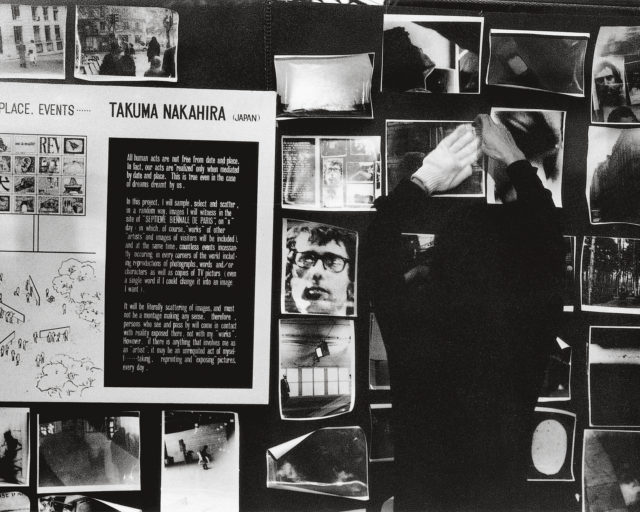

Quentin Bajac at the Museum of Modern Art, August 2013

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

Last January Quentin Bajac, a native Parisian, became chief curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. Given the authority of that position, MoMA invested a great deal of intellectual currency in the appointment. Bajac had been a curator of photography at the Centre Pompidou since 2003, and its chief curator of photography for the past six years. Before that he spent eight years as curator of photography at the Musée d’Orsay. Among his publications are a three-volume survey of the history of photography, and guides to both the photography collections at the Pompidou and the Musée d’Orsay. He holds the Chair in the History of Photography at École du Louvre.

As photography becomes an ever more vital art-world presence—the number of exhibitions, publications, and art fairs devoted exclusively to the medium continue to grow—it has also been undergoing something of an identity crisis. Can it remain its own medium or should it be absorbed into the larger multimedia universe that modern museums are now contemplating? How does Bajac’s curatorial philosophy embrace competing ideas about where photography falls in relation to the art world? Should he set the tone for the field, as his predecessors have in the past? How will MoMA shape the ongoing narrative of photography? These are some of the questions I raised during our conversation in his office in MoMA’s photography department last June.

Philip Gefter: Your seat at the Museum of Modern Art has a storied legacy. Given the four people who preceded you—Beaumont Newhall, Edward Steichen, John Szarkowski, and Peter Galassi—do you find it intimidating? Challenging?

Quentin Bajac: A little of both, perhaps. You’re referring to what has been called the “judgment seat of photography,” to cite Christopher Phillips’s essay, written in the 1980s, about MoMA’s role in photography. But that was thirty years ago. Today, MoMA is only one of the judgment seats. Now there are other major institutions involved in photography. I think MoMA still has a kind of specificity because of its long and deep commitment to photography. We’re writing one history of photography at MoMA, while other people or institutions are writing simultaneous histories.

PG: Do you think the history of photography as it was written in the twentieth century was American-centric, or even New York–centric? And, if so, has that changed?

QB: Yes, it’s true, and it has changed a lot. I would say that from the 1930s on Americans tended to think of photography as an American medium. A bit like jazz—that was the American art. And yet it’s also true that if you look at the history of photography at MoMA, Steichen was open to European photographers, and Beaumont Newhall, too, spent a lot of time in Europe. John Szarkowski was, of course, a wonderful curator and one to whom I think every historian is indebted. But he was, as you know, very American-focused. If you a look at the exhibitions he organized during his thirty-year tenure at the museum, you have a repetition among historical figures that sometimes included non-American photographers—Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, Lartigue, Atget. He exhibited Japanese photographers. But you could probably count them on the fingers of one hand. As soon as you turn to contemporary photography, that is, photographers of his generation at that time, they are all American.

PG: MoMA conducted an international search for over a year before filling your position. What do you think it was about your background and your understanding of photography that convinced the museum that, of all the candidates, you were the one to fill such large shoes?

QB: Probably the fact that I was not American. I think that was important. Maybe they had the feeling that photography was becoming more and more global and someone who is not American, who is not linked or connected to that long history of photography, is more appropriate now. Of course, this was my first question to them when they called to ask me if I would consider the position. I do not have a PhD. I am not a specialist of American photography. I did not think they would even consider a non-American curator. But perhaps they wanted to amend that history.

PG: Which of your shows at the Pompidou would you say was of particular significance to MoMA?

QB: The big show we did about Surrealism was important, because it dealt with photography and film. I think the fact that I have always worked with photography in connection with other mediums was significant. The Pompidou has a long tradition of cross-department, multi-disciplinary shows. Also, at the Musée d’Orsay, I did a lot of shows on the relationship between photography and other media—film, painting, and sculpture. I think that was important for MoMA as they are trying to generate greater dialogue between the departments and disciplines.

PG: The museum’s interest in the cross-pollination of media makes sense, particularly given the current moment in the art world, when multiple media are being utilized on various platforms simultaneously. Obviously the contemporary art museum has to contend with this evolution. But I wonder how photography fares in all of this. Photography spent the past forty years in an uphill battle to prove itself a viable art form among the other disciplines. Does the museum want to take away its autonomy?

QB: Of course photography has established itself as an art form over the past thirty or forty years—the battle is fought and won. Photography can be quite confident about its strength and confront other techniques without trying to define its identity.

PG: The criteria for assessing a work of art—whether a photograph in the documentary tradition or a constructed image—has had to change due to new practices and platforms, including the Internet and social media, that have emerged over the past twelve or so years. Has your criteria changed? For one thing, how do you isolate the artist from the practice?

QB: Practices have changed. The real problem facing curators and historians of photography is the overflow of images. The main concern for curators in the 1960s, ’70s, and even early ’80s was to provide access to photographic images. Now we have too much access to too many images. So we need to be very, very selective. I think it is important now for us curators to be able to educate the public and to direct them in this ocean of images. It’s a bit like having access to all the books of the world. Sometimes it’s better to know one book very well. In the Renaissance, for example, a very cultivated person might have had the knowledge of sixty, seventy, eighty books in a lifetime. Maybe they had a very articulate view of the world because they could focus on and think about what they had seen and read. Sometimes less really is more. I wouldn’t say always, but often enough.

PG: So, in terms of your curatorial program, how does the photography department at MoMA move forward in this vast sea of imagery?

QB: To the extent that I can determine that now, MoMA—and not just the photography department—has to offer a history of art and also a cultural history, which are two different things. Maybe by focusing not only on art, but also on cultural phenomena, we might establish, for example, a relationship between high and low. In the photography department, I think we need to do more thematic exhibitions that don’t focus strictly on art issues but also more generally on cultural issues, which is a slightly different, broader approach. Of course we must continue to do monographic shows, but it is really important not to focus only on such exhibitions. We have also neglected a bit to feature young artists, the generation in their late twenties and early thirties. New Photography, the museum’s annual showcase for emerging photographers and new practices, is definitely something I would like to give a fresh impulse to: change the rhythm by not having it every year, but rather every two years, and on a much larger scale. This will happen in 2015 for the thirtieth anniversary of New Photography.

PG: I was just downstairs in the current permanent installation in your photography galleries. Allan Sekula is on one wall and Stephen Shore is on the other. Sekula’s work is based on a set of ideas in service of a socio-economic cultural critique. Shore, operating from a different set of conceptual ideas, is focused on the perceptual qualities in the photographic image. I wonder if you have thoughts about the distinction— not about Sekula and Shore, specifically—but about the ideological and the perceptual?

QB: I agree with you that photography is about perception of the world, even if we talk about photographers who stage work. But let’s focus on what we could call descriptive or documentary practice. The most interesting photographers in that field are those who manage to find a proper balance between perception and the idea. I was talking about this with Paul Graham a few weeks ago, who said that you can set out with the best possible idea, open your door, go outside, and the world changes that idea. And you have to accept that and shift your expectation to accommodate what you observe and evolve with it. What you produce in the end will probably be quite different from the initial idea. This is what photography is about. It is about having an idea at first and accepting that you’re going to be seduced, in the etymological sense of the word, by the world you’re encountering. Some photographers remain really stiff and rigid. They have the idea. They just want to illustrate the idea. And, then you have the opposite: photographers who go out to shoot without any preconceived idea and then, afterwards, try to put all the pieces of the puzzle together and construct something from their images, which is what has happened in photography since the beginning.

Photograph by Stefan Ruiz for Aperture

PG: How did you come to photography, Quentin? Did you practice? Did you paint or draw?

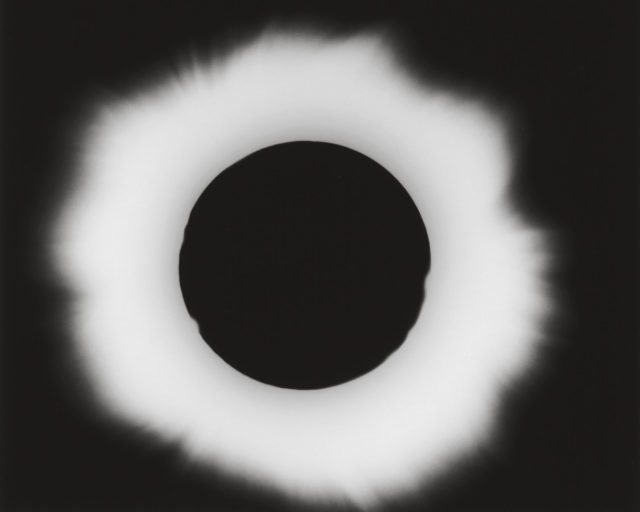

QB: I painted a little. I still draw a little from time to time. I didn’t study art at the university. I started working in the communication business in Paris years ago but soon enough I decided that I had to change. I had to earn my living doing what I really wanted to do, so I applied to a school for curators in France, called Institut National du Patrimoine (National Heritage Institute), a very formal French centralized system. I was interested in twentieth-century photography and art. The photographs of interest to me were scientific images of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—Eadweard Muybridge, for example. That kind of material had, of course, a big influence on modern art. When I arrived at the Musée d’Orsay I was not at all a specialist of photography. I trained myself by opening the boxes in the collection, discovering images, looking at them, having a relationship with the images and the objects because that’s also what the museum is about—images that are objects and have a physical presence. This is how I became a specialist of nineteenth-century photography, even though I was always very interested in contemporary photography.

PG: Do you think the narrative of photography—the history that has been written so far and is being revised and rewritten as we speak—should be broadened to include its relationship to film, as well as other fields?

QB: The answer would be yes, of course, it should be broadened and that is something I have always tried to do, both at the Musée d’Orsay and at the Pompidou, working on the relationships between photography and other art forms: painting, of course, but also architecture, film, and so on. Interdisciplinary looking will help prevent what I would call a “fossilization” of a history of photography as a specific art form, and offer richer approaches more in line with today’s artistic practices.

PG: You talked about your ideas for revamping New Photography, but do you know what your inaugural show at MoMA will be?

QB: Nothing is decided yet. Maybe it will have something to do with scientific practices. I will organize the new display of the permanent collection next February. Every year we change the display of the photography galleries, and I will do something around studio practice—the way photographers and artists use photography to investigate the studio space, using their studios as a playground, a laboratory, a theater, a stage. It will include nineteenth- and twentieth century material, and possibly some video and film.

PG: Are there genres of photography that have not yet been identified or canonized—in the manner of portraiture, landscape, or street photography—such as social-media photography, for example, or surveillance photography?

QB: There probably are. The truth is that the length of time that elapses between the arrival of a new genre and its identification and canonization by artists, photographers, institutions, galleries, and historians is diminishing. I even have the feeling that some of the genres you mentioned—surveillance photography at least—are already part of the art world. Think of the exhibition organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art not that long ago called Voyeurism, Surveillance, and Photography. Paradoxically, one category that has not yet been identified is what I would call “mainstream photography” —stock photographs that you find online and see everyday without actually looking at them.

PG: What about the photobook as its own genre at this point in time?

QB: There is now a serious return to the book form. Collectors are collecting photography books instead of prints. This is thanks to the Internet, and also to the fact that today you can self-publish your book quickly and more easily. Some talented young photographers prefer to edit books of their work instead of finding a gallery or exhibition space. We have to be aware of these ever-changing forms of photography. We will probably see a return to smaller images because we’re all using iPhones. The next generation will be able to read an image of that size but I am not able to.

PG: Of course, there are as many bad photography books as there are billions of bad images in the world today. That isn’t to discount the good books being published, it’s just that there are more to wade through. I keep thinking of Martin Parr’s excellent two-volume history of the photography book. Does the book form factor into any of your overarching goals for this department? And also the Internet, for that matter?

QB: I think we should publish books that include more works from the museum’s collection, because the last real book about the collection was John Szarkowski’s Photography Until Now, published in 1990, just after the one hundred fiftieth anniversary of photography’s invention. I think we should plan to publish a two- or three-volume set of the photography collection. We should also try to put online as many images as possible from the collection. I hope that in four or five years we can provide access to the whole collection online.

PG: What an important resource to have available. That is one way to democratize the collection. One final question: Each of your predecessors is distinguished by what they did for this department. Do you have any sense of what you would like your mark to be?

QB: That would be to leave the museum with a photography department and collection that is more fully integrated into the museum’s collections, more in dialogue with the other departments, and more global in scope.

This article is included in the Winter 2013 issue of Aperture magazine, “Photography as you don’t know it.”