The World Is Martin Parr’s Runway

The Magnum legend has fixed his irreverent gaze on high fashion for nearly thirty years—but don’t call him a fashion photographer.

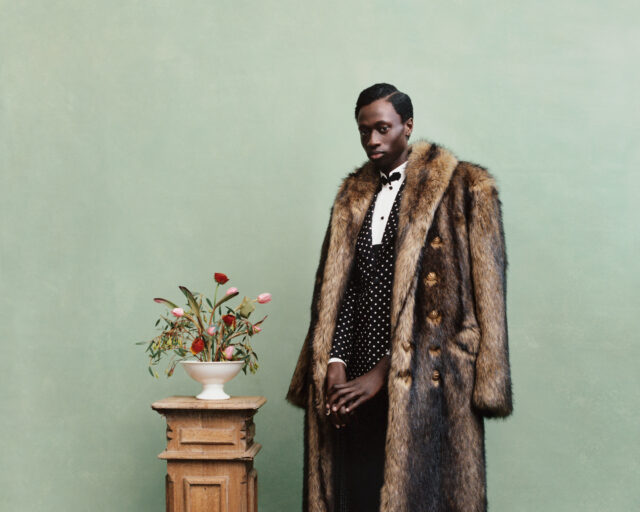

Martin Parr, Fashion Week, Paris, France, 2018. Commissioned by Gucci

The British documentary photographer Martin Parr has long chronicled how people experience leisure and pleasure by interacting with the trappings of consumerism. His depictions of shoppers in Laura Ashley, tourists in beach cafes, and Tupperware parties scrutinized late twentieth-century British life in new ways. His more recent, cropped-in, color-saturated pictures are graphic commentaries on the glorious and hollow nature of manufactured delights. Sometimes, they are discreet commissions by fashion magazines and fashion brands. The Martin Parr Foundation, an exhibition space, library, and archive focused on photographers from Britain and Ireland, opened in Bristol, England, in 2017. I met him there earlier this year to talk about his new book project.

Alistair O’Neill: Good afternoon, Martin. I’d like to talk to you about your forthcoming publication with Phaidon, Fashion Faux Parr, which is the first book dedicated to your fashion photography. How did the book project come about and why now?

Martin Parr: I guess I started fashion in 1999, when I was invited by Amica magazine from Italy to do something, and I thought, “Oh, why not? I’ll just do a fashion shoot.” That turned out fine. Since then I’ve continued to do fashion, more editorial than commercial. In the last five years I’ve had an extra spurt of doing fashion for brands like Vogue and Gucci. It’s been quite a productive period, so it struck me as the right time to show what I’ve done in the fashion world. I think most people would associate me more with documentary, so it’s nice to have this opportunity to show another side of my work. We run the foundation here and the income from fashion assignments, both editorial and commercial, helps to keep this place alive and well, really, because it is twelve people working here and they’ve all got to be paid. And I enjoy doing fashion, it’s fun. I like the idea that you can use photography to solve the problem. You’ve got to basically make an interesting picture. And obviously, people employ me because I’m Martin Parr and I have to make Martin Parr pictures, which is no problem. That’s it in a nutshell.

O’Neill: It is funny though, because that kind of economic model that you just described, where the fashion work helps to support the work of the foundation, it’s not that dissimilar from the way that say, postwar photographers who wanted to be photographers in their own right took on fashion work in order to get the money to produce their personal portfolio.

Parr: I’m not saying this is a highly original way of working. There are a lot of people now in the documentary world who do fashion—Jack Pierson, Harley Weir, and Juergen Teller—to support their own work. And in fact, they try and make it into their own work. That’s the question, whether it does become that. And I guess I look through this and I think, “Oh, this is not bad and I’m happy I’ve done it.” But when I go to the pearly gates, it won’t be the first book I get out.

O’Neill: I can well imagine.

Parr: That doesn’t mean I don’t like it. I’m very happy to have this published.

O’Neill: Let me ask you about the title, it’s a play on words. Rather than faux pas, P-A-S, it uses your surname.

Parr: With Phaidon, we sat down, looked at different titles. In the end, everyone liked it and off we went. So it didn’t take much effort to come up with this. It was there in the first instance, and it survived, and all the others fell away.

O’Neill: But the idea of the faux pas as a kind of misstep or an indiscretion, or something that’s socially embarrassing, when you connect it to fashion it’s very potent.

Parr: Absolutely, all the implications of the phrase really work. I think you’re right, it’s a critique and yet it’s not at the same time.

O’Neill: I think what’s interesting about fashion is that it’s very revealing of us—in that it allows us to project something of ourselves, but it also reveals how that projection sometimes is out of line; or says something that perhaps we didn’t really want to reveal. Do you think that’s something that’s particular to fashion?

Parr: I don’t think so particularly. I mean, I like to go outside into the real world. And when I look through the books of contemporary fashion photographers, they basically seem to stick to the studio. And for me, getting out in the real world, trying to make a real plausible picture that works, that looks interesting is the challenge and that’s what I’ve basically done. I don’t think there’s any shots in the studio at all here. It’s all in the outside world.

O’Neill: In 2005, you published your own fashion magazine, which followed the format of a conventional consumer title, but all the pictures were yours. It even had an editor’s letter, where you said that the boundaries between what’s a fashion editorial and what’s documentary has become blurred, and that there’s something pleasurable about that.

Parr: I still think that’s the case. For example, when I do a fashion shoot, I get twelve pages. If I do an editorial shoot or just submit pictures to do with a recent book, if I get four, it’s a miracle. So this is amazing that you can actually have this work where you can make interesting pictures and get a big spread and get well paid as well. What’s not to like?

O’Neill: So is it about a kind of control that you are able to exercise?

Parr: Well, in the end, you don’t have control. I don’t talk to the art director about which images to use. I’ll make a selection, they’ll go through them and then they’ll request the high-res. And it’s up to them after that, I’m not involved.

O’Neill: But can you ascertain a difference in terms of working with art directors and editors in fashion, as opposed to photography or design?

Parr: Well, they’re more enthusiastic, basically. Fashion people are generally enthusiastic and they all wear black. I mean, that’s two things I can tell you about them that you probably know already.

O’Neill: Well, yes, they do have a tendency to dress in a quasi-uniform.

Parr: Exactly.

O’Neill: And you’re not averse to wearing fashion yourself in some of your pictures. There’s a great picture in that magazine of you wearing a black CP Company jacket.

Parr: What happened was I did this book called Autoportrait, and there was a very good guy at W Magazine, what was he called? Dennis something or other.

O’Neill: Dennis Freedman.

Parr: But I remember Dennis was a really inspirational guy and I did a great spread for him, editorially for W. And then he saw this Autoportrait book that I’d done and he commissioned me. Maybe the one you mentioned isn’t part of that shoot, but he commissioned me to go. He says, “I’m sending you ten pairs of trousers, ten jumpers or whatever, go and have your portrait taken.” So that’s just what I did. That’s a pretty inspired sort of editorial request, I guess.

O’Neill: Well, Freedman was an important editor. He was responsible for commissioning art photographers like Tina Barney and Philip-Lorca diCorcia to take fashion pictures for W. And it’s considered a real high point of fashion imagery in that moment.

I wanted to ask you about an observation you made about going to the Paris shows in 2011, when you were shooting for Madame Figaro and you saw the Dior show just after John Galliano had exited, and a Celine show by Phoebe Philo. You made this really interesting point of comparison between the two shows about lighting. You said the Dior show looked like a poorly lit disco, and that the Celine show was so clean and consistently lit, you could see everything in one glance. And it made me think that some photographers are very much more focused on the smoke and mirrors of fashion as opposed to say, the clothes themselves.

Parr: I hadn’t considered that, but certainly when I go to these fashion shows, the first thing I’m hoping is that where the show’s going to take place is not black because you just can’t really work that.

O’Neill: The other thing about fashion shows is that photography is really zoned. So, you have people at the front of the catwalk who are there to get the catwalk shots—total head-to-toe front looks—and then you’ve got the people backstage who are doing beauty and prep shots. And sometimes you have a roving photographer as a kind of journalist, who might be someone like you. Is it something you try to fight against when you’re in those environments?

Parr: Well, obviously you go to backstage and it’s crawling with photographers, though sometimes less because they’re more picky. And it depends how good your access is, really. It’s a real hierarchical business. I remember when I went with the editor of Stiletto magazine, Laurence Benaïm, she knew everybody. And just sticking with her meant I got in everywhere. But if I go on my own, it wouldn’t be as easy, the access would be limited.

O’Neill: A pass sometimes is not enough, it’s better to be visually recognizable. When were you first introduced to fashion?

Parr: Well, I sort of vaguely knew about people in the fashion world before I started doing it myself, but I haven’t taken it that seriously, really. I noticed in auctions that fashion pictures always got the best prices, which I always thought was interesting. And then I started, and of course I didn’t know much at the beginning, I know a bit more now. But of course, I still say I’m not a fashion photographer, which is really the case. I’m a documentary photographer that does fashion from time to time. And I think that’s the best way to present it.

All photographs courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

O’Neill: I think what you’ve just said—that you are not a fashion photographer, you are a documentary photographer, standing on the outside, let’s say, pointing your camera in to this system, this world. But what this book demonstrates is that you’ve developed quite a prolific body of work in this area. Do you still see yourself as sitting outside of it?

Parr: I think so, yes.

O’Neill: Do you think the boundary has become even fuzzier?

Parr: Absolutely. Same with me and with many other photographers. And the whole business now of how these documentary photographers get drawn into fashion. I think it’s a healthy thing, basically. It’s always good to see a shake-up of the market.

O’Neill: Of course. But it’s interesting that it does only seem to be fashion that has the economic propensity to allow documentary photographers, artist photographers, or others to work in a certain way and still be able to retain a degree of creative freedom.

Parr: Yes, especially editorial. Once you do a commercial, it’s much stricter in terms of they’ve got it all planned out, they know exactly what they want. But with editorial, you do get a lot of freedom.

O’Neill: You have photographed a lot of food in your career. And yet you haven’t had the same inroads in terms of producing food editorial or commercial.

Parr: No, because it always looks too grim, basically.

O’Neill: So you think you make food look bad and you make fashion look good?

Parr: Well, obviously I like junk food, it makes the best pictures. Posh food doesn’t work as well.

Martin Parr’s Fashion Faux Parr was published by Phaidon in April 2024.