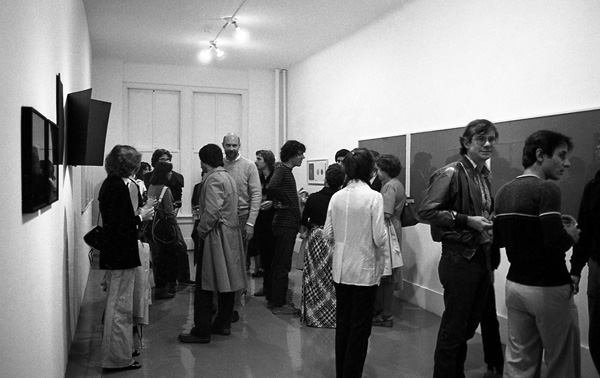

Opening of Pictures at Artists Space, September 1977. Photograph by D. James Dee

Courtesy Artists Space

Crimp’s recollections of his art world and gay world educations, sometimes parallel, sometimes in concert, meander through an idyllically derelict, 1970s New York. The cast is familiar: ArtNews and October, the Flamingo and Max’s Kansas City, Jonas Mekas and Vito Acconci. Yet the book also fuzzes up the willful clarity of formal art history with sometimes awkward, personal asides. Crimp’s mother, for instance, helped him proofread the first Pictures on her front porch. When he revisited the text for October, he was laid up with a broken hip from the roller disco.

As Crimp tells it, his “first job” in the city was as a curatorial assistant at the Guggenheim. He was there when Daniel Buren’s giant striped banner, Peinture/Sculpture, unfurling decisively from the rotunda at the final Guggenheim International in 1971, tweaked the pride of his fellow artists—Dan Flavin called it “drapery”—and so rattled the institution that they took it down before the public opening. (The Guggenheim soon fired Crimp, he suspects, for “knowing too much.”) He writes, with tender self-mockery, “It was a famous museum, one of the most famous, because it had a famous building, one of the most famous, and that made my first job seem glamorous.”

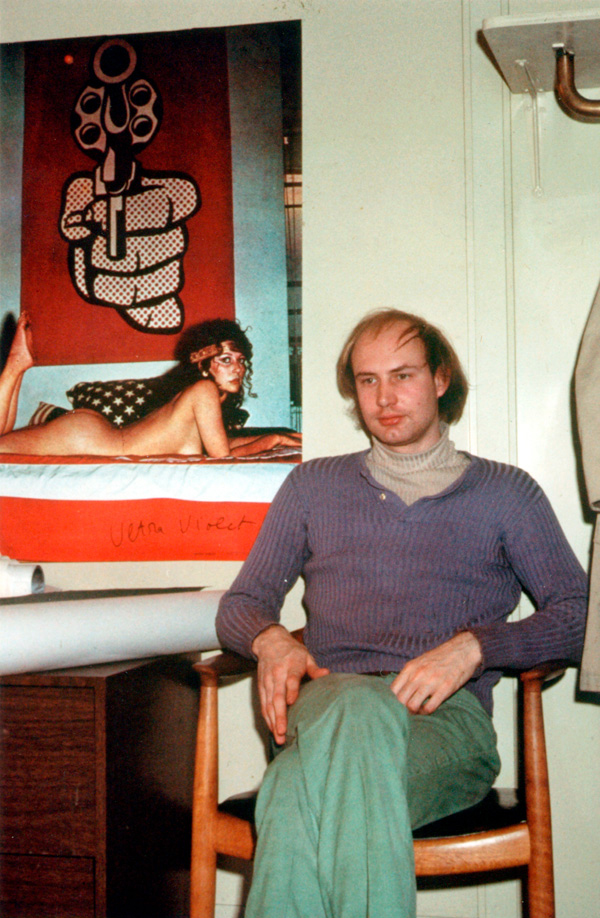

Douglas Crimp in his office at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, ca. 1970

Courtesy Douglas Crimp

Meanwhile, his actual first job was a short stint with the couturier Charles James, “designer of the purple and green evening cape,” who was living in bohemian squalor at the Chelsea Hotel. Crimp ran errands and walked James’s beagle; instead of cash, he was offered payment in credit at Barneys. In 2005, when Buren fitted the Guggenheim’s skylight with green and purple gels for his retrospective, Crimp was ready to call it a vindication of decor. The story reads like a lecture pegged to biography. Illustrating the chapter, and providing its hinge, is a vintage picture of Crimp slumped in a chair in purple sweater and green slacks. (It’s the first of numerous pictures of the author.) Crimp’s account sometimes drags with nostalgia; such well-rehearsed episodes contain the desire for critical politics at museum scale—yet reactivating this desire is another matter. At a tie-in “Before Pictures” exhibition, presently at Galerie Buchholz in Manhattan, Buren’s censored piece appears for the first time since 1971. Its striped square meters sit neatly folded on a plinth.

Douglas Crimp: Before Pictures, New York City 1967–1977. Installation view at Galerie Buchholz, New York, 2016. Photograph by Thomas Müller

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

The choreographer George Balanchine and painter Agnes Martin receive similar analysis. History and plain life coincide; they rarely seem to blend. During the first Watergate hearing, Crimp was glued to a portable transistor radio in a Water Island cabin. He spends several pages recounting the proceedings blow-for-blow, the only reward coming with an account of Nixonites gathered in the basement of the White House watching Tricia’s Wedding, the Cockettes’ camp send-up of Tricia Nixon’s televised wedding.

There are also breezier chapters. One passage details Crimp’s and his Parisian boyfriend’s try at writing a Moroccan cookbook. (Tajin recipe included!) But his more gossipy memories, like a dalliance with Ellsworth Kelly or buying a fridge that belonged to Jasper Johns, feel dutifully wedged between the intellectual debates that Crimp apparently found more compelling. “I resisted disinhibition probably because I was trying to get serious about being an art critic right at the time I became a disco bunny,” he writes. It’s a fair description of himself, and of his approach to writing this memoir, which swerves between the salacious and the cerebral. “I fought the effect of the drugs I took. I thought at the disco.”

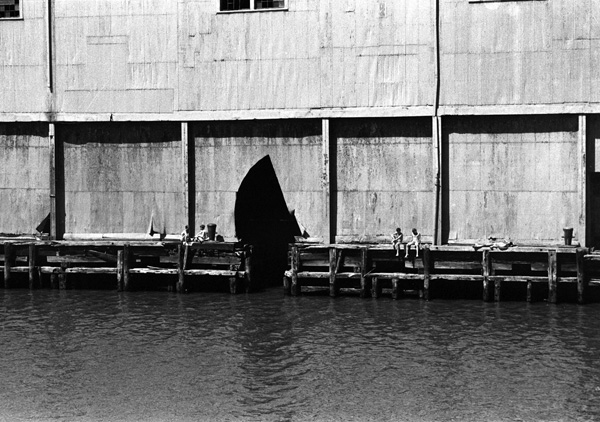

Alvin Baltrop, Untitled, from the series Pier Photographs, 1975–86

© the artist and courtesy the Alvin Baltrop Trust

But where Crimp’s cultural, erotic, and quotidian searches wend through the city itself, his thinking builds on sensation. He spends a few lines reading a couple of Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills through the picturesquely abandoned New York buildings in their backgrounds. His “disco years” in Greenwich Village are marked by the resonance of decidedly avant performance venues with the rituals of barely appointed, underground clubs. Cruising on the West Side piers took him where Gordon Matta-Clark’s sunlit cuts met Alvin Baltrop’s photos of sex acts and sunbathers on collapsing wharfs. Here, Crimp’s almost architectural phrasing strays toward lust:

But the point of cruising, or at least one point of cruising, is feeling yourself alone and anonymous in the city, feeling that the city belongs to you, to you and maybe a chanced-upon someone else like you—at least, like you in your exploration of the empty city. Is there by chance someone else wandering these deserted streets? Might that someone else be on the prowl? Could the two of us find a dark corner where we could get together? Can the city become just ours for this moment?

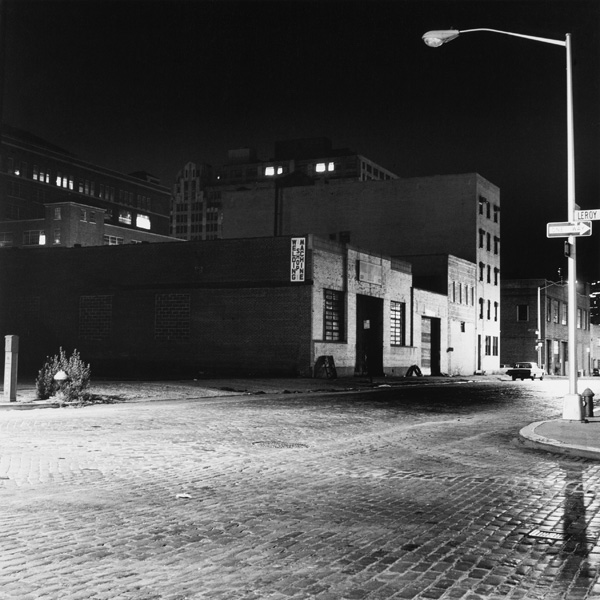

Before Pictures isn’t chronological so much as geographical: Crimp’s interests follow his moves from one neighborhood to the next. Each chapter begins with moody photographs, taken for the book by Zoe Leonard, of the buildings where Crimp lived and the nearby subway stations. When he left the West Village for Tribeca, it was to party less, write more. Once Crimp found an apartment on Nassau Street, where he still lives today, he got down to the work of Pictures.

Peter Hujar, Leroy Street, 1976

© The Peter Hujar Archive LLC and courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The book trails a bit beyond its destination. In the 1980s, as the AIDS crisis gutted the gay world and art world alike, Crimp took up the activism that has defined the rest of his career—figured in 1987 by another October milestone, the special issue he edited on AIDS. New York, too, had changed beyond recognition. In the 1970s, the city was nearing bankruptcy. Today, those streets walked by Crimp and the rest have been redefined by boom. As Crimp writes of Joan Jonas’s 1973 film Songdelay, “We glimpse the city in pieces, in the background, in our peripheral vision—and in recollection.” That is the city “Before Pictures.”

Before Pictures is published by Dancing Foxes Press and the University of Chicago Press. Douglas Crimp: Before Pictures, New York City 1967–1977 is on view at Galerie Buchholz, New York, through October 22, 2016.