The Artist Remixing History, from French Gardens to the Cosmos

Todd Gray knows history. He has made some himself: his current body of work draws on his time as a commercial photographer, shooting album covers, celebrity portraits (famously, he was Michael Jackson’s personal photographer), and live concerts. He also knows the bitter stories of colonial conquest in Africa—how privilege and ideas of landscape and painting feed pernicious narratives, prop them up—and how photography also serves in power’s toolkit. He knows art history too. When we spoke recently on a bench outside the Pomona College Museum of Art—where Euclidean Gris Gris, his shifting, expanding exhibition of new and recent work, is on view—Gray noted that Helene Winer was once director there, before she moved to Artists Space and helped Douglas Crimp mount Pictures in 1977. Gray was a contemporary of the Pictures artists, he tells me, but he was never one of them. The reason? The gris gris of his title.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Travis Diehl: I want to start with the squiggly, abstract wall drawing, Gris Gris (2019), and how it relates to the photographs.

Todd Gray: Well, let’s see. I envision the whole exhibition almost like kudzu, this organic thing that grows and morphs and surprises me. I usually come here once or twice a month, and I’m just sort of drawing. And then if a student comes, I go, “Hey, you want to pick up a piece of charcoal?” It’s an individual activity that can also incorporate others. The photo works are very specifically mine. That contradiction, to me, is the “Euclidean Gris Gris” of the show’s title. There are pieces that specifically come out of the thought process and determination of the artist. And then there’s this other component that, in its purest form, is pure experimentation.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: This drawing makes me think about the formal qualities of the photo installations—the degree to which the images are abstract or representational.

Gray: I was in South Africa at Nirox, a World Heritage Site with the oldest forensic evidence of mankind. And I thought, you know, I’m of African descent. How can I connect to this place? How can I go past my Western European–American education and culturalization, and create form, and express? And that’s when I said, Okay, cave drawing. Really simple marking. I got into photography because I couldn’t draw. Photography gave me pictures. So the only thing I felt comfortable drawing was a circle. Over a couple years, these circles have morphed into a practice, but it’s not a practice that I control. It’s something that I let occur, spontaneous and improvisational, in the moment. I surrender to that.

Diehl: Is that how you think about the collage or superimposition of the images in the photo-based works too?

Gray: Not at all. The photo-based works come out of a thinking process. The drawings, if they come out of a thinking process, they fail.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

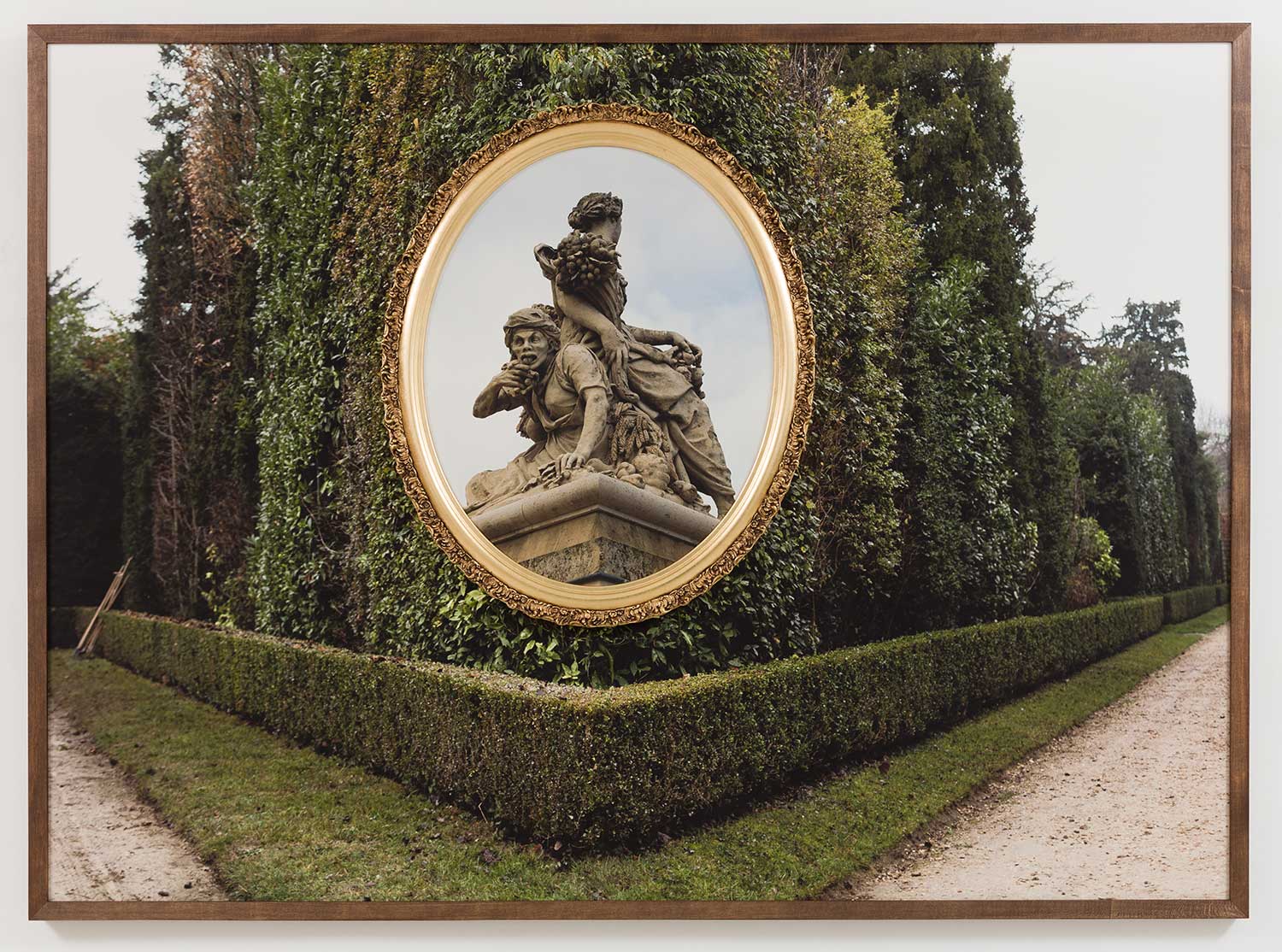

Diehl: Your frames look like frames for paintings. How does painting relate to the photographs that you put in them?

Gray: Painting is privilege, right? That goes back to my investigation of imperial gardens and their relationship to monarchy, or—for lack of a better term—the historical one percent. I was using those big, gold rococo frames to point to ideas of privilege, wealth, class.

Diehl: Yes, those things overlap in your photo-based works. The French garden is also a rectangle, and you contrast these perpendicular systems of control to jungles or mangroves, or oval frames. Just to harp on the formal qualities a little bit more—photography is also a European invention. It’s a rectangular format. Its rectangular logic comes out of the same moment as these kinds of angular gardens, and constructed ideas about nature. I wonder how you think the medium of photography relates to these systems of knowledge that you’re using it to depict and explore.

Gray: Well, I’m a student of Allan Sekula. It’s funny—Allan affected my humanity more than he affected my art. It was only after studying with Allan that I saw photography as an instrument of control. Photography is a way for power to have a direct line into subjects, into us, into the masses; to formulate narratives that we don’t question, because we think these narratives are something called reality. But Stuart Hall thinks that we cannot overcome this immense hegemonic power, and our only power as individuals is to be in a constant state of resistance. I use this thing called beauty in the work to attract a viewer, and then the semiotics start taking place in contrast to the seductiveness of the picture.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: The way you superimpose images resists that seduction too. You have a lush landscape, and then you have this kind of interruption—a superimposed, partial portrait in an oval frame. Or vice versa. It’s pretty jarring.

Gray: The way I use space and perspective, your mind is getting mixed messages as to how to interpret the picture field, and then you become conscious that you have to make a decision. I’m not offering up a pictorial solution; I’m offering up a pictorial problem. I’m hoping that I can reveal the plasticity of photography and the necessity of a viewer to actually create meaning. Like Allan said, you need a caption to anchor a picture. I’m trying to really blow that up. My work is super captionless. I use one photograph to destabilize another photograph to hopefully make you more aware of how unstable photography is.

Diehl: In your work, it’s not simply an abstract idea of jungle versus an abstract idea of garden, or nature versus culture; your images are more specific than that. How important is it to locate those photos in a particular place?

Gray: I want to have macro-conversations, larger-view conversations. Which is why I use pictures of the cosmos. We’re fooling ourselves when we think we can control nature, control humans, control everything. It’s absurd. That’s why we’re facing global warming and the possibility of self-extinction. There’s one installation where a picture of a fire in Cape Town is covering a statue—like I placed it on a plinth, like a trophy. That’s a highly cynical image for me.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: A moment of iconoclasm.

Gray: We can make a rationale for any action, and we can use logic to solve any problem. Even an atomic bomb—we can rationalize why we should use that. And we can rationalize slavery. Years ago, I just thought, Wow, this system of thought is highly corruptible and highly plastic and can do anything, and so I gotta look at other ways of thinking. I gotta think with my body, not with my head. Which is odd because that’s this modernist idea of the noble savage. I was taught to be cautious of these modernist notions. But now I’m saying, It’s more complicated, there are more parts to this machine.

Diehl: To your title—Euclidean geometry is an idealistic, geometric way of ordering the universe, and a gris gris is a talisman, something more shamanic and intuitive. It seems like art fits into both sides. It’s that combination.

Gray: Art is the clearest way for me to express my thinking and my being. Yes, I have protested in the street, but that’s not my vocation. My vocation is visual. So, I want to use my vocation to express my thinking and express my point of view and my relationship to culture and my relationship to community.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

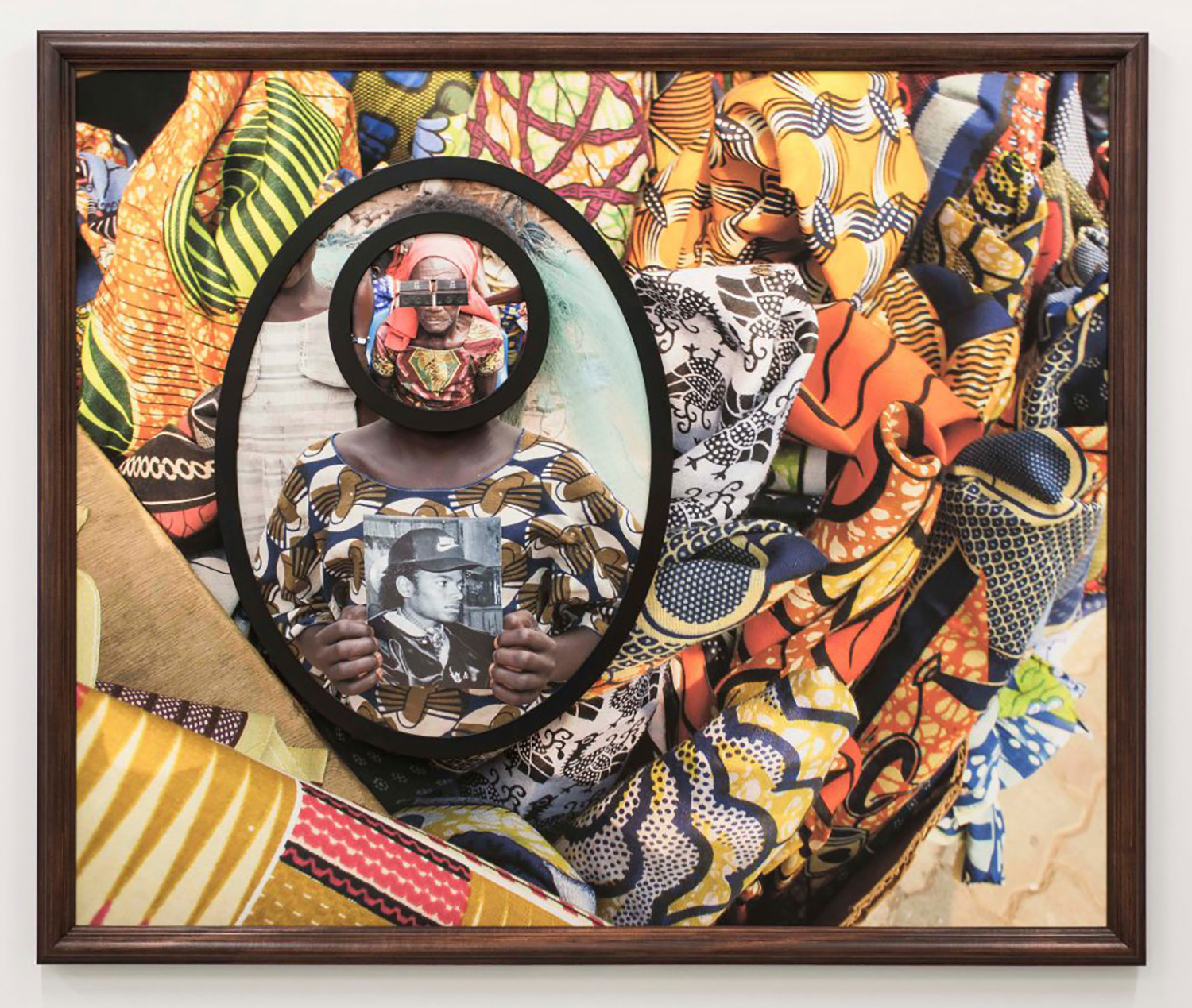

Diehl: Patterns (2), from 2018, is the only piece in your exhibition that incorporates a Michael Jackson photo, which is actually the only human face you show here. It feels different in so many ways from the other work, and it’s set off to the side.

Gray: That comes out of the series Exquisite Terribleness, which was where I dove into my MJ archive and intersected it with photos from my African archive. I wanted to see how that piece worked with the other works, and I set it aside. The drawing is a hallway. Since that Michael Jackson documentary came out [Leaving Neverland, 2019], the whole cultural relationship with MJ has changed, and I wanted to see how that affected that piece.

Diehl: There are several layered figures in that one—three, or four if you count Michael Jackson. They’re all covering each other up, so that his is the only face you see. It feels like a statement about portraiture. Like a way you can have a portrait without having a face.

Gray: Right. I did a show called Portraits (2018) at Meliksetian Briggs, and only a couple times you see a face. You can’t see the face, but you get a sense of the person, you get a sense of the narrative. In the Exquisite Terribleness series, I rarely showed Michael’s whole likeness. I didn’t want that read to hijack the whole work, because then it’s about celebrity. No, I want it to be about culture and Blackness and this representation of a Black person who is loved and hated, globally—the most famous Black person on the planet, if not the most famous person on the planet. He was a signifier that I wanted to wrestle away from Hollywood celebrity and entertainment and place him in an area where we can speak about the African diaspora. Because now you have to deal with history, you have to deal with slavery, you have to deal with economic exploitation; we have to talk India, East Asia, the Philippines, all of these colonial “destinations” exploited by Europe. He made himself a product. You know, the Faustian bargain. He went all in.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: So that’s why Michael Jackson, among the hundreds of celebrities that you have in your archive, is the only one that comes into the work. You wouldn’t say you’re interested in celebrity in general.

Gray: No. But, for me, commercial work and artwork were church and state. Now I’m really looking back and I’m saying, No, commerce is part of culture. One thing that John Baldessari taught me is context is everything. Context changes meaning. And so now, I’m trying to see the work that I did as a commercial photographer as part of mass media. I mean, pop culture pushes us forward more than high culture.

Diehl: Artists often feel self-conscious about not being part of pop culture, but they’re also really drawn to it, as another version of what they do.

Gray: As a Black man, ninety-five percent of my American clients in entertainment only allowed me to shoot Black celebrities. When I worked for Japanese clients, I could shoot anybody—Schwarzenegger, all sorts of people. But the Americans, no. I was limited to my race. That’s why when I came out of CalArts with my BFA, in 1979, my portfolio was landscapes, a subject matter that wouldn’t reveal my ethnicity.

I had a lot of inner conflict as an artist surviving as a commercial photographer. But entertainment—like a boxer, like sports, like gladiators—it showed us a way to get out of a certain kind of class and impoverished state. Options were limited. And then, as sustenance, we would actually listen to the blues, and hear that suffering and know it in a way others would not know it. Because it’s saying something very specific to us. There’s something encoded in it. When you hear the sigh, O! We know that. O! We’ve heard our grandmother come home and say that. So that’s why I’m relooking at my earlier Black celebrities.

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: Landscape is back in these collage works too. A more complex kind.

Gray: I’m owning it, and even saying, That’s Africa. I thought about that too, actually. Like, Oh shit, I’m still doing landscape. But it’s really visual culture. I went to CalArts at about the same time the Pictures Generation came out, but I’m not part of that. The person that put on Pictures along with Douglas Crimp, Helene Winer, was a curator here at Pomona. So I am very conscious that this place gave birth to the Pictures Generation, and I’m very conscious that although I’m from that period, I’m not in that.

Diehl: Right. There’s a lot made of the fact that you took the Michael Jackson photos you use. They’re not appropriated from pop culture. Maybe that’s the difference between you and Pictures. There’s more humanity in your approach to commercial images.

Gray: Absolutely. I’m charting out my history by reexamining the archive, because that’s where photos are fantastic: they freeze the historical moment. So I’m just replaying and remixing my history and putting it up there. I only appropriate—I use that word loosely—my own archive.

Todd Gray: Euclidean Gris Gris is on view at Pomona College Museum of Art, Claremont, California, through May 17, 2020.