Between Dusk and Dawn

Tobias Zielony captures the colors and moods of Ukraine’s queer nightlife.

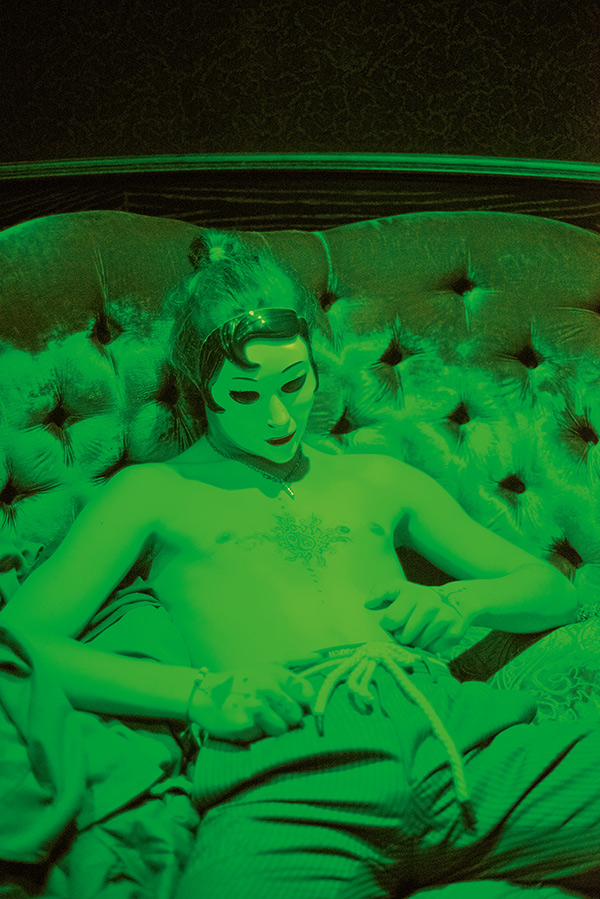

Detail of Tobias Zielony, Shine, from the series Maskirovka, 2016–17

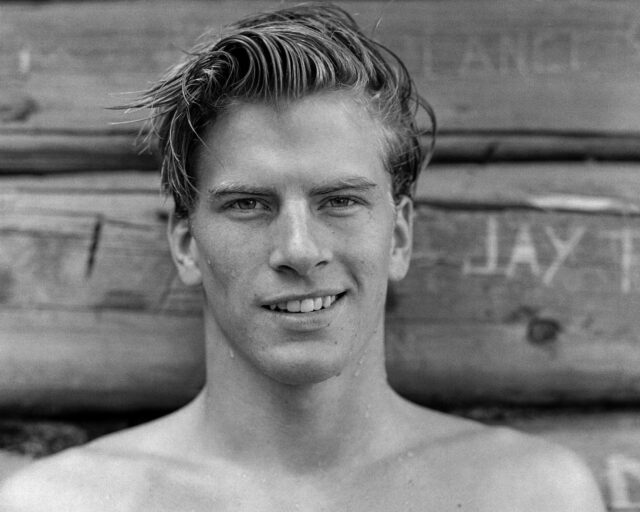

Tobias Zielony’s work offers a lingering, sidelong view at communities at the edges of society. His images blur boundaries between documentary and fine-art photography, offering ambiguous, often fragmented scenes. Standing apart from documentary photography, Zielony, who was born in 1973 in Wuppertal, Germany, nevertheless directs his gaze at the apparatus of that form of storytelling. In Maskirovka (2016–17), a recent project made in Kiev (also spelled Kyiv), Zielony photographed the LGBT community living in the wake of the 2014 revolution. Maskirovka recalls Zielony’s early projects depicting youth, but it has a strong political undercurrent, as working in Ukraine allowed him to examine the current state of Europe. The project also became a mode of exploring the remaining possibility of underground culture, in an age where social media offers illusions of connectedness.

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

Zielony is a talker: He is informed and gets involved, often spending significant time with his subjects. He integrated himself into Kiev’s LGBT scene with the help of Tasia, an activist who is also part of the techno scene, whom he met at a workshop in Germany. In the monograph of Maskriovka, published last year, Zielony included extensive interviews as a companion to his shadowy photographs of these isolated figures with gazes askance, peering into a mobile phone, smoking a glowing cigarette, or standing on a threshold. He is interested in stretching the space between reality and the way it is depicted, communicating other forms of truth. I recently spoke with Zielony at his studio near Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin.

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

Camila McHugh: In your recent Maskirovka project in Ukraine, as well as subsequent projects in Latvia and in your hometown of Wuppertal, you’ve returned to photographing youth culture. You have photographed many young communities, often on the fringes of society, in the past—in Winnipeg, Canada, in 2009 and in rural California in 2008, for instance. What was it like returning to this sort of work?

Tobias Zielony: Well, the project in Ukraine was looking more attentively at political issues, but it is true that I hadn’t done a project on youth or underground culture for some time. So it was interesting to go back and see how much youth culture had changed, particularly in terms of fashion and social media. After photographing in Kiev, I photographed in Riga and Wuppertal, and it was so surprising how similar a lot of things are, especially the fashion. I was struck by how quickly this kind of mirroring is happening because of social media. There was something particular to Kiev, a sort of remaining underground feeling, which I don’t think you find many places anymore. We haven’t had it in Berlin for a long time. I think it is because in somewhere like Kiev, the community is politically and culturally isolated from normative society. Somewhere like Berlin, the boundaries have been blurred for a long time. It also felt like this culture hadn’t been commercialized yet in Kiev, at least during the moment when I was there. The underground community was more of a necessity or a matter of political resistance, so that felt very unique, and also quite warm, in terms of a sense of bonding and solidarity. But it may have begun to change already; I haven’t been back.

McHugh: How do you feel about documenting youth culture now that you’ve noticed this mirroring and other ways in which social media has affected young people?

Zielony: These shifts will inevitably affect the sort of work I am interested in making. Looking at youth culture wasn’t the main purpose of my work in Kiev, but it did make me think about what my role as photographer really is. It is an interesting dynamic, when people like my photos, but they aren’t perfect Instagram material or don’t quite fit the mold of what they consider cool. I often gift my photographs, and twenty years ago people would put them on their wall, but now they put them on Instagram the same night. And so their reaction is more immediate—you see what images people choose to post or like. And then people also started putting filters on the images. There was a guy in Riga who put this analog filter on my digital image with dust specks and everything. But instead of getting mad, I actually think it’s interesting. Or people crop or whatever, saturate the colors. But still I think—if I’m not really doing the coolest or most fashionable thing, it’s probably because I have a different role. You could say I transport a kind of aesthetics or political or cultural situation into a different context, like the art world, but I don’t know how different those contexts are anymore. The context of the art space and the social media space and the actual club—I don’t think it is so easy to distinguish between those spaces anymore. So I think it’s more about seeing connections and communicating my own experience. Or looking at something very specific, like the ideas of masks, which I focused on in Kiev. And then there is also the question of what audience I have in mind. Do my images from Kiev somehow make sense on some level to an audience in London or New York or Berlin?

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: There is a nostalgic click on some level for people in Berlin, like a yearning for what they imagine Berlin used to be. Or in London, as well, for the ’90s of early Wolfgang Tillmans, for example.

Zielony: I think that’s happening. There is a sort of desire in both directions. People all over the world, though maybe especially in Ukraine and Russia, are looking at this ’90s club culture and aesthetic and they’re copying it. Berlin is kind of the ultimate desire and ultimate cool for them. And then here in Berlin, people feel like things have changed so much and they want to return to the sense of community and wildness of a real underground scene, like the one in Kiev, for example. So there are different perspectives or forms of nostalgia at play. My work ends up positioned between those yearnings.

McHugh: As you mentioned, your work in Kiev also directly addresses the political situation there after the 2014 Ukrainian revolution. You titled the work Maskirovka, a term for a Russian military tactic of deception. How did you begin to think about the situation in Ukraine, and your work, in conversation with the term?

Zielony: Maskirovka is a term I was aware of even before the project began, but I came across it again in some research I was doing about masks in Ukraine. Tasia, one of the women who appears in the photographs and who I also interviewed for the project, noticed my interest in masks and began telling me how prevalent masks are in the Kiev party scene. I looked into it further and found that during the so-called Maidan revolution, people were wearing masks most of the time for protection from tear gas, smoke, and so on. And some people were even wearing fancier or funny masks, like medieval helmets and stuff. These masks became sort of a weird, popular, Pop art kind of thing in the face of violence. So in noticing this phenomenon of disguise, I began thinking about the word maskirovka. It’s a Russian term and there are lots of famous examples, like the disruption of the Prague Spring of ’68 and more recently the occupation of Crimea, which began in 2014. When Russia occupied Crimea, they sent special forces in green uniforms without any Russian insignia. Despite the lack of identifiers, it soon became evident that this was a Russian intervention, but by the time there was enough consciousness of what was going on to react, it was already done. This was followed by the conflict in eastern Ukraine, a proxy war that had not been declared. People also use maskirovka to refer to this hybrid state of undeclared, but evident, war or occupation.

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: Titling your project Maskirovka draws attention in part to the phenomenon of the masks: a few of your subjects appear in the masks that Tasia mentioned are popular clubbing accessories. What significance does this notion of a hybrid state have with regard to the work, or Kiev’s LGBT community?

Zielony: I suppose I’m playing with the possibilities of the term as a metaphor of sorts, but this hybrid state of undeclared war is also an everyday reality for the subjects of my photographs and for everyone in Kiev. Everybody is somehow involved in the war—as a volunteer soldier or a medic, or like Vicky, who I interviewed—she is a therapist who deals with people who have been traumatized. And then obviously everybody has someone close to them who was hurt or killed. Kiev is hugely affected, the wound of the war is present, the signifiers of tanks and people in uniform are there, but people hardly seemed to speak about it and no actual fighting is taking place. And it’s not clear when or how anything will change. If you look at the queer community specifically, it is also a strange situation, as Ukrainian leadership has made some moves toward tolerance: the police were protecting Kiev Pride instead of beating up participants this year, for instance. But then it’s dangerous to kiss or act out in the street. This creates a situation where people cautiously move between openness and hiding. A mask becomes an apt metaphor there, too.

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: Your work is presented in an art context, but requires significant understanding of a political and cultural situation. You published a series of interviews with some of your subjects as a companion to the photographs, and the project took place in the wake of mass media coverage of Ukraine. You also studied both documentary and fine-art photography. Do you see your work as a hybrid of the two?

Zielony: Well, first it is important to say that the same photograph can have a different meaning depending on the context it is seen in. As you said, my work is intended for an art context, but also occasionally is presented editorially, like this work in the pages of Aperture. My strategy does have roots in something perhaps more editorial, that sort of storytelling. I’m kind of exploring that tradition—more like investigating the possibilities and limitations of that form of documentation, rather than really participating in it. It is kind of a referencing, in a sense.

McHugh: I noticed a similar motion in your interviews as well. By interviewing a fixer, for instance, you utilize a mode of sort of turning the lens toward the journalistic apparatus, as opposed to participating in it.

Zielony: Right—I am definitely not a journalist. There are a lot of journalistic standards that I’m not interested in participating in: I don’t feel obliged to tell the real story or the whole story or, on some level, even the truth. But there has to be another kind of truth in my work or, like, a lot of different truths. It’s not that I want to lie; the image has to be connected to my experience and the experience of the people around me.

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: Right, I noticed that—similar to the sense of a glimpse into the edges or periphery of a world that I get from your photographs—your interviews also give space to narratives that remain outside of typical news media documentation. Like when Vicky spoke about exhaustion as a major effect of revolution, for instance.

Zielony: It’s so difficult to understand what’s going on and find the right pictures or the right words for it or whatever, so it’s interesting that everybody has their own theory. But I do think it is important to find words or images or characters, because otherwise you leave the higher powers to do the defining, whether it’s Russia or the Ukrainian government, and you don’t want to let them do their thing without any room for being able to describe or criticize what is going on.

McHugh: How do you see the role of photography in facilitating that form of definition?

Zielony: There is a relationship between reality and what comes out of it on an image level. And it’s all about this relationship basically, what’s happening in between, and what role photography or the camera plays in that process. At the moment, with the advent of Instagram and so on, what’s happening in “reality” and what photography is, are increasingly fixed together. I’m interested in what photography can do while maintaining some sort of space or distance from reality. That disconnect, almost. So when people ask me, it’s easier to say I’m a photographer, because it’s an easier way for them to understand what I’m going to do—I’m going to take photographs—but the way I think and build my life is more the life of an artist. I find that I am in kind of an in-between position, between the art and photography worlds, and it’s not very comfortable, but I think that is what photography is about. Or can be about.

Tobias Zielony’s work was featured in Aperture issue 229, “Future Gender.” His photobook Maskirovka was published by Mousse in 2017.