Sunil Gupta’s Vision for a Queer Politics of Belonging

Gupta has spent his career photographing queer subjects in India—and inspired a new generation to insist on making confident, unflinching work.

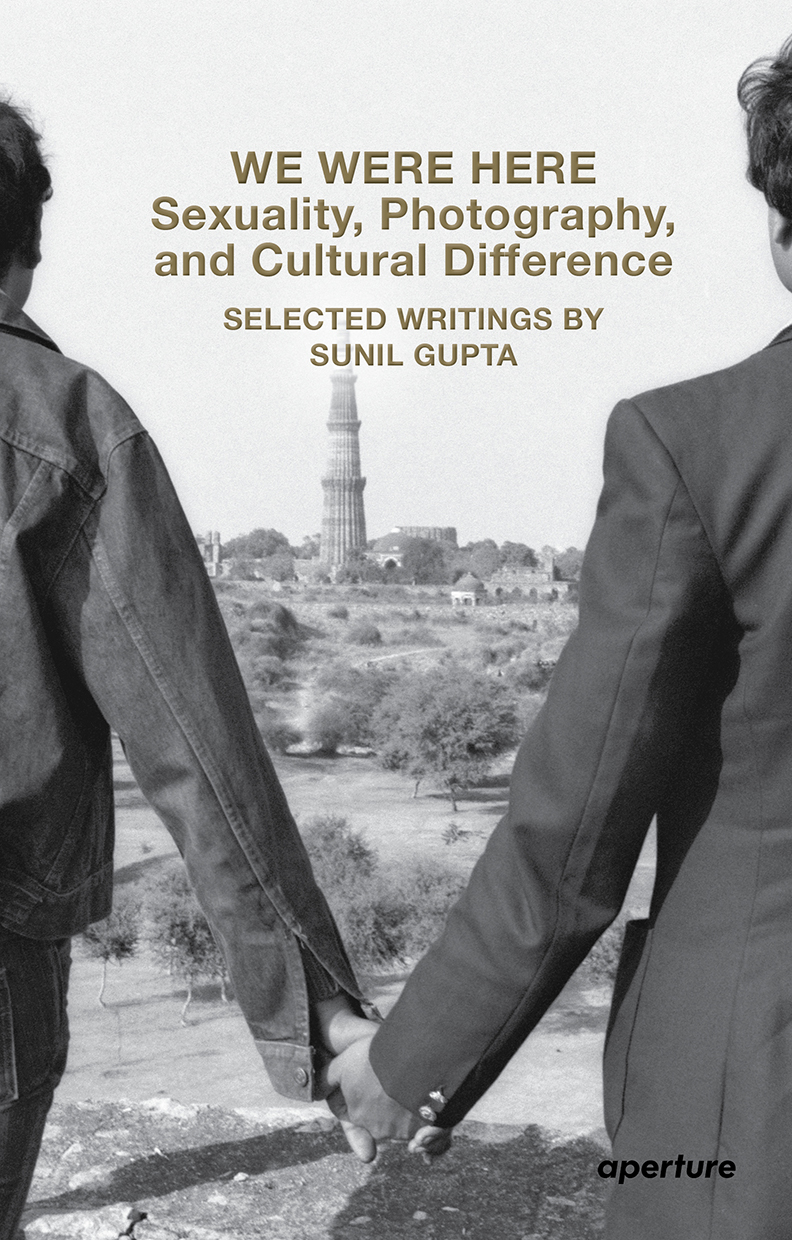

Sunil Gupta, Towards an Indian Gay Image (detail), Qutb Minar 2, 1983

On November 26, 1982, the Guardian, in its Third World Review section, ran a piece with the startling headline “They Dare Not Speak Its Name in Delhi: Sunil Gupta on the Secret Suffering of India’s Homosexual Community.” At the time, being gay in India was still illegal, as decreed by Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, instituted in 1861 during the British rule of India. “One of the best kept secrets in India is the practice of homosexuality, although there is no lack of practitioners from all social classes,” Gupta writes, noting the constant “fear of discovery” and that Indian society “requires the individual to dedicate his/her life to presenting a conventional puritanical public image.” Accompanying the concise text is a single black-and-white image taken by Gupta, picturing a lone man in a kurta, his face cropped from the frame and his body angled away from the camera toward the gardens of the grand Mughal mausoleum Humayun’s Tomb.

Gupta, who was born in New Delhi, immigrated with his family to Canada in 1969, at the age of fifteen. Having aspirations of being a social-justice photographer in the mode of W. Eugene Smith, he traveled back to India in 1980, receiving a student award from Thames Television to document poverty in the rural Ajmer district of Rajasthan. While transiting through Delhi, Gupta, who had come out by the age of seventeen in Montreal, was curious about urban gay life there and wanted to take some pictures. He quickly realized through a friend, the historian Saleem Kidwai, that a gay underground did exist and that to connect with it all that was needed was “one telephone number.” It was “all word of mouth,” Gupta told me last year. “No one wanted to be in a picture.” Gupta was staggered by how men had accommodated themselves to this situation, where it was not polite “in a Delhi drawing room” to discuss living an out gay life. Frustrated, Gupta made some staged photographs that imagined anonymous men purportedly cruising in various locations around Delhi. The image reproduced in the Guardian comes from this group of fewer than ten gelatin-silver prints that, until recently, were rarely exhibited or published, and were later christened as Towards a Gay Indian Image (1982).

Unlike the other bodies of work that Gupta had in his portfolio at the time, either straightforward photojournalism or personal photography projects, these images were conceptually driven. They are constructed photographs, with Delhi not merely a backdrop for the experiences of the gay men Gupta directed but a subject itself. Gupta was aware that gay men navigate a city with a distinct agenda driven by searching for a partner or lover. He marked gardens of historical monuments in Delhi as furtive destinations for these men, who, in those unaccounted hours between when work would end at five o’clock and dinner was served at seven, stepped outside their domestic, conventional family lives to have a casual tryst.

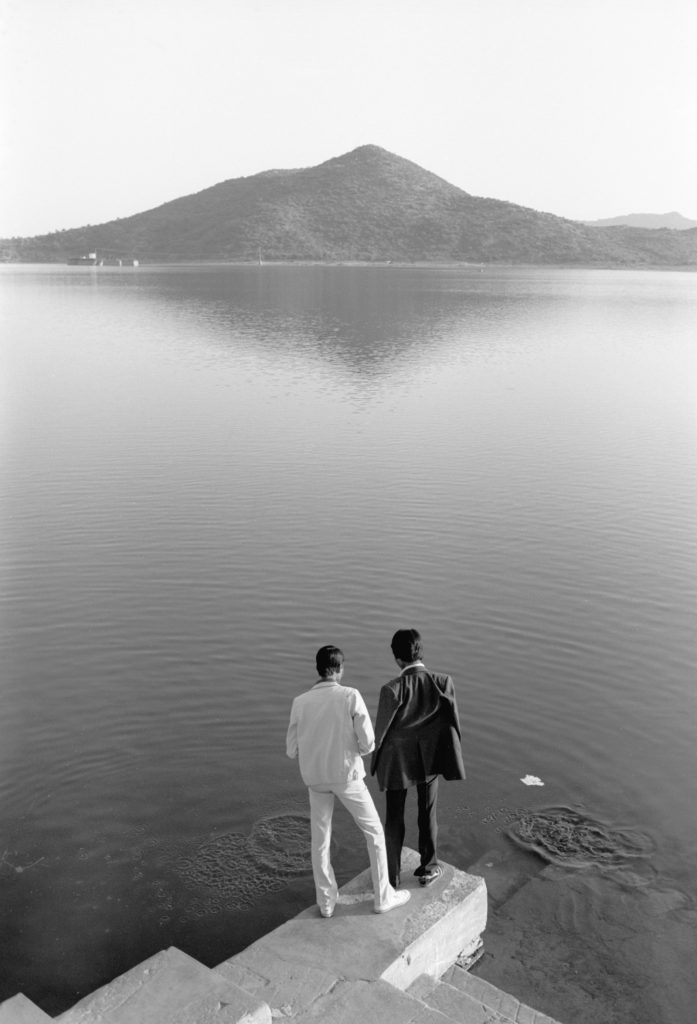

For ethical reasons, Gupta decided against simply taking documentary pictures of men who were actually cruising at these locations, as it was “too revealing of people who did not want to be seen.” Instead, he insisted on the visual presence of historical landmarks, recalling a strain of nineteenth-century colonial photography that exulted in the beauty of archaeological sites often evacuated of people, effectively erasing all indications of the society in which they existed. (A rare documentary image of gay subjects, looking out at a lake, which Gupta made from an elevated vantage point in Udaipur, was later used for the cover of Jeremy Seabrook’s 1998 book, Colonies of the Heart.) By explicitly foregrounding and orienting the bodies of his volunteers, either alone or in pairs, their gazes averted from the camera toward these monuments, Gupta inverts and refutes this historical gesture of erasure, expressly confirming the presence of these men and the culture of cruising that was a part of the fabric of Delhi.

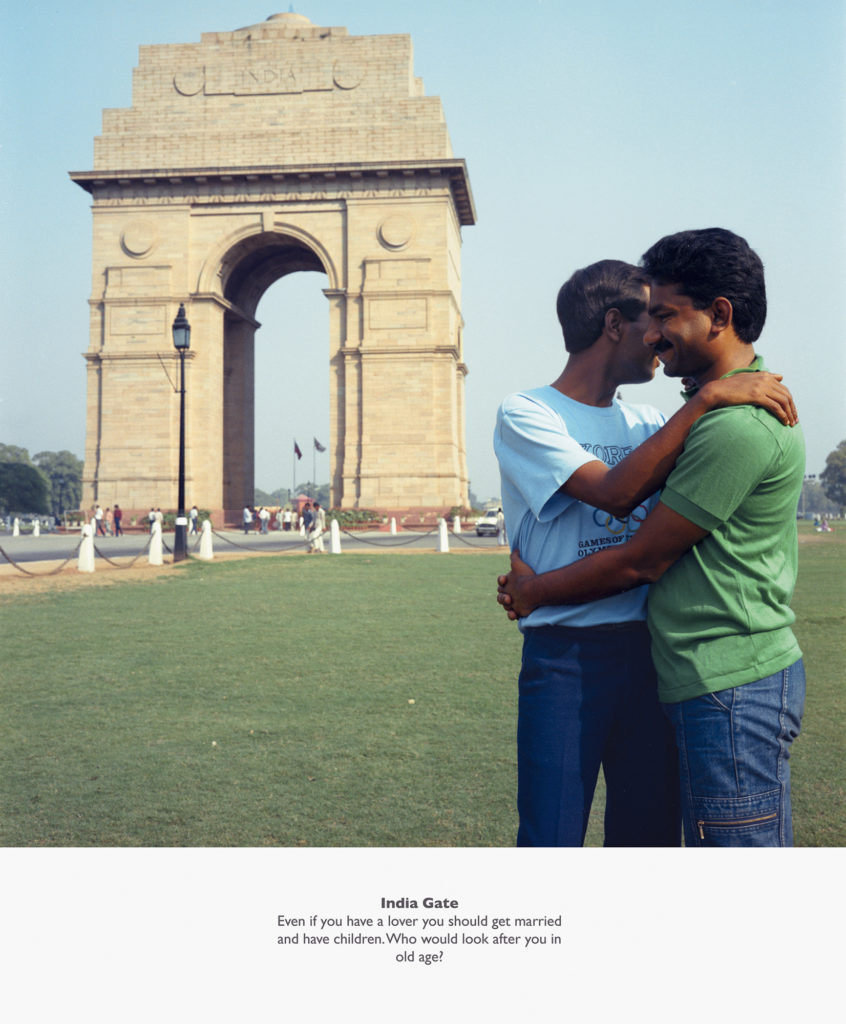

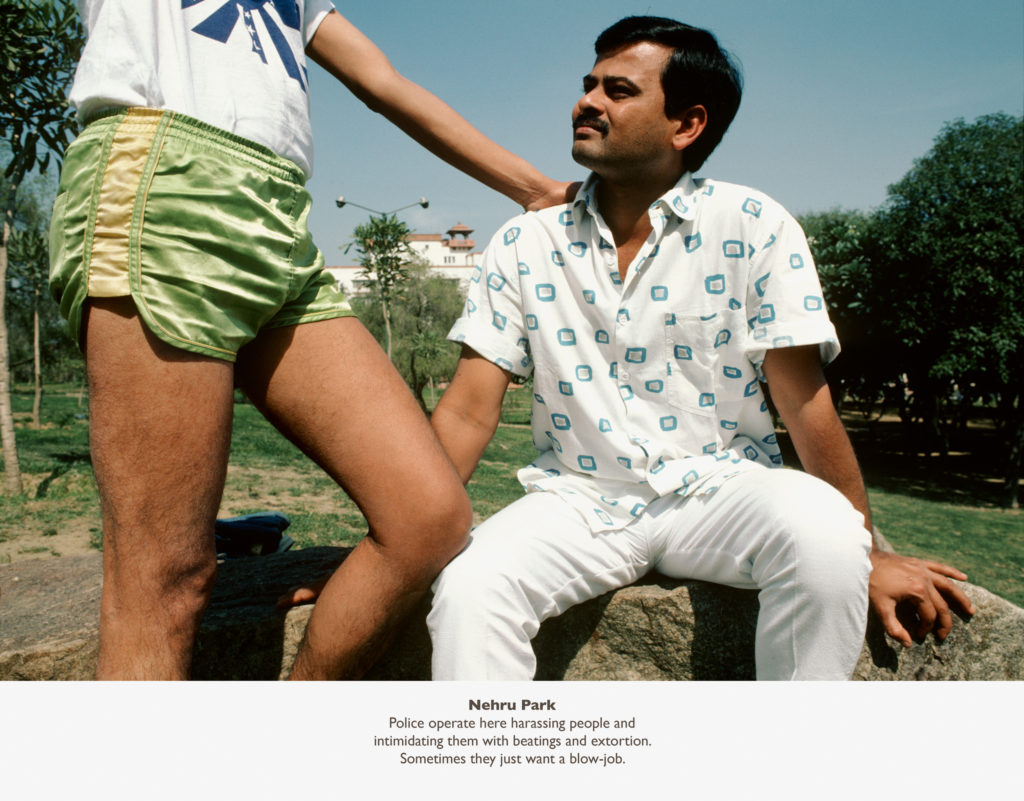

These experimental pictures are the natural precursors to Gupta’s better-known series Exiles, which he shot from 1986 to 1987. Gupta, who was living in London at the time, returned to India to make photographs at cruising sites. He actively tried to involve the men who volunteered as subjects, printing contact sheets in London and sharing them to ensure that he had their consent to print the photographs, with the understanding that the images would not be shown at the time in India. As an art student, Gupta had not seen any representations of gay Indian men in art, as if, he recalled, “there were no gay Indians.” He was not interested in the casual homosocial interactions visible on the streets of the country that the photographer William Gedney sensitively captured during his two trips to India, in 1969 and 1979. “Exiles was about locating Indian cis men in an international gay landscape,” Gupta told me. “I was very keen that my subjects were explicitly gay men, that the images showed such men for the historical record. We were there.”

The geography of Exiles is more expansive: Gupta traversed Delhi, photographing in color. Each image is accompanied by a caption that states the location followed by a few lines from recorded conversations Gupta had with assorted men. The texts do not correspond to the images directly but are drawn instead from disparate thoughts and reflections. One reads, “It must be marvelous for you in the West with your bars, clubs, gay liberation and all that.” Another says, “I am tired of being alone with no prospect of meeting anyone I like. I’m nauseated by the party and park scene.” By contrast, “I love this part of town. It’s got such character and you can have sex just walking in the crowd.” AIDS is mentioned in one caption, but Gupta notes that while there was awareness about the illness in Delhi, “it seemed very distant . . . and everyone thought it was a uniquely American problem”—a situation that was compounded by the Indian Health Ministry’s prolonged public dismissal of the disease.

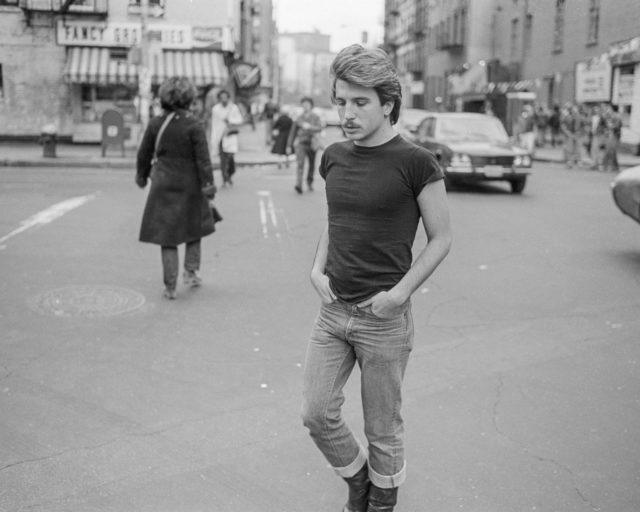

The hesitancies, anxieties, struggles, and curiosities of men in Delhi portrayed in Exiles offer a stark contrast to Gupta’s own personal experiences in the West. A decade earlier, in 1976, Gupta was standing on street corners in downtown New York taking the photographs that now make up his celebrated series Christopher Street. These gay men were, as he says, “dressed up and showing off.” Confidently, they stride by, unabashedly wanting to be seen, their demonstrative sense of self appearing in direct opposition to the faceless protagonists of Exiles. Christopher Street has received a belated adulatory reception, with a 2019 exhibition and an accompanying book.

Work from Exiles was publicly exhibited for the first time in 1987, as part of The Body Politic: Re-Presentations of Sexuality at the Photographers’ Gallery, London. As Gupta describes it, the work just “sank.” Despite the curator’s attempts to be inclusive, there seemed to be no interest in material from beyond the West. Finally, in 2004, Gupta showed Exiles, along with three other bodies of work, in New Delhi, at the India Habitat Centre, as a belated, affirmative homecoming. In the intervening decades, things had begun to change for LGBTQIA Indians: Shortly after Gupta completed Exiles, the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (AIDS Anti-Discrimination Movement, known as ABVA), the first HIV/AIDS activist organization in India, was founded in 1988, in Delhi. In 1991, ABVA published Less Than Gay, a groundbreaking report demanding the repeal of all discriminatory legislation singling out homosexual acts by consenting adults in private, including Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. While the first petition was unsuccessful, throughout the 1990s and into the early twenty-first century, the battle for LGBTQIA rights continued, with the establishment of newer organizations and collectives and with more reporting in the mainstream media.

Gupta encountered this shift in attitude during the run of his 2004 exhibition at Habitat. The curator Radhika Singh had organized complementary movie screenings, and she invited two organizations to participate, including a queer student group based at Jawaharlal Nehru University. The following year, Gupta returned to India, noting that he wanted “to become part of the changing face of Delhi. And to reconnect with a long-lost gay childhood.”

All photographs by Sunil Gupta © the artist/DACS and courtesy Hales Gallery, New York; Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto; and Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi

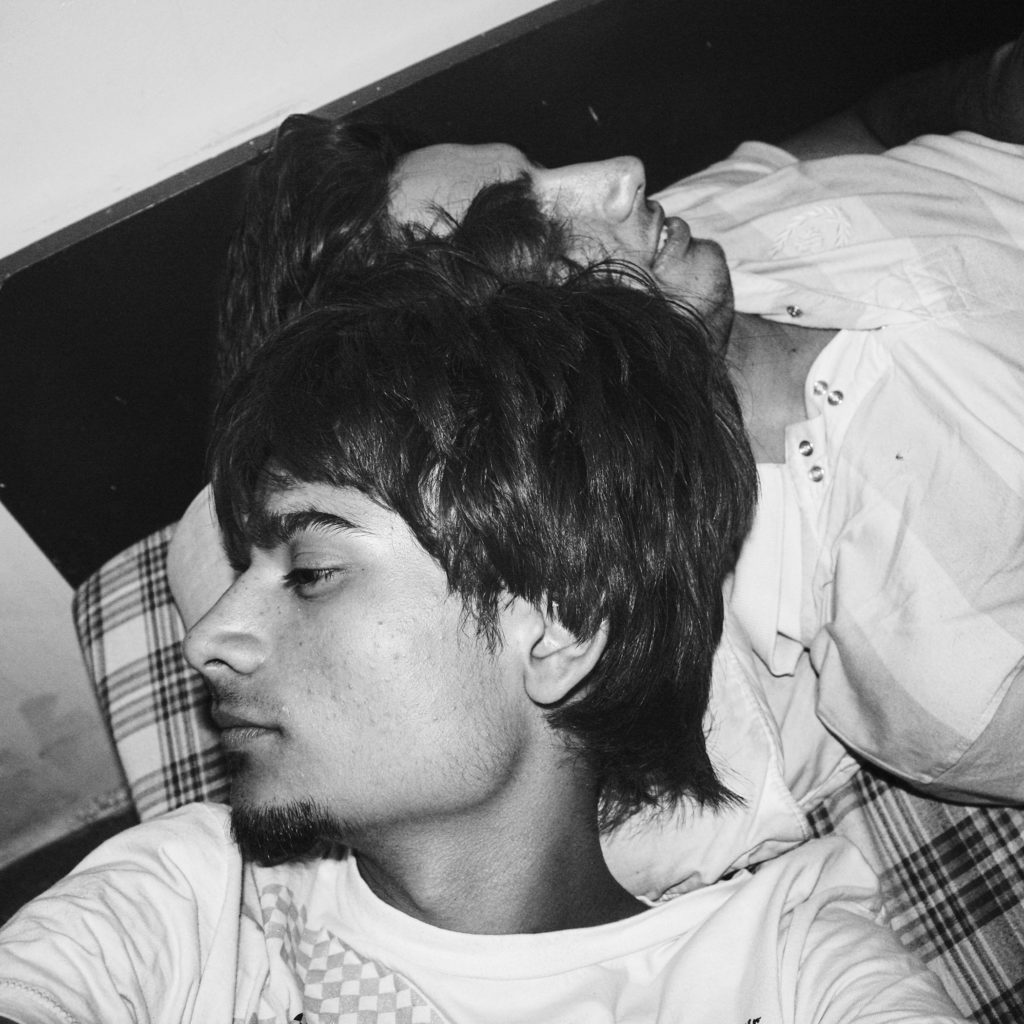

Energized, Gupta started working on a new, strikingly different series of portraits, each made on the streets of Delhi. This time, the subjects faced the camera unfazed, calm, resolute, and self-assured within the melee of the city. The people in these photographs—from an extended network of young people he began to spend time with in South Delhi—want to be seen, and, as Gupta noted, are “‘real’ people who identify their sexuality as ‘queer’ in some way.” The title Mr Malhotra’s Party (2007) is a reference to Pegs ’N’ Pints, a local nightclub that held a gay night every week, even though signs posted outdoors advertised a private party under a fictitious person’s name, a subversion of Section 377. The moniker Gupta chose for the host of his “party” was Mr. Malhotra.

Exiles and Mr Malhotra’s Party are, in fact, twinned projects. Gupta was no longer confronted with the clandestine lives of gay men. Instead, the people pictured in Mr Malhotra’s Party assert that they are not disembodied subjects, their forthright presence a testament to the urgent need to contest prejudice and intolerance. Between these two bodies of work, a transit is captured from the isolated, invisible, and private to the collectively proud, visible, and public. As the writer and activist Gautam Bhan has noted, “Cities belong to different publics, no single identity, no single way of life, no one sense of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ can dominate a metropolis. It is in such a city that sexuality could, should, must be able to take its different paths, where it can reach for dignity rather than a bare life.” Bhan wrote these words in 2017, in a dark time, when the 2009 ruling by the Delhi High Court that had struck down portions of Section 377 as unconstitutional had, in 2013, been overturned by India’s Supreme Court.

As the mood shifted, Gupta recalled, from “euphoria to gloom,” he began work on Delhi: Communities of Belonging (2016), a collaborative venture with his husband, Charan Singh, whom he met in 2009 at an HIV/AIDS-awareness community gathering in Delhi. Approached by a U.S. publisher to develop a book on queer life in India, Gupta and Singh focused their efforts on Delhi, photographing seventeen subjects in their homes and workplaces. The pictures are softer, quieter, and at times banal, and read as a sequence of nonintrusive glances. These images reveal how individuals and couples have negotiated and built worlds for themselves, which they inhabit fully without shame. Passages of text accompany the suite of photographs, and, unlike the chorus- like captions of Exiles, they are accounts of the subjects’ lives in their own words. Finally, on September 6, 2018, the Supreme Court of India ruled that the application of Section 377 was unconstitutional, calling it “irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary.”

Courtesy the artist

“Sunil has been a key advocate for photographers of color and queer photographers throughout his expansive career,” says Mark Sealy, the director of Autograph ABP, a photography space in London, who curated Gupta’s 2020 retrospective at the Photographers’ Gallery. “His work should be viewed primarily through the lens of an activist—one who understands fully what it means to live in a world full of intolerance and hatred.” A younger generation of photographers across India, whose work is confident, unflinching, and hot, has unequivocally taken up these concerns that Gupta pioneered.

Pulkit Mogha’s 100 Nudes project (2019) has amassed scores of amateur nude selfies voluntarily sent in by South Asian men. Roshini Kumar’s series Bad Company: The Secret Lives of Good Girls (2018) imagines an underground world of unbridled female pleasure, with women exploring the limits of their sexuality. Others have taken a more localized, quasi-documentarian approach: Sandeep T K, Indu Antony, and Soham Gupta have photographed the transgender communities of Kerala, Bangalore, and Kolkata, respectively. Members of the LGBTQIA community in eastern India are pictured in Soumya Sankar Bose’s elegant group of moody portraits Full Moon on a Dark Night (2014–ongoing), in which the sitters are swathed by inky black shadows, metaphorically attesting to the psychological traumas they have suffered because of persecution and marginalization.

Courtesy the artist

“Today, there is a great explosion of queer photographers and photography in a way that was not possible not so long ago. It has also become diverse in terms of gender fluidity and race,” Gupta says. The younger generation’s insistence on an inclusive politics of community, the coexistence of differing subjectivities that exist outside of conventional heteronormative narratives, follows the legacy of Gupta’s work and activism. In the series Friends and Their Friends (2010–15), Anoop Ray sensitively records the simple and immediate joy of unexpectedly falling into a community that nourishes and sustains. Ray had just moved from a small town to Delhi when he started to take these pictures. “In the metropolitan city,” Ray says, “I saw new relationships and the myriad of expression they held.”

With passion and resolve, these photographers depict their own experiences of community. They are fragile and vulnerable formations, networks of kinships and shared solidarities transgressing generations and borders. For Gupta, the momentum is belated but timely. “Whereas it has taken years for museums to notice work by me and my LGBT contemporaries, our queer graduates are appearing in major museum exhibitions,” Gupta says. “In the 1990s, I thought identity politics had had its day, culturally speaking, but clearly, it’s having a revival. Better late than never.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In,” under the title “We Were There.”