The Photographs That Help Us Celebrate When Nothing Feels Ordinary

How images of holidays and ceremonies become a form of honoring, grieving, or marking time.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Hartford, 1978

© the artist and courtesy David Zwirner Gallery, New York

A pack of wolves gathers to celebrate the birth of a pup. They look up at the sky, eagerness in their eyes, and howl in unison. All of them welcome births with joy, and must have from their beginning, I think; and wonder what the first humans celebrated. Newly standing up, likely some covering on their naked, hairy bodies—did they celebrate their difference from other animals? Probably not. At the birth of a tiny, bloody one emerging from another’s body, did they howl like wolves? To celebrate is a behavior that the human species took time to develop, though cave drawings might be a version of celebration.

From long-ago, unpictured days, humans have found ways for communally expressing grief and showing joy. Affection, attachment, love, fellowship, feelings toward others must have been transmitted with grimaces, hugs, shrugs, headshakes, gestures for all occasions. Then, events must have sprung up: a huge bonfire at harvest time, a totem pole to honor gods, sun worship at dawn, a merging of clans in something like marriage. Feelings for and about oneself and others—pride, shame, rage, jealousy—ancient texts attest to them.

Courtesy the artist

There are the spontaneous or the planned or the obligatory celebrations, analogous to Claude Lévi-Strauss’s idea of “the raw and the cooked,” the dialectics of culture, “categorical opposites drawn from everyday experience.” Of the cooked: U.S. civil society has Thanksgiving, an ignorant and disturbing holiday, mostly enjoyed or suffered for overeating, decidedly not enjoyed by First Americans whose ancestors were massacred by white Europeans. Halloween, nonobligatory and semi-raw, is fun, most especially for children, when disguise offers them a chance to be superheroes and scare adults, while adults can regress to childhood. About which the comic Richard Lewis quipped: “At Halloween, my family dresses up as obstacles.”

Few people celebrate failure, but the British commemorate a failed revolution with Guy Fawkes Day. On the street, children ask, “Penny for the guy?” A resilient irony rescues the British from maudlin sentimentality, except at Christmas.

Celebrations proclaim significant moments and events, and also shape the appropriate responses. They teach people when to applaud or weep.

Weddings, Christmas, birthdays, the planning for these occasions sows happiness, worry, and agitation; then come their festive, or not, results. Ask a friend: “Did you get gifts for Christmas when you were a child?” or, “Did you have birthday parties?” The response will be immediate and specific, details often vivid and surprising, or so vague and bland as to indicate trauma. Holidays can be the most ambivalent days of your life.

“I’m going home for Christmas” might begin a stand-up comic’s routine, while many movies depend on family fractiousness for plot points. Getting home may be difficult, flights bumped, but being at home can be bumpier. Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s 1978 scene of an overdecorated living room in Hartford is Christmas gone wild. Without people, it’s an expectant, perfectly idealized Christmas. The reality of adults arguing near the tree imposes itself on the picture, while a lament can be heard: Why did we ever come home?

© Getty Images

Sociologists claim celebrations foster social cohesion by honoring key community figures, denoting public accomplishments and private ones, such as success in love with marriage ceremonies and medals awarded for daring and courage in war. Celebrations proclaim significant moments and events, and also shape the appropriate responses—a gold watch for retirement after fifty years. They teach people when to applaud or weep, and sometimes people do both at weddings and funerals.

President Barack Obama’s 2008 election night was tense, exciting, dramatic. A Black man had been nominated for president in a nation whose written Constitution recognized slavery, embedding racism within it. Black communities were buoyed by possibility, and enthusiasm for Obama crossed races. Many non-Black Americans didn’t feel it, not at all. And his win most likely aroused their already active and latent racism.

Courtesy the artist

In Chicago, where Obama lived and was a U.S. senator, Michal Czerwonka documented the ecstasy at his 2008 victory gathering in Grant Park. Two American flags and Obama’s image on a placard wave behind a crowd of beaming supporters; in the foreground, an exultant young Black man has raised his fist in the Black Power salute. The gesture also foregrounds the civil rights movement, without which a Barack Obama wouldn’t have had a chance in hell. He had run on hope, and hope animates Czerwonka’s photograph. Now, it is an image of unfulfilled wishes.

Covid lockdown, masking, and being housebound, everyone felt like a prisoner. In the summer of 2020, about two months into the pandemic, whatever fears these Brooklyn neighbors felt, they ran into the streets, masks on, to escape their boredom, for a block party known as St. James Joy. “There was dancing in the street,” to quote Martha and the Vandellas. Pictures of the event burst with human energy and the beauty of spontaneity, exemplifying what well planned events can’t ever do—let the moment happen, when sudden pleasure roars, when nothing else matters, it’s just full on partying.

© the artist and courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Now, with vaccinations, apartment doors have opened. People meet and greet. There’s still need for caution—the threat of new variants—but there’s reason enough to celebrate the advent of almost ordinary life. The first season of Succession launched with an episode titled “Celebration.” The eightieth-birthday luncheon for the patriarch, Logan Roy (le roi), was attended by his entire nuclear, or unclear, family. No one enjoyed it, especially the birthday boy. The ironic festivity united the series’ disunited characters, inviting Succession’s viewers into the family’s vicious infighting. Some birthdays are like that.

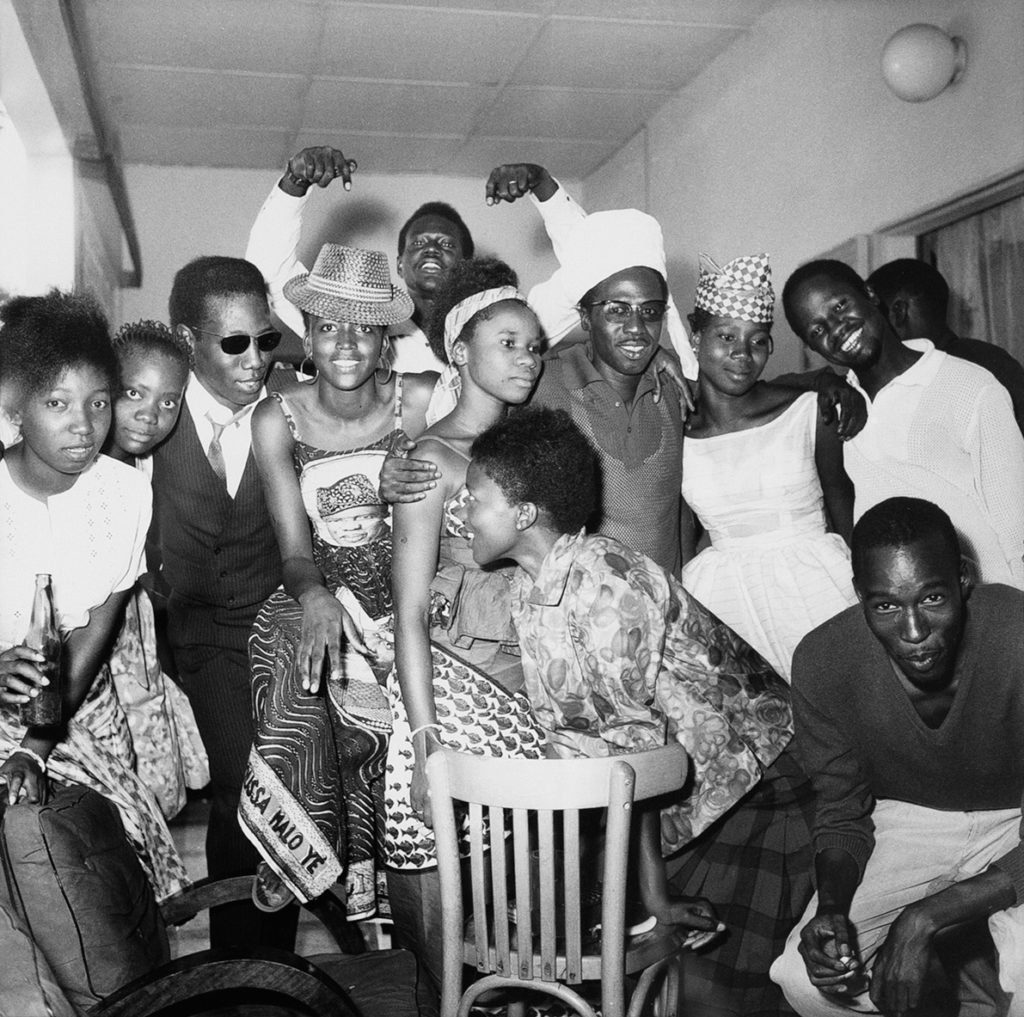

Malick Sidibé’s photograph of a jolly family gathering in Soirée familiale (1966) sings with ebullience. The family’s liveliness overflows the frame. Most of the group looks at his camera, but not everyone. Those not looking, otherwise engaged, register individuals as related to each other and unique from each other. Sidibé didn’t insist, Look at me, the camera, smile, the standard gimmicks to organize group portraits. He let this family act as it wanted. Maybe they’re being themselves, though one can’t know. The family composition thrives with personality, a portrait of resemblances and differences.

In Frances F. Denny’s Cake, Cambridge, MA (2013), a round, high, heavily frosted white cake is metonymic, either for a birthday or small wedding. Cake might even be a tiny monument to the uniformity of celebrations. Sitting on a black table that disappears under it, Denny’s cake is spotlighted like a movie star. But half of it is gone, likely eaten, so the cake is undone. The assumption is that it was once whole, which comments on the ways viewers narrate pictures, imagining a before them and an after them. The exposed interior might be, curiously, about interiority, what lies beneath or inside a luscious surface. Nobody’s waiting for a slice, and Denny’s solitary half cake says, It’s over. On reflection, the party might not have been as sweet as the cake, now just a leftover.

© 2021 The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

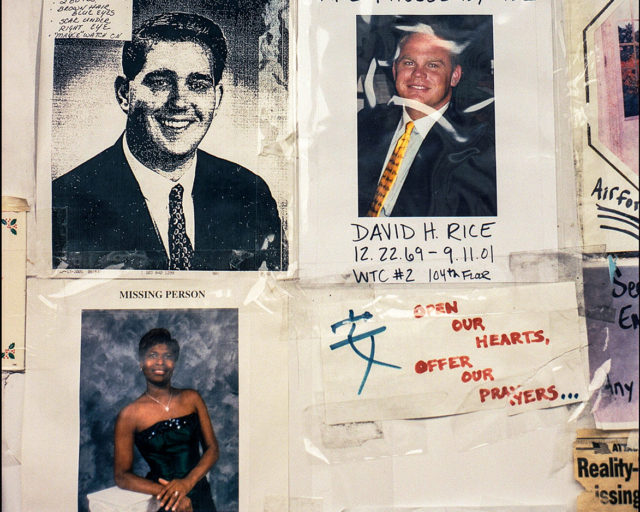

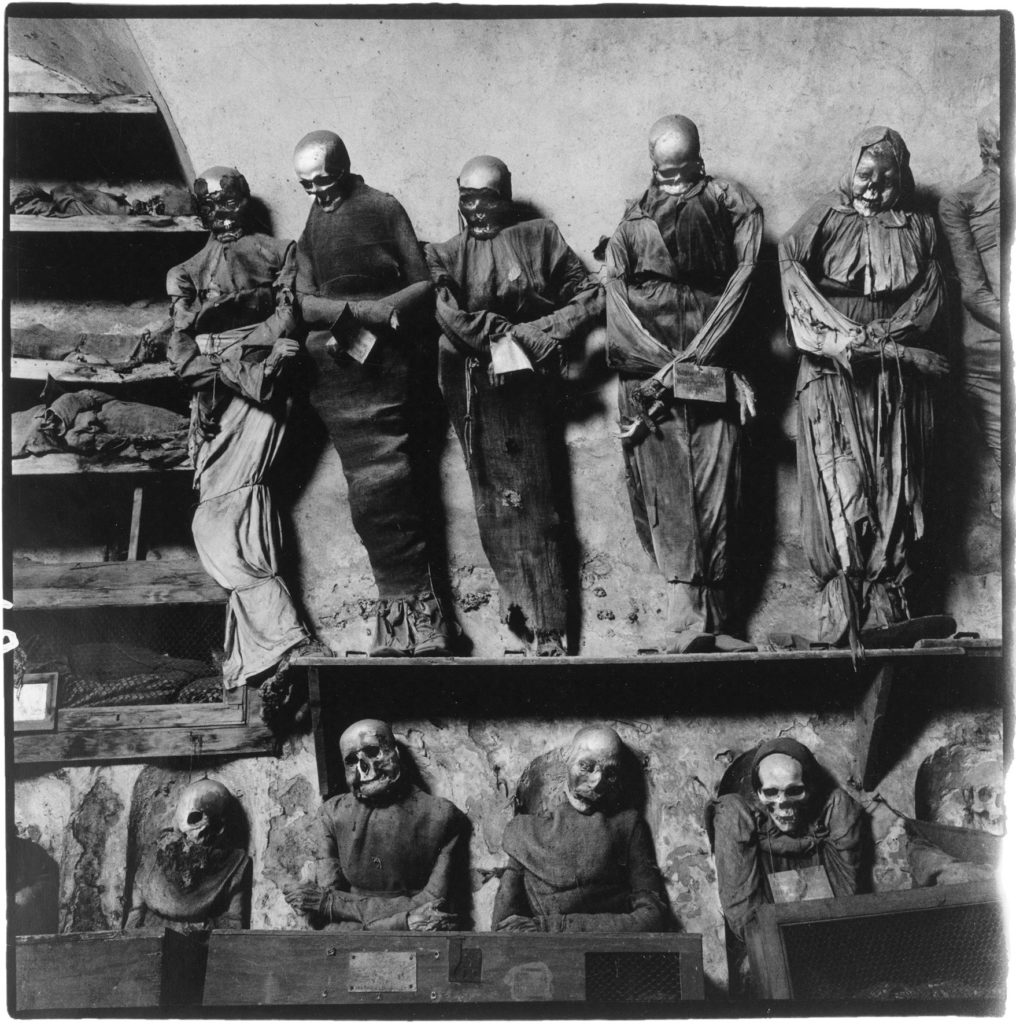

Photography’s genesis must have been influenced by people’s fascination with themselves; knowing death awaits is a perpetual insult to their narcissism. Might a picture subvert eternal disappearance? “Life is a movie. Death is a photograph,” Susan Sontag famously wrote. She saw a still object, necessarily of the past, the subject absent—death. But a photograph is seen by the living who enliven it with meaning. It is, instead, a fitting subjectfor a photograph, this stasis.

The dead are also celebrated, honored, and photographers’ concepts range as widely as burial customs. Peter Hujar’s elegant style in Palermo Catacombs #11 (1963) articulates the texture and architecture of the tombs. In the sixteenth century, the Capuchin friars used these crypts when their cemetery became full. Initially, they dried the corpses, dousing them with vinegar to preserve them.

Hujar’s photograph is shocking, the way death is. Hujar wants to see death, get close, focus on details. God is in the details, and maybe death is also. Their robes drape around their mummified bodies. Those faces, their icy expressions, what do they tell us? Standing up, the dead might just walk away. The liminal passage between life and death—she passed, he passed—is heightened by Hujar’s inclusion of a staircase, signifying ascension and descent. The friars will walk up and down it, until, one day, they can’t.

Courtesy the artist

Far from Palermo, the death of a drummer, James Black, merits a traditional New Orleans jazz funeral in 1988. It’s a joyous celebration. Chandra McCormick places the stark white, flower bedecked casket, raised high by pallbearers, in the center, motoring the dynamic procession and the photograph. Some of the Black and non-Black mourners have raised their fists. So many people surround it, fan out from it, walking in front of and behind it, the coffin might be floating in the air, even though three pronounced arms do the work. James Black’s life of making music has ended, and the tunes he played and loved will see him out. Exultant faces proclaim their fervent belief: James is going to a better place.

In the here and now, celebrating feels right. The vaccine—and the promise of helpful new pills—is freeing people to roam the streets, meet in bars, go shopping, see friends, dine out—even the usual seems a celebration. Nothing feels ordinary, though, while it is also very ordinary, except for the threat of the vexing unvaxxed and new variants. Still, it’s a dangerous world where much more than viruses are killing people. Many would still prefer to stay home.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the title “What Makes a Celebration?”