What Is Street Photography Today?

An exhibition in New York strives to define the possibilities of street photography today—and to tell us something about the state of our world.

Debrani Das, Harmony in Varanasi, 2023

Courtesy the artist

The street and the camera were destined to collide. In retrospect, it seems obvious that the first photographs that managed to freeze objects in motion would be taken on the bustling streets of newly industrialized nineteenth-century cities. That era belonged to the crowd, and to the savvy navigators of the endlessly renewable theater of sidewalks and boulevards the world over, those flaneurs whom the poet Charles Baudelaire, in his essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” pegged as one of the nineteenth century’s most fertile archetypes. Baudelaire called for an art that would dive headfirst into the bracing water of the everyday. Impressionism followed, with its gauzy tableaux of bourgeois life, but in time it became clear that it was not the likes of Baudelaire’s titular, now-forgotten painter who were best suited to document the upheavals of the modern era. The pace of everything was quickening, and the newfangled camera was the perfect tool to slow things down, trapping the chaos in amber. Photographers became the ultimate flaneurs, shaping our collective vision as they wandered through the world.

Courtesy the artist

Street pictures soon became practically synonymous with serious photography. The introduction of the fast, handheld 35mm Leica, in 1925, disencumbered roving shutterbugs from their bulky gear, allowing artists like Alexander Rodchenko to make a new kind of image that was as dynamic and spontaneous as the streets themselves. After that, it was off to the races. In 1952, inspired by the Surrealists’ obsession with chance encounters and striking juxtapositions, Henri Cartier-Bresson coined the indelible phrase “the decisive moment.” There followed Robert Frank’s Beatnik-era, dirge-like book The Americans; the epochal exhibition New Documents, featuring Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand, at MoMA, in 1967; the Pop art–adjacent work of William Eggelston, which carved out space for previously déclassé color photography in hallowed museum halls; and, finally, the postmodern turn in the late 1970s, which laid the groundwork for the innovative scenes by Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Jeff Wall, deploying what were by then well-worn street photography tropes in the service of creating cinematic images that blended fact and fiction or were wholly fabricated for the camera.

Courtesy the artist

© the artist and courtesy Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York

© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation

Or anyway, that’s the usual history of street photography, made up of mostly white male Westerners. While I could have mentioned the work of photographic giants like Helen Levitt, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Vivian Maier, Gordon Parks, Daidō Moriyama, Mohamed Bourouissa, or others who have a rightful place in the street photography canon, this was pretty much how the story was relayed to me, as I studied photography in college. Clearly, that blinkered history needed to make room for some heterodox voices.

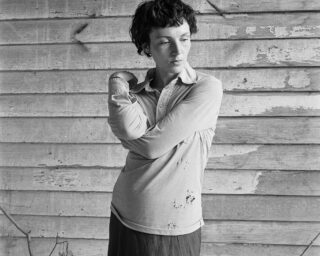

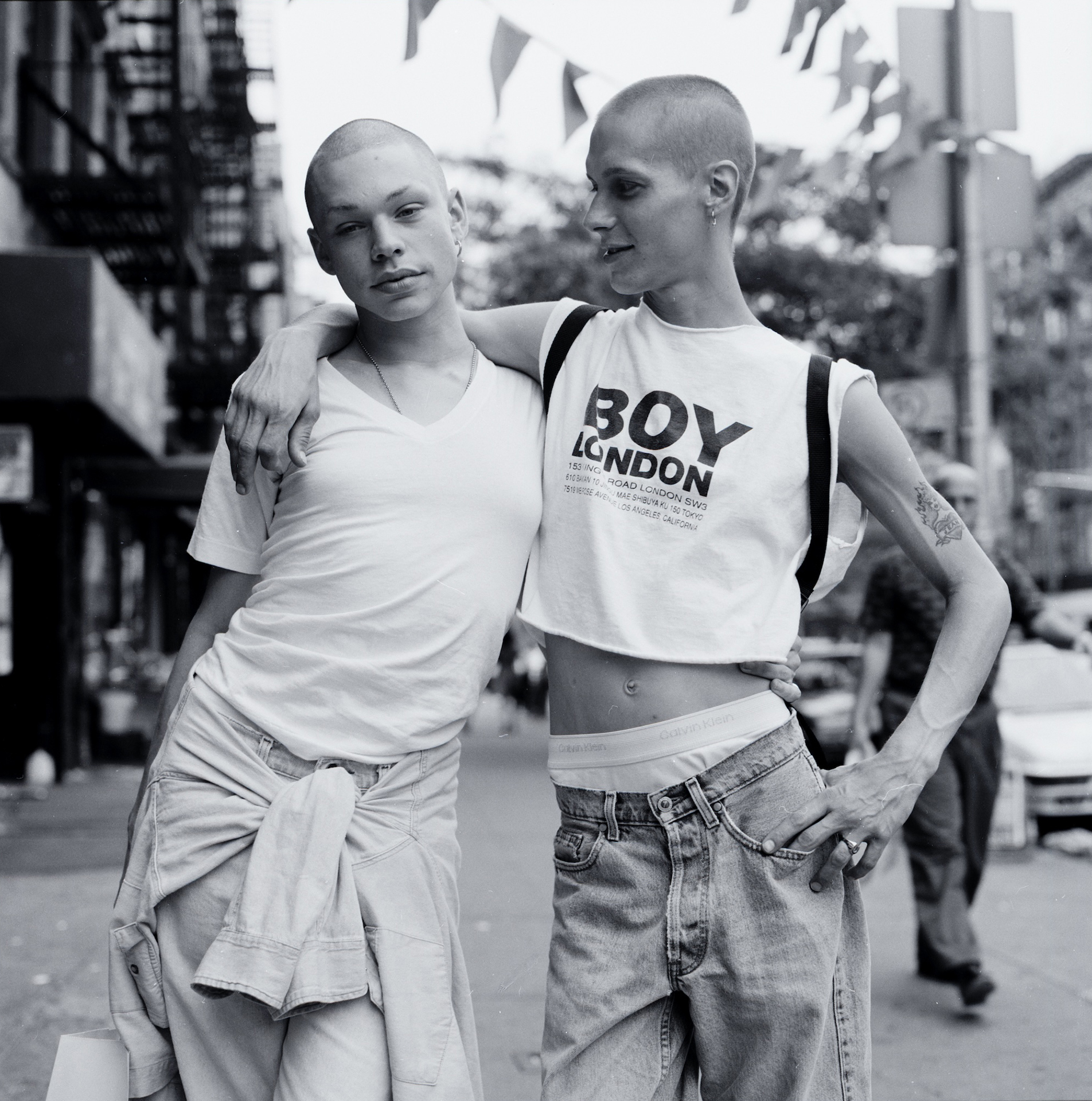

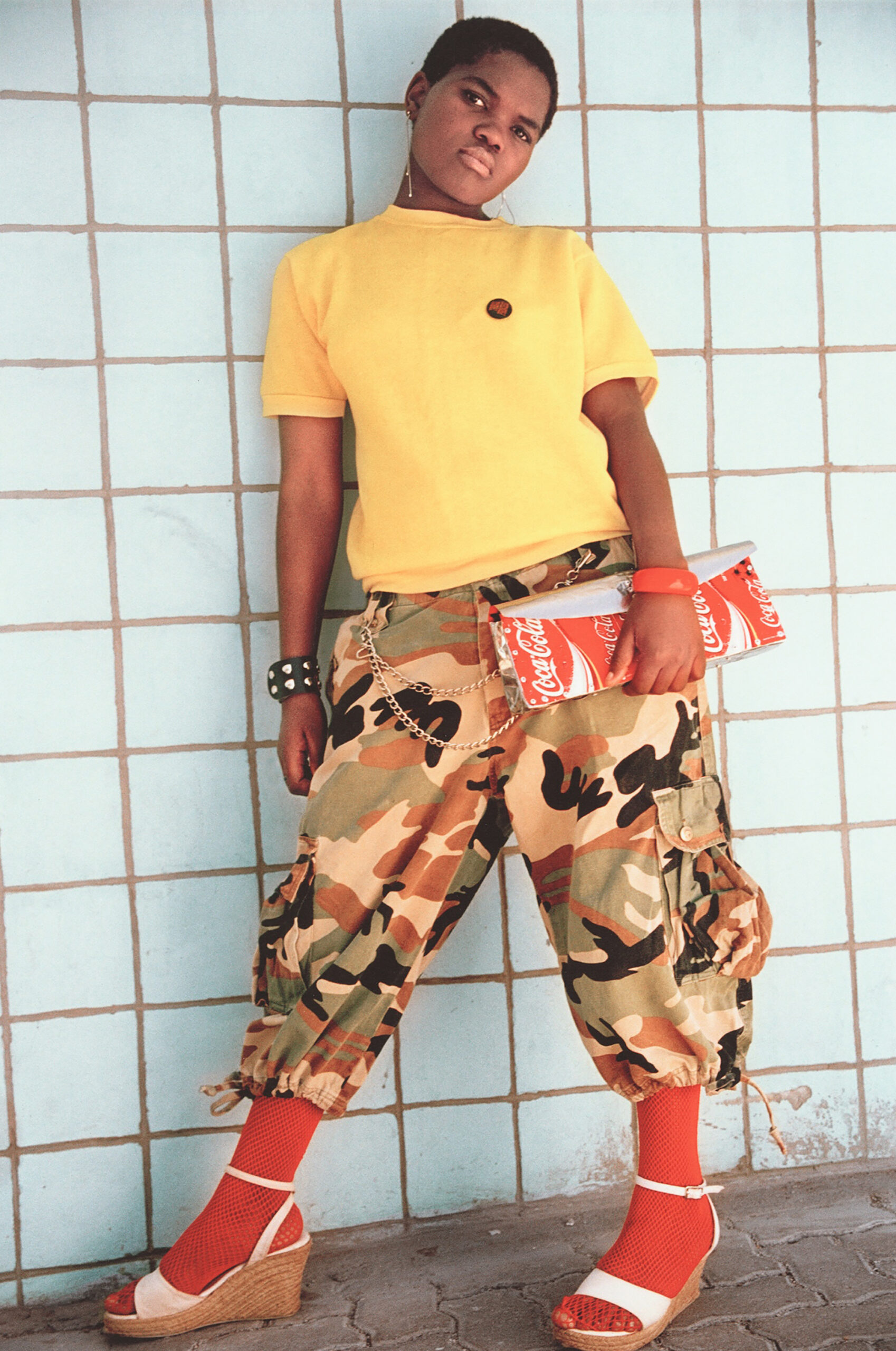

A sprawling new exhibition, We Are Here: Scenes from the Streets, currently on view at the International Center of Photography (ICP), in New York, has this aim. The show, curated by Isolde Brielmaier, with the assistance of Noa Wynn, features thirty-four artists working in twenty-two different countries. Some of the work stretches back as far as the 1970s (in a show-within-a-show that the curators have dubbed “On the Shoulders of Giants,” which focuses on New York street photography), but the lion’s share of the pictures on view are from the last ten years or so. Arranged in four broad categories—street style, neighborhood and community, protest and advocacy, and urban landscapes—We Are Here strives to provide a picture of the state of street photography now(ish), and to tell us something about the state of our world as a result.

Courtesy the artist

We Are Here is admirably diverse, and many of the pictures are great. Highlights include the lush, wacky, fashion-forward work that Feng Li has been making on the streets of Chengdu, China; Romuald Hazoumè’s cheeky sculptural typologies of laden bike riders in Benin; the oneiric pictures of 1990s Saint Petersburg by Alexey Titarenko; a collection of era-defining 1990s Japanese street-style pictures that Shoichi Aoki shot for his magazine FRUiTS; and exuberant pictures of children’s play in gritty 1970s New York by graffiti documentarian Martha Cooper, which elaborate on earlier projects by Helen Levitt and Arthur Leipzig. Yet the exhibition is also dogged by a nagging question: Is twenty-first-century street photography hopelessly outmoded?

Street photographers fall into essentially three sometimes overlapping camps. First are the descendants of Cartier-Bresson, who stalk the sidewalks in the hope of catching some serendipitous urban gestalt, which is either compositionally gorgeous, weirdly poignant, funny, freighted with sociopolitical import, or some combination thereof. Second are those engaged in a long-term project of social stock-taking, like Walker Evans or Robert Frank, who use the street to a weave semi-personal narrative about the character of a time and place. (This place, historically, has been America, though there are notable exceptions to be found in projects like Paul Graham’s New Europe.) Third are those photographers who inflect their street photographs with their personal presence, whether formal or emotional, such that the line between the inner and outer world becomes hopelessly blurry: the photographic equivalent of New Journalism, with Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander at the helm rather than Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Aside from the work in We Are Here that is best described as reportage—namely the pictures of protest movements grouped together under the “protest and advocacy” subheading—much of the exhibition consists of pictures that rehash previously extant styles of street photography, but in an era that can no longer be called modern. I’ll leave it to others to tell what our era could be rightly called—“postmodern” is entirely too retro—but we can be certain that the space that most exemplifies it is no longer the street. Perhaps, as the anthropologist Marc Augé argued in his 1995 book Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, it is instead one of the featureless spatial products of globalization—airports, supermarkets, shopping malls, chain hotels—that form a fractured, yet uncannily contiguous purgatory, scattered across the earth. More likely it is the space right under your nose, where you are reading this text: cyberspace.

Given the pull that the Internet has over our daily lives, it is almost shocking how little technology shows up in the pictures on view at ICP. By my count, there are only five pictures in which smartphones even appear, and just two of these show people gazing into them, perhaps the most commonplace sight in any city anywhere. Beyond that, almost none of the images contain technological tells that they were taken anytime this century. On the production end, only Michael Wolf, who made a collection of found street photographs using Google Maps, has utilized technology that would be unfamiliar to the modernists. A feeling of anachronism prevails.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Even people’s manner of dress, which Baudelaire insisted was key to taking the temperature of any age, looks temporally fuzzy in the exhibition. Save for some bold, funky takes on traditional African garb captured by Trevor Stuurman in Dakar, Senegal, a few cutting-edge looks found in Feng Li’s pictures, and the presciently chic fashions captured in South African cities by Nontsikelelo Veleko twenty years ago, the clothes people wear are mostly a drab parade of generic causal wear, the fast fashion and sportswear slop that sloshes out of the globalized garment industry trough. The most futuristic looks in the bunch hail, paradoxically, from the past—Aoki’s pictures of Japanese youth taken nearly thirty years ago.

Perhaps the former sense of technological anachronism is an indication that contemporary street photographers are averse to depicting the banalizing aspects of our technological society, which have steadily made the world uglier, and the public sphere less vibrant. (Even back in the 1990s, an aging Helen Levitt lamented: “Children used to be outside. Now the streets are empty. People are indoors looking at television or something.”) Maybe, similarly, street photographers avoid photographing excessively trendy fashionistas because they fear their pictures will be defined by the clothes they capture. Or the feeling that time is out of joint in this exhibition is a telling sign of the kind of cultural stagnation that Mark Fisher, citing the Italian philosopher Franco Berardi, called the “slow cancellation of the future.” Likely all of the above. But it is also the case that as we exited the modern age and migrated the dynamos of capital and social life online, the world has begun to mostly transform off stage, becoming governed not by the life of the street, but through subtle shifts in the digital pleroma.

Courtesy Farnaz Damnabi and 29 Arts In Progress gallery

Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson

In some ways, this is an extension of an old problem. Walter Benjamin, in his 1931 text “A Little History of Photography,” complained that the photograph “can endow any soup can with cosmic significance but cannot grasp a single one of the human connections in which it exists.” To elaborate on this, he quotes Bertolt Brecht, who observed that “less than ever does the mere reflection of reality reveal anything about reality. A photograph of the Krupp works or the AEG tells us next to nothing about these institutions. . . . The reification of human relations—the factory, say—means that they are no longer explicit.” But, in ways that Benjamin and Brecht could scarcely have imagined, our situation has become even more abstract. If a photograph could reveal “next to nothing” about a world run by the factory system, consider how much less it must reveal about a world run by algorithms.

Courtesy the artist and Collective 220

We now live in the era of the so-called black box, ruled by systems whose internal workings are opaque even to their creators. Our sociopolitical world is increasingly governed by social media algorithms which have sowed division and ignited civil unrest, either as the result of an unhappy accident of their flawed designs or through the malicious machinations of state actors and shady billionaires. (Even street protest movements, which We Are Here puts forward as triumphant engines of social change, have become social media–engineered phenomena, which rarely achieve their stated goals, and, conversely, give political ammunition to forces that oppose them.) As the filmmaker Adam Curtis, in his BBC documentary Hypernormalisation, and the journalist Vincent Bevins, in his book If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution, have both pointed out, the Internet age makes it easy to get people to the streets, but has not made it easier to figure out what to do after they get there, which is the tricky part). The strings of our economy are pulled by supercomputers running high-frequency trading algorithms like BlackRock’s Aladdin, which now manages in excess of twenty-one trillion dollars in assets, likely more than the GDP of any country on earth. The truth value of images themselves, and their impact, have never been more questionable, as we are fed a constant slurry of algorithmically optimized and increasingly artificially generated “content,” managed by vast server farms that are quietly sucking our aquifers dry and rudely shoving aside the pesky carbon emissions targets that stand in the way of promised progress. Soon, it seems, the whole of our reality might be shaped by our encounter with a fundamentally alien, super powerful AI. How can we possibly hope to capture this world from street level, using as blunt and as literal a tool as a camera? Perhaps we must return to Baudelaire’s plea for the creation of a contemporary vision of contemporary times, and try to chart a new way forward.

We Are Here: Scenes from the Street is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through January 6, 2025.