From Teju Cole, an Exhibition as "Tone Poem"

Whitten Sabbatini, Couple Embracing, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Teju Cole’s first major curatorial project, Go Down Moses, is a triumphant presentation of the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s permanent collection. Founded in 1976 by Columbia College Chicago, the MoCP began collecting in 1979 and now has over 15,000 objects. For Go Down Moses, Cole, a writer and photography critic, selected a range of photographs from this vast collection, creating what he calls a “visual tone poem.” Divided between three floors, the show is a visual feast of compositionally striking work and unlikely, yet captivating pairings.

In the first room, Cole intersperses images of landscapes (presumably American ones) with those of body parts. While the juxtaposition is compelling—instigating visual associations between the human form and land—each work is powerful enough in its own right. Cole includes Dorothea Lange’s Toquerville, 1953, Belle Bringhurst and neighbor children, which depicts the back of a gray-haired woman’s head, her tight, twisted bun drawing the eye. In a photograph by Esther Parada, the back and base of the neck of a black person in a simple cloth shirt become a landscape of textual detail. These pieces are compositionally brilliant, yet utterly quotidian.

Christian Patterson, 24th Street Road (Road at Night), 2007

Courtesy the artist

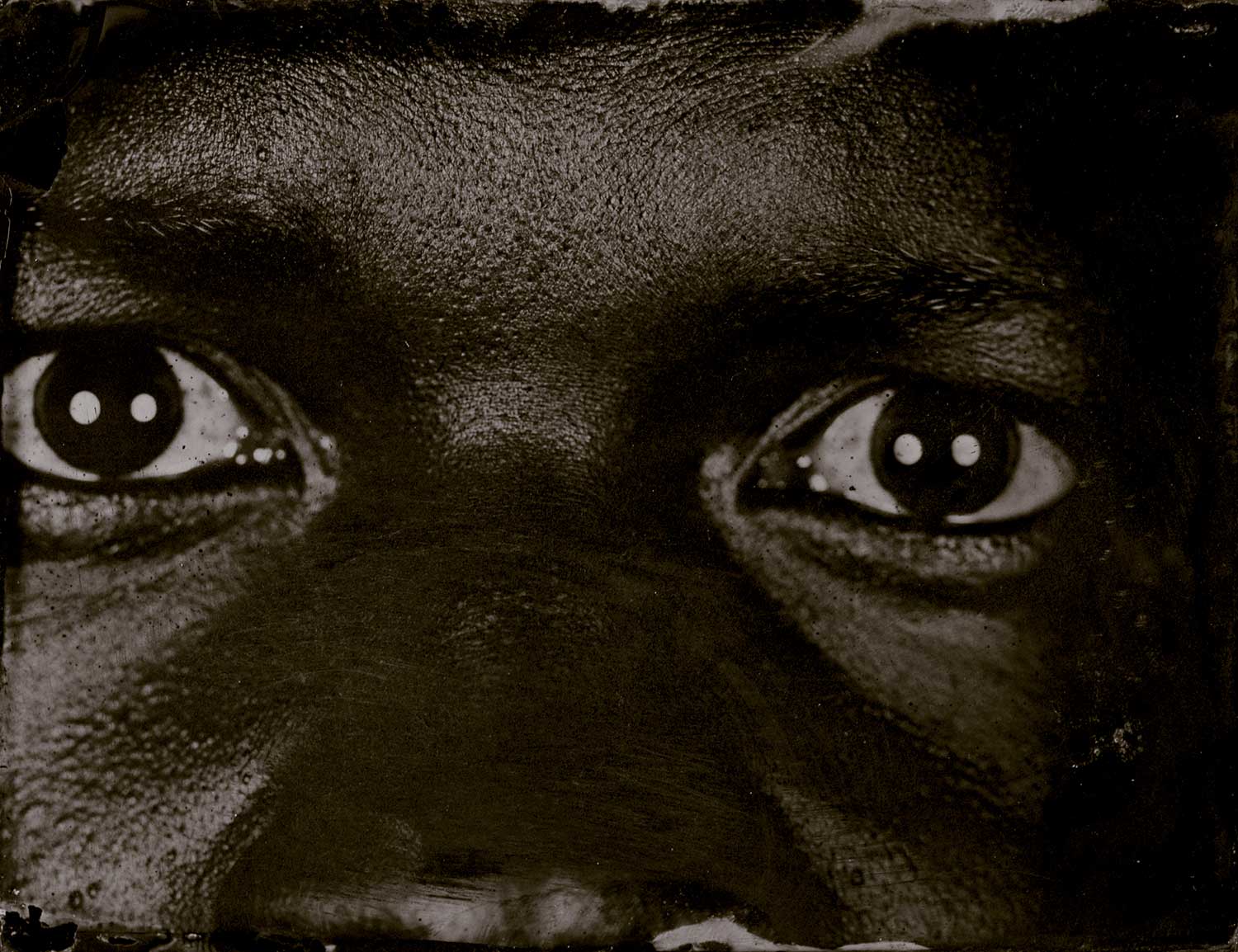

Cole has long thought about photographic representations of black people, as evidenced in his earlier musings on the delicate touch of photographers like Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks, who harnessed the camera’s technology to capture black subjects. Cole’s selections for Go Down Moses illuminate his continued interest in presenting the beauty of black skin. Stephen Feldman’s 1966 Portrait, for example, situates a black man against an entirely black background, where the only visible light is reflected off the sweat on his face; in the resulting profile, only a mouth, nose, and eye are clearly discernible. There are also several works from Myra Greene’s arresting 2007 series Character Recognition; glass ambrotypes present sectioned parts of her body and consider the black body’s role in identity formation.

Myra Greene, Untitled #38, from the series Character Recognition, 2007

Courtesy the artist

The last room of the exhibition features two walls. On the first, longer wall, photographs hang floor-to-ceiling salon-style and range from iconic to lesser-known images, and from banal, everyday visuals to those of violence and destruction. Danny Lyon’s historic 1964 image of the National Guard assaulting photographer Clifford Vaughs is more or less centered in this grouping: a moment of uniquely American violence at the center of Cole’s mini-history of photography. The photograph’s modest size, however, renders it just one small part of a larger whole, especially in relation to its much larger neighbors by artists like An-My Lê, Anthony Haughey, and Alec Soth. The all-too-common nature of violence in the US is on display in Lyon’s striking image, as well as in Cole’s other selections, featuring overturned cars, burning buildings, and even planes in the process of destruction. Alongside these, Cole includes photographs of environmental degradation, American military force, and American consumerism.

On the final, jet-black wall of the gallery, under low light, is Roy DeCarava’s Man in Window (1978). The image is almost too dark to be seen at first glance; under low light, the print’s presentation is radically different from the rest of the exhibition. DeCarava is known for his stunning play of light and darkness and his ability to sidestep the technical camera limitations that typically favor pale skin—and Cole has previously expressed a deep admiration for DeCarava’s use of shadow to reveal the texture, depth, and beauty of black skin. Man in Window is a quiet conclusion. It is an image that encapsulates many of the themes of Go Down Moses, while simultaneously existing outside of the narrative. Cole fittingly considers the image to be his “grace note.”

Melissa Ann Pinney, Selan’s Beauty School, 1988

Courtesy the artist

Go Down Moses asks a timely question: is hope still possible, given the chaos of our present moment? Cole’s words and his curation remind us that moments of change, of upheaval, are not new: this archive tells us that the state of disruption—the chaos in our environmental, political, social, and cultural worlds—has happened before. He also reminds us that photographers have sought hope through their medium since its invention. At the conclusion of his curatorial statement, Cole proposes a new definition of hope, one in which hope is hospitality exchanged in solidarity between the weary. The images in Go Down Moses show us how brilliant and terrifying the world can be—how immense beauty exists with immense pain and destruction. In the end, what Cole offers us through his careful selection of photographs is this hospitality—this hope.

Go Down Moses is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia College Chicago through September 29, 2019.