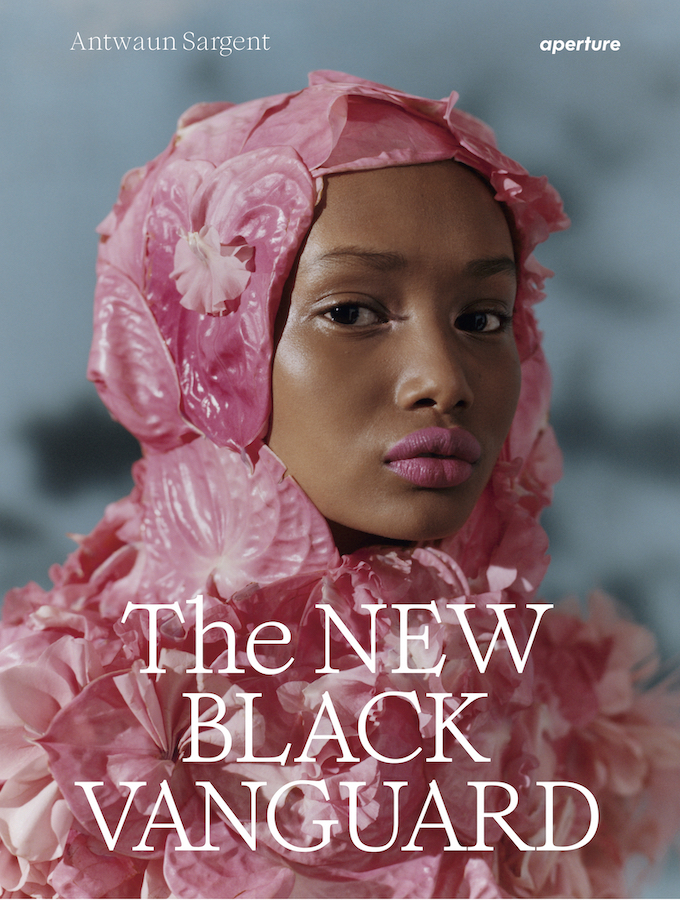

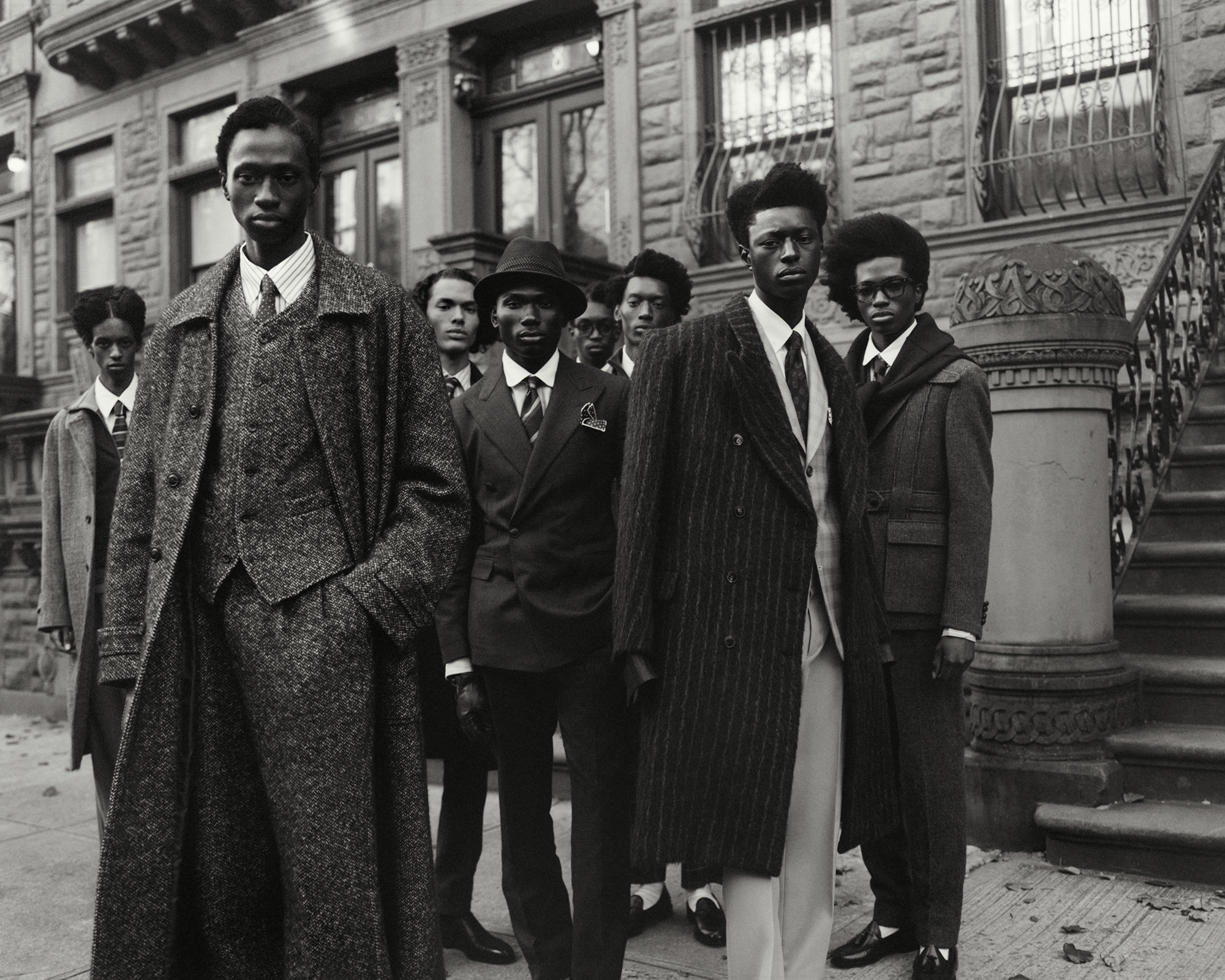

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Abdou Classic Portrait), 2024

© the artist and courtesy Gagosian

Toward the end of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), the unnamed narrator wanders into the New York City subway and witnesses three hipsters strutting through the station in zoot suits:

. . . What about those three boys, coming now along the platform, tall and slender, walking stiffly with swinging shoulders in their well-pressed, too-hot-for-summer suits, their collars high and tight about their necks, their identical hats of black cheap felt set upon the crowns of their heads with a severe formality above their hard conked hair? It was as though I’d never seen their like before: Walking slowly, their shoulders swaying, their legs swinging from their hips in trousers that ballooned upward from cuffs fitting snug about their ankles; their coats long and hip-tight with shoulders far too broad to be those of natural Western men. These fellows whose bodies seemed—what had one of my teachers said of me—“You’re like one of these African sculptures, distorted in the interest of a design.” Well, what design and whose?

The passage serves as the epigraph to Monica L. Miller’s book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity (2009), the lodestar for the exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. From the narrator’s observation comes an astute definition of flyness. A dandy is not simply someone who knows how to dress finely on special occasions; a dandy is a person who is in service to dressing well every single day, rain or shine. What is Black dandyism? A Black dandy is agitprop: an activist who subverts racial stereotypes by making their artistic or creative intelligence legible through sartorial choices. This is not easy to do. While getting dressed is quotidian, creating a narrative with clothes is a work of profound imagination. Tyler Mitchell’s photo-essay in the Superfine catalog reveals this distinction. In his portraits, details such as a slanted hat brim, a signet ring, or button placement define the wearer’s point of view and amplify their attitude.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

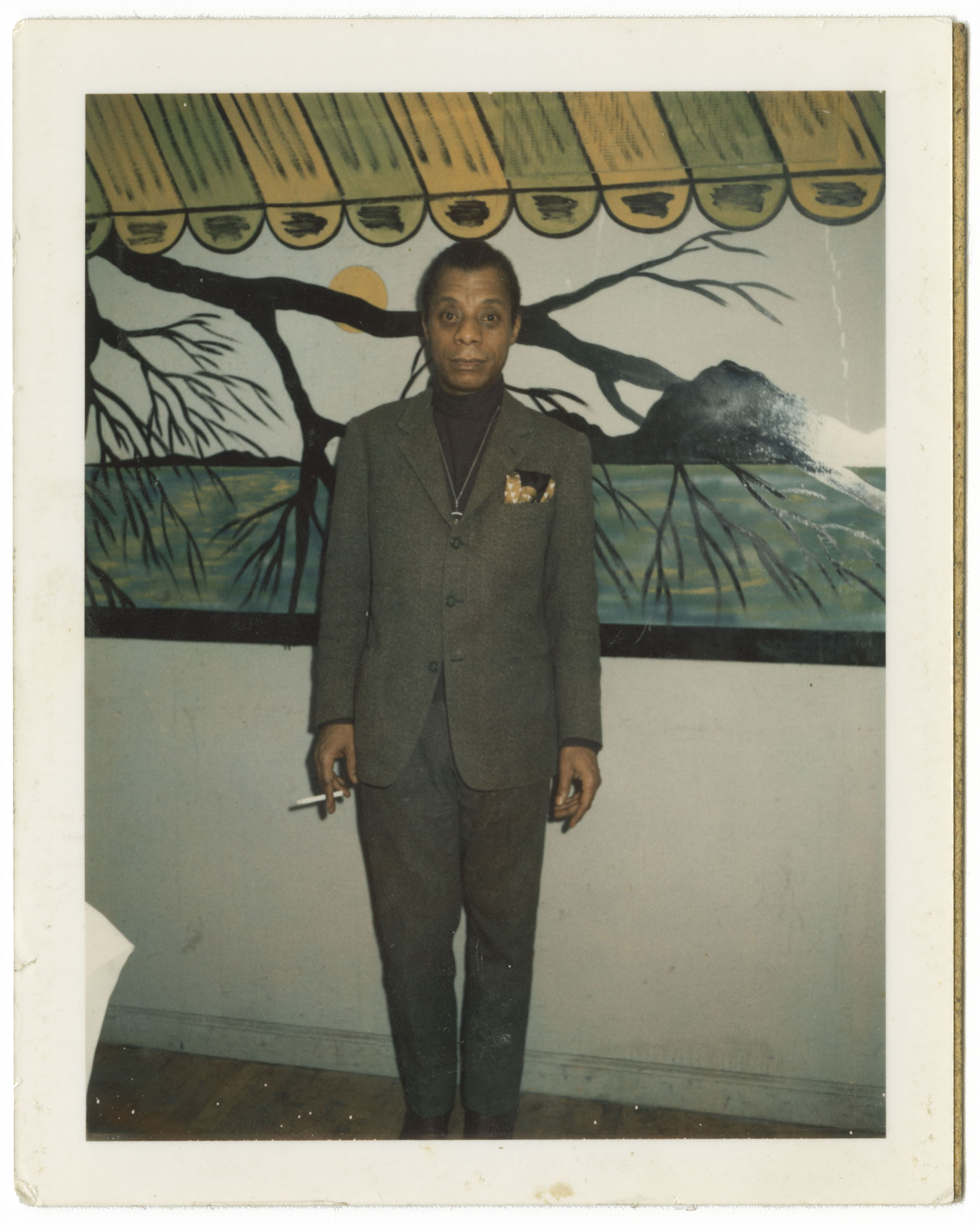

I recently met with scholars and Superfine catalog contributors Elizabeth Way, Kimberly Jenkins, and Ekow Eshun to explore what it means to be a Black dandy, how the archetype functions in Black culture, and the dandy’s place in history. We discussed iconic figures such as James Baldwin, Fredrick Douglass, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and André Leon Talley, and how their sartorial choices relate to their work and legacies. We spoke in depth about the importance of photography as a means to document the trajectory of Black dandyism globally, and about Ellison’s lifelong engagement with the medium.

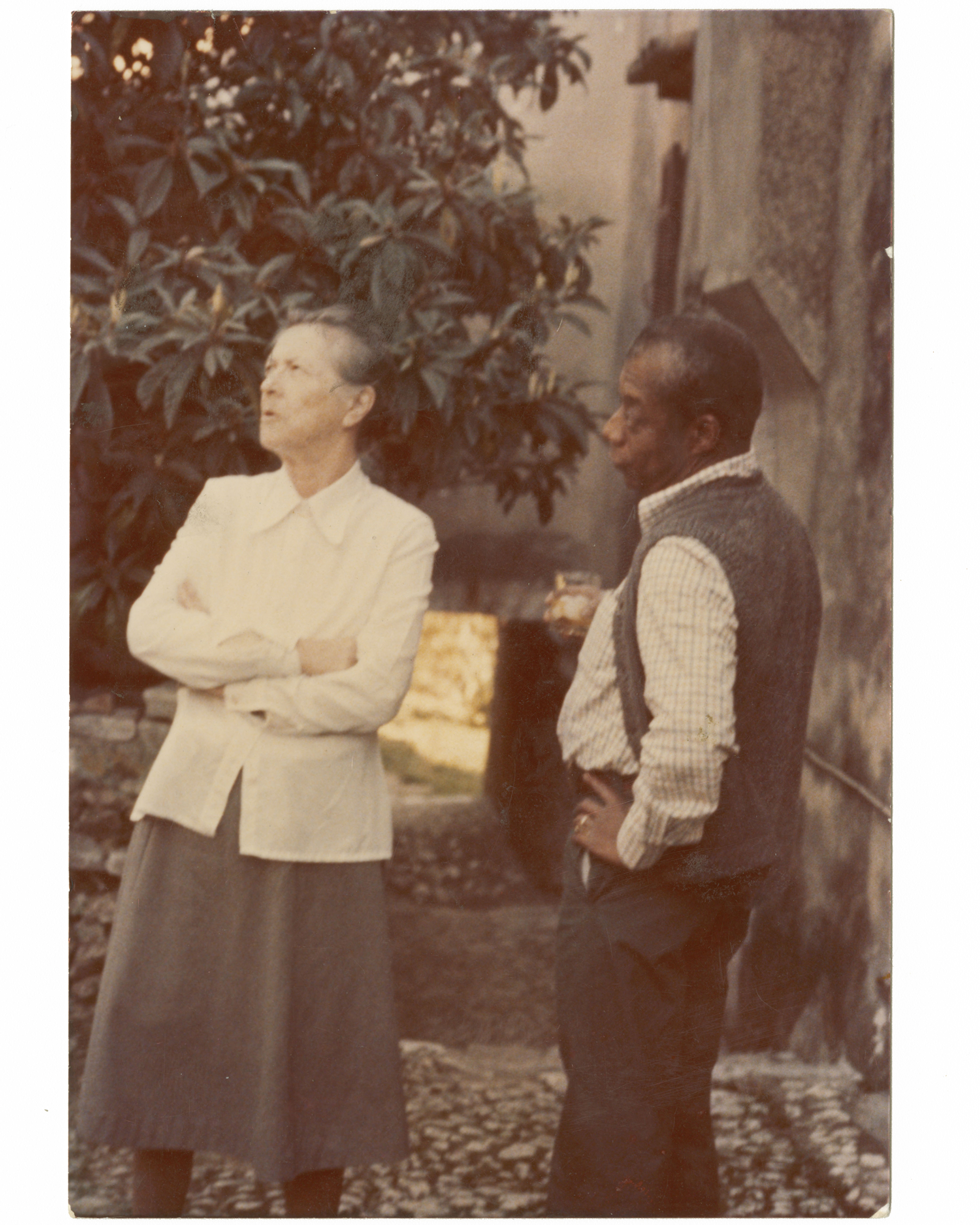

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of The Baldwin Family

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of The Baldwin Family

Monique Long: I often think about Walter Benjamin’s idea of the flaneur: a detached figure who is an observer in an urban setting at the height of the industrial age. Ekow, this idea closely aligns with your essay in the Superfine catalog and the description of James Baldwin as this solitary alienated figure. What are your thoughts of Baldwin as a dandy?

Ekow Eshun: I was interested in the James Baldwin who left America largely behind. There’s Baldwin in Switzerland, writing the essay “Stranger in the Village,” where he’s alone and feels distinctly alienated and made “other” by the experience of being the only Black person in this Swiss village in the 1950s.

But then there is Baldwin in Paris during the 1970s. He’s coming into himself in an entirely different way. He’s walking along the Left Bank. His appearance is lush and sophisticated; adorned with a scarf over his neck paired with a black top hat, and fur coat, Baldwin looks entirely at home. At the same time, he’s still writing about the experience of being Black in white environments and how difficult that continues to be. Nevertheless, when you look at him physically, something has changed. He’s more aware. He’s taken authorship of his body as well as his words.

I was interested in him as a wanderer, as a traveler, as a discoverer of self—and that journey. In a way, this is maybe the distinction between that and Benjamin’s flaneur. The flaneur walks and walks and walks. Baldwin discovers and finds himself, and I think you see that in how he conjures himself before a camera.

Long: Fascinating that you say the wanderer became a discoverer, but it’s also this notion of gumption, of taking hold of something.

Eshun: This is the distinction between the Black dandy and the Baudelairean dandy. There is more at stake. Baldwin mentions how standing out can be a matter of life and death.

Elizabeth Way: When Baldwin reaches this period in Paris, we also see a massive cultural shift in how men are dressing, the way men are presenting, the way fashion is being produced and perceived in the Left Bank.

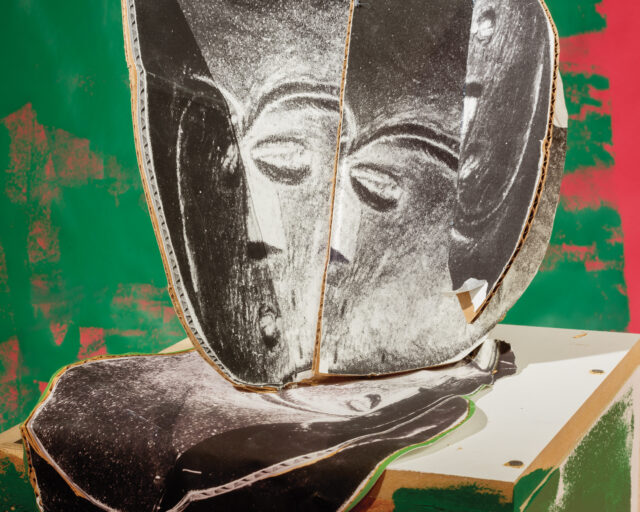

Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Z. Solomon–Janet A. Sloane Endowment Fund, 2023

Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library

Long: Barkley L. Hendricks captures that so beautifully in his paintings of that period. You can see the documentation of this radical shift in sartorial style in his photography, which eventually became the foundation of his painting.

Kimberly Jenkins: My mind instead wanders to André Leon Talley. During this same time, Talley was traveling to Europe. In 1974, he began his apprenticeship at the Costume Institute under the helm of Diana Vreeland. I can’t help but think about what he was exploring at that time and how free he felt, enjoying, in some ways, being the only Black, queer, and plus-size male figure in these spaces—though there was some tension.

Eshun: The tension you’re talking about is the freedom and constraint between being within the crowd and standing out from the crowd. André Leon Talley is an interesting example because I’m not sure if he ever experienced that freedom, as he was more interested in staying within the structure rather than going beyond it.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Long: I would love to build upon that idea of freedom for the Black dandy through the notion of constructing and deconstructing masculine and feminine characteristics. Shantrelle P. Lewis writes in Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style (Aperture, 2017) that a dandy is a queer figure. Not so much as a declaration of sexuality, but one that challenges assumptions regarding gender, affectation, flamboyance, and even high camp aesthetics.

Kimberly and Elizabeth, you both discussed this idea at length in your essays for the Superfine catalog. There’s this idea of Ellen and William Craft cross-dressing to achieve liberation. Could you talk about that? Even the duality of the phrase “Dandy Lion” that Shantrelle coins. This idea of fierceness, but also a reference to one of the most delicate flowers.

Way: In the case of Ellen and William Craft, William writes about their escape in the 1860 narrative Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom We get a sense of how they built this dandy character together—a character that consists of Ellen’s body but also William’s presence.

Ellen Craft is a woman who wants to pass as a white male slaveholder in order to escape slavery with her husband, but they must overcome all these contingencies—for example, she can’t write, so they tie up her arm in a sling. There was a fundamental idea in the nineteenth century of what it meant to be an invalid, what it meant to be ill. What it meant to be elite and ill, to be taken care of. And that state was considered feminine even for men. Ellen plays with these ideas of queerness and gender and how it introduces itself into the concept of masculinity for men at this time, later addressed within an American context known as the “elite man.”

Superfine elevates Blackness in the public consciousness, allowing people to understand its importance, impact, and beauty, recognizing it as art.

Jenkins: In my essay, I examine Sylvester James Jr., an American singer-songwriter, primarily active in the genres of disco, rhythm and blues, and soul. Sylvester was known for his flamboyant and androgynous appearance, but wasn’t interested in the use of labels for gender fluidity. In terms of his fashion, it was about standing out, borrowing different looks from vintage or thrift stores, and playing with gender in various ways.

For example, I mentioned a jacket by Pat Campano, a sequined jacket similar to those of the early 1980s commonly seen on Phyllis Hyman or even later on Luther Vandross. It’s a fusion of the masculine and feminine elements that create this tension, while simultaneously fostering a sense of freedom through style, fashion, and dress.

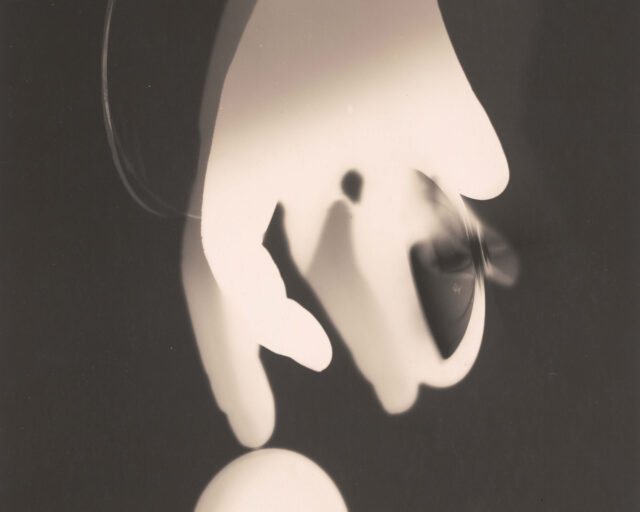

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Long: Elizabeth, you recently organized an exhibition, Africa’s Fashion Diaspora, at the Museum at FIT, featuring several generations of fashion designers of African descent from the 1950s to the present. Are there aesthetic characteristics or distinctions that define a dandy based on where they’re from?

Way: What I found so exciting about Africa’s Fashion Diaspora and these designers is that they leaned into their cultural identity in terms of fashioning themselves. You can see the cultural background, the ethos, and the geography of these dandies in a room. But what they all have in common is discipline—this idea of freshness, crispness, and cleanliness.

Jenkins: Color and materiality definitely come into play from a geographical perspective. When you look at the Sapeurs in Congo, or various parts of Africa, there’s this attraction to bright colors. Often, these dandies are incredibly conspicuous with logos and designer labels. Not only are vibrant colors more appreciated, but there’s more to communicate in terms of portraying what you can afford, which can show your sense of self-worth or assist with social mobility.

Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Eshun: We can see distinctions between the visual aesthetics of dandyism in various places, but what I’m more interested in stressing, as you say, Kimberly, is the inherently hybrid syncretic, cosmopolitan nature of the dandy. The dandy takes from everywhere to make their own. The idea of the dandy is also a project against authenticity. Against the idea that there is a singular way to dress rather than a form of self-fashioning that is constantly in process, in a way, both in tune with and against the currents of the everyday.

Way: That’s an important concept to think about when women use suiting, use menswear to craft their sartorial personas, because it’s not about passing as men; it’s about destabilizing the idea of masculinity and femininity.

Eshun: In the 1990s, I interviewed Prince at Paisley Park in London. It was fascinating. Similar to the earlier mention of Sylvester, Prince played with these notions of appropriateness and the ways a Black person might comport themselves. Prince’s presence went beyond the stage. His high heels and costumes invoke a sense of freedom, a way of walking through the world unapologetically. In a way, the dandy offers space for others who may be less free to occupy, explore, and assert space on their own terms.

Long: Superfine is a multimedia exhibition, but photography is something we always return to when thinking about the Black dandy. The ethos of this presentation of someone who’s negotiating racial stereotypes and wearing this kind of armor, this style that’s beyond reproach.

Can we discuss this relationship between photography and the Black dandy? Ekow, you had your show Made You Look: Dandyism and Black Masculinity, at the Photographer’s Gallery, in London, several years ago. Do you want to talk about the impetus for the show and why you decided to focus on photography?

Eshun: The camera has been responsible for typologizing and stereotyping Black figures. The dandy alters this narrative by staging a strategic intervention in front of the camera, using the lens to reassert visibility and presence on their own terms. I continue to be interested in the simultaneous way that photographers behind the lens and dandies in front of the lens collaborate as a means to disrupt an overarching white gaze, to suggest other ways of comportment. This is partially about dress, but it’s also about status and how you command presence.

Jenkins: That’s beautifully said. I completely agree. That need to mediate the image that you’re presenting based on the past. It is a great deal of pressure and part of the injustice of our inability to just be ourselves.

I think of the nineteenth-century figure of a Zip Coon: the gaudy-dressing dandy who doesn’t know his place, as seen in Edward Williams Clay’s Life in Philadelphia, depicting mocking cartoons of a fashionable Black man who’s always getting it wrong—he’s so gaudy, he’s so colorful, he doesn’t understand the codes of tasteful dress. Finding that place between defying those stereotypes and being authentic while pushing boundaries is quite a balancing act.

Way: Photography, as opposed to other forms of capturing images, is an interesting place for Black dandyism to exist. There is agency in the photographer, but Tina Campt also talks about this agency in the sitter. Campt looks specifically at prison photos, explaining that there is still a way to listen to that image and to see that subject pushing back. The camera is not neutral. There is power up for grabs, but the sitter can snatch a little bit of that even when the odds are stacked against them.

However, I also think a great deal about the concept of the counter-archive and its importance for Black people to create images for a sympathetic audience. Photography on the Color Line (Duke University Press, 2004), by Shawn Michelle Smith, examines the counter-archive. It’s not just about minstrel shows and cartoons that specifically think about fashion. It’s postcards of Black bodies being lynched. It’s the Southern views of this romantic idea of Black poverty, not to mention the scientific racism that the camera has been applied to.

It’s this avalanche of images every time a Black person sits in front of the camera to express themselves. Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois were producing images for vast and largely white audiences, but there were also many amazing family albums, images that were made to sit on mantles, which beautifully define the counter-archive.

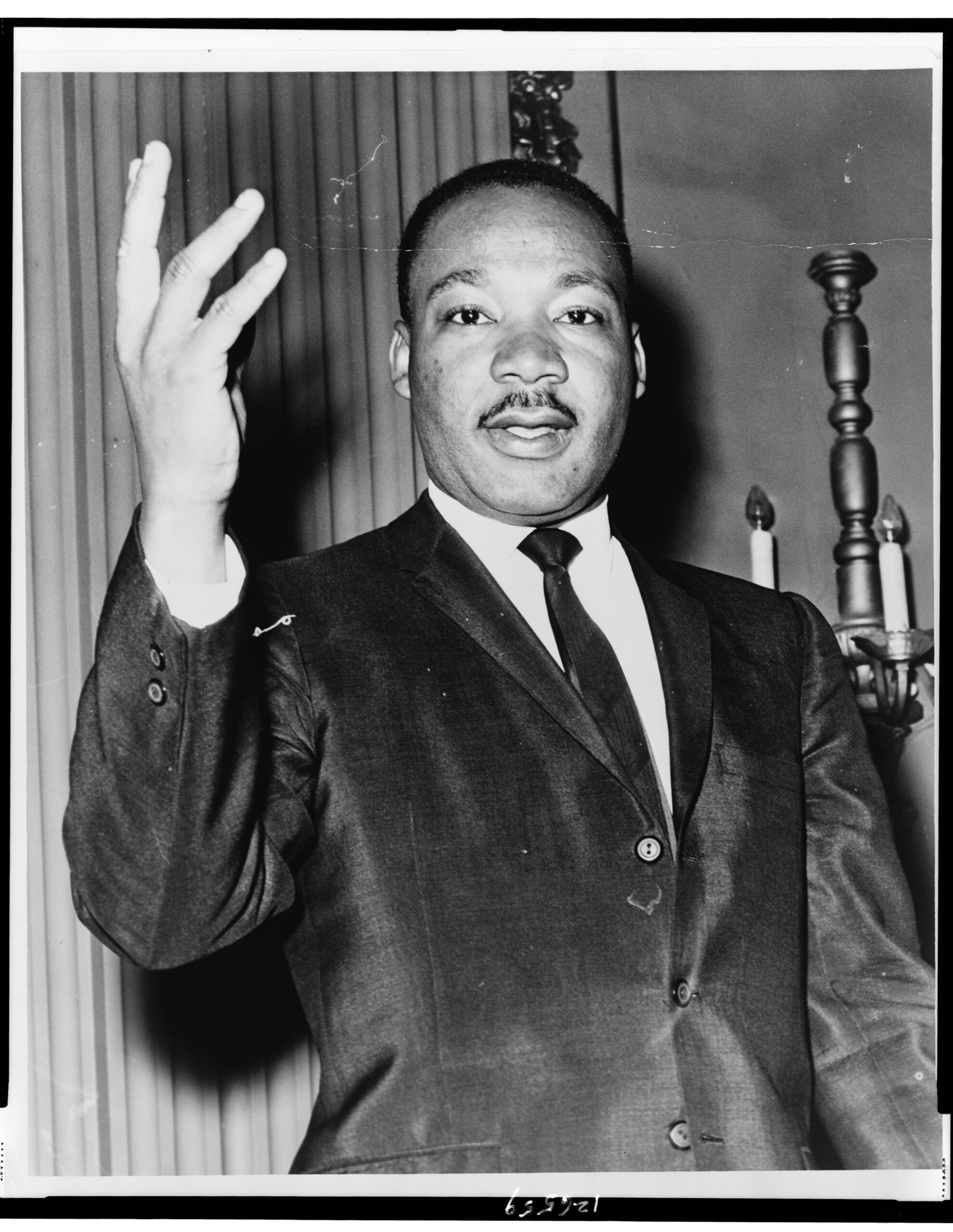

Courtesy the Library of Congress

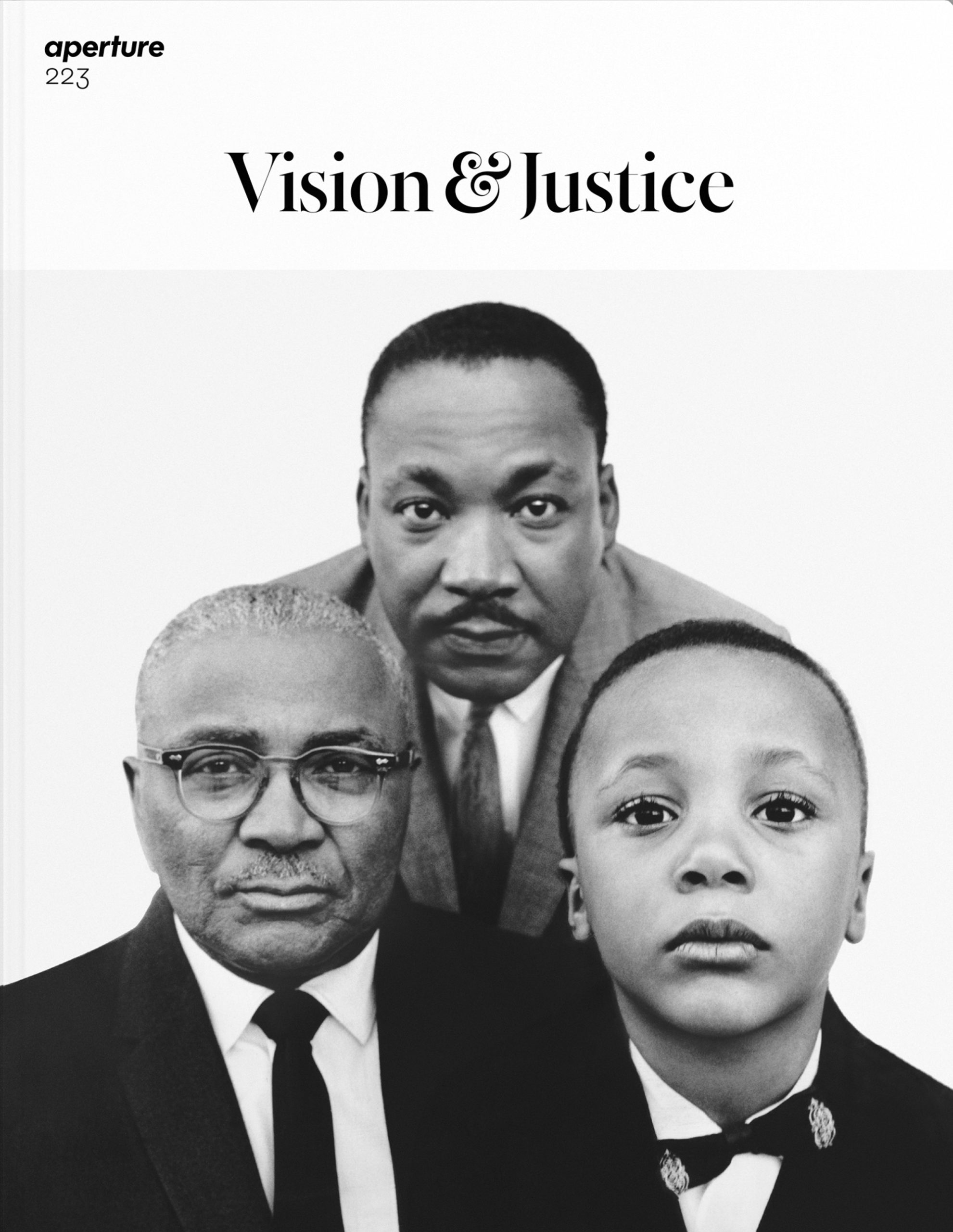

Long: I like to think that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was aware of Frederick Douglass’s strategy as well. I know King doesn’t often get included in the discussion around dandies, but I would argue he was one. Kimberly, I spotted your issue of Vision and Justice [Aperture No. 223, 2016] behind you, which is what prompted my thought of Dr. King in his signature uniform of the traditional suit. Yet, the media was steadfast in projecting a particular image of Dr. King. Even when they marched in the hot sun, you can almost read on his face that he wants to hold on to that agency, the agency of the sitter powerfully linking arms with men who are dressed exactly like him.

In a way, you see the ethos of street photography. An idea of this intersection between fashion and what people wear on the street as body armor and self-expression. Dr. King also had to contend with the emerging medium of television.

Jenkins: Also, the images of him being arrested sabotaged all the respectability that they were trying to convey.

Way: It was the footage of people so carefully dressed and being treated so violently, so appallingly. It was those images being broadcasted across national and international television that were so powerful.

Eshun: Perhaps we should address the idea of “dandy” as a verb. To dandy. To dandy, which might mean to assert, to make visible, to disrupt, to disquiet, to defy taste, to reach beyond all these things. The consequences and implications of dress as a form of politics, as a form of display, as a form of standing out in consciousness of the risk that that might evolve.

© the artist and courtesy Gagosian

Long: The importance of Black image making is such a powerful sentiment, one that is clearly stated throughout the show and exhibition catalog, particularly through Tyler Mitchell’s body of work as a young photographer. We’re able to gain an understanding of how his lens adds nuance to the Black male gaze, image making, and the self-fashioning of Black bodies today. He’s at this intersection of editorial—which constructs fantasy, creates desire, longing—and visual art.

Eshun: Tyler’s fantastically gifted at bringing into reality what might otherwise remain in dreaming. He understands the nature of what it takes to craft an image, to present a sense of longing, desire, memory, and hope for purity. He also educates himself on the work of other photographers, such as Gordon Parks. I think he’s found a compelling visual language that has elegance and sophistication, yet at its heart, a desire for a world where the Black figure is recognized in its fullness and splendor.

Way: He was a critical artist in the catalog in relation to the exhibition. The American public views the Costume Institute exhibition largely through the lens of the gala, as well as the reputation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art as an elite space. Tyler not only captures the beauty of Black men, but he also helps the viewer understand why this subject matter belongs in the Costume Institute and at the Met. This is only the second menswear exhibition the Costume Institute has ever done in its history.

Superfine: Tailoring Black Style elevates Blackness in the public consciousness, allowing people to understand its importance, impact, and beauty, recognizing it as art. These images help take us there, not only for Blackness but also for male fashion history, which is often not deemed as interesting, beautiful, or worthy of exhibition.

Superfine: Tailoring Black Style is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, through October 26.