Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory, 2023

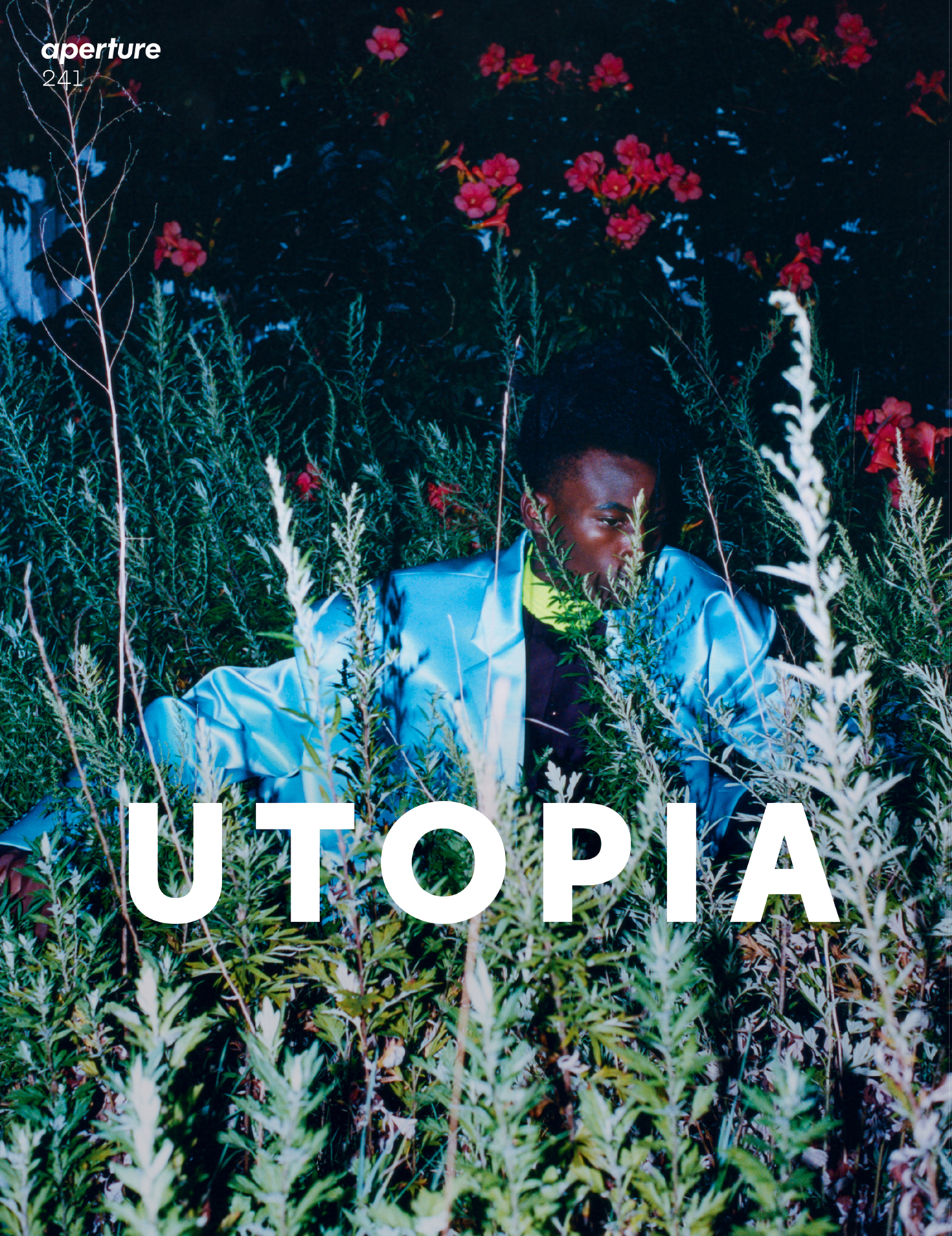

The SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia, is a former depot building of the Central of Georgia Railway, a line that once transported cotton and drove the state’s economy in the nineteenth century. One of the museum’s galleries, at nearly three hundred feet long, retains the heritage of the building, constructed in 1853, with its archways and original Savannah-gray brick. This is the setting for Tyler Mitchell’s latest exhibition, Domestic Imaginaries, which marks the debut of new fabric prints by the photographer and sculptural pieces inspired by vintage furniture. “I started imagining the cargo that came through here, the people that came through here, that maybe worked here, what this exact site was hundreds of years ago,” Mitchell, who grew up in Atlanta, told me, when the exhibition opened in September. The light-filled gallery’s unconventional shape presented an opportunity for him to move photographs off the wall, to play with the idea of the home and the backyard as an art space, and to pursue a form of storytelling based on gesture and memory—a “collective memory,” Mitchell says, “of what nature and the South and the Southern landscape means for Black people now and then.”

At the center of Domestic Imaginaries, a laundry line zigzags from a brick wall to a row of tall windows. Numerous photographs, dye-sublimation prints on silk, jersey, linen, or cotton and clipped with clothespins, sway gently as visitors move about. The pictures retain the signature pastel color palette of Mitchell’s well-known fashion and editorial work, but the figures are elusive: many are only partially visible, obscured by sheets of fabric within the original image, which offers a surreal, mise en abyme quality. “I wanted to push further into loosening the boundaries of photographic presentation,” Mitchell says. “It’s not just about pushing against what a photograph can do, it’s also expanding into what stories a photograph can tell through gesture, through poetic shape.” Other fabric-based photographs are draped over open frames and installed on the wall, an homage to David Hammons’s mixed-media paintings that stage a refusal by blocking visual elements, thereby inciting all the more intrigue.

Domestic Imaginaries also contains several works, commissioned by the SCAD Museum of Art, fabricated in Georgia cherry and walnut, and modeled after objects Mitchell found in antique shops or through his research about midcentury Black domestic life. Some of these “altars” contain books of literature, sociology, poetry, and photography by artists including William Eggleston and Baldwin Lee. The spines or covers are visible through glass windows, in the way that precious heirlooms might be displayed in a home, while some panes are covered by Mitchell’s own photographs, printed on glass. One altar, a hexagonal tower, seems to ask the viewer to move continuously round and round, absorbing all the words and references at new vantage points. And as the seasons change, the arc of the sun will cast varying degrees of light throughout the exhibition, making each encounter a new one. In the conversation that follows, Mitchell speaks about these themes with Daniel S. Palmer, chief curator at the SCAD Museum of Art, and how Domestic Imaginaries is an exhibition that should be experienced “holistically.” —Brendan Embser

Daniel S. Palmer: Domestic Imaginaries is your most ambitious exhibition to date and your first solo exhibition in your home state. Maybe we should start off talking a bit about your upbringing—and the influence of Georgia on your artistic outlook?

Tyler Mitchell: My work has been informed by narratives of how Black life connects to nature and to the outdoors. This exhibition heightens that to a new degree, I would say. Being from suburban Atlanta, I reflect a lot on the sheer amount of nature that surrounded me in my upbringing. Atlanta has the most amount of nature in any American city. I like the idea of making images that offer an expanded lens of where Black life can reside. I don’t think that we immediately, in terms of the wider culture of images of Black people, think of Black life as being tied to nature in a deeply leisurely way. I think we’re constantly bombarded with other kinds of images. So, my work tries to center that as a place for meditative repose and leisure, as well as joy.

Domestic Imaginaries frames these ideas as an installation and invites the viewer to go on a journey through proverbial domestic space, from the outdoors, which is signified by laundry lines—the photographs hung on diaphanous fabrics in the gallery—to the altar sculptures, which reference historical furniture and place. I situate my own photography inside the sculptures.

Palmer: That leads perfectly to a discussion about the gallery within the museum where your work is exhibited, which we call the Pamela Elaine Poetter Gallery. It is a unique and large-scale space that is about three hundred feet long. One side is all windows out to the museum’s courtyard, and the other side is a wall of historic Savannah-gray brick. It’s a very impressive space but also a challenging space for a lot of artists. I think you approached it so brilliantly. What did you think about the space when you first came to the SCAD Museum of Art to consider doing a show?

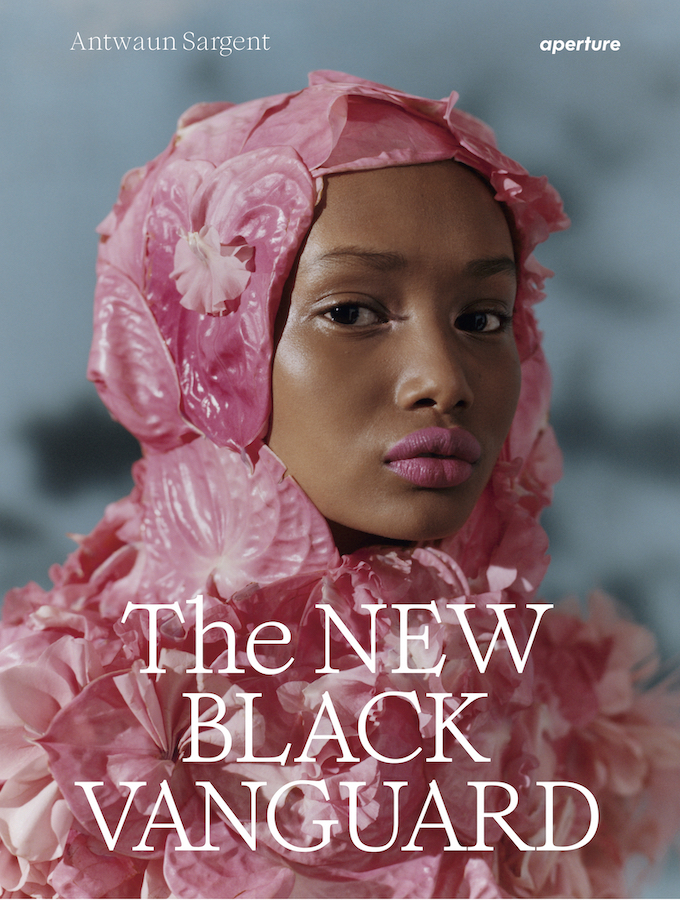

Mitchell: I visited SCAD a little over a year and a half ago, initially for an “in conversation” with Antwaun Sargent. And then I saw the museum, and I was very impressed with the spaces. The Poetter Gallery is the only daylit space in the museum. When you told me that the museum is situated in what was the oldest train station in Savannah, Georgia, and in that gallery you could see the arches of the Savannah-gray brick, where the train would pull up and where cargo was moved, immediately there was this flood of historical imagery that came into my mind. It became a space I was inspired by physically but also historically. And the idea of situating my work against that backdrop created for a really powerful conversation. You think about the idea that the bricks were themselves laid by formerly enslaved people, that Savannah is a city that is still alive with its complicated and sometimes horrible history—all of that plays a role in this work. In many different ways, my work is about striving for self-determination, for agency, for empowerment and joy against the backdrop of history.

Palmer: Then the question of what we would do in this space arose. You approached that by making your most ambitious laundry-line work to date. How did the laundry line as a series begin? And how did it evolve for this installation?

Mitchell: The initial idea started over three years ago, when I was invited to do an exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York, which was curated by Isolde Brielmaier. There was a very unique space that I was given, which was a long and very narrow hallway, about sixty feet long. It suddenly felt inappropriate to hang framed works in that hallway. The viewer might breeze past them or might not be able to properly engage with them at different distances. It was actually an idea borne out of a need, a very functional need for what was going to happen in that space. I’ve always been interested in playing with ideas of photographic presentation in a gallery space, but it was there that I thought to make my first laundry-line installation. It included six years of my portraits across both commissioned and personal work.

This iteration, expanded for Domestic Imaginaries, is a marriage of form and content. These new images in the laundry line think more deeply about textile and fabric not just as a presentation or aesthetic choice, but as a formal and conceptual choice. I’m thinking about how textile contains cultural and material significance. I’m thinking about how fabric plays a role within the home, how it can contain memory, physically and literally, by being worn, by being engaged with as lives, as sheets, as towels—how those things play a functional role in our everyday lives. In the images themselves there are figures silhouetted or masked or partially hidden by fabrics blowing in the wind. Fabric is literally in motion and interacting with the young Black men and women that I photographed.

Palmer: Since the gallery space can be navigated in two directions—there is not a formal front or back—the exhibition has created an environment for people to navigate and explore. Then your images have this trompe l’oeil dimension to them, where you see a picture of somebody behind fabric as well as laundry lines and clothespins in the image, but you also see the physical laundry lines and clothespins that are actually hanging the work in the gallery. Can you share a bit about the kinds of scenes you were setting—and how you chose the different types of fabric that certain images were printed and displayed on?

Mitchell: It was a very intuitive process. I’m interested in wanting to disrupt the formality of the framed photograph. I’m interested in making dynamic experiences with my work, which comes about through sculpture and installation. And that while I’m committed to the photographic image as an object, I’m also committed to expanding on notions of what that can be. The photographs themselves continue a lot of the scene-making that I do in my other work, my portrait work, which features young Black men and women, who I usually cast, whether they’re young artists, whether they’re friends of friends, whether they are models that have appeared in fashion projects that I’ve done before. They are the “protagonists,” as I call them. We have a day together, in which we make these images, in which real moments of leisure are experienced, real moments of community are experienced, and real moments of togetherness are had. Usually, when I’m making my work, I allow for a looseness and collaboration with my sitters. In one image you see two young men silhouetted lifting up or unveiling or revealing or concealing themselves behind fabric. You see a young girl posing in front of a fabric that’s blowing up against her back in the wind. And you almost feel the wind or that joy yourself as the viewer. And that’s the goal of the work.

Palmer: The other central aspect of this exhibition is the series of altar works that you made—the sculptural pieces that reference historic furniture and evoke domestic spaces. This feels like another point of connection. How did these altar works come about for you? Why did you think it was an important element to incorporate?

Mitchell: Throughout the past few years, I’ve been thinking about the essential power in how we dress everyday spaces like our homes. The gesture of framing and displaying a photograph of a loved one can be a very simple or ordinary act, but one that shows true and high admiration. The home is the most important public-private gallery in the world. It’s where you invite those close to you, or guests, to come and see how you live, and oftentimes at the center of that is photography.

In 2019 I was named a Gordon Parks Foundation Fellow, which culminated in a solo exhibition at the Foundation’s gallery space in upstate New York in 2021. At that point in time, I don’t think I had been home to Atlanta in over eighteen months due to the various COVID-19 lockdowns, and having been distanced from my roots for so long, only then was I starting to think about making work that really considered how those years were formative to me. So I made, first, a work that’s called The Grand Sofa, which is a custom-fabricated sofa which features my photographs of a Haitian family in New York embedded into the upholstery. I started to think about these domestic objects as containing within themselves very important visual memories and moments. That’s where these altar sculptures emerged from. And they also fused my own love and compulsive obsession with collecting photobooks. Some of the works include books from my own personal library and studio—Roy DeCarava’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life; Robin Coste Lewis’s To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness; and even Blu-ray DVDs like To Sleep with Anger, directed by Charles Burnett. Those books and DVDs are repositories of knowledge, and they come together to string a sentence about the makeup of my own artistic practice, and about image-makers, writers, and thinkers that have come before me that I would like to keep with me.

Palmer: You’ve also embedded images in these altar works. Your own images that you’ve taken and printed on metal or glass, but you’ve also included smaller, postcard-like reference images. Between those tipped-in images, the books, and the DVDs, I feel like this is a wonderful annotation of all your artistic inspiration.

Mitchell: Exactly.

Palmer: To many people, you’re known as a commercial photographer whose images grace the covers of magazines or fashion photography spreads. But, I think that this exhibition is so important in showing that you are an art photographer too. Not just an art photographer, but also a major innovator in the field of fine art, that you are pushing photography beyond the bounds of the printed, framed photograph. The final element in the show is the group of three “relief” works which each have a walnut frame mounted on the wall with an image printed on fabric draped over them. This really feels to me like a thesis in innovation in photography.

Mitchell: That’s a very high compliment. And I can only hope to continue to push in all those ways. I like to think of myself as someone who is pushing the boundaries of categorization in general, be it fashion or art. I’m thankful to have done that with this exhibition. It has been such a beautiful journey to find a community initially as solely a fashion photographer, to find, I would say, a purpose. I enjoy communicating visually about personhood by way of style and by way of clothing. And I was also a student under the tutelage of Deborah Willis, taking classes like Black Body and the Lens at NYU, where I found a way to marry my own concerns, questions, explorations about identity—my own identity and the identity of other young Black people around me, my contemporaries—into this work.

All images courtesy the artist, SCAD, and Jack Shainman Gallery

Palmer: Domestic Imaginaries is on view here at SCAD, at a teaching museum. I wonder if we could wrap by asking if you have any advice for the students here at the university, and young artists generally. What do you hope to impart with this exhibition?

Mitchell: One element that I really enjoy talking about with this exhibition, and what I hope could potentially inspire others, is the emphasis of humanism in the work. The word humanism has been thrown around quite a lot in wider discourse, but to me it’s really a certain striving for moments of personal and unencumbered joy or happiness and whatever that may look like, especially, I have to say, in these anxiety-ridden times. Hopefully the work encourages young people in general, but especially young artists, to make work that is about their own interiority, and their own visualizations of joy.

Tyler Mitchell: Domestic Imaginaries is on view at the SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, through December 31, 2023.