Tom Sandberg’s Elusive Photographs Show Mysteries in Plain Sight

The Norwegian who pioneered photography in Scandinavia was always training his lens on the objects that we overlook, offering black-and-white scenes scorched of excess.

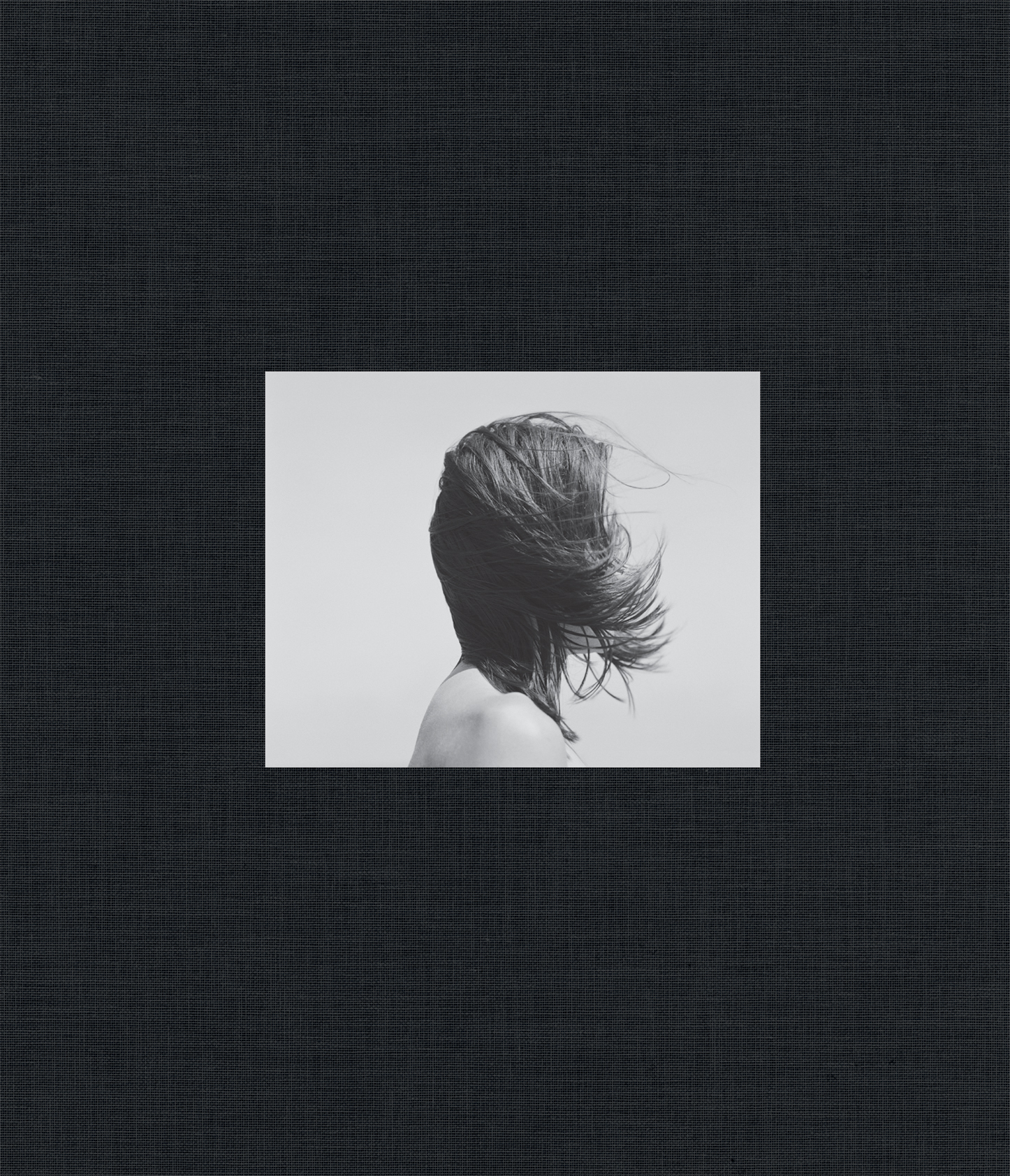

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 1985

In Japan, where I’ve made my home for thirty-three years, I often see people bowing to a telephone as they speak into the receiver. Ceremonies are held in temples every year for sewing needles that have given themselves up to make a kimono. My Japanese wife, while growing up in Kyoto, was taught to apologize to a table if she kicked it in a fit of six-year-old pique. Nothing, in short, is unworthy of the humbled reverence we call attention. Objects have lives, and the divisions we draw between animate and inanimate are a human-made creation; that’s one reason why the moon in Japan is offered the same honorific suffix as the emperor.

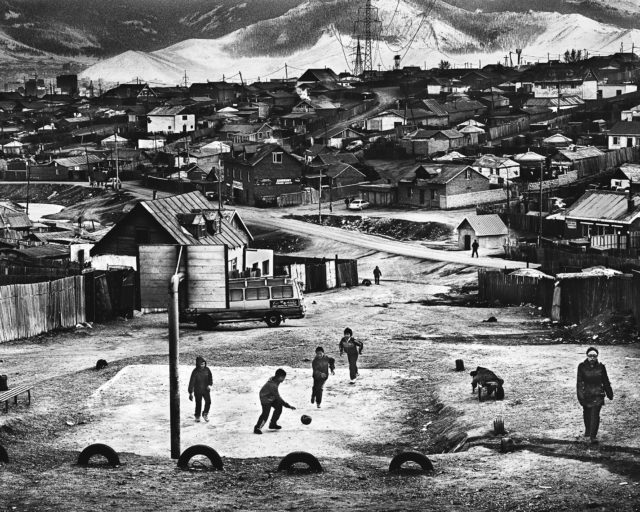

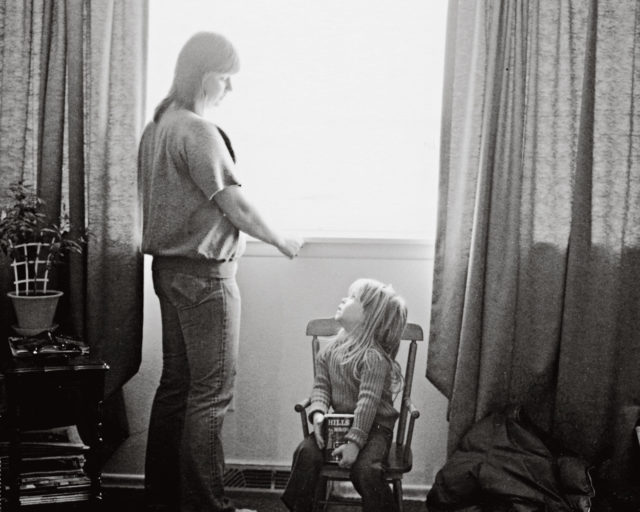

Much of that spirit comes back to me whenever I spend time with the work of Tom Sandberg. The Norwegian who pioneered photography in Scandinavia was always, it seems, training his lens on the objects that we overlook: Not the people enjoying lunch, but the paper bag beside them, so vivid we can almost hear it crinkle. Not a jet cutting through the heavens, but the emptiness that surrounds it. There are vehicles—cars, planes, and buses—in much of his work, and yet the images are about movement of a subtler kind: misty and precise as smoke rising from a stick of incense, they focus not on the cars outside but on the way a wind stirs a filmy curtain and, maybe in so doing, stirs us.

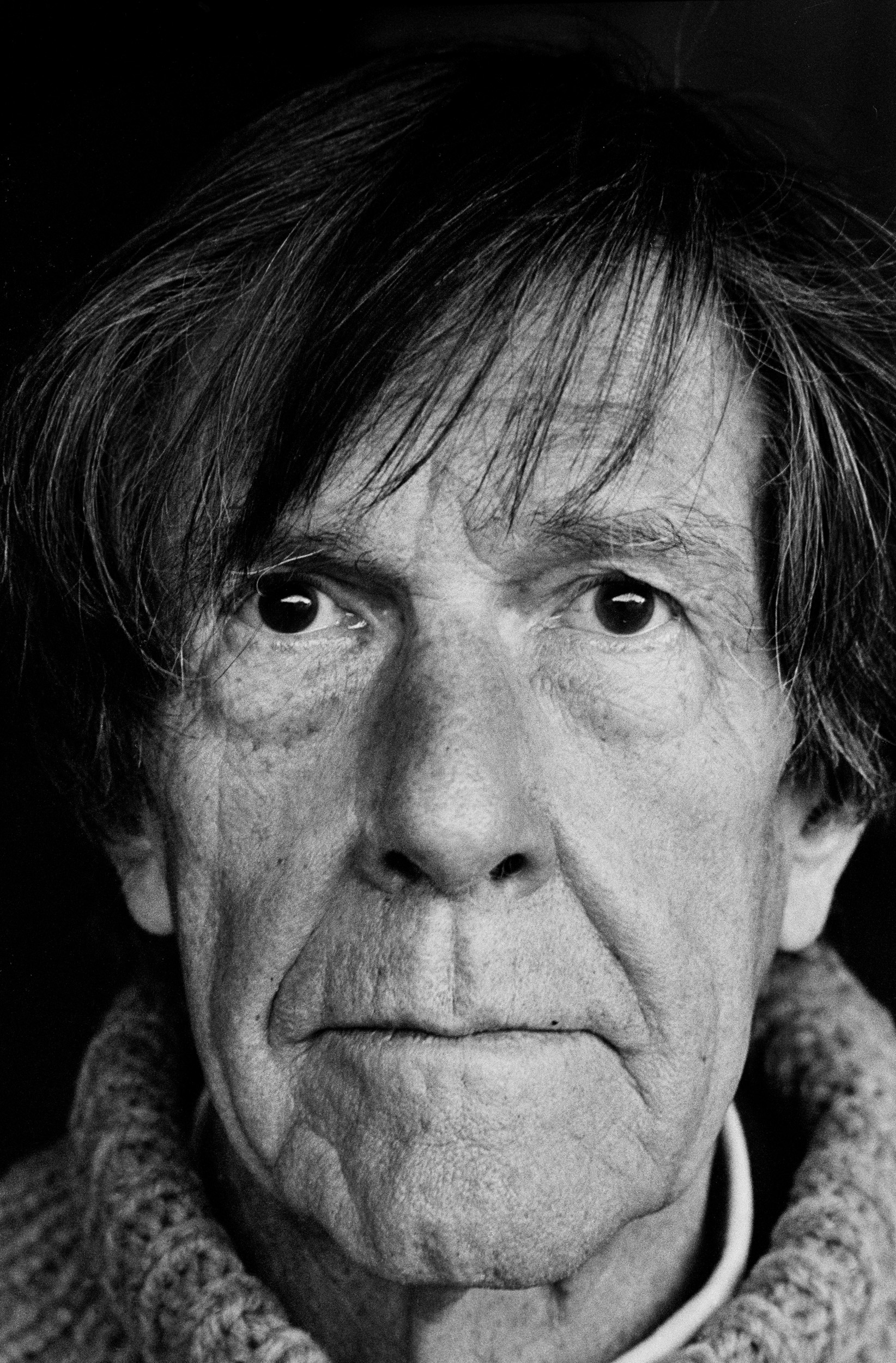

This mix of specificity and absence is deepened by the fact that, though he was granted the honor of a solo show at New York’s MoMA PS1 in 2007, Sandberg liked to call his younger self a “small gangster from Norway.” In video interviews, I see a grizzled, watchful figure, contained and serene in the snow as he waits to find images with his predigital Pentax.

He organized happenings on the Oslo music scene and, in his youth, chose to sustain himself on donations of food from friends who worked in restaurants. In the early 1970s, he earned money as an assistant dogcatcher and loading frozen pig carcasses onto trucks. At that same time—photography not being regarded as much of an art in Norway—he began studying the craft at Trent Polytechnic in England, where he encountered an old master who produced large-scale black-and-white analog evocations of light, Minor White.

Much like his mentor, Sandberg grew fluent in the art of suggestion. His pieces are mostly untitled. They sit calmly in the midst of all they do not disclose. Thus, very often, they take us beyond the eye to somewhere deeper inside. I don’t know what to make of the reflections of all those faces in a bus, and when I look at his clouds swirling against blackness, smoke gets in my eyes. As with classic pen-and-ink drawings, these images invite us to complete the picture ourselves—or perhaps they simply ask us to live uncomplainingly with what we cannot hope to fathom. Everywhere in the world we take for granted, Sandberg might be pointing out, are enigmas as open as that paper bag. “I photograph just about everything,” he told the BBC in 2006. He even took his camera with him when he went shopping.

Photography, he also said, is “a complex dialogue between shades of gray.” He labored long and hard, or more than forty years, to find a thousand shades of “gray and matte,” working with the same type of film and developer throughout. In the process, he often gave us a universe in which there seems to be no color at all.

Or, phrased more precisely, he appeared to be listening, with all his being, to a universe that at moments offers us the silent treatment and at other moments speaks in whispers, in spectral trails of smoke, or murmurs through faces barely discernible in the rain. Some of his blacks are so inky they seem as if they were shouts—“Keep out!” Elsewhere, we lose all orientation in fields of silver and a whiter shade of pale.

Sandberg offers us attention so scorched of excess—and of explanation—that it comes to us as a secular prayer.

This dogged, undeviating artist—the son of a photojournalist—might, in fact, be trying to release us not just from the simplicities of black and white but from the black-and-white way in which we too readily strive to tame the universe. His work is about emotion, but the kind that cannot be pushed into any pigeonhole (or reduced to words). Sandberg was the first photographer to buy a house in the artists’ colony set up on Edvard Munch’s old estate outside Oslo. When he bought his first medium-format camera, he told a visitor there, “I started dreaming in six-by-seven.” That same visitor described the studio as “a white forest of rolls of large prints from the Picto lab in Paris.”

There’s something of an alien’s gaze in much of the work; this is how a brother from another planet might apprehend a hand, a child’s pigtails, a pair of sunglasses. When we do see figures in a landscape, they’re nearly always alone, small, against a backdrop of machines and high buildings: a classic vision of alienation. You don’t have to observe Sandberg’s work for long before noticing how still lifes, through his eye, are gnarly with texture and rhyming patterns. Yet the human body—in his nudes or portraits of babies—comes to seem just a shape, a cluster of tubes. Naked bodies are the opposite of erotic here.

What all this means is that he moves us to respond to photographs differently from how we usually might, which is why I write of listening as much as seeing: when I look at his airplane on an icy day, I can feel the slippery ground under my feet and the hard flakes of snow in my face more than I can make out anything visually. With his persistent images of clouds and smoke, it is the same: they’re not something just to be seen but rather to be reflected on. Sandberg can find what looks to be a giant lizard in the harsh terrain of a mountainside; he can give us pure canvases of light akin to a Mark Rothko work or a James Turrell Skyspace. In one of my favorite images here, we get not just the heavenly geometry of an illuminated tunnel, but a question: how much is this Nature’s work, and how much humans’?

There’s something close to religious about this ghostly work, even though the clouds he presents are seldom celestial or shot through with heavenly rays. At heart, he’s giving us not just the world but all that cannot be shown and can never be seen. We hover between the earthly and something else. In that regard, it is surely no surprise that one of his great portraits is of a haunted, visionary John Cage, the man who wrote the book on silence and reminded us, in works such as 4’33”, that what the artist offers us is not the whole picture; his collaborator is circumstance.

Cage was a great believer in randomness and in the way that everything around us can, if seen or heard in the right way, be taken as a work of art. We don’t need to rely on simple distinctions between what is interesting or beautiful or important and what is not. It is the eye—of audience as much as artist—that makes a picture and, in so doing, makes the world.

All photographs from Tom Sandberg: Photographs (Aperture, 2022). Courtesy Tom Sandberg Foundation

Of another caretaker of mysteries, Cage once told an interviewer, “As the words become shorter, Thoreau’s own experiences become more and more transparent. They are no longer his experiences. It is experience. And his work improves to the extent that he disappears. He no longer speaks, he no longer writes; he lets things speak and write as they are.” That chimes beautifully with what I find in Sandberg’s disappearances. Nothing comes between us and what we’re seeing. We’re getting reality—or mystery—unmediated. Or so, at least, he makes me feel.

The more I look at Sandberg’s work, in fact, the more I find myself disappearing, too, into the resistant images he shares with us, lost amid those cityscapes where humans seem tiny to the point of insignificance. And the longer I inhabit his eerily alive abstracts, the more I come back to some of Cage’s meticulously inexplicit koans: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it.” And “Is there such a thing as silence?”

“Beauty is now underfoot,” Cage also wrote, of his friend Robert Rauschenberg, “wherever we take the trouble to look.” That could be the perfect epigraph for this book. Sandberg himself once quoted Rauschenberg: “I don’t know where I’m going, but I know I’ll get there on time.” Some of Sandberg’s images are so distinct, we can’t look away from them; others are so elusive, we look and look and still don’t know what we’re seeing. In all his work, Sandberg, who died at sixty, fourteen years into the new millennium, offers us attention so scorched of excess—and of explanation—that it comes to us as a secular prayer.

This essay originally appeared in Tom Sandberg: Photographs (Aperture, 2022).