Whatever Happened to Corporate Extravagance?

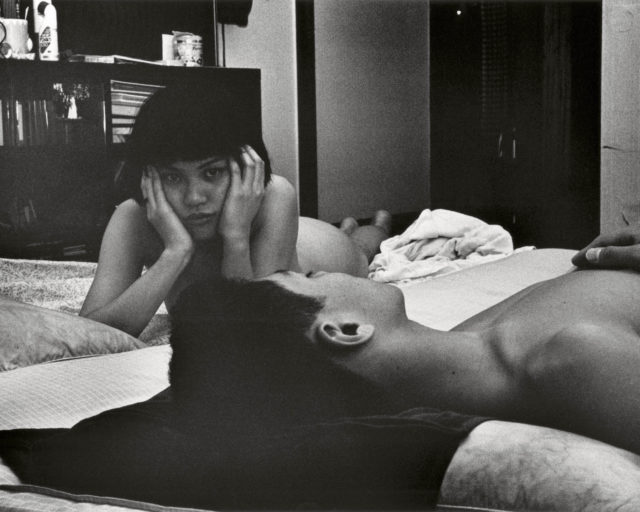

Susan Ressler, System Development Corporation, 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

Coworking spaces, open-plan postindustrial lofts, lounge areas, telecommuting—today’s flexible desk culture has wiped nearly every semblance of the traditional corner office into oblivion. Companies favor the open-source, the perma-lance, the OOO, but always online. So, only forty years after they were taken, Susan Ressler’s photographs of corporate headquarters seem more an anthropological study than a blueprint for a contemporary workplace. The guarded quarters of powerful transactions display a controlling exactitude.

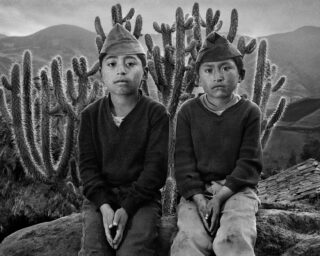

Susan Ressler, Atlantic Richfield, 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

A recent exhibition at Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego—based on Ressler’s book of the same name, Executive Order: Images of 1970s Corporate America—considered corporate interiors that flaunt gleaming veneers and plush corners waiting behind sets of spotless glass double doors. The photograph Atlantic Richfield (1980), for example—part of the Los Angeles Documentary Project, a National Endowment initiative for documenting the city—radiates wealth and broadcasts financial success, all bold geometric details and extravagant materials. ARCO, as Atlantic Richfield oil company had come to be known, tightly controlled its public-facing quarters, all smoothed-down fabrics and quiet hallways. Ressler documented its lobby space, decorated with of-the-moment details of high design. The wall-to-wall carpet is freshly vacuumed, and all footsteps have been erased. A fortress of dark leather club chairs surrounds a coffee table polished to an impeccable shine; a minimal wall work, a blank pie chart, hangs on the wall behind them. An Alexander Calder mobile dangles above, its kinetic dance the only element emitting evidence of any oxygen in the room.

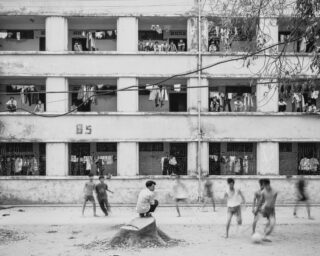

Susan Ressler, Filmways, 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

The pared-down rigidity in Filmways submits to a notion of inclusivity and openness, but only on the company’s terms: the dark panels enclosing the conference room appear to be lacking in natural light, and the neat row of chairs are an indirect invitation to sit at the table. The seating in The Capital Group, Inc nods to a less-formal setup, but reinforces the closed nature of the circle of participants, while photographs like Systems Development Corporation, Wednesday, and Honeywell (all 1980) project precise images of industry sophistication.

Susan Ressler, The Capital Group, Inc., 1980, from the series Los Angeles Documentary Project

Courtesy the artist and Joseph Bellows Gallery, San Diego

The Dallas ARCO Tower, forty-nine stories of imposing smoked glass anchoring ARCO Plaza downtown, opened in 1983. In 1977, ARCO had merged with the copper mining Anaconda Company, a major investment in copper mines in the American West. By the mid-1980s, only a handful of years after Ressler made Atlantic Richfield, it become clear that ARCO’s finesse in extracting oil failed to translate into the same success in copper extraction. The Anaconda land was partitioned and sold off, and in 1985, ARCO was acquired by a Dutch trader, who soon passed it off to Sunoco. Scraping by as the no-frills gas station, ARCO was sold to and absorbed into BP Amoco by 2000. In 2008, it was decreed that the once-powerful oil company owed $187 million to the Environmental Protection Agency for restoration of the towns of Butte and Anaconda, the company’s territories in Montana that included the Berkeley Pit, once the “richest hill on Earth.” Perhaps presaging the company’s own oversteps, it is now classified as a Superfund site.

Executive Order: Images of 1970s Corporate America was published by Daylight Books in April 2018.