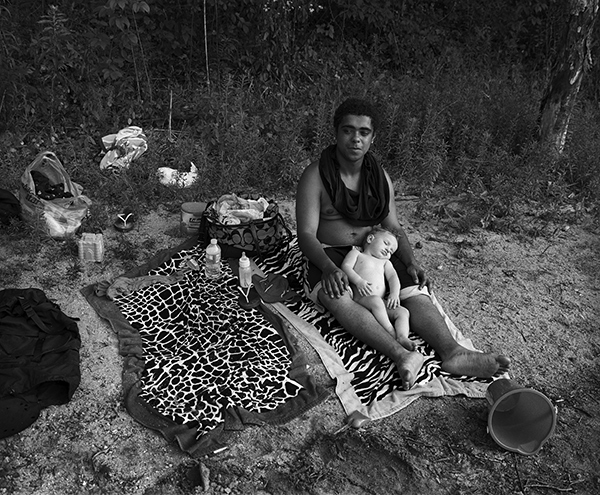

S.B. Walker, Combing hair after a swim, August 2010

© the artist

Although photobooks live and die on the meaningful coherence of selection and sequence, sometimes a single image goes straight to the gist. The last of the beautiful black-and-white photographs making up S. B. Walker’s Walden (2017) does this. Concluding a series that implicitly pits recollections of Henry David Thoreau’s classic paean to simple solitude, Walden (1854), against recent encounters at the famous pond, the final picture offers a rebus for the gulf between Thoreau’s day and ours. In the distance, we see a topos of nineteenth-century pictorialism, a bosky lakeshore, a strip of fog, and a mirror image of the shore in still water. This softened world and its reflective quietude promise to cure, counter, or redeem the clanking tumult of modernity. But in the foreground this pictorialist revival gives way to a sampling of twentieth-century abstraction. Reflected sky and melting ice merge in a white expanse, on which an even whiter plastic Target bag lies crumpled. The result is a mash-up of Kazimir Malevich, Marcel Duchamp, and Jasper Johns, a white on white, interrupted by a target-covered readymade. Taken as a whole, the picture strands us between incompatible modern paradigms.

© the artist

Did Walker intend all this? I have no idea. But his book unquestionably meditates on historical rifts, on the cruel contradictions of modernity and the clever descents of modernism. The historical rifts leave Walden Pond in an incongruous state. The pictorialist background refers to a prior century but also signifies the restorative pleasures that the pond continues to deliver. Walker’s photographs show us people sunning, swimming, reading, and cavorting along the pond’s shores. In his generally fine essay accompanying the photographs, the great Alan Trachtenberg remarks on “the absence of signs of human pleasure,” but it seems to me they are rather plentiful. These pleasure seekers are sundry in appearance and style, making the book an occasion to celebrate the values of diversity and tolerance. But as the Target bag reminds us, modernity has not been kind to the ecology of Walden Pond or to the sensible politics of Thoreau. The book abounds in traces of ecological callousness and degradation. People have come to enjoy precisely what their enjoyment will destroy. The Target bag may be a witty riff on modern art, but it is also trash.

Many of the book’s photographs follow this semantic structure, juxtaposing signs of recreational pleasure with signs of banality or loss. We encounter an image of a woman playing a didgeridoo, surrounded by tree roots exposed by erosion, with plastic fencing sagging behind her. The prospect of this woman finding a quiet place by Walden Pond to play her instrument warms the heart, but the land itself looks trampled and bleak.

© the artist

Despite the visibility of inclusiveness and recreation, and the enlivening rhythm of the book’s layout, the book has a melancholic tenor. One could ascribe this to the poignant traces of ecological degradation, imaginatively measured against a healthy Walden Pond of yore. But for me that’s not quite right. For me, the melancholy stems less from an attachment to a certain pond and more from an attachment to a certain kind of photography. The photographs are saturated with signs of the medium’s past. Echoes of the likes of Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Sally Mann are rife. Here is a photographer who has learned from the pantheon what gritty realism you can make of a tattooed amputee, what haunting banality you can get from an artificially illuminated football field, and what uncanny disquiet you can extract from a dark bag left in the woods. The echoes are in the captions as well as in the photographs. The title of Black man, white baby (2013), a picture of two figures relaxing together on a zebra-print towel, seems like a caption from another time.

© the artist

S. B. Walker knows his craft. He knows how to make photographs, and how to string them together. On this score, Walden is a remarkable achievement. But here’s the rub: the photobook is more than craft. For its definitive practitioners, the photobook has been a timely intervention, a vital cultural shock. Walker Evans, William Klein, Frank, Arbus, Mann: their photographs, when introduced to the world, looked unfamiliar and stirred up trouble. Yes, I know: this is an absurdly high bar, and if I could make photographs as well as S. B. Walker can, I would probably give up my day job. But as I went through his book, I found myself wanting the photographs to offer more critical reflection on the distance between 1950s and 1990s photography and what photography must be today. Signs of the digital life-world appear in Walker’s book, but only as an iconography of people using smartphones.

© the artist

Don’t get me wrong: employing older technologies is by no means a capitulation to dumb nostalgia. Mann used large-format black-and-white to blow the roof off family photography. But when encountering a photobook I want to experience the choice of means as working in concert with the historical argument the pictures relate, and that argument must make sense of the present. As I tell my students, to emulate Robert Frank is not to make photographs that look like his; it is to pursue the hidden logic and necessary means of one’s own time. I’m not sure that Walker’s book shows us that.

Walden was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2017.