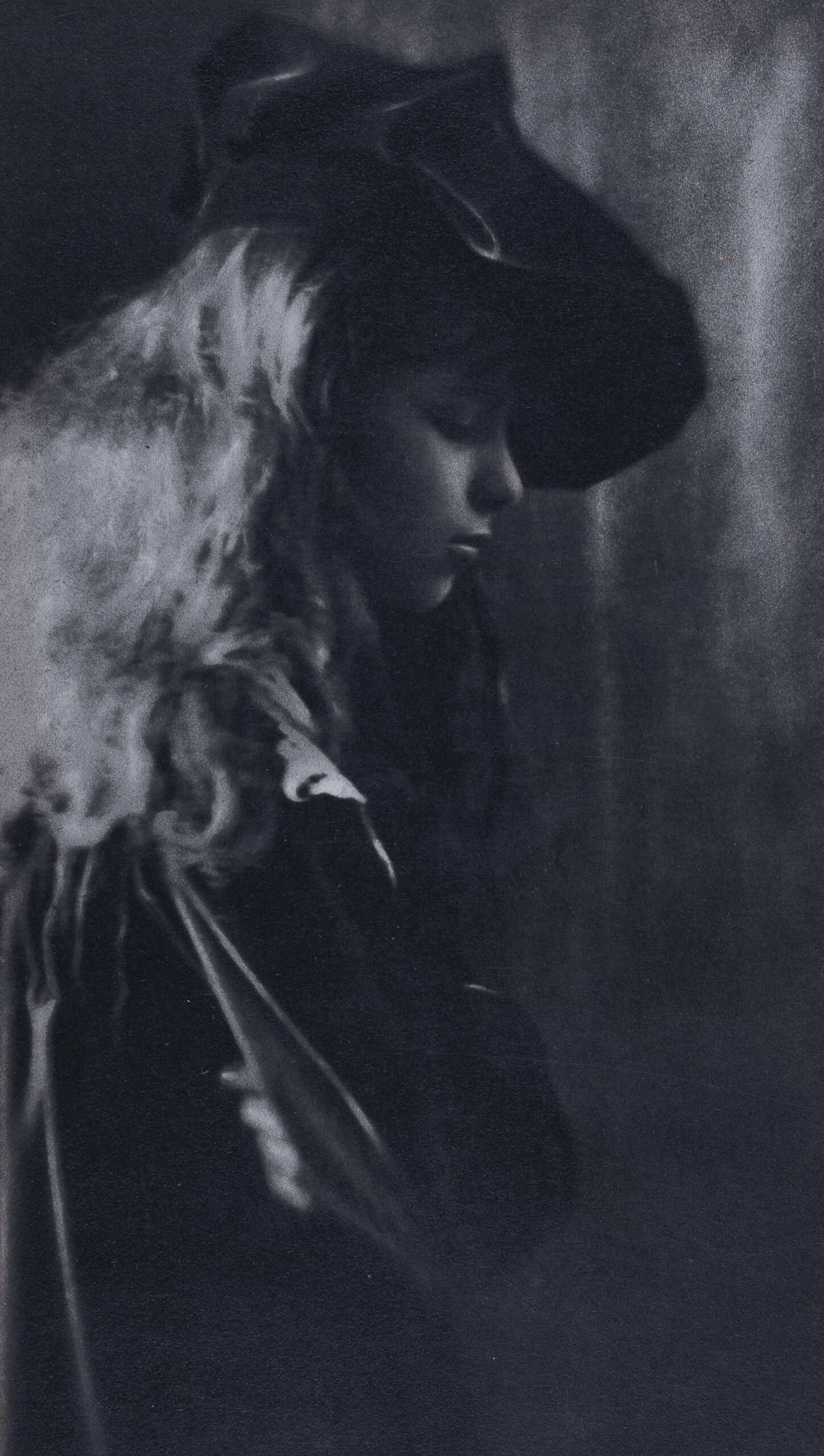

Céline Laguarde, Stella, 1904

In January 1898, the Pictorialist photographer Robert Demachy penned an impassioned panegyric on photography for the monthly Bulletin du Photo-club de Paris at 44 Rue des Mathurins, the organization’s headquarters. “The great mistake photographers make,” he wrote, “is believing that artistic vision and imagination are automatically included with the darkroom. It’s not just the techniques of drawing and painting that artists learn during their many years at the academy.” He ended with a challenge: “We photographers create in a single moment, but how many of us take the time to master the rest?”

The French photographer Céline Laguarde, now the subject of a retrospective at the Musée d’Orsay, didn’t officially participate in the Photo-Club of Paris until 1901, but she proved herself equal to Demachy’s challenge. As a nascent photographer, Laguarde was an ardent student of Demachy, who had helped develop and refine the unique printing techniques she emulated. Her exquisitely preserved prints showcase the development of photography and the darkroom experimentations that followed.

Céline Laguarde: Photographer (1873–1961) continues a theme first explored in Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers?, an exhibition jointly presented between the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie in 2015. While researching that exhibition, the curator Thomas Galifot came across Laguarde’s work in early twentieth-century journals and was struck by the contemporaneous recognition and accolades she had achieved, and her technical ability with pigment-based processes. Her work deserved, Galifot felt, deeper consideration. In the intervening years, Galifot tracked down Laguarde’s personal archive, which he was able to acquire for the museum. The approach to the ensuing solo exhibition was twofold: to present Laguarde as France’s most significant pre-World War I female photographer and, more broadly, as a master of the artistic medium.

Originally from Biarritz, Laguarde and her widowed mother decamped to Aix-en-Provence, in southern France, after a brief stint in Paris. Like many girls from wealthy families, Laguarde was fluent in artistic pursuits and became an accomplished pianist; toward the turn of the twentieth century, she began exploring photography. “Photographic practice became accessible to everyone able to ‘push the button’,” says Galifot. “Snapshot amateurs, men and women alike, did not need any specific training.”

But Laguarde had more than an amateur’s interest, and so the Photo-Club became a home for her to hone her talents. “They accepted accomplished photographers as members,” Galifot says of the organization. “But it played a major role in sharing the knowledge about the complex pigmentary printing processes which were typical of the French school of art photography.”

Armed with new technical prowess, Laguarde began photographing widely in a clear Pictorialist aesthetic. Landscapes, portraits, and studies abound in the exhibition, all in the distinctive sepia tones of the era. The gloriously melancholy women in her portraits, fictional heroines distilled from literature or old master paintings, assume somber expressions with a gouache-like halo surrounding their waist-length hair. In some, like Nitza (Étude en plein air), the pigments drip down the page, as if the bottom of the image had been singed by fire, leaving falling ashes in its wake.

Study after study reveals Laguarde experimenting with form; in the exhibition, Galifot stages a portrait in each incarnation to describe the differences in printing process or cropping. Thanks to the tutelage of Demachy, Laguarde utilized the pigment processes as they developed: first, the gum bichromate process, then the oil process, and finally the oil transfer process. The appearance falls somewhere between paint and charcoal.

Amid a sea of hazy portraits and a multiplicity of studies, a single untitled still life stands out. The only one of its kind in the show—unsurprising, given that Pictorialists largely ignored the form—it’s as if Laguarde captured the flowers mid-death, their heavy heads tumbling down the sides of the crystal vase. There’s a funereal gloom, and yet, as the flowers seem to sigh with strokes of white light, the immaculate beauty of their short lives still shines through: life and death captured in a single moment.

Photography is relatively new to the Musée d’Orsay—a permanent collection was not formed until 1978; a retrospective on any photographer, let alone one whose name is unknown to the public, carries considerable weight. In looking at the 130 prints on view (more than half of the some two hundred prints by the artist that the museum owns), one wonders if the inevitable framing in media and marketing—a woman forgotten, a woman rediscovered—is reductive.

Undoubtedly, gender does play some role here: “She was one of the leading art photographers of France at the beginning of the twentieth century, who deserved [as much of a] spotlight as her very few male counterparts, who considered her their equal,” says Galifot. But the heart of the show lies in technique, something for which Laguarde was justly lauded in her lifetime. No evidence suggests that her gender held back her career. Vitrines showcase numerous publications where Laguarde’s work was featured, and her work was exhibited in her lifetime at world’s fairs and major exhibitions of photography in France, Europe, and the US.

All photographs courtesy Musée d’Orsay, dist. GrandPalaisRmn/Allison BELLIDO

Other female contemporaries of Laguarde also received acclaim, and some of their work is reproduced in this exhibition: Louise Binder-Maestro, Madame Huguet, and Antoinette Bucquet all had similar career trajectories, but sadly their work did not survive the ravages of time. And for all her Pictorialist splendor, the work of Julia Margaret Cameron is often displayed and celebrated, but the techniques, the trials and errors, the cropping and experimenting are rarely shown, and that is where the d’Orsay’s exhibition shines.

The French Pictorialist community collapsed during World War II; aesthetically homeless, Laguarde began aiding her husband’s scientific research with microphotography, and tried her hand at other art forms, including dyeing textiles. It’s interesting to imagine what kind of artistic photography she would have created in subsequent decades had she continued; would she have modernized her techniques along with the times, and begun creating photograms and solarizations? Or would she continue with the processes she loved, and change the subjects? Still, over the course of fifteen years, she left an indelible mark on photography, one that is rightly being celebrated.

Céline Laguarde: Photographer (1873–1961) is on view at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, through January 12, 2025.