Stephen Shore’s American Beauty

Across six decades, Shore has redefined photography—not by picturing life’s deep mysteries, but by capturing something true in the surfaces of the everyday.

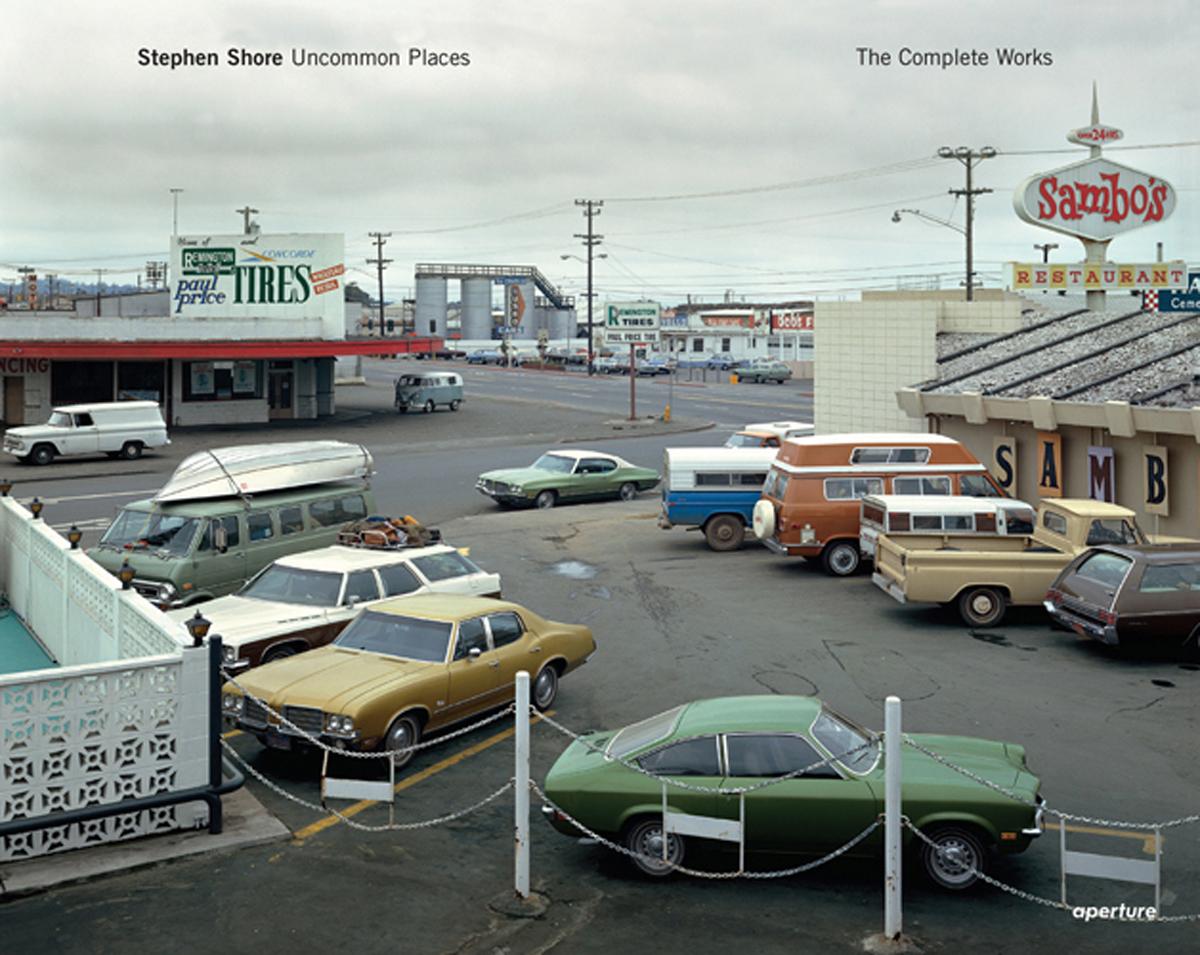

Stephen Shore, Second Street, Ashland, Wisconsin, July 9, 1973, from the series Uncommon Places, 1973–86

Stephen Shore makes remarkable pictures of seemingly unremarkable things: a freeway seen from above, a Texaco gas station, runners on a paved road. His work is consistently a pleasure to look at, especially because it can subvert the conventions of what a photographic composition is, or use a vernacular form uncommon in the art world. Vehicular & Vernacular, an exhibition this summer at the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Paris, reveals these qualities and also offers a moment to reconsider Shore’s output in relation to Pop and Conceptual art.

In 1965, Andy Warhol hired Shore. Instead of pursuing school, the young photographer stayed at the Factory until 1967. In a discussion with Lynne Tillman, Shore once remarked on two things he learned from Warhol: to focus on concepts and to work serially. He took something else from him, too, a certain vulgarity—that is to say, an embrace of common or vernacular forms. If Warhol used silkscreen and film, for example, Shore would use postcards and color photography, then later print-on-demand books and drones.

The earliest work in the exhibition dates from 1969, not long after those so-called Velvet Years in New York. By then, Shore was taking what he had learned at the Factory and applying it to one of his recurring subjects: the complexity of American ways of seeing. One year after he had acquired a copy of Ed Ruscha’s 1966 accordion-format photobook Every Building on the Sunset Strip (and in the same year that Jeff Wall, an artist with whom he shares affinities, was producing Landscape Manual), Shore shot from the backseat window of a car hired by his businessman father as it went from meeting to meeting across Los Angeles. The artist was twenty-one. When he exhibited these photographs, instead of presenting the selection he thought best, he showed all of them in a row. The work was as much about the idea of how to see a city like Los Angeles as it was about any individual image’s value as a picture. The photographs themselves are raw, observational, sometimes cropped at odd angles, sometimes blurry, almost always compelling.

Among other early works on display is Greetings from Amarillo (1971), a playful series of postcards Shore produced of banal buildings and intersections in the eponymous Texas city. On the road the following year, using a simple 33mm camera, he started American Surfaces: quotidian snapshots of people, ads, cars, horizons, a hotel toilet bowl—the sort of thing more likely found in a scrapbook, not a gallery. At nearly the same time as Luigi Ghirri in Italy and William Eggleston in the American South, he decided to print in color, which was then associated with advertising, fashion photography, or family photo albums, not serious art. Perhaps in homage to Warhol, he displayed small-format “drugstore prints” on the wall in grids.

In 1973, Shore switched to a bulky view camera, setting his tripod in front of movie theaters in small towns, motels in the middle of nowhere, gas stations in the heart of Los Angeles. Uncommon Places, which he continued for over a decade, depicts the vastness of North America, from formally sophisticated photographs of a vegetable truck unloading goods in Idaho, to a Hopperesque street in Massachusetts, to a small white chapel against big sky and high mountains in Alberta. American Surfaces and Uncommon Places were both informed, to some degree, by the Factory—curious but detached, conceptual but sensual. Both series, which often included representations of everyday American architecture, led to a collaboration with Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, and Robert Venturi on Signs of Life (1976), an installation recreated in the exhibition, in which floor-to-ceiling images pasted on three walls, complete with a fire hydrant and parking sign, replicate the space of a street.

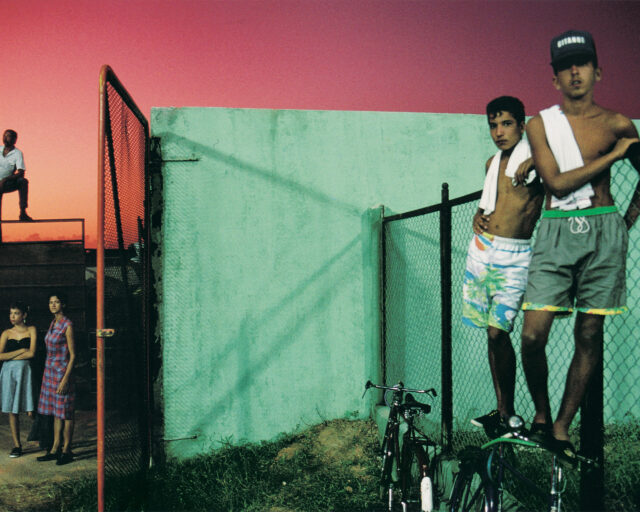

While Vehicular & Vernacular also exhibits Shore’s commercial work for Nike and his print-on-demand photobooks of the early 2000s, both noteworthy inclusions, the next significant series here is the recent one produced with remote-controlled drones. Made during the pandemic, in 2020, these prints present wide horizons, high up from the sky: rows of two-story houses in Hudson, New York; a single white horse dwarfed by perspective in a verdant field in Bozeman, Montana. It’s almost as if Shore is bringing us back, even if only in buried allusion, to that early moment in photographic history when Nadar made his aerial views of Paris from a hot-air balloon. Whether on the ground or from above, Shore’s insistence on using vernacular forms of photography make his work vulgar in the best possible way.

Stephen Shore: Vehicular & Vernacular is on view at Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, through September 15, 2024.