Who Was Richard Avedon?

Avedon transformed notions of style, celebrity, and photography itself. A new book by Philip Gefter argues for his place among the most important artists of the twentieth century.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Richard Avedon with Carmel Snow and Marie-Louise Bousquet, Dior Showroom, ca. 1946

Magnum Photos

Often, the individuals who are best known and most public are, in fact, the least knowable and most inscrutable. The masks that ensure their legends often obscure their tortured private lives. Among photographers, few were more conspicuously famous or notoriously private than Richard Avedon (1923–2004). Following a meteoric rise as a young fashion photographer at Harper’s Bazaar in the late 1940s, and later at Vogue and other magazines, the intensely driven Avedon glided through mid-century New York high society with the glamorous authority and savoir faire of a movie star. He transformed notions of style, celebrity, women’s fashion, and photography itself.

But around 1969, after nearly two decades of literally dominating the covers and glossy pages of leading fashion magazines, Avedon turned abruptly and increasingly to innovative forms of photographic portraiture—often large, minimalist, and unsparing in detail. And it was those experimental portraits, more than his groundbreaking fashion work, that ultimately won Avedon the plaudits which he so craved from art galleries and museums.

In the new book What Becomes a Legend Most: A Biography of Richard Avedon, noted photography critic Philip Gefter explores the intricate backstory of Avedon’s private life and the evolution of his career to make a case for him as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century.

Courtesy Lizzie and Eric Himmel

Brian Wallis: You have just published a massive biography of Richard Avedon, a project that has absorbed you for over five years. Let’s talk about the project of biography in general. Does writing a biography make you end up loving or hating your subject?

Philip Gefter: I went through stages, as with any relationship. There were moments when I loved him. There were moments when I was completely annoyed by him. There were moments when he disappointed me. And then, there were moments when he was utterly redeemed. [laughs]

Wallis: After all that, what do you think is the value in tracing someone’s life? What did you learn, and what do you want to communicate to readers?

Gefter: Well, that’s a good question. In the case of Avedon, specifically, I had always felt that he was a far more significant artist than he was generally considered. In fact, it was only toward the end of his life that he was finally acknowledged as such. And I always was curious about him personally: what was the combination of qualities that formulated his unique sensibility? That was really the essential question for me, that’s what I set out to try to answer.

Wallis: In arguing for Avedon’s cultural significance, you say at one point that there were various forces arrayed against him, forces that would deny him his status as an important artist for most of his life. And you say at the very beginning of your book that your principal goal is to make a case for Avedon’s rightful place in “the pantheon of twentieth-century arts and letters.” Why is this important to do? And why now, in particular?

Gefter: From the time I went to art school at Pratt in the early 1970s, I was aware of a general prejudice against photography. It was considered a second-class medium, not much more than a graphic art. And during the ’70s, I watched with interest the elevation in stature of photography in the art world. So I always felt the need to defend photography as a medium. I studied and understood its history and was fortunate enough to meet many interesting photographers. I’ve always loved the photographic image. In the end, I truly believe that photography reflects something profoundly existential about who we are.

That said, the reception of Avedon’s work in the 1970s and ’80s seemed to me to be representative of the prevailing derogatory attitude toward photography. And his struggle to be recognized as an artist was not his alone. Like many photographers of that time, Avedon suffered a genuine artist’s quest to have his work recognized. And he had to endure a number of prejudices about the medium he chose.

In particular, he suffered the prejudice of being a commercial photographer in the art world, where there was a very distinct church-and-state divide between art and commerce. Today, of course, art is commerce. But fifty years ago, there was still some semblance of integrity about the making of art without the goal of simply making money.

Magnum Photos

Wallis: But by that time, Avedon was a very successful photographer.

Gefter: Yes, Avedon was one of the most famous photographers in the world at that time, but he was also known as a fashion photographer which, in the art world, was a joke. So, he tried various approaches to hurdle that negative reputation. For instance, there was Avedon’s show at Marlborough Gallery in 1975, which was a signal moment in his career and, even in the photography world, was a bit of a phenomenon. He showed his large, wall-size group portraits for the first time together. But art critics dismissed the show as high-style formulaic imagery that didn’t really rise to the level of Art with a capital A.

So, one issue I wanted to raise in this book was this: At what point would the critics and scholars finally acknowledge that Avedon’s approach was not merely a formula but an artist’s signature style? That was something I was intent on putting forward.

Wallis: Why was Avedon’s exhibition of portraits so controversial?

Gefter: In the 1970s, in New York in particular, street photography and new forms of documentary photography were ascendant. Nothing could have differed more from Avedon’s approach. He was a studio photographer, and his work was all set up—even the spontaneity was contrived in advance. And that whole approach to photography was thoroughly dismissed at the time. Later, in the 1980s and through the early twenty-first century, studio practices were taken seriously by artists and photographers, and given increasing stature in critical writing and thinking. But that required a substantial shift in thinking about photography as art.

One other thing: I had always believed that Avedon insinuated himself into the art world to satisfy his own ambition or ego. But I was surprised and relieved to learn that, for every single museum show he had—at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum, and the Met—he had always been invited by the curators or museum directors. In fact, even in the case of the Marlborough show, he was invited. He didn’t go to them. They went to him. That’s a significant shift in mind because, in fact, in some ways he was accepted by aspects of the art world and its institutions—more so than we’d thought previously.

Wallis: On the other hand, from your detailing of his relationship with John Szarkowski, the photography curator at MoMA, for instance, it’s clear that these were long-running campaigns of flattery and persuasion by Avedon, through which he attempted to capitalize on the rising interest in photography by certain curators at specific museums.

Gefter: Yes, that’s true. When Dick and John Szarkowski met in the early 1960s—I’m going to call Avedon “Dick,” if you don’t mind. I mean, everybody called him Dick. I think of him as Dick, not that I knew him.

Wallis: I think after a five-year relationship, you’re entitled to do that.

Gefter: [laughs] Yes, well . . . When Dick and John Szarkowski met in the early ’60s on the occasion of the Jacques Henri Lartigue show at MoMA, they established a very cordial relationship. In the late ’60s, Szarkowski went to Dick’s studio several times; he had come to recognize Dick’s work as being significant and, in fact, invited him to have a retrospective. Then, Dick and John began a conversation about what this retrospective would be. The problem is that Dick, because he was obsessive and self-promotional—and wanted to be in total control of everything related to his work—eventually alienated Szarkowski. Two years into this conversation about the retrospective he would have at MoMA, Dick agreed to have a retrospective at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Well, this didn’t sit well with John Szarkowski at all, because it preempted the uniqueness of his planned show at MoMA. And John was very territorial. So, understandably, that began a process of alienation. Thereafter, Dick was never really accepted at MoMA. Having spoken to the curators there going back to John’s era, I know that they basically dismissed Avedon as being too commercial. They simply dismissed his work. They didn’t acknowledge it as art.

Wallis: That dismissal must have been devastating to Avedon.

Gefter: Yes. I think he spent the rest of his career trying to get John Szarkowski’s attention. He did have a small exhibition at MoMA in 1974. Finally, John deigned to give Dick a single room on the first floor, where he exhibited a small series of portraits of his dying father. But it was nothing compared to the planned retrospective, which was supposed to be a large show covering several galleries.

Wallis: So, instead of focusing on Avedon’s incredible fashion photography, Szarkowski presented his own version of Avedon, as an incisive documentary portraitist in the mode of Diane Arbus.

Gefter: Right. That’s an interesting point. I never thought of it exactly in those terms.

Courtesy Earl Steinbicker

Wallis: In the case of his only show at MoMA, it also seems like a punishing gesture on Szarkowski’s part, one that focused on Avedon’s own self-loathing and self-doubt by forcing him to confront the incriminating stare of his dying father.

Gefter: Well, I think Avedon was trying to work something out with his father. I mean, he hated his father. His father was autocratic and dictatorial, and he tried to teach Dick some very hard lessons as a child. Clearly, Dick was not the son that his father wanted. I mean, Dick was scrawny, unathletic, pensive, and poetic. And his father wanted a “son.” I mean he wanted a guy, a tough guy.

So, while you may perceive in Avedon’s portraits his father’s withering stare, I see it differently. I think that he was watching his father wither away, to the point where his father had no more control of himself as a person dying. That’s my take.

Wallis: That’s brutal. And an interesting take on Avedon’s portraits in general. What distinguishes his portraits as significant to you?

Gefter: Avedon was of the generation that was on alert to the profound threat of the atomic bomb. And more and more, I think he started photographing his subjects like specimens under the forensic scrutiny of his lens, trying to identify a strain of existential dread that runs through the species at the thought of our annihilation.

No one is smiling against the white nuclear backdrop in his portraits. I don’t think he was aiming for emotional contact with his subjects—as compared with, say, the psychologically embroiled approach of Diane Arbus. That was not what he was after. He was after a clearer, more clinical, more objective observation consistent with the postwar, postnuclear condition. I don’t know that he conceived it exactly the way that I’m describing it. But I think that he did bring this forensic attention to the people he photographed.

He also endured being considered a celebrity photographer for years. And it irked him, understandably, as he got older and became more intentional about his work. He would say, “Don’t think about who they are, just look at their faces.” And what he meant by that is that we are all going to die, whether by nuclear annihilation or natural causes, whether we are the former king of England or the most glamorous actress in the world.

Wallis: What, then, did Avedon mean when he said that all his portraits were self-portraits? Was that an arrogant way of describing self-expression or was it, again, a competitive way of dominating other people?

Gefter: Well, not only did he create a visual pantheon of celebrities, he also photographed the anonymous everyman in the American West, and everybody in between. So, I think he was definitely taking his own measure against the person he was photographing.

But in terms of the portrait as self-portraiture, his body of work manifested a direct, clear-eyed approach, stripping the frame to nothing but a face-to-face confrontation with his subject. The visual economy and the straightforward elegance was pure Avedon. That was his signature. That was the artist in the work—hence the self-portrait. It isn’t arrogance. In all art, you see the identifying traits of the artist. In the genre of portraiture in photography, look at Nadar, or Julia Margaret Cameron, or August Sander—each body of work is a self-portrait of that artist.

Wallis: But Avedon’s portraits often seem artificial, soulless, or even mean-spirited. How do you align that attitude with his proud description of them as self-portraits?

Gefter: Well, I think Dick struggled his entire life with his self-esteem. It was a complicated thing. He had enormous confidence in his work, in his eye, in his sensibility. But his self-esteem was constantly on a roller coaster. He endured prejudices as a child. He endured anti-Semitism, and I think he endured homophobia.

So, that mean-spiritedness some people claim to be characteristic of his work wasn’t intended to make other people look bad. Rather, I think he was searching in the faces of others for that strain of existential dread that he felt himself. Maybe it was a kind of projection onto the visages of the people he was photographing. I think that is also what he was talking about in terms of his portraits being self-portraits.

Courtesy Sam Shaw Family Archives

Wallis: How would you compare that forensic projection in his portraiture to the seemingly light-hearted and spontaneous spirit he evoked as a fashion photographer?

Gefter: One of the key things I discovered about Avedon, which was key for me as his biographer, is that as an adolescent, he wanted to be a poet. That was a very serious pursuit for him throughout his teenage years. He was avidly writing poetry, and had his work published in newspapers and magazines. When he was seventeen, he won first place in a New York City–wide high-school poetry contest. And he was the coeditor of his high-school literary magazine—with no less a classmate than James Baldwin. But at some point, he was swatted down by a high-school teacher who said that Dick’s poetic language was largely derivative, the result of the magazines he was reading at home. That comment affected him so profoundly and adversely that he just didn’t have the courage to stay with it.

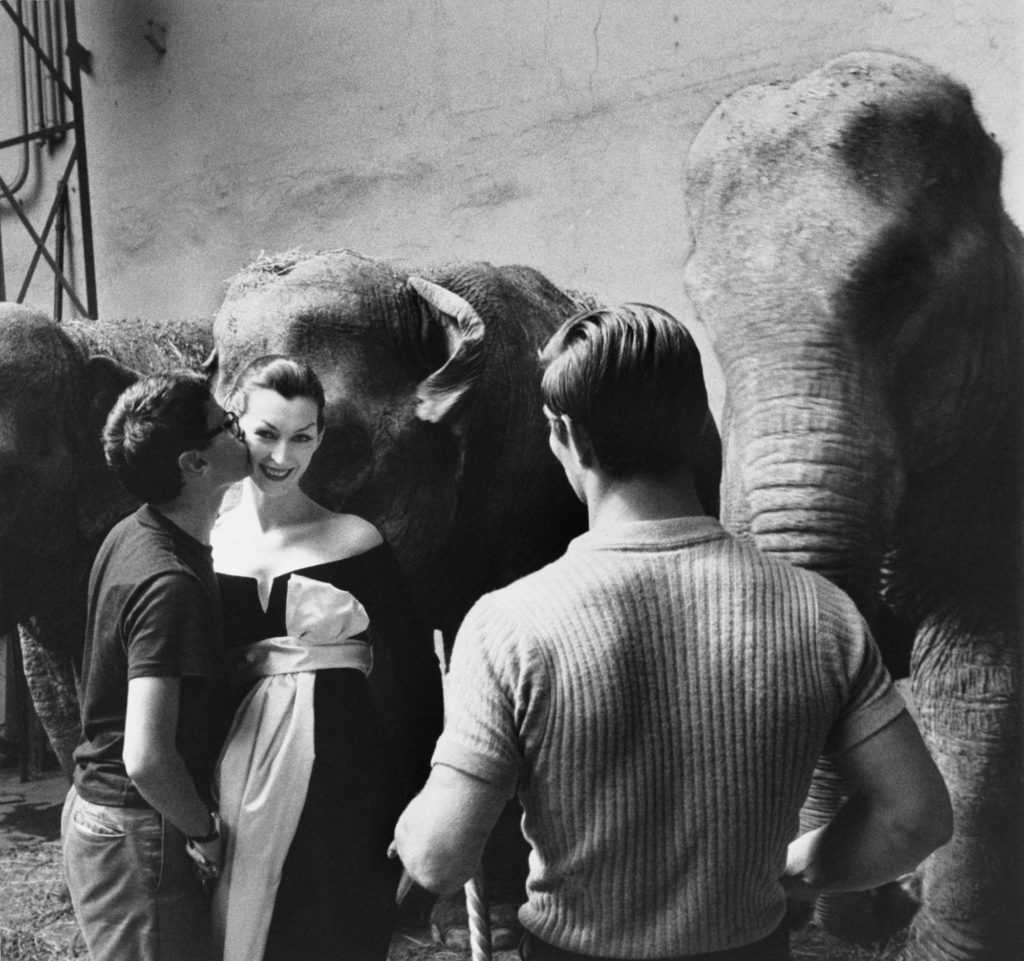

So, I think he brought to his early fashion work this lingering poetic impulse. This is one of the unique ingredients that helped him to revolutionize the fashion photograph in the 1950s. He brought the model out of the studio and into the street—not that he was the first to do so—and he did that with élan, against the spectacular backdrop of postwar Paris. He said, “My Paris never existed. I fabricated it.” Not out of whole cloth exactly, but out of swatches of Ernst Lubitsch, the films of René Clair, the songs of Cole Porter, and the movies of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. He became a kind of impresario of the fleeting visual metaphor, as if a breeze always seemed to be blowing through the frame in his early fashion work. There’s a special kind of spontaneity he was able to achieve, in which the highly constructed and artificial image is made to appear entirely authentic. He said, “I was photographing my own elation. And it got whipped up to the point where I was able to give some emotional dimension to the couture itself.”

Wallis: Was this improvised spontaneity in fashion also the basis of what you call “the Avedon woman”?

Gefter: Yes. “The Avedon woman” is not my term. It was an actual phrase that was used, a kind of cultural trope in the ’50s. The Avedon woman was perceived as a free-spirited, imaginative, curious, provocative, slender, almost androgynous and very urbane female figure. And you can see that type being formed in the models he chose, especially Dorian Leigh, Dovima, and various others. I consider Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly in the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s to be the quintessential Avedon woman. Irving Penn famously said, “Avedon’s greatest creation has been a kind of woman. She’s a definite kind of person. I know her. I’d recognize her if she walked into this room. She’s sisterly, laughs a great deal, and has many other characteristics. . . . It’s a kind of woman I’m talking about projected through one very powerful intellect and creative genius.”

Wallis: What do you think was so appealing to Avedon about fashion photography in the late 1940s, as opposed to other applications of photography he could have pursued?

Gefter: To go back to the notion of the poetic impulse, I don’t think fashion was what Dick wanted to do, necessarily. I mean, what he really wanted was to be part of the cultural life surrounding fashion. Initially, when he was twenty-one, he made up his mind to work for Harper’s Bazaar, and he just sort of bulldozed his way in. In a way, that was very impressive for a young ambitious kid.

Harper’s Bazaar was one of the best magazines when he was growing up, and they were publishing really good literature. His parents subscribed to it. So he would be reading short stories by Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner. Christopher Isherwood published Sally Bowles in Harper’s Bazaar in 1938.

The magazine was a way for Avedon to understand serious culture in a very direct way. He took fashion as being part of that world, and made something of it, and was being paid for it. But ultimately, that wasn’t his goal as an artist. I think portraiture was a much clearer, more direct way for him to bring his poetic observational impulses to his work, but that only came later.

Wallis: Well, that turn toward portraiture—if you want to call it that, since he never really gave up fashion—seems more evident after about 1959, which, as you note, was the year that Robert Frank’s book The Americans was published. And since you have also written a book titled Photography After Frank [Aperture, 2009], are you positing a general shift around 1959 toward a very different approach to thinking about photography as an art form?

Gefter: Yes. It’s a very good question, since both Robert Frank and Dick published books in 1959—Frank’s Americans and Avedon’s Observations. At the time, Dick was well aware of Frank. Not because Frank was prominent. In fact, nobody really knew who Frank was outside of a very small coterie of artists and Beat poets in Downtown Manhattan. But Frank had studied briefly with Dick’s mentor, Alexey Brodovitch. And Brodovitch even wrote one of the recommendations for the Guggenheim Fellowship that enabled Frank to make The Americans. And so, Dick was aware of him. But Dick was uptown and out in the world, and Robert Frank was downtown and quietly doing what he was doing. Still, Dick understood instinctively that Frank was the real thing: he was an artist and a photographer’s photographer.

When The Americans was published, it was a true artist book, authentic documentation of America as Frank was experiencing it. It was a modest publication, but it was something. And Dick recognized that.

Meanwhile, in the very same year, Dick published this very splashy coffee-table book—with a fancy slipcover, and pedigreed to the nth degree. Alexey Brodovitch designed it. Truman Capote wrote an essay. And the people Dick photographed were celebrities. So it had all the right elements to be a pop-cultural event. And it was well-received by the general public. But it was fatuous.

Courtesy the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Wallis: Ouch. Then Avedon’s second book, Nothing Personal, in 1964, was an attempt to use his photography to make a statement about the urgent and topical issue of Civil Rights. And throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Avedon kept trying to make these more socially engaged works, but they often came off as misfires. He seemed to fit the model of what Tom Wolfe called a “limousine liberal,” well-meaning but out of touch. How do you assess the meaning and value today of these quasi-political works?

Gefter: I posit in my book that Nothing Personal was Dick’s direct response to The Americans. What Dick was trying to do, the only way he knew how to do it, was to “portraitize” a set of social issues of that time. He went down South and photographed individuals who were directly involved with or who represented the Civil Rights struggles. Nothing Personal was well-intended, but as an artist, Dick had not yet come into focus. He was groping. I consider it a worthy first draft in the evolution of his more realized artistic intentions.

He was not very successful at this new, more intentional approach to photography until he began his mural portraits in the late 1960s. The first project, in 1969, was of the Chicago Seven, the antiwar protesters who were accused of conspiracy to disrupt the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. That panoramic portrait—of Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, Tom Hayden, and the others—certainly crystalized some of the key social and political conflicts in the United States at that time. In that work and other examples of his radical portraiture—including his mural of the Warhol Factory members, and his series of portraits of leading political figures, which he published as “The Family” in Rolling Stone in 1976—constituted a very systematic attempt to create a new kind of portraiture. And he did. I mean, no one had ever seen portraits like those before. They were literally larger than life; they became not only documents but monuments, in a way. I think that Dick’s portraiture became much more intentional after that.

Anyway, Dick was always looking over his shoulder at Robert Frank and wanting his approval. And Frank always considered Dick a “Sammy”—based on the character Sammy Glick in Budd Schulberg’s 1941 novel What Makes Sammy Run?, which became a film in 1959. A Sammy in Robert Frank’s day would be what a yuppie was in our day.

Wallis: It’s funny, when I read that in your book, I recalled that the photographer Louis Faurer, who was close with Robert Frank at the time, used to mock Frank by calling him a Sammy.

Gefter: I wish I had known that. [laughs]

Wallis: Avedon’s portraits of Robert Frank and June Leaf seem like the absolute antithesis, in some ways, of his fashion work. But at the same time, you see what Avedon was doing is exactly what he did in his early fashion work, which is finding fashion wherever it exists in daily life, and acknowledging the sort of disheveled nature of Frank and Leaf as the new prototype, the new beauty.

Gefter: Well, I think you’re using the word fashion in a broader sense than couture. Or style. The thing is, yeah, you’re absolutely right. That signaled a new time.

When Dick went to Nova Scotia and photographed Robert Frank in the summer of 1975, Frank was very uninterested. He told me this. He said, you know, “Ugh, Richard Avedon came to photograph me, and I had to endure it. I didn’t really wanna do it, but okay.” And you can see that in the picture. In Dick’s portrait, Frank is so very grounded. He really couldn’t be bothered. And he’s looking at Dick with a kind of obdurate animal confidence.

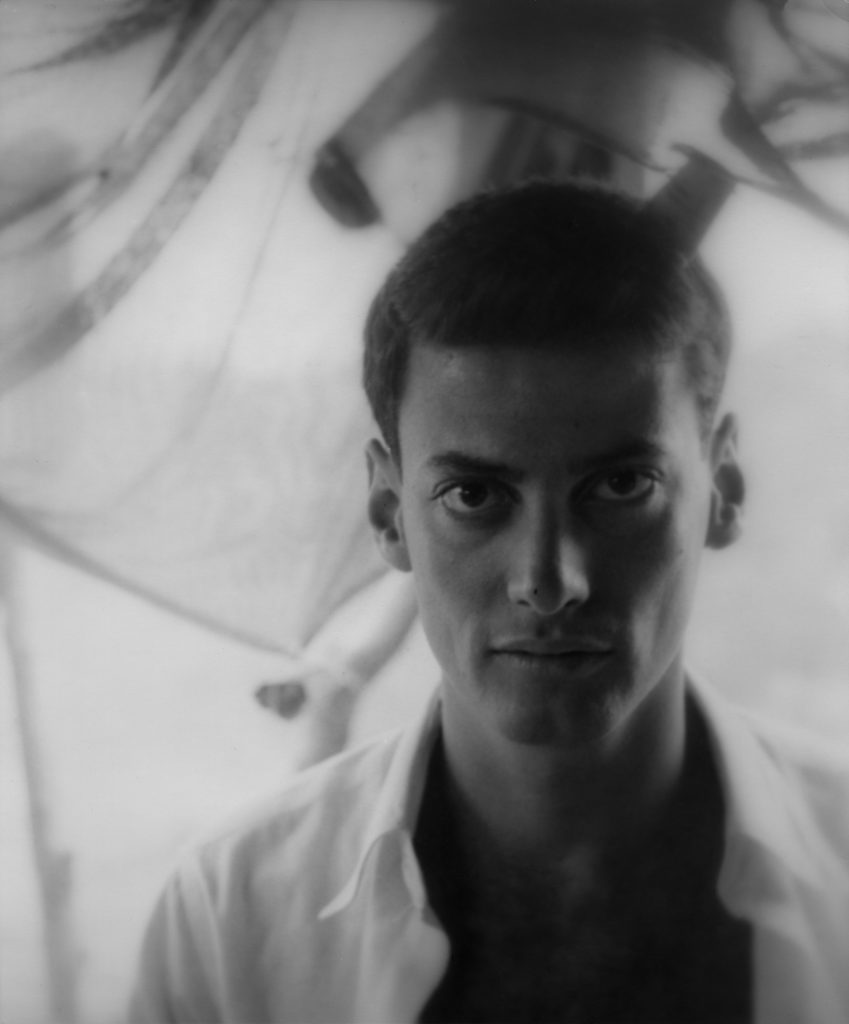

Interestingly, while Dick was in Nova Scotia, he made a unique self-portrait, I believe in immediate response to his portrait of Frank. It’s the only picture I have ever seen of Dick completely disheveled, or at least not put together in his normal urban style. His hair is kind of a mess. His shirt is unbuttoned. You can see the hair on his chest. He’s slightly unshaven. Talk about a self-portrait! I think that he was making a picture of himself trying to be as true and authentic as he believed Robert Frank to be.

Courtesy Lizzie and Eric Himmel

Wallis: Avedon is generally associated with creating a prototypical woman in his fashion photographs, yet a main part of his personal quest seems to have been to define—or obscure—his own position as a man. In some ways, the central arc of your book, which is probably also the most controversial aspect, traces Avedon’s role as a largely closeted gay man, and his coming to grips with what you call the “ickiness” of his shame about his homosexuality or his homosexual urges. Yet some people argue strongly that Avedon was not gay and never had any homosexual encounters. They point out that he was married for most of his life and had a son, et cetera. And although you paint a very nuanced picture of the rather complicated sexual dynamics of the New York cultural setting in which Avedon moved, when it comes to his own sexual life or identity, the story becomes kind of murky, relying heavily on innuendo. How do you square that?

Gefter: Well, I can square it easily. It wasn’t my intention to out him. But it became increasingly clear to me, just from my research, that he struggled with homosexual feelings.

At a certain point, Dick went into analysis to try to rid himself of those feelings. He made a choice early on that seems to me completely consistent with the culture he was living in at the time. Homosexuality, when he was coming of age—even when I was coming of age in the next generation—was like the worst taboo in our culture. You could be arrested for having sex with someone of the same sex. It could destroy your life and your career. And he was terrified of that.

Dick had a goal to live at the center of his culture, which he was able to do, in fact—the center of culture itself. And I think he made a decision tosublimate those feelings because of the general social attitudes about homosexuality. I think that as a result, he experienced bottomless shame, as many, many gay people did, and as some still do.

I think this is key to the roller coaster of his self-esteem, having these desires and feeling such shame about them, and spending a lifetime trying to keep them bottled up—trying to make them go away. He made a choice. He married Doe when he was twenty-one. And many people I spoke to who were there said that they loved each other, they had a lovely relationship, but it wasn’t really physical. It seemed more platonic. And in fact, Doe left him for another man. (Doe even told one of her sons that Dick was gay.) But because Dick wanted normalcy in his life, he then married Evelyn. And they had a child. And they lived for fifty years as Mr. and Mrs. Richard Avedon.

I don’t know what kind of sexual life he actually had. And I don’t purport to in the book. I make certain allusions, and they’re all quoted from specific people; those are suppositions. But my conclusion is that Dick just focused on his work. He was obsessed with his work. He worked all the time.

I never come out and say that he was gay. It is a very delicate subject. It’s a very personal thing. I was always trying to hew to only as much as I could verify. One thing I do have to say is that there were some revelations about his sexuality in Norma Stevens’s book [Avedon: Something Personal, 2017], which I was very careful to either corroborate or not include. The one thing I could confirm is that Dick, in his sixties, did have a clandestine relationship with a man for several years.

Wallis: This gendered, sexualized, and racialized element of cultural history is often buried or unwritten. Yet it seems to underlie your view of Avedon, and perhaps all artists and cultural producers. You mention at the very beginning of this book the triumvirate of men who you believe were responsible for elevating photography in the art world: Avedon, who you wrote about; Sam Wagstaff, who you wrote about; and John Szarkowski. So should we infer that your next biography will be about Szarkowski?

Gefter: I mean, it would seem logical. [laughs] But no. I had and have enormous respect for John, who was a serious thinker and incredibly eloquent. I have enormous respect for his writing, and also his accomplishment in establishing a kind of photographic canon. Or, at least, what used to be the canon. But no, I’m not that interested in who he was as a person.

In contrast, I was very interested in Sam Wagstaff. And I was very interested in Richard Avedon. And if we go back to this idea of Dick calling his portraits self-portraits, then in some ways, I think that the people I choose to write about reflect something about who I am.

I am very interested in what art is, and what its meaning is, and how it informs us and enlivens us, and teaches us about ourselves, and instructs us, and even tells us something about the future. And I also have this lethal attraction to glamour. [laughs] That’s just the truth. I find it completely sexual or erotic, or at least sensate. And there’s always a component of joy to that. I want to understand something about the nature of our existence. But I also love a good time.

Philip Gefter’s What Becomes a Legend Most: A Biography of Richard Avedon was published by Harper in October 2020.