The Radiant Intimacy of Jarod Lew’s Family Portraits

At home in suburban Detroit, the Chinese American photographer invokes the unstable fantasias of personal memory.

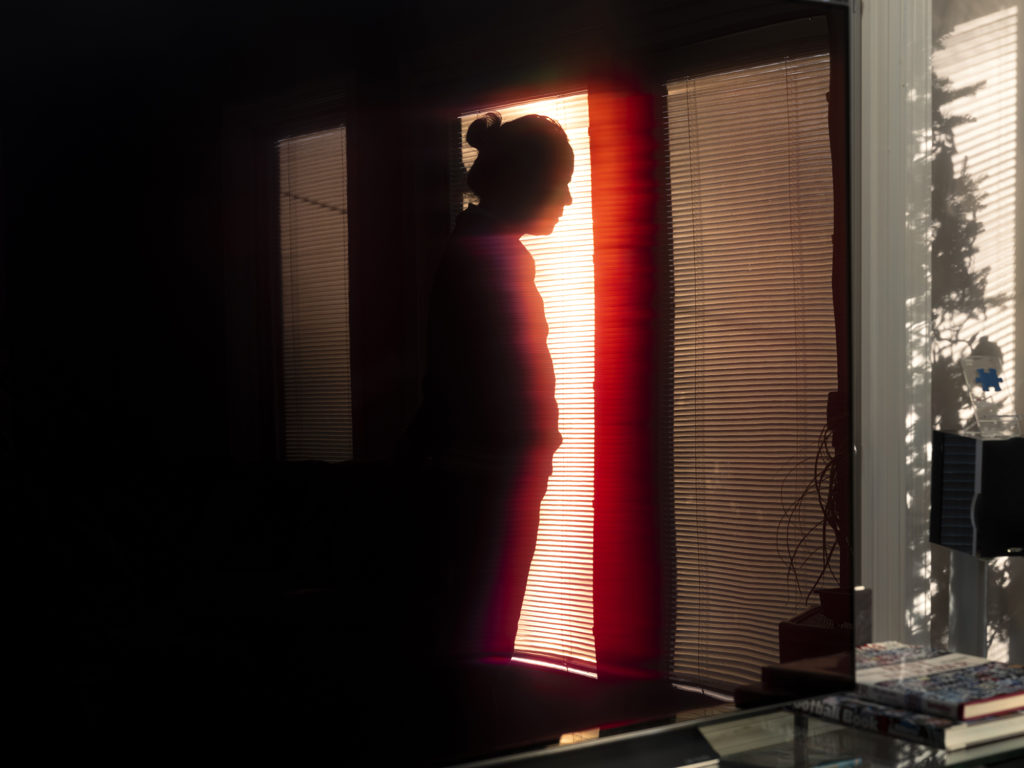

Jarod Lew, In Between You and Your Shadow, 2021, for Aperture

All those clichés that steer the movement of light tend toward revelation: the light bathes, washes, or pools—but rarely does it obscure. In photographer Jarod Lew’s latest body of work, In Between You and Your Shadow (2021), light is both a literal and figurative source of occlusion. A woman in a floral shirt side-eyes the camera, while the gauzy rounds of a lens flare blot out her face; elsewhere, her arms are crossed in repose on a couch, head clouded by a pale blur, as if overexposed into anonymity. This figure is Lew’s mother, both the series’s inspiration and, along with his family, its reluctant subject. She does not like being seen, Lew tells me, which was the project’s core obstacle: “How do you photograph your mother without photographing your mother?”

In the stray refractions of a blazing sun and other such tricks of light, Lew has found a way into his project’s central paradox of visibility: In 2012, he discovered that his mother had been engaged to Vincent Chin, the Chinese American draftsman murdered in 1982 by two Detroit autoworkers days before his wedding to Lew’s mother, a turning point in the history of Asian American civil rights. “I kept coming back to this thought about who my mother evolved into after the killing,” Lew says. “What part of her died when she had to be thrown into the spotlight of the national news?”

Four years elapsed before Lew could confront the weight of this personal and juridical trauma, which led to Please Take Off Your Shoes (2016–20), a project made in the homes of various Asian American strangers in Metro Detroit. For In Between You and Your Shadow, Lew turned to his parents’ home, also in the Detroit area, at first stifled by the etiolated blandness of suburbia, but soon attentive to the narrative possibilities in its banal geometry—a bathroom mirror turned nested frame for his mother’s half-hidden face, or a frosted glass door smudging her familiar features. These corners of the home are vectors as much as props for partial obscuration, as if making a display of her withholding.

At other times, white walls become backdrops for a different form of spectacle. One picture shows arcing lamplight as it pierces the silhouette of Lew’s bearded father, luminous yellow pouring into his shadow. Another contains a glossy Buddha figurine, once owned by Lew’s late grandmother, sitting in a dim corner and dwarfed by its own strangely doubled shadow. I’m struck by the thematic precision of this particular image and its making. Before a happy accident with LED stickers cast these dark and voluptuous shapes, Lew had used a full-on flash but found the image uninteresting. Excess light had stolen its depth.

Many of the photographs in this series bear the stark, flattening clarity of flash for a different reason. “The momentum of this project really started with specific memories I had as a child,” Lew says, “so I recreated them to get my family comfortable with the camera, but also to lead into newer pictures of them that were maybe less staged.” His process began as a kind of conjuring, the studio setup lighting a way into the unspoken densities of his familial past. Some of the earliest shots were images gleaned from the vivid archive of Lew’s childhood: his gym-going father flexing in the mirror; his red-manicured mother’s hand shaving his father’s head. Any other start would’ve made the project impossible, Lew explains. It’s a neat workaround, invoking these unstable fantasias of personal memory, pocked by elisions and revisions, like so much immigrant history. Between a taciturn parent and a cultural identity long patchworked from state-authored illusions, traveling through fiction might be the best way to chance on something like truth.

Lew’s routine dramatizations, in which his brother and Lew himself also make appearances, were enough to coax a certain ease from his parents, their slow-blooming candor opening up a more spontaneous practice. “There are moments when I see light, see how it cuts through things,” Lew says. “I’ve lived in this house my whole life, so I know where to wait.” Most of these impromptu images are marked by honeyed slants of daylight, the sun sneaking through half-shut blinds onto a tiny snapshot of Lew’s mother as a teen, or striating a tender close-up on his parents at dusk. But these radiant intimacies belie one of the project’s thornier realizations.

“Making these photographs revealed this disconnect I have with my parents,” Lew says. “Though we are becoming closer, because we’re playing with one another, there’s still this performance that’s happening, this constant guard between us that I don’t think they’ll ever drop.” Across these staged and mutable frames, Lew has built a way of seeing that centers contradiction, moving past the hypervisibility of racial injury to ask: what does this ubiquity obscure? Necessary mysteries, maybe, or something like gratitude for shadows.

Jarod Lew’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX100S with a FUJINON GF 80mm F1.7 R WR lens.

Courtesy the artist