“The word dandy may evoke ideas of bygone white men in waistcoats and multilayered blouses with puffy sleeves,” writes Shantrelle P. Lewis, in her book, Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style. Historically, dandyism has been outside the traditional tropes of masculinity—queer, in a sense—dandies also threatened the existing class structure by dressing up. A Black man employing this strategy is even more radical and subversive. By looking sharp, the Black dandy fashions a sense of pride, positivity, and self-worth that can transcend circumstances, as well as societal perceptions. He defies monolithic understandings of what it is to be a man—particularly a Black man—through a colorful and complex dance between race, class, gender, power, and style. Today, the fashion of Black dandies is more a nod to the style of their well-dressed grandfathers than the likes of Oscar Wilde or Beau Brummell. With styles as diverse as their subjects’, each of the following photographers portrays a striking relationship to dandyism.

Courtesy the artist

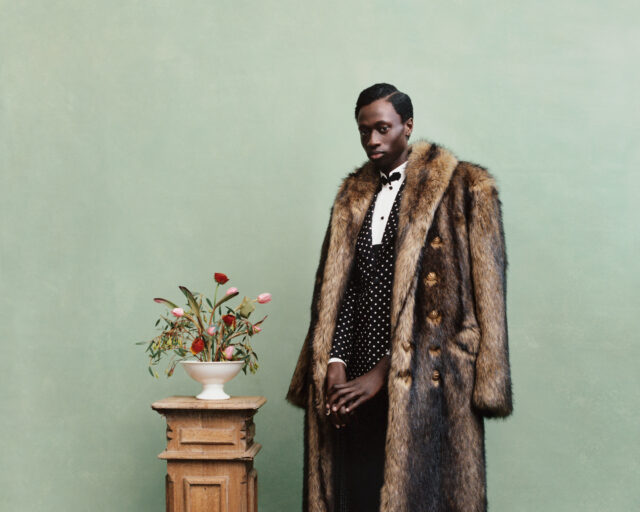

Sara Shamsavari

Sara Shamsavari has long photographed London’s Rude Boys as a way of shattering stereotypes of immigrants. Born in Tehran, Shamsavari is a British artist concerned with cultural identity and social justice. A bit of history—in England, eighteenth-century enslaved Africans were often dressed lavishly to reflect well on their owners, and they soon began personalizing those uniforms. Fast-forward to the 1960s, when waves of Black immigrants flocked to the UK from Anglophone countries in the Caribbean and West Africa, bringing their colorful and vibrant styles with them. The Rude boys were arbiters of style as soon as they arrived from Kingston, Jamaica. Modern-day Rude Boys come from all over and continue to influence global fashion.

Courtesy the artist

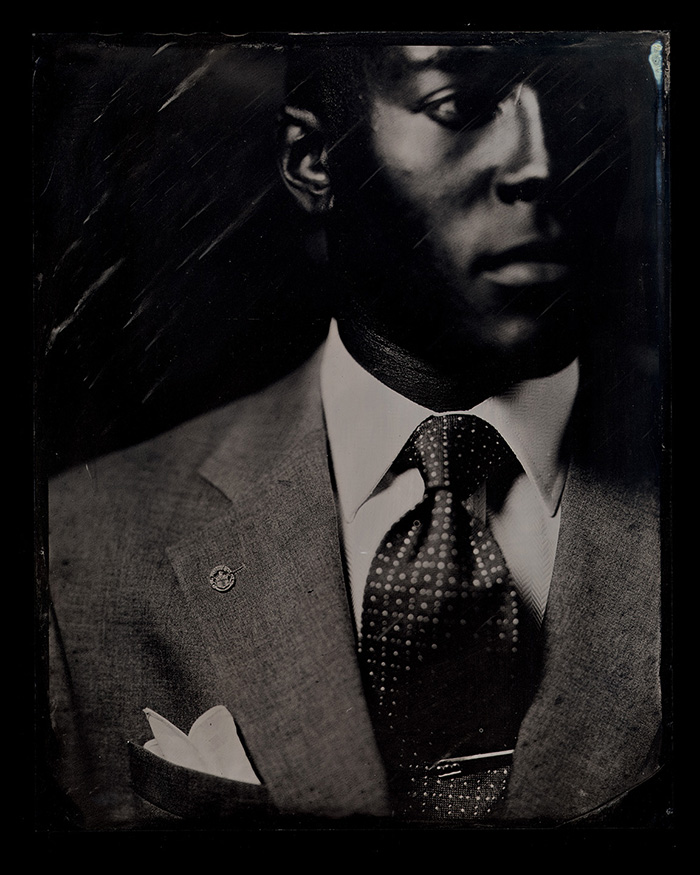

Jody Ake

Jody Ake, born and raised in the South but now living in Portland, Oregon, creates rare and delicate ambrotypes. Developed in the 1850s as a less-expensive alternative to the daguerreotype, the ambrotype is a labor-intensive process that requires creating, exposing, and processing an image on a glass plate over about fifteen minutes. Ake’s historic-looking portraits of twenty-first-century Black men convey self-actualization and identity. On first glance, it may even be easier to believe that the images were created in a past century than in the last decade.

Courtesy of the artist and Marie Finaz Gallery

Daniele Tamagni

Daniele Tamagni photographs one of the oldest sartorial movements, the Sapeurs. It dates back to the late nineteenth century, when Europeans first colonized the Congo, and locals imitated their mannerisms and dress. Over the past hundred years, this cult of extravagant clothing and elegance became known as La Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (The Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People) or La Sape. Tamagni’s series Gentlemen of Bacongo (2009) has influenced style-based social movements around the world.

Courtesy the artist

Rose Callahan

Rose Callahan has been well immersed in the world of dandyism since starting her blog The Dandy Portraits in early 2008. She explains the essential elements of dandyism: “Dressing is elevated to an art, and they have cultivated exceptional, refined personal style based in classic menswear, with a healthy dose of eccentricity and obsession. Dressing is a huge part, but it is never the whole picture. There is undoubtedly a strength of personality and a desire to cultivate a life according to one’s own rules.”

Courtesy the artist

Andrew Dosunmu

Photographer and filmmaker Andrew Dosunmu was born in Nigeria, moved to London as a teen, and currently lives in Brooklyn. He is deeply influenced by cinema, particularly the Senegalese filmmakers Ousmane Sembène and Djibril Diop Mambéty. His films present intimate and moving portraits of African immigrants’ stories. But, as Dosunmu explains, most projects begin with pictures: “Photos are my scrapbook. It gives me the freedom to make cinema on paper.”

Courtesy the artist

Harness Hamese

Self-taught photographer Harness Hamese belongs to Khumbula, a Johannesburg collective of vintage enthusiasts. Named after a Nguni word meaning “to remember,” the collective is inspired by the philosophy, aesthetics, and actions of anti-apartheid freedom fighters, such as Nelson Mandela and Steve Biko. Hamese explains, “We focus particularly on how our parents used to dress, and the integrity that’s attached to these expressions of individualism and independence.” His images communicate both the African past of the vintage clothes and the present of the wearers, breaking down stereotypes of what Africa was and is.

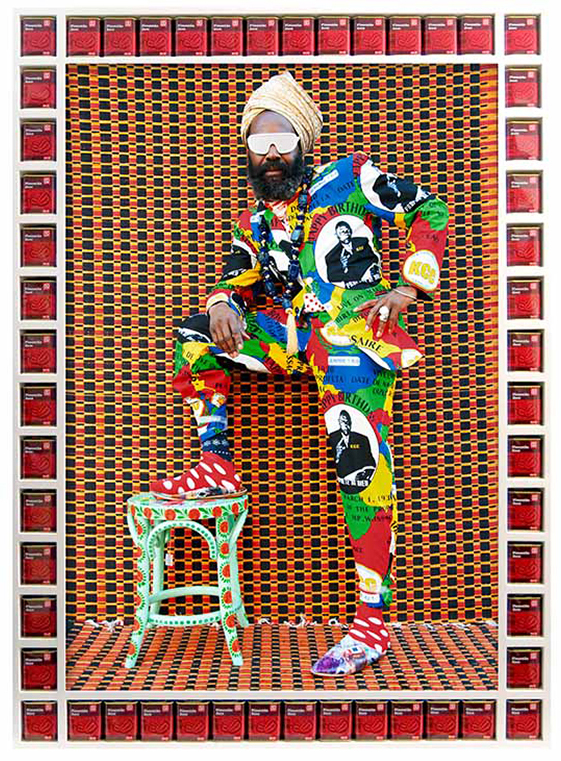

© the artist and courtesy Taymour Grahne Gallery, New York

Hassan Hajjaj

Extraordinary and out-of-the-box, Hassan Hajjaj’s studio portraits show a clash of cultures, art forms, and expressions of creativity. A photographer, artist, and stylist, Hajjaj collaborates with his subjects as well as a tailor to conceptualize flamboyant ensembles through traditional clothes and suits. Hajjaj’s series is a conversation about how cultures collide and fuse—he is as influenced by Andy Warhol as he is by Malick Sidibé—and speaks to a childhood with memories of an African past and a European present. His Moroccan “rock stars” are as flashy as the commercial products that he uses to frame them.

© the artist and Arteh Creative

Arteh Odjidja

Arteh Odjidja’s Stranger in Moscow series tells the story of a young, African immigrant in Russia. Odjidja met Habdulay Vilhette, a young man from a small island off the coast of West Africa, at a local casting call for a fashion shoot. Odjidja became interested in what it was like for a Black man living in Russia. He fashioned him as “the stranger” in this visual essay, shot in an exquisite Ozwald Boateng suit, in which Vilhette’s dark complexion and six foot three inch height made for a striking juxtaposition against a mainly white Moscow.

Courtesy the artist

Rog and Bee Walker

Rog and Bee Walker have the makings of a timeless love story. They are celebrated as photographers, muses, style mavens, and sartorialists. On their first date, they went to see the documentary Bill Cunningham New York (2010) and, a year later, Rog proposed. Rog is best-known for his collaboration with the creative agency Street Etiquette, while Bee’s practice ranges from social documentary to lifestyle photography.

© the artist and courtesy of Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris

Omar Victor Diop

Senegalese photographer and artist Omar Victor Diop situates his subjects in settings reminiscent of those of his Francophone West African predecessors Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, who produced studio portraits of young, progressive West Africans in the 1960s and ’70s. His bold use of color, however, adds a contemporary twist. In one image, a set of twins, or a subject and his replica—one traditional, one Western—sit perfectly poised, their heads covered, in blue batik jackets.

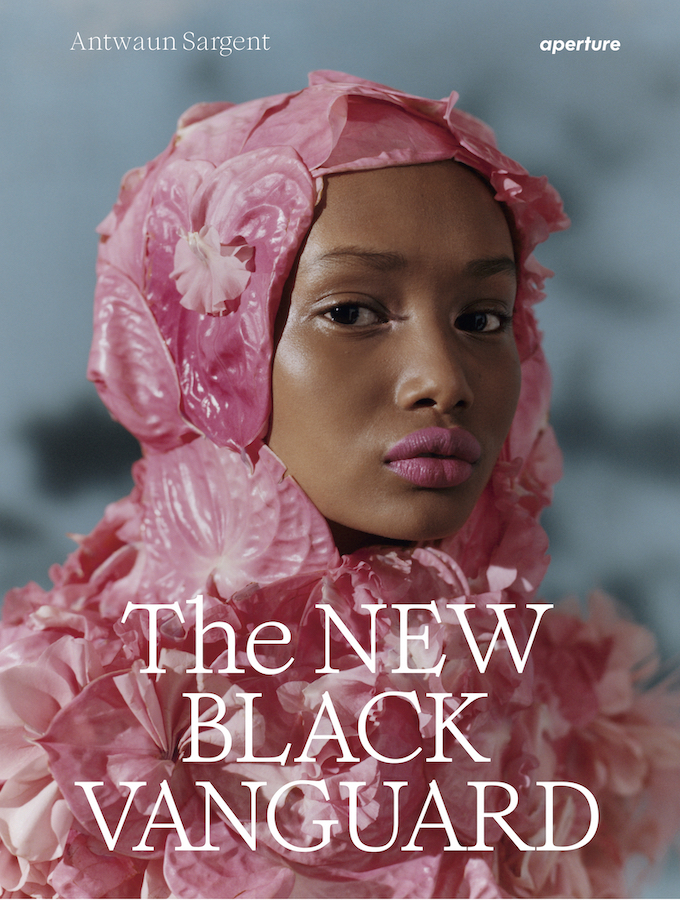

Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style (2017) is published by Aperture.