The Unexpected Photographs Ansel Adams Made before Becoming a Household Name

Mike Mandel’s book “Zone Eleven” presents commercial photographs attributed to Adams. But are they essentially found images that have little to do with his artistic vision?

Ansel Adams, SCUBA Class, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1966

Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

It is difficult to associate Ansel Adams with anything other than sublime, silver-print vistas. You picture him alone beneath majestic mountains, in the shadow of Half Dome at Yosemite, and looking up at billowy clouds through which light streams down to the rocky terrain of California’s Central Valley. There are rarely any humans visible in Adams’s most famous photographs, and so, by extension, it’s easy to think of him simply as a quiet man who communed attentively with nature.

Mike Mandel met Adams in 1975 when the former photographed the latter for Untitled (Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards), Mandel’s witty commentary on the rising status of well-known photographers of the time. This was just a couple of years before Mandel collaborated with Larry Sultan on Evidence, which was published in 1977. That book (and exhibition), composed of found photographic oddities culled from governmental and corporate archives, forged an approach to looking at vernacular pictures that wryly reveal commentary when taken out of their official context. Mandel had the idea for Zone Eleven, a new book that culls out-of-character Adams pictures, back then, while Adams was still alive (he died in 1984).

Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

The size and horizontal orientation of Zone Eleven echoes that of Evidence, as if they are siblings born forty-four years apart, with divergent personalities. Evidence has an ominous, black dust jacket with the title in white, like a heading on a dossier. There is dark humor to that design that runs counter to the cover of Zone Eleven. A crisp, clean white, this new cover features a title in the same serif font in roughly the same position as Evidence’s, only with letters that move through a spectrum of full black to gentle gray.

This range of shades refers to the famous ten-zone system, which Adams codeveloped. The system goes from zero to ten, black to white, as a means of creating optimal black and white exposure and printing. As a title, Zone Eleven (itself containing ten letters!) suggests Spinal Tap’s pumping up the volume to that next level, though the degree of comedic energy to this project is moderate. Ten is the pure white side of Adams’s tonal spectrum; eleven could be something beyond recognition.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

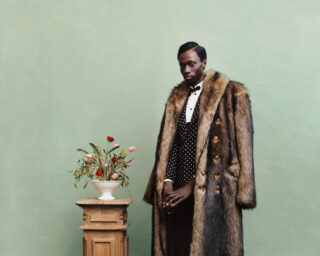

The eighty-three images in Zone Eleven are not masterworks but pictures Adams took for commercial clients before he could survive on sales of his artwork. “These are essentially vernacular pictures that happen to be made by Ansel Adams—totally unlike Adams’s best-known photographs,” writes Erin O’Toole in the book’s contextualizing essay. The latter, she adds, “Mandel terms ‘unitary,’ meaning singular pictures that don’t depend on what comes before and after.” Adams’s name is on the spine (just like Sultan’s is on Evidence), and Mandel, in this quasi-collaboration, is responsible for adding the “canny selection and juxtaposition,” as O’Toole describes it. Mandel, in a no-longer-revolutionary strategy, had combed through archives of some 50,000 images at the Center for Creative Photography and the California Museum of Photography at UC Riverside, most dating from the 1940s through the 1960s.

He chose some outdoor shots of beaches, hillsides, prairies—though these, countering the sublime, seem more like sites of recreation, of beach wading and guided treks up snow-covered peaks. Because these settings are in Adams’s wheelhouse, they’re less surprising than pictures that depict social situations—you realize just how few of his known photos include people.

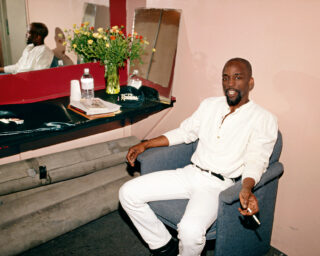

There are crowds, and there is frolic, as in Recreation Center: University of California Los Angeles (1966), a series of six images that capture divers hovering above an expansive swimming pool with smoggy views of Los Angeles in the background. There is wit and magic to the illusion of levitation, to the figures floating, expectantly, forever captured on film.

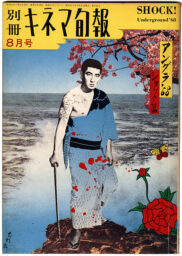

Fortune Magazine Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

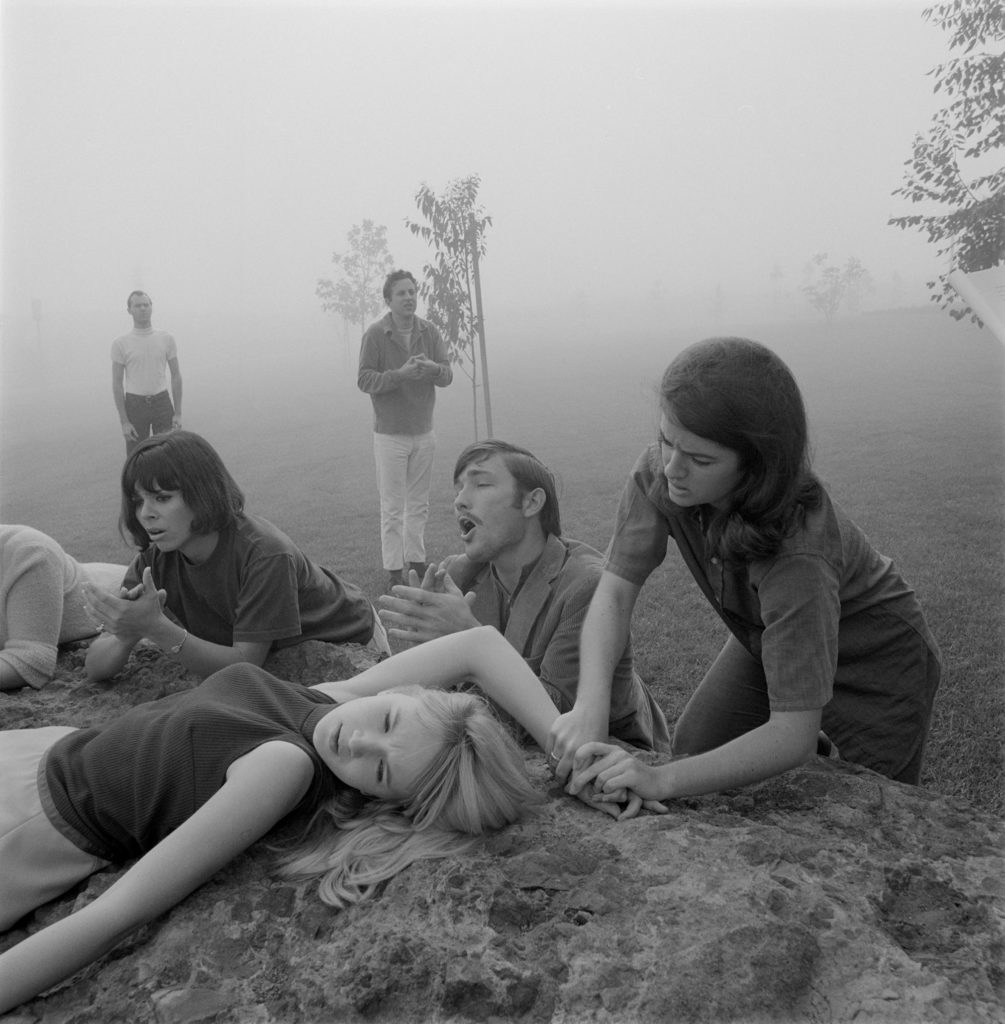

There is a 1928 photograph of a man in diaphanous drag, titled Fun in Camp—the Premier Danseuse, Ernest Arnold, Canadian Rockies. There’s no information provided on the subject, though bearded Ernest looks rather like a demure member of the Cockettes, that infamous San Francisco hippie drag troupe, with his makeshift costume of cheesecloth and wildflowers. Another college scene, Drama Rehearsal, Misty Morning, University of California, Irvine (1966), shows youthful hipsters emoting and reclining on a rock, and while dressed, they seem like precursors to the desert orgy in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point. You just don’t equate youthquake energy with Adams, and it’s heartening to be able to.

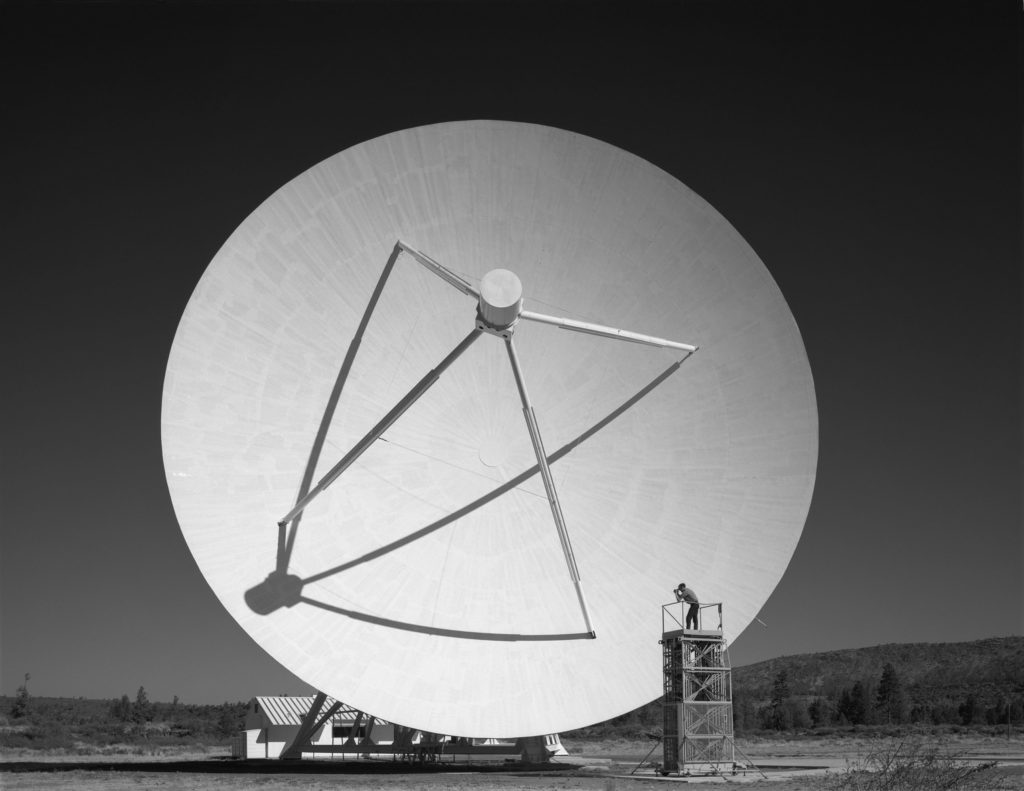

Cole and Dorothy Weston at Home (ca. 1940) shows an ardent kiss framed behind a front-door screen—it’s an amorous winter embrace, and which, surprisingly, comes from the Fortune Magazine Collection archives. Mandel pairs it with Building Through Window Screen (undated), a hazy view of a barn-like structure as seen through a wire mesh panel. The two pictures are linked by domesticity. Other sequences depict shadows on walls, modernist architecture, and scientific equipment.

There was a time when Adams was the most famous photographer working, a household name, and a staple of college dorm room posters.

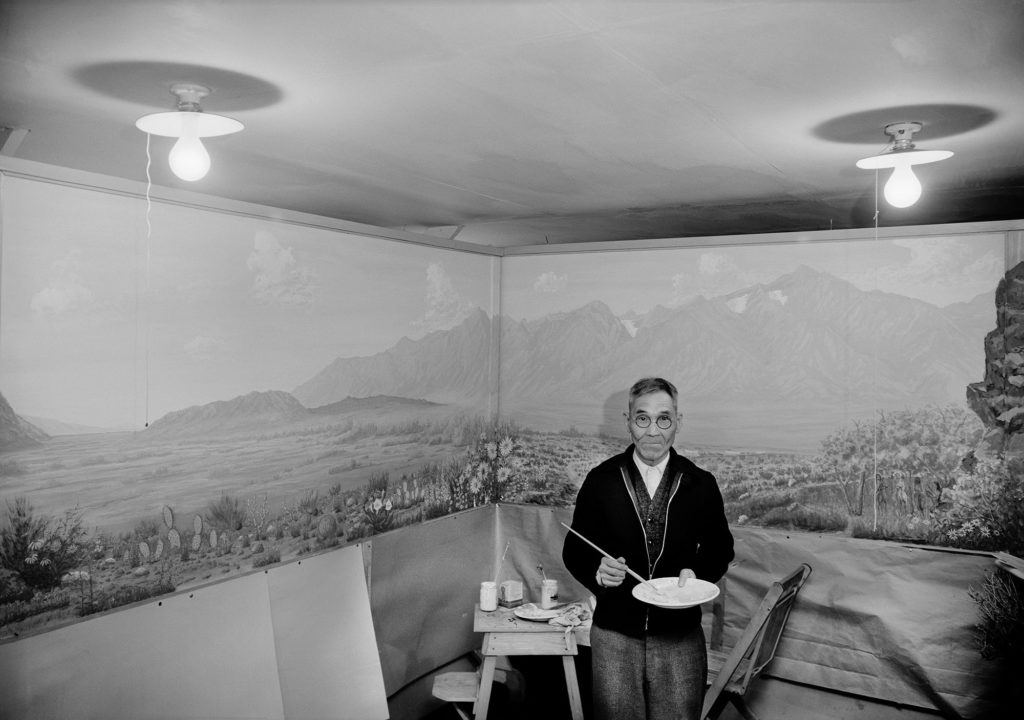

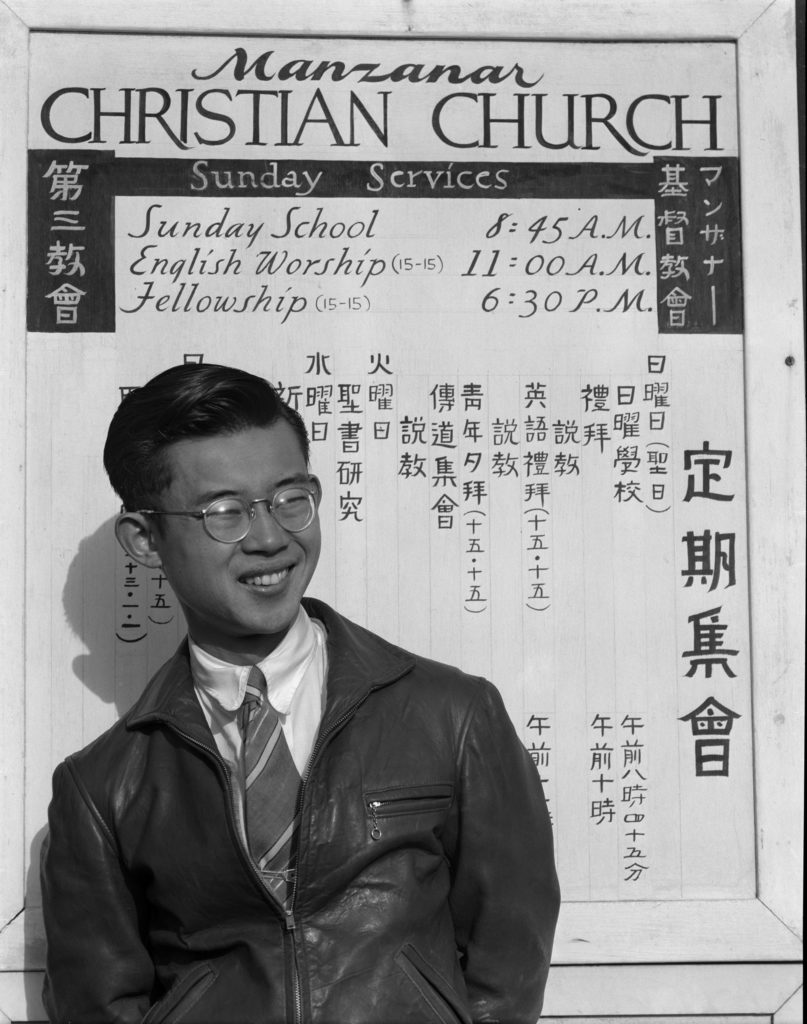

The center of the book features a few portraits of Japanese Americans at the Manzanar internment camp. These are grounded, humanizing images that focus on individuality over strife. Tatsuo Miyake (student of divinity), Manzanar War Relocation Center, California (1943) shows the subject posing in front of a rectangular sign for camp church services. The composition, however, reads something like an identification photo, even though Miyake leans left and smiles broadly. These, along with a few exteriors of the Manzanar Relocation Center, have a more documentary feel, as they offer an on-the-ground view of a politicized site that Adams famously photographed from an aesthetic distance. This sequence also hints at a social conscience that isn’t as visible elsewhere in the book.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Unlike the anonymous photographers in Evidence, here the photographer is an extremely known entity. The images in Zone Eleven are commercial works attributed to Adams, but are they essentially found images that have little to do with his artistic vision? Outside of the Manzanar pictures, they don’t tell us much about the man other than the fact that he actually had ties to civilization.

There was a time when Adams was the most famous photographer working, a household name, and a staple of college dorm room posters. His role in popularizing the medium cannot be underestimated. His focus on glorious natural subjects and his reverence and advocacy for careful darkroom printing and photo education now seem quaint in a world saturated with digital filters and phone cameras, and when instances of environmental catastrophe are the new sublime. There’s a nostalgic sweetness to this project, both in the images and in Mandel’s form of homage. But there isn’t much urgency. Which is to say, if Zone Eleven is meant to provide evidence for reevaluating Adams, it lands pleasantly in zone five.

Mike Mandel: Zone Eleven was published by Damiani in October 2021.