Widline Cadet, You Won’t Be Here Forever, 2020, for Aperture

Widline Cadet has been sitting in the light for three seasons. Before the pandemic, she always had something else to do (working away at her MFA at Syracuse University, where she graduated this past spring; and fielding commissions for publications such as California Sunday Magazine), or she had somewhere else to be (residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine or Lighthouse Works on Fishers Island in New York). The demands of social distancing, however, brought an abrupt, ecstatic stillness to her routine; suddenly, she had time to follow the movements of the sun.

“Our living room had this magical light, where I would wake up at seven in the morning, every morning, to just watch the light,” Cadet says of the home in Syracuse she’s recently moved away from. “I spent most of the early spring and summer going to the backyard and watching the sunset, too, for a while.” This fall, stationed in New York City as an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Cadet still tracks the light. In a new body of work, You Won’t Be Here Forever, a burnt-orange glow undulates across photographs taken both Upstate and in the city, flickering in and out of her camera’s gaze.

“I try to erase time as much as I can,” Cadet says of these enigmatic images of unnamed outdoor spaces, strangers, and friends. “I try to be ambiguous about where these pictures were taken, or when, or what’s happening.” Cadet refuses explicit reference to the painful frenzies of 2020. Nonetheless, the aesthetics of social distancing permeate the work: she made most of these photographs on her solitary walks through her former and current cities of residence.

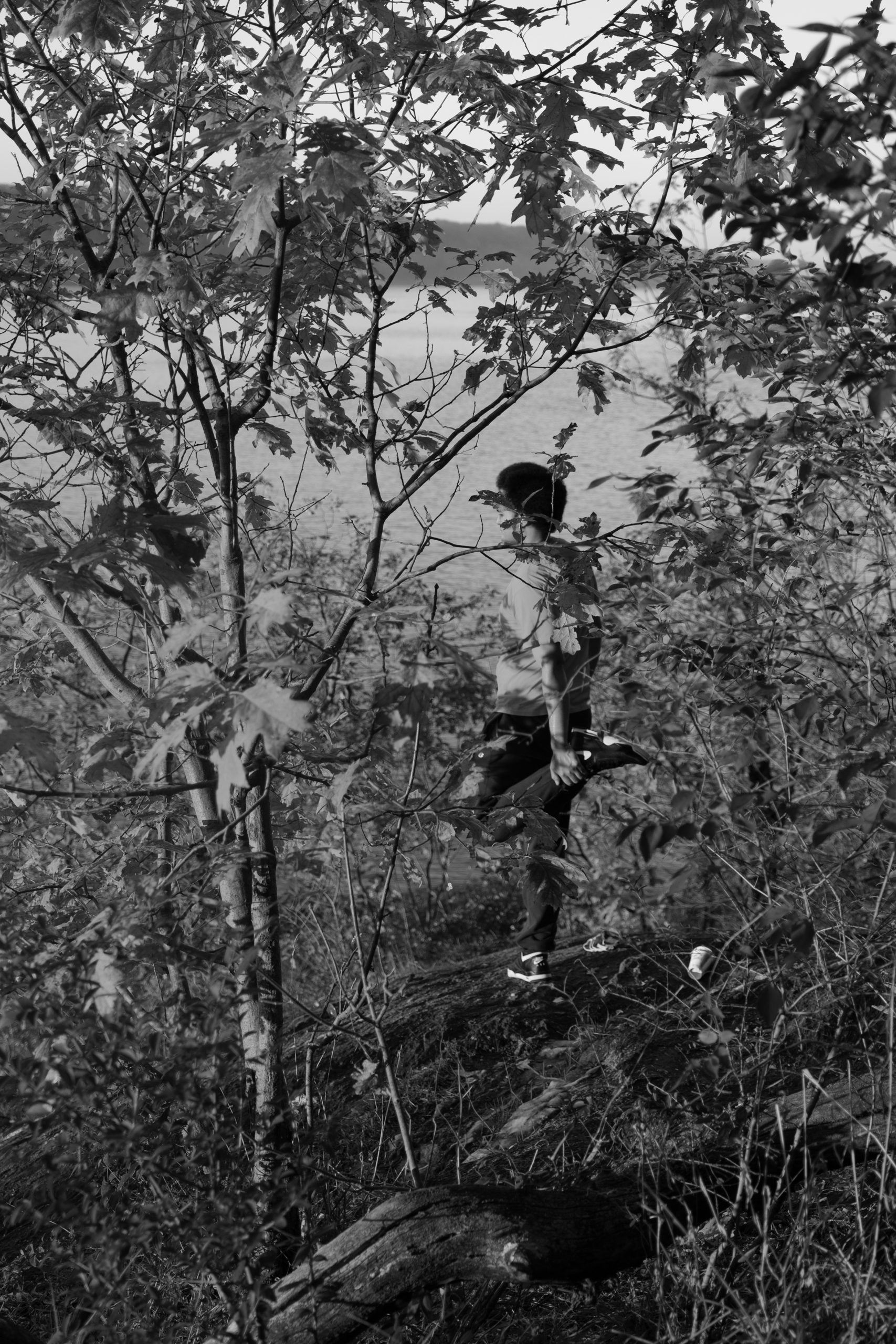

In these images, human subjects are conspicuously distant from the camera. Shoulders slant away, backs are firmly turned, or nature intervenes to shroud them. In one, a profusion of tree branches nearly claims a man as its own, so that his stance—balanced on one leg, the other leg pulled back into a stretch—becomes a kind of sprouting. Even in a rare instance of physical proximity, a portrait of a person in a satin slip and Western hat, the subject looks away from the camera in favor of the trees. Their brown skin and brown hat are beautifully congruent with the lush green of the firs, both where they are sun-dappled and where they are in shadow.

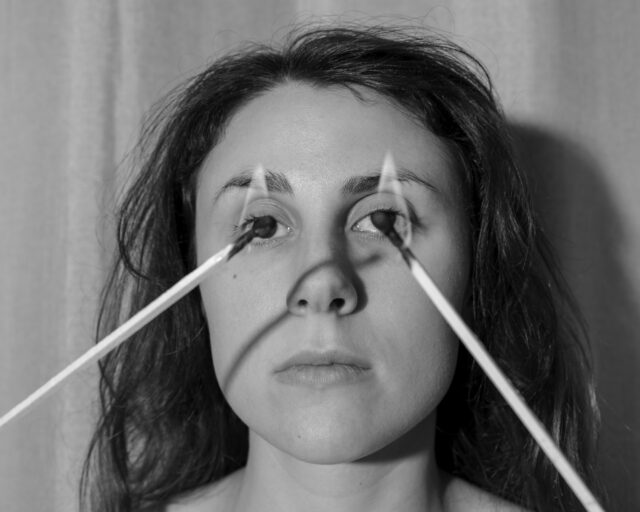

In the absence of interpersonal touch, Cadet’s photographs cultivate a type of alternative intimacy. Disparate textures meet and kiss. A fuzzy, silhouetted head greets crisp, looming bridge beams. A stocky bush caresses the stone wall and wire window grate of a building’s side. Cadet considers these contact points inherently optimistic—signs of natural life and familiar landscapes still converging, even through another season of unnatural isolation. “There’s this serious hopefulness that I have that I try to put into pictures in some way,” she says, and indeed, her gaze on these daily joys feels serious, carefully measured—the inflections of warm, bright light all the more invigorating for the solemnity and solitude that spurred their documentation.

Still, her optimism emanates unbridled. In one photograph, a pair of hands cradles berries from a tree, the palms cupped so patiently they could be outstretched in benediction. This moment joins a constellation of images Cadet has made of Black people in communion with nature. In an ongoing body of work she started in 2017, Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]appearances), “most of the photographs,” Cadet says, “are of Black women and greenery and these abstract landscapes.” In her series Soft (2017) and Home Bodies (2013–ongoing), as well, the surrounding flora often frames her subjects. Cadet calls this mediation of greenery “a way of hiding myself and hiding the figures,” but her hiding practice is less like masking, more like tucking her subjects into a landscape where they can be carefully held. Those subjects are a mixture of Cadet’s loved ones, total strangers, and herself, and Cadet’s avoidance in telling the viewer the difference serves as another way of hiding, holding back her relationship to the figures, so that they may all be ambiguously loved.

In You Won’t Be Here Forever, some amendments needed to be made. “I include my siblings randomly in every body of work that I do. Except for this one,” says Cadet. (She hasn’t been able to see much of her family during the pandemic.) And unlike in Seremoni Disparisyon, Cadet does not explicitly appear alongside her other subjects here. She’s found a new way to hide. In a photograph of her old living room in Syracuse, taken just before she moved out and during one of her seven AM sessions in the morning sunlight, a print of a 2018 portrait, San Tit (Untitled), leans against a wall, turned upside down. It’s partially, perhaps intentionally, obscured by a separate wooden frame and other objects, left last to be packed away before Cadet left the apartment that was her home for three years and her solace for three lonesome months in quarantine.

There’s a painstaking quality to the way San Tit (Untitled) is tucked away, and cut from view is the other young Black woman in the original portrait, on whose stomach the artist gently rests her head. But she is still there. Cadet would like to erase time in her photographs; this one keeps her held in perpetual light, embraced, without distance, by another.

Courtesy the artist