Thomas Boivin’s Sensitive Exultation of a Parisian Neighborhood

For the past ten years, the photographer has wandered the streets of Belleville, creating quiet images that reflect on a city that both changes and doesn’t.

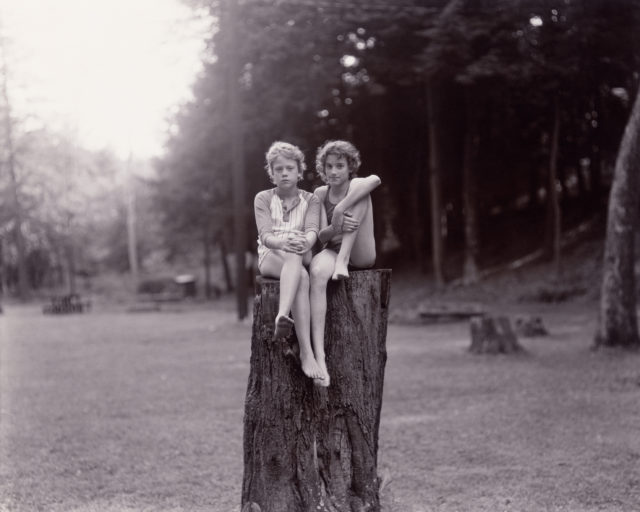

Thomas Boivin, Belleville, 2022

The first time I look through Thomas Boivin’s book Belleville, I try to find the places I know. Belleville is a neighborhood in northeastern Paris, and Boivin made these black-and-white photographs while wandering its streets. I live on rue de Belleville, behind a shop called Bazar de Belleville, which gives the book’s presence on my table a certain Being John Malkovich quality. Immediately I spot the area’s two parks, a certain plumber’s shop front, the hard-to-describe atmosphere of particular points on certain streets. I linger longest on the exterior of the print shop I visited recently for a passport photo, which the employee took in a simple studio in a corner at a cost of €5.50. Boivin’s image centers a side window whose awning guarantees the use of “Kodak-quality paper.”

This text is in both French and Chinese. Belleville is home to one of Paris’s two major Chinatowns, just one community within a patchwork of cultures: Belleville is also more ethnically diverse than almost any other neighborhood in the French capital. To walk down any side street is to pass through several micro-districts that often seem to comprise little more than a shop, café, and bakery, yet feel as though they embody some long-since-settled wave of immigration. The portraits in this book, of strangers Boivin is drawn to, reflect this intricacy but are not essentialized by it. A woman lies on a defunct fountain, reading a novel. A man in a polo shirt and blazer clutches an uprooted plant in Buttes-Chaumont Park.

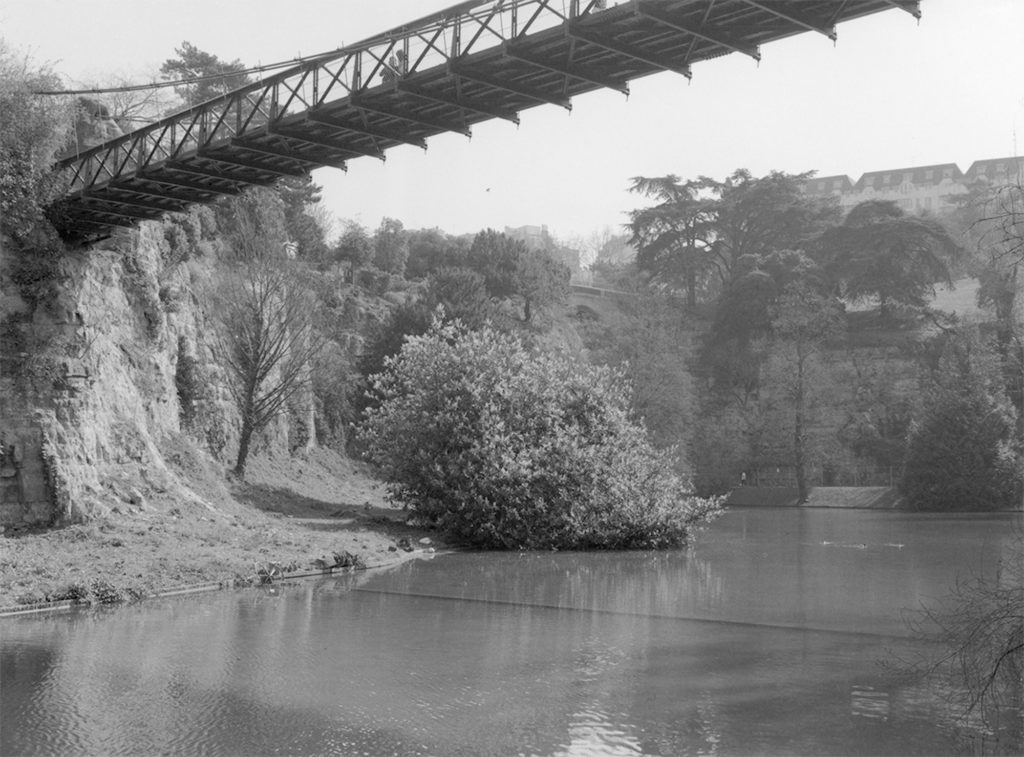

The second time I look through Belleville I am struck by the stillness, a sort of ghostly silence, that seems to emanate from each photograph, even when people are present. Perhaps this is to do with a certain tonal quietness and Boivin’s aversion to black and white extremes in favor of the middle grays. Or perhaps it stems from his preoccupation with what one could call nonspecific places: a flower bush obscuring a drain, a faded curtain in an anonymous window, tree tendrils on an unplaceable fence. The result has a woozy or hallucinatory quality, as if we are slightly removed from reality. Despite spanning a decade’s work, these fifty-five images, shot on film, feel indifferent to the passing of time. Occasional clues—a bus ad for a 2020 Man Ray exhibition, say—seem merely part of the cyclical flow of a city that both changes and doesn’t.

This is not really a “portrait” of a neighborhood, as some might yearn for. In a statement released with the book, Boivin says: “Although the photographs hardly depict the city, I find they convey the sensation that I had, walking the streets of Belleville.” What is meant by “the city” here, as something that is hardly depicted? Crowds? Belleville is densely populated even by Paris standards, a fact far from evident in this series. Or perhaps Boivin refers to crowd pleasers, such as wider street scenes, emblematic locations, Haussmannian architecture, or other easy tropes of street photography.

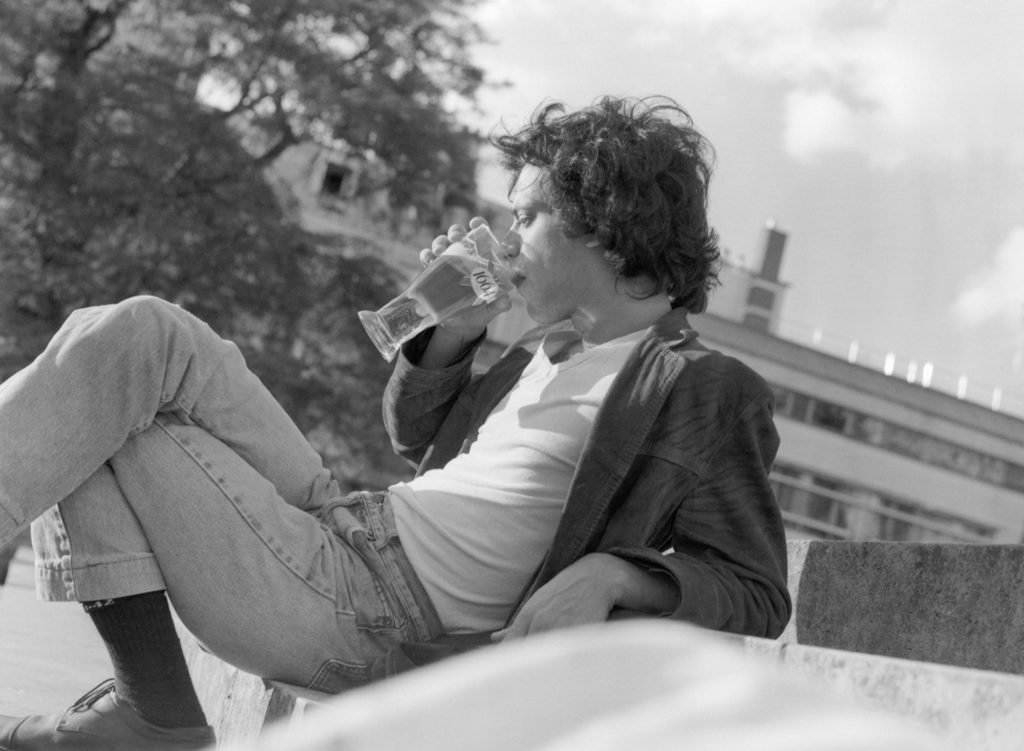

Before looking through Belleville for the seventh or eighth time I cycle to the gallery Les Douches by Canal Saint-Martin to see an exhibition of Boivin’s work. While it overlaps somewhat with the book, the show takes a different approach, with almost none of the images featuring people. Where they do appear, they are presented less as subject than as circumstance: a man holds a melon, a woman stands in front of a set of old windows, and each person’s head is cropped out of the shot. Boivin also likes food and drink, and several images nod to the still-life tradition: a half-drunk carafe of water on the table in an empty bar. A lemon squeezer in a shard of light on a kitchen table. Piles of grocery delivery boxes, wrapped in enough cling film to make your recycling efforts seem futile. And the titles always assert a location—either Belleville or somewhere in its immediate vicinity: Melon, Belleville (2019); Serviettes, Les Lilas (2019); Petit Déjeuner, Ménilmontant (2014).

A sense of place is more potent when sublimated into something else entirely. Belleville often seems less about questing for the essence of its titular neighborhood than attempting a personal exaltation of the ordinary. It simply makes sense that this occurs where the photographer happens to live. Georges Perec’s term infra-ordinary feels relevant to the preoccupations at play here, as does his famous quote: “What we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms . . . Describe your street. Describe another. Compare.” Perec, I should add, grew up in Belleville, near the pond that dominates the second image in Boivin’s book. It certainly appears that there is something ordinary in the local water.

Thomas Boivin: Belleville was published by Stanley/Barker in April 2022.