Vision & Justice Online: Ming Smith and the Kamoinge Workshop

For Ming Smith, joining the Kamoinge Workshop was a transformative experience.

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978

Courtesy the artist

Routinely excluded from the mainstream art world, in the 1960s, a group of African American photographers formed a collective to promote and exhibit their work. For one promising young artist, the experience was transformative.

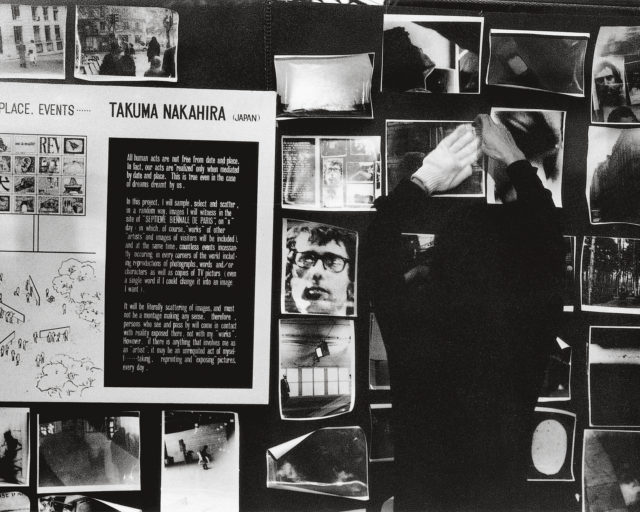

In the early 1970s, Ming Smith was working as a model in New York City but becoming serious about photography. While on a go-see, she made an acquaintance that would change the course of her artistic development: one with Anthony Barboza, a member of the Kamoinge group and currently the group’s director. In due course, Barboza invited Smith to join Kamoinge and she began exhibiting with the group. Through Kamoinge, an association of black photographers formed in New York in the 1960s, Smith began developing her craft, eventually exhibiting with the group as its first female member.

Kamoinge itself began when two separate groups of young black photographers—including Louis Draper, Earl James, and Calvin Mercer, among others—gathered in 1963 to discuss ways of using their work to address the civil rights movement and the troubling conditions of black people in their communities. It was concurrent with other progressively minded black artist groups such as Spiral, also based in New York, which included painters Romare Bearden (whom Smith would photograph in 1977), Hale Woodruff, Norman Lewis, and Emma Amos, among others. Kamoinge was initially mentored by more established photographers such as Larry Stewart and Roy DeCarava served as its first director. More than just a photography collective, Kamoinge (named for a word from the Kikuyu language meaning “a group of people acting together”) was an important forum for creative political activity.

Kamoinge was not as much an organization, strictly speaking, as it was an informal circle of trust, affirmation, and career development. For Smith, just at the start of her practice, the group provided important forms of peer-to-peer discourse, meaningful critiques, and exhibitions. It also provided what can only be described as a methodology of feeling. Draper, in particular, routinely asked to see Smith’s images and offered insightful notes and suggestions. During an era in which black artists were routinely excluded from the mainstream art world, Kamoinge—from one generation to next—exemplified the principle that black artists could not afford to dismiss, or be blind to, important realities within their communities.

The influence of Kamoinge, and specifically of the group’s aspirations for political change, can be clearly seen in Smith’s work. Her photographs reveal the underlying tensions between citizens and communities. She positions her subjects as intimates feeling their way through specific conditions and circumstances, and deliberately invokes this exchange in her images. “The magic of photography,” Smith told me recently, “is seeing and capturing the moment.”

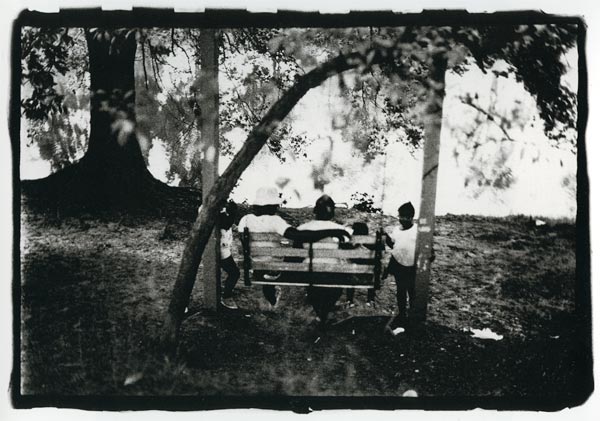

Her photograph Family Free Time in the Park (1982), made in Piedmont Park, Atlanta, exemplifies this feeling, and is characteristic of her work. The viewer who examines this image hoping to find life as the accumulation of cold and pointed denotations will perhaps be disappointed that the photograph does not submit the totality of its implications to those who lack imagination. It is a startling interpretation of a black family placed between hard formal contrasts. There was jazz in the park. It was summer. The black and white clash like thrusts of heat and cold, sounds and silences. Smith, on an afternoon stroll, synced these impressions into an image of feeling and an uneasy beauty, and this treatment correlates with larger societal tensions in Atlanta.

When Smith made Family Free Time in the Park, Atlanta was in mourning. Twenty-eight black citizens—many of them children—had been murdered there between 1979 and 1981, and the city was preoccupied by a pervasive terror. Although Wayne Williams had recently been sentenced for the murders, questions lingered about the credibility of the evidence presented against him. President Reagan had met with city officials and allocated funds for the investigation; the FBI committed nearly forty agents to the effort. Psychics, bounty hunters, and the Guardian Angels had marched into the city offering their services, but left without verifiable clues or a suspect. The city was turned out, and nothing. Centuries’ worth of layers of systemic racism had rendered Atlanta’s black communities vulnerable to the kind of terror that thrives in the darkness. It was clear that invisibility had its consequences.

In 1982, Atlanta had yet to shed the unease, and here a black family attempts triage as the terror of the recent past slumbers. They are present but semi-legible. Veils of partial social erasure cover their lives. Their skins, shaded by darkness, and the children’s eyes, also shaded, are plausible metaphors. Just above, light bristles through the leaves’ stillness and peters out in long edges. The parents have their backs to us. The arch of the father’s arm is a fragile covenant. Traces of sun extend from the large pool of light in the background; the light paces toward the viewer, carrying with it the impression of a nearness that does not exist. This psychological distancing persists even in such an overwhelming light. Ming Smith learned much from Kamoinge, but her photographic vision and this image have lives of their own.

Timeless: Photographs by Kamoinge was published by Schiffer in 2015.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.