At Least They’ll See the Black

Kahlil Joseph, Fly Paper, 2017. HD monochrome digital video and 35mm film with Funktion-One sonic universe. Installation at the New Museum, New York. Photograph by Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

Courtesy the artist and the New Museum

In 1953, the renowned Harlem photographer Roy DeCarava snapped David, a black-and-white portrait of a young black boy from the neighborhood: Hair nappy, his hands are folded behind his back as he leans against a lamppost. A single button holds his shirt closed, and yet the frown he wears allows him to peer, fully represented, directly into the camera’s eye. “He don’t never smile,” observed the Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes when the image appeared in The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a 1955 admixture of 140 of DeCarava’s quotidian images—of black men, women, and children going about their days and celebrated jazz luminaries playing music—paired with Hughes’s narrative. It’s DeCarava’s impressionistic image of black interiority that sits at the center of filmmaker and artist Kahlil Joseph’s film Fly Paper (2017), a monumental, twenty-three-minute ode to black Harlem, past and present.

In Fly Paper’s rapidly moving sequences, you can see DeCarava’s influence in the light and shadow Joseph builds into his portrayal of Harlem as a place of black cultural triumph and loss. Presented last year in a pitch-black installation in the exhibition Kahlil Joseph: Shadow Play (2017), at the New Museum, New York, Fly Paper contains a nonlinear narrative that expands upon the director’s use of the postwar black photographic image to, as DeCarava did, present Harlem as both a real mecca of black America and a fantastic and psychic region of the black imagination. In this way, Fly Paper recalls not only DeCarava’s pictures of black life, but also those of image makers who were part of the Kamoinge Workshop, a group DeCarava led in the early 1960s, including Ming Smith, Louis Draper, Anthony Barboza, and Ray Francis, and other documentarians of black life, such as Gordon Parks, Pittsburgh’s Charles “Teenie” Harris, Dawoud Bey, and Andre D. Wagner. These black artists’ photographs poetically employ light, shadow, and darkness to portray the ordinary and the sublime. Images like DeCarava’s portrait Elvin Jones (1961), of the jazz musician, reveal the varied textures of blackness, and push the boundaries of what can be seen and imagined in the black spaces and faces of a photograph. They are part of a contemporary canon of black images that provide what DeCarava once described as “the kind of penetrating insight and understanding of Negroes which …only a Negro photographer can interpret.”

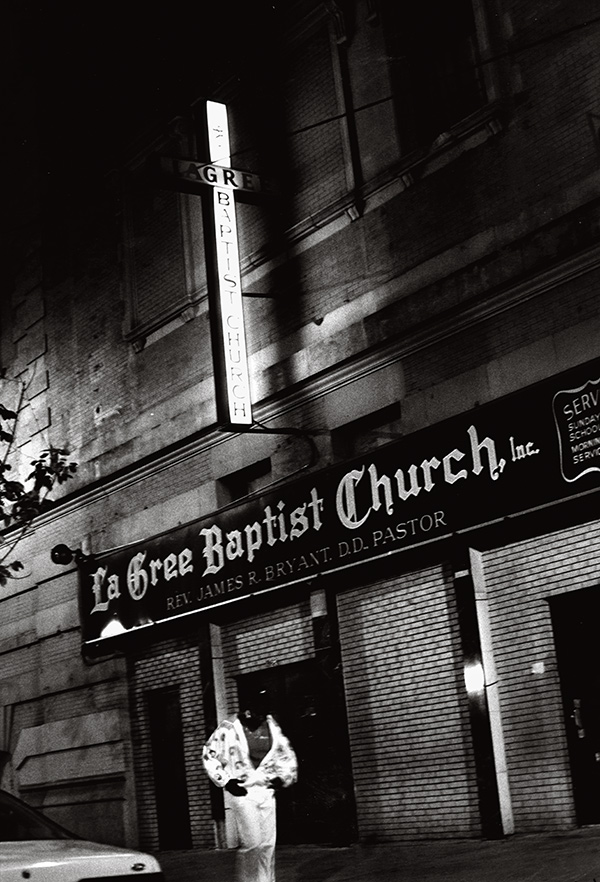

Ming Smith, Lagree Baptist Church, Harlem, New York, ca. 1985

© the artist and courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

“Black people are light-years more advanced than the ideas and images that circulate would have you believe,” Joseph said in 2013, in an interview with Nowness. “The spaces we control and exist are my zero for filming.” It’s a sentiment running throughout his depictions that blends the essence of what DeCarava and other photographers see in black skin and the absorbing fantasy at the heart of the hip-hop music video. Joseph remixes and distorts both media to produce black cinema rooted in the structural photographic. It is like nothing we have ever seen before, because often photography and film center whiteness even in depictions of blackness. As one of the directors of Beyoncé Knowles’s visual album Lemonade (2016), the artist behind Flying Lotus’s Until the Quiet Comes (2012), and the creator of Alice Smith: Black Mary (2017), Joseph uses film as a container to show the multiplicity of blackness by creating small black worlds. Time is suspended, space is distorted, light on black skin is a metaphor, and black music, cut into sounds of salvation, carries the narrative. It’s a cinematic experience that displays on-screen something that mirrors real black life.

This approach is seen clearly in Joseph’s Wildcat (2013), a black-and-white film that makes visible the erasure of the black American cowboy, which largely occurred through Westerns, a genre of film that whitewashed the American cowboy story. Wildcat takes us to Grayson, Oklahoma, during its annual August rodeo, an event that brings African American cowboys and cowgirls from across the Midwest to this small town. In one moment, Joseph’s camera hovers on a young girl wearing a white gown, representing the spirit of Aunt Janet, her late elder who started the rodeo; her eyes are small and searching. These few seconds of film, which appear to upset an entire genre that would have us believe she doesn’t exist, also represent what the gender and race theorist Tina Campt calls a “still moving image.” Wildcat is filled with the stillness one would find in a DeCarava image. There’s no dialogue, a decision that seems to reinforce the idea that Joseph wants us to watch blackness unfold on film in ways we have rarely observed. Guiding us is the melodic score by Flying Lotus, a frequent collaborator of the artist, as we watch contemporary black American cowboys, bull riders, and barrel racers create majestic new images of blackness.

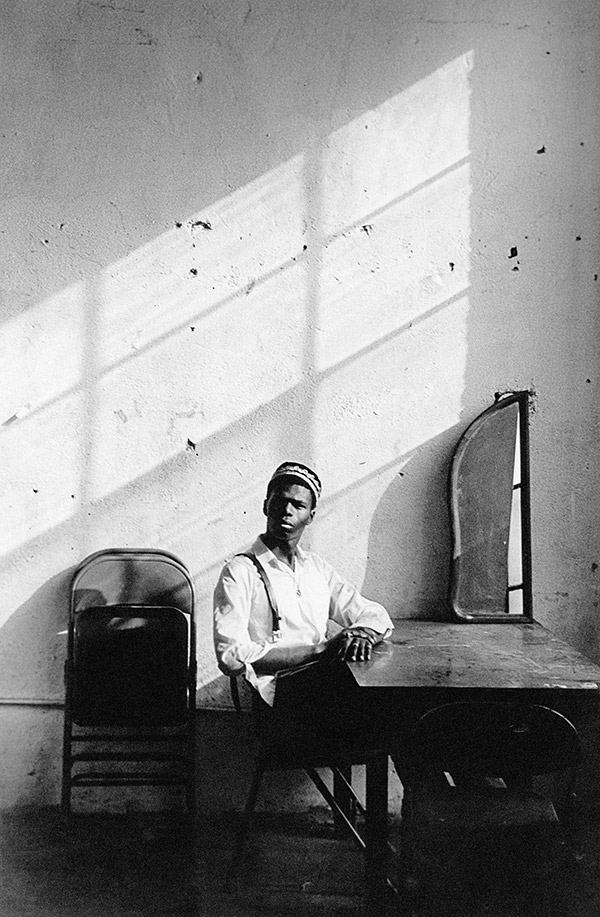

Ray Francis, Harlem, New York, late 1960s, from the book Timeless: Photographs by Kamoinge

Courtesy the artist and Schiffer Publishing

Fly Paper is also filled with scene after scene of black images, retracing bits and pieces of the history of America as it played out in Harlem and the contours of history that placed black people in starring roles. The film opens with the self-determination of civil rights leader Malcolm X as he is delivering a speech on a Harlem street corner. His seriousness brings to mind DeCarava’s famous picture of stony-faced determination, Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, D.C., 1963, and also Parks’s black-and-white portrait Malcolm X Gives Speech at Rally, Harlem, New York (1963). Soon the screen is flooded with mercurial, strange, and ghostly moving images that tease out the complex emotions embedded in black space: the surrealism of Smith’s Sun Ra space II (1978); singer Lauryn Hill jamming; a black mother and child in repose; a dreamlike rendering of the late painter Barkley L. Hendricks’s Lawdy Mama (1969) seen at the Studio Museum in Harlem; black fictive characters, captured in poses that evoke DeCarava’s Dancers (1956), in a darkly lit room flexing in slow motion. At one moment, the legendary performer Ben Vereen lies in a bathtub, fully clothed. These short sequences collide with the bombastic and disorienting sounds of drums, Harlem’s trains, the hustle of 125th Street, and melodies Joseph skillfully turns inside out. Joseph’s personal home videos fade in and out too. We meet Joseph’s father, Keven Davis, gossiping on the street with hip-hop pioneer Fab 5 Freddy, and after surgery at home in his uptown New York apartment before his death, at the age of fifty-four, in 2012. Joseph’s mixing of his family videos with newer original footage is reminiscent of the artist’s m.A.A.d (2014), a fourteen-minute film he made for Kendrick Lamar that blends the rapper’s personal home videos with fresh scenes of his native Compton, California.

“I wanted people to feel like they saw a Harlem that they can’t see,” Joseph recently told the New York Times. He achieves this by showing what another of Joseph’s influences, the artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa, calls “the power, beauty, and alienation” of black Harlem. Jafa believes Joseph achieves his humane representation of black sociality because “he’s self-authorizing. He’s not waiting for things to become canonical,” Jafa said last year before an audience at the New Museum. “I would say I have a little of this as well. If we like the shit, it’s in the canon.”

Kahlil Joseph, Still from Fly Paper, 2017

Courtesy the artist

In 2016, Jafa created the film Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, a tour de force that, like Fly Paper, reimagines the possibilities of narrative, sound, and movement in the construction of the moving image by relying on the black photographic, hip-hop music videos, and memory’s ability to create montage. Jafa’s Love Is the Message draws on a two-decade-long photographic study into what the filmmaker, who was the cinematographer for Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) and Spike Lee’s Crooklyn (1994), calls “black expressive modalities,” which resulted in two hundred notebooks of cataloged clippings of images from magazines of black athletes, entertainers, and ordinary people in motion. In twenty-four frames per second, soundtracked to an elongated mix of Kanye West’s 2016 rap gospel “Ultralight Beam,” Jafa seamlessly pulls together disparate images of violence and creativity. Before our eyes appear samplings of clips from YouTube of black voguers dipping, dash-cam video of Walter Scott being gunned down, former president Barack Obama emotionally singing “Amazing Grace,” LeBron James, Nina Simone, and black-and-white B-roll from his 2014 documentary Dreams Are Colder Than Death and Joseph’s Wildcat.

“How come we can’t be as black as we are and still be universal?” Jafa asked, in 2016, after the release of Love Is the Message. “How come we have to refuse who we are in order for someone to be able to identify with us? How come the audience can’t see themselves in that thing, whether or not it looks just like them or not?” He said, “It’s what black people do because most of what we see are white people. It’s what women have developed the muscle to do because mostly what they see are men. It’s what gay people are able to do because mostly what they see is heteronormative stuff. It’s a muscle that everybody needs to develop: the ability to see themselves in someone else’s circumstances without having to paint that person white, make that person straight, or a man.” Jafa added, “I’m trying to make my shit as black as possible and still have you deal with my humanity.”

Arthur Jafa, Still from Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome

In the final sequence of Fly Paper, the sound of a woman’s voice, lifted from photographer and filmmaker Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983), makes a declaration. As the screen flickers black, and the sound of striking lightning crashes, she says, as if responding to Jafa, “If they don’t see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black.”

Fly Paper and Love Is the Message are works of black cinema that use available images of blackness in film and photography to probe the lack of full representations of blackness in the frame and on the screen. When Jafa presented his film in a recent solo exhibition, Arthur Jafa: A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at the Serpentine Galleries, London (2017), he displayed the photography of Ming Smith as an exhibition within an exhibition that showed, as the art historian W. J. T. Mitchell observed in his 2005 book, What Do Pictures Want?, that black pictures, like all pictures, “arise in all other media—in the assemblage of fleeting, evanescent shadows and material supports that constitute the cinema as a ‘picture show.’” Joseph’s Fly Paper is a new kind of picture show, one using the still black image to help us see more.

To continue reading, buy Aperture, Issue 231 “Film & Foto,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.