From an Italian Photographer, the Bygone Days of Bohemian New York

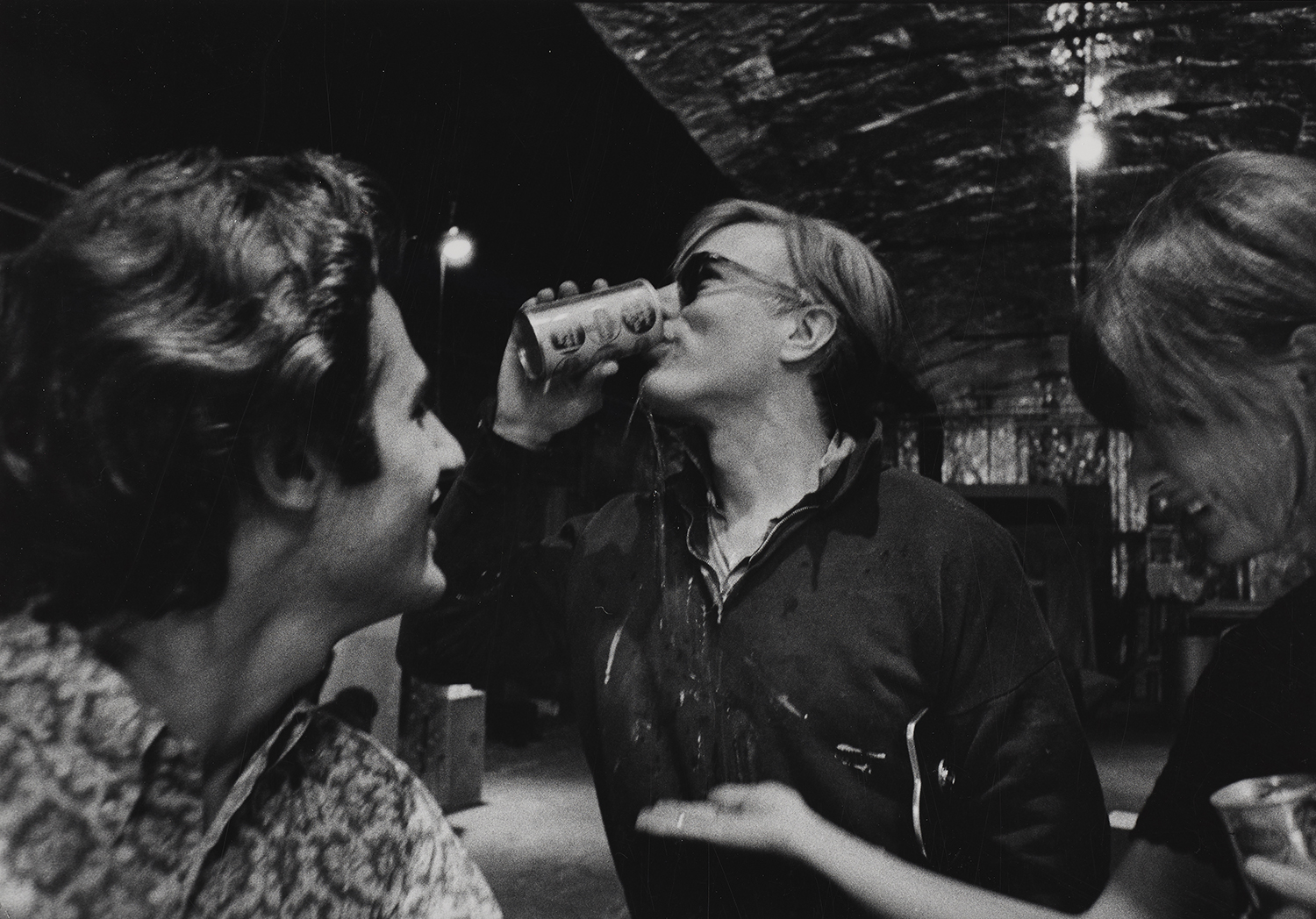

Ugo Mulas, Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick, 1964

It often takes an immigrant to show America to itself. Italian photographer Ugo Mulas only visited here, but his view of New York in the mid-1960s changed the way we see the city and the bohemian enclave it stands for. That world—with its sizable lofts, oversize ambition, and stance that life could be art and vice versa—only barely exists today (if at all) in neighborhoods like Chelsea, where more than one hundred of Mulas’s images hang at Matthew Marks Gallery in Ugo Mulas: New York–The New Art Scene, a thoughtful exhibition organized by curator Hendel Teicher.

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Born outside of Milan in 1928, Mulas thought he’d become a lawyer, but he abandoned school after falling in love with Milanese nightlife, photographing people posed at the infamous Bar Giamaica with a borrowed camera. By 1954, he was the Venice Biennale’s official photographer; ten years later, he’d developed a style: inquisitively formal, full-frontal, and based on long nights watching theater rehearsals. He made definitive portraits of Alexander Calder, David Smith, and Lucio Fontana. And he formed crucial friendships with figures like Leo Castelli and Alan Solomon, whom he met at the 1964 Biennale and who convinced him to take a trip to New York.

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

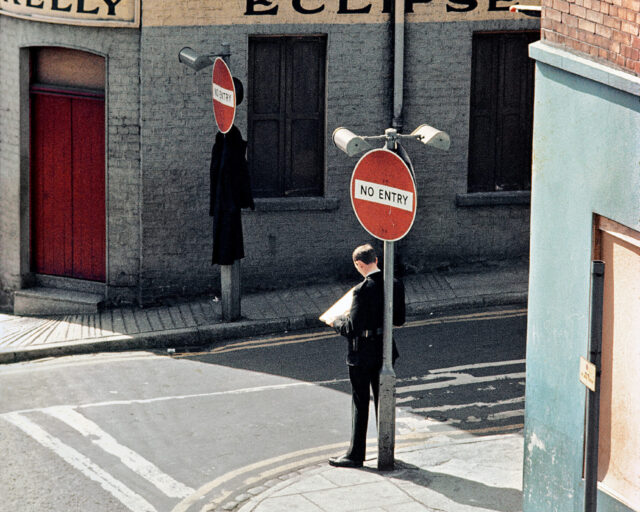

“He didn’t speak much English,” Teicher told me, “but you don’t have to speak much English as a photographer.” Instead, Mulas sat in artists’ lofts, around dinner tables, and in studio rehearsals, galleries, and clubs. “I feel impersonalized,” Mulas once remarked. “Thus I try to understand what is happening around me, doing it through my photos.” He returned in 1964 and 1967, and produced an epochal catalogue of what he saw, 1967’s New York: The New Art Scene. Teicher pulls from this book and unpublished work from the time for her show, which greets viewers with fascinating maquettes of the manuscript, before opening into zones for Mulas’s studies and collaborations with a who’s who of New York’s midcentury artistic characters.

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

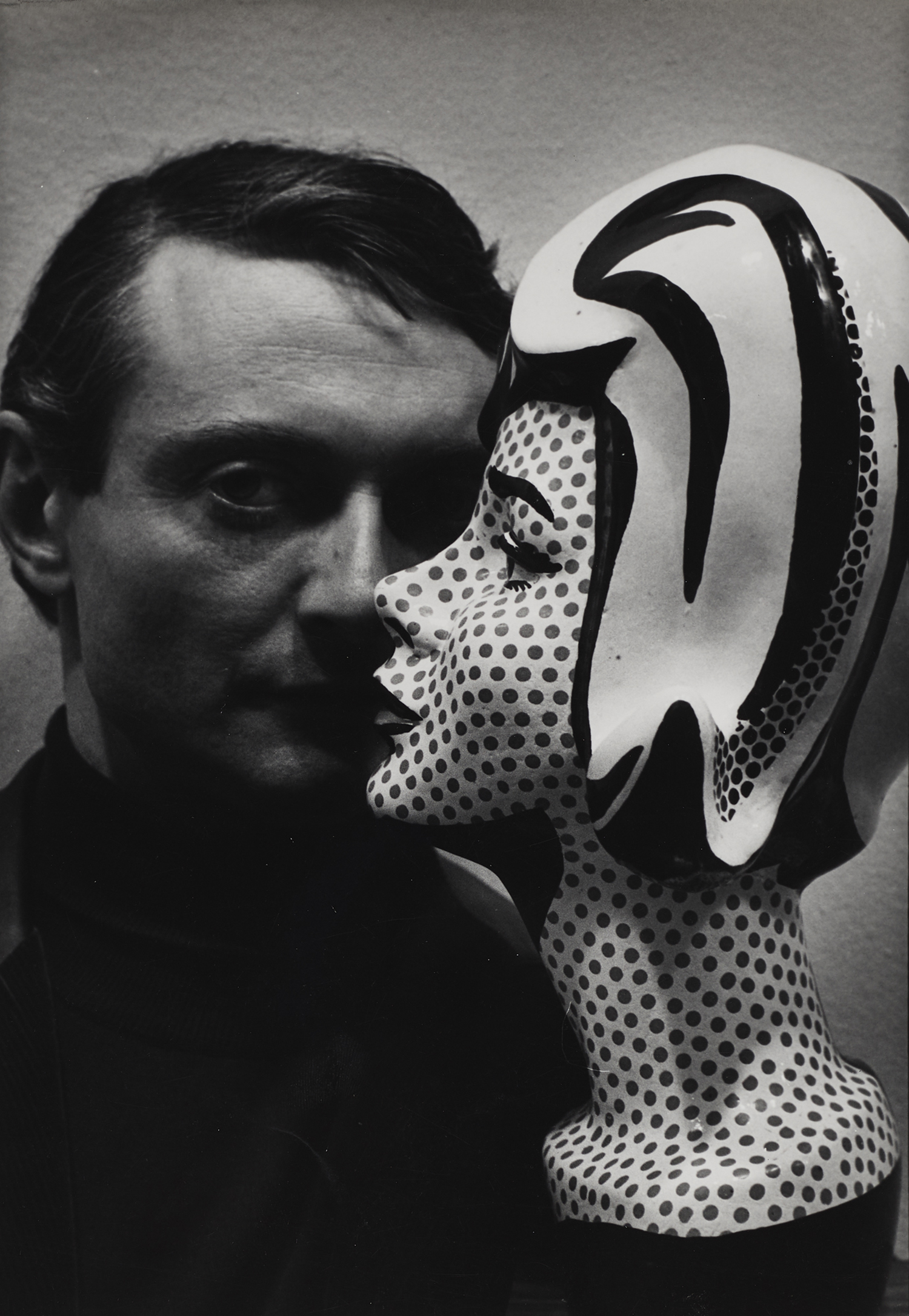

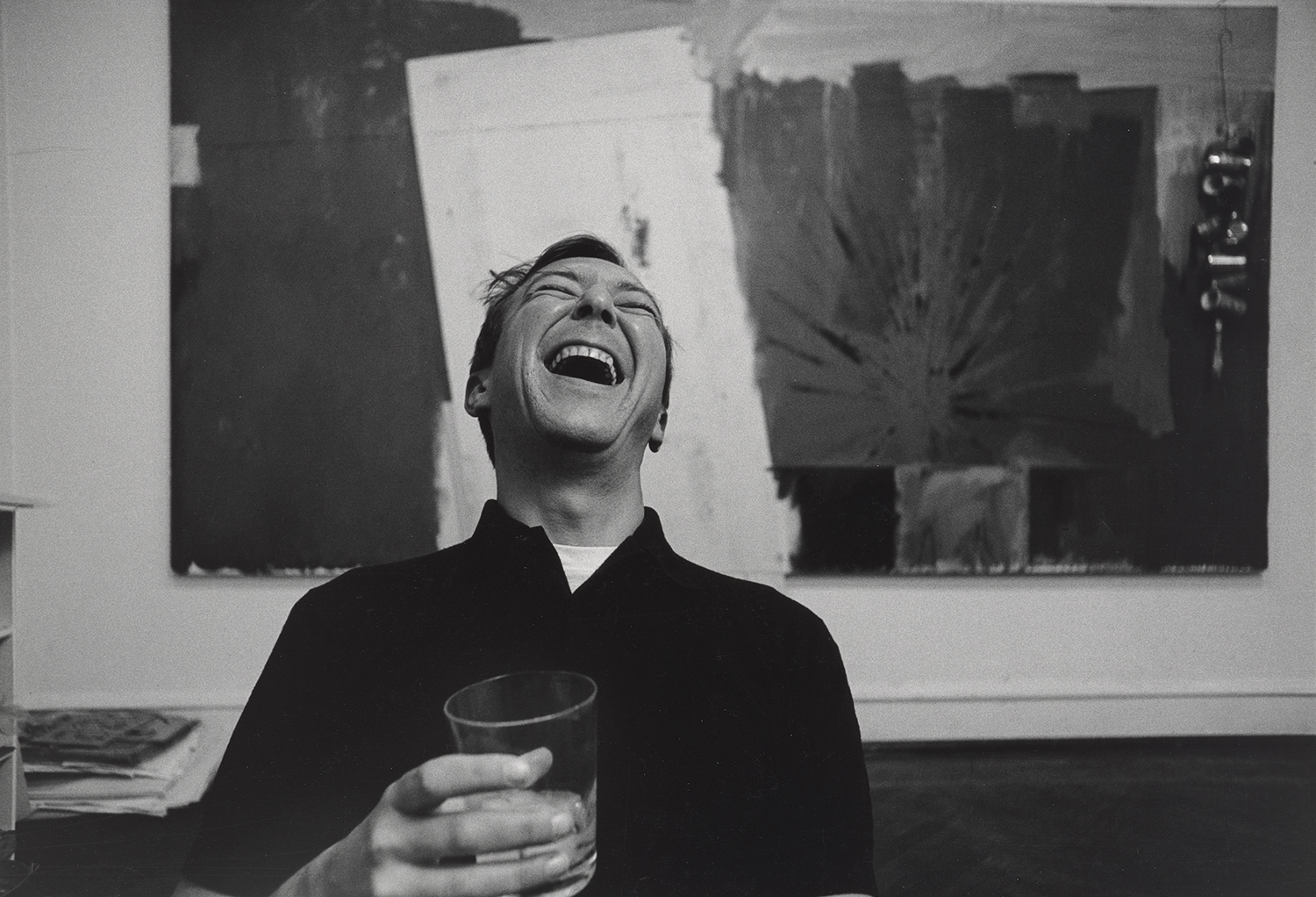

Each zone centers one of Mulas’s formal innovations: printing an entire roll of film as a single image, thus transforming time spent watching an artist work into a flip-book, or a skyscraper with parties or workspaces glimpsed through rows of windows, or even from a distance, a kind of Mondrian grid. Favored images earn pride of place next to contact-sheets-as-photographs: Marcel Duchamp, Mulas’s first artistic love, standing between drapes like a magician appearing; Barnett Newman, standing stiffly in a suit and pointing to a vast, empty canvas as if to say, “that’s enough.” A series of action shots of Roy Lichtenstein integrates fascinating photographs of comic book scraps taped to the walls with glamor shots of the artist pressing his face to dotted busts and other merchandise, a self-conscious blurring of the lines between product and producer. Mulas’s portraits of Andy Warhol manage to find something new in someone overexposed even then, with a 1964 photograph drawing attention to the fragile veins in his hands, those physical tools Warhol worked so hard to make irrelevant.

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

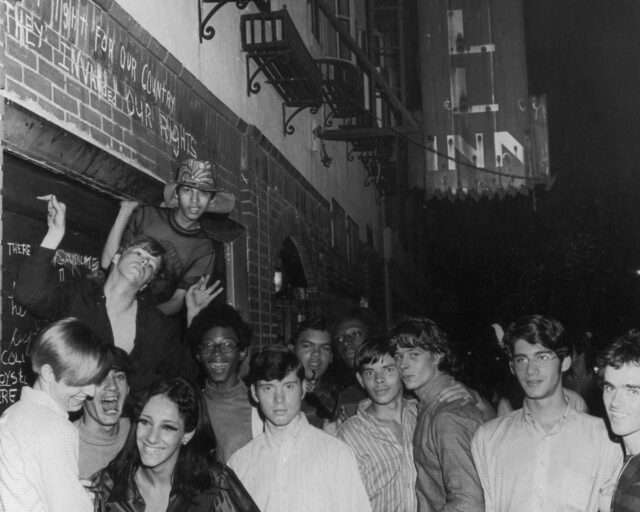

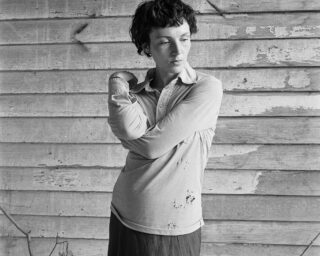

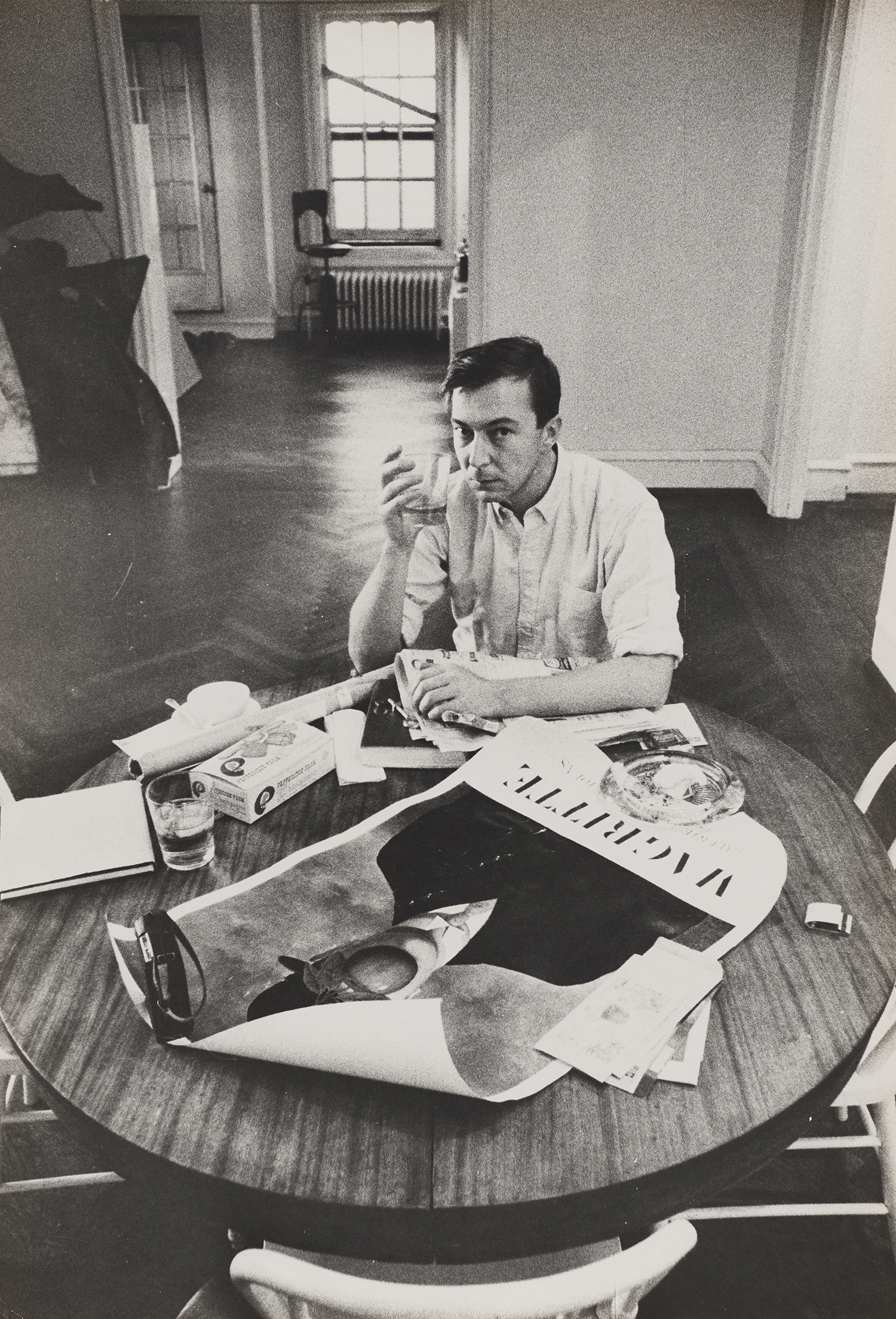

“Mulas always gives you enough information to understand what kind of character you are dealing with,” Teicher says. And what characters! Juxtaposing photographs of Warhol’s world—a police raid on the Factory with a man thrusting his ass out beside another man pounding a bottle of beer—with those of Robert Rauschenberg’s tells you everything you need to know about the difference between the two artists. Rauschenberg’s vast loft includes domestic clutter and a long table of friends invited for Thanksgiving dinner; other photos study Trisha Brown arranging her body in practice, or Rauschenberg half-naked in shadows, mid-thought and yet in costume (for Spring Training). In these images, life and work are as carefully balanced as Mulas’s compositions.

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Watching Jasper Johns changed Mulas’s idea of what should be shown. In as intimate a moment as is possible between two artists, Mulas captured Johns from behind in the act of creation. The power dynamic—one artist transforming the labor of another into work of his own—unnerved him. “If the painter agrees to be shot, the photo is purely for public relations purposes,” Mulas later explained. “If the painter refuses and I succeed in convincing him, the photograph is an act of violence.” Mulas rarely photographed artists at work again; his portraits of Johns instead show Johns wrapped in sweaters and staring down his gaze, or pressing a sweating face into the canvas as if it were a pillow or a lover.

© Ugo Mulas Heirs and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Mulas left New York and returned to documenting the Italian art world; an accomplished writer and critic, he finished the series Verifications, a kind of meta-manifesto, shortly before he died of cancer in 1973. The images in The New Art Scene now look like arguments for—more so than evidence of—a world that takes artistic practice seriously. One hopes someone new is able to come to New York today and not only make this argument, but win it. But it’s surely more difficult now than it was for Mulas. “One needs to realize that my point of view is not only optical, but mental above all,” he once said. Which is to say that maybe this world was a state of mind after all.

Ugo Mulas: New York–The New Art Scene is on view at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, through August 16, 2019.