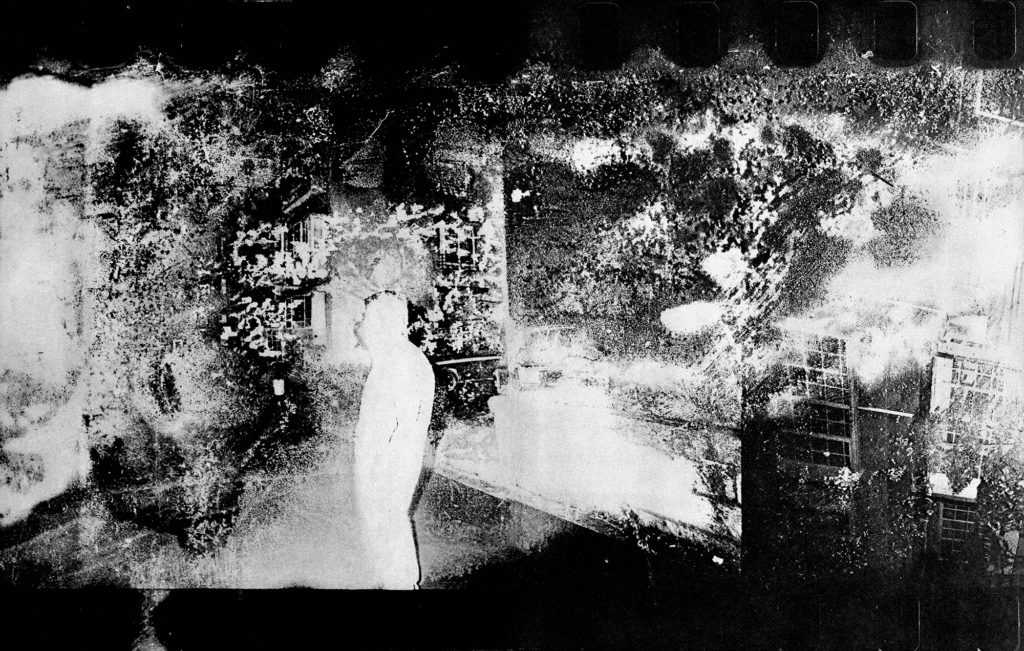

Daido Moriyama, from the series Letter to Saint-Loup, 1990

Daido Moriyama is, to a great extent, an artist both incomprehensible and misunderstood. Incomprehensible because the question he poses, What is a photograph?—besides being too far-reaching and allowing for infinite answers, all probably inconclusive—seems lost in a world ever thirstier for easily applicable definitions. Misunderstood because the labels proposed for him, such as that of a photographer who portrayed Japan in the post–World War II period, do no more than scratch the surface. Although it is seductive to view Moriyama’s dark and grainy pictures as a mirror of the American occupation of his country, his true interest lies in dissecting images down to their essence, far from social-documentary work that attempts to offer a totalizing vision of history.

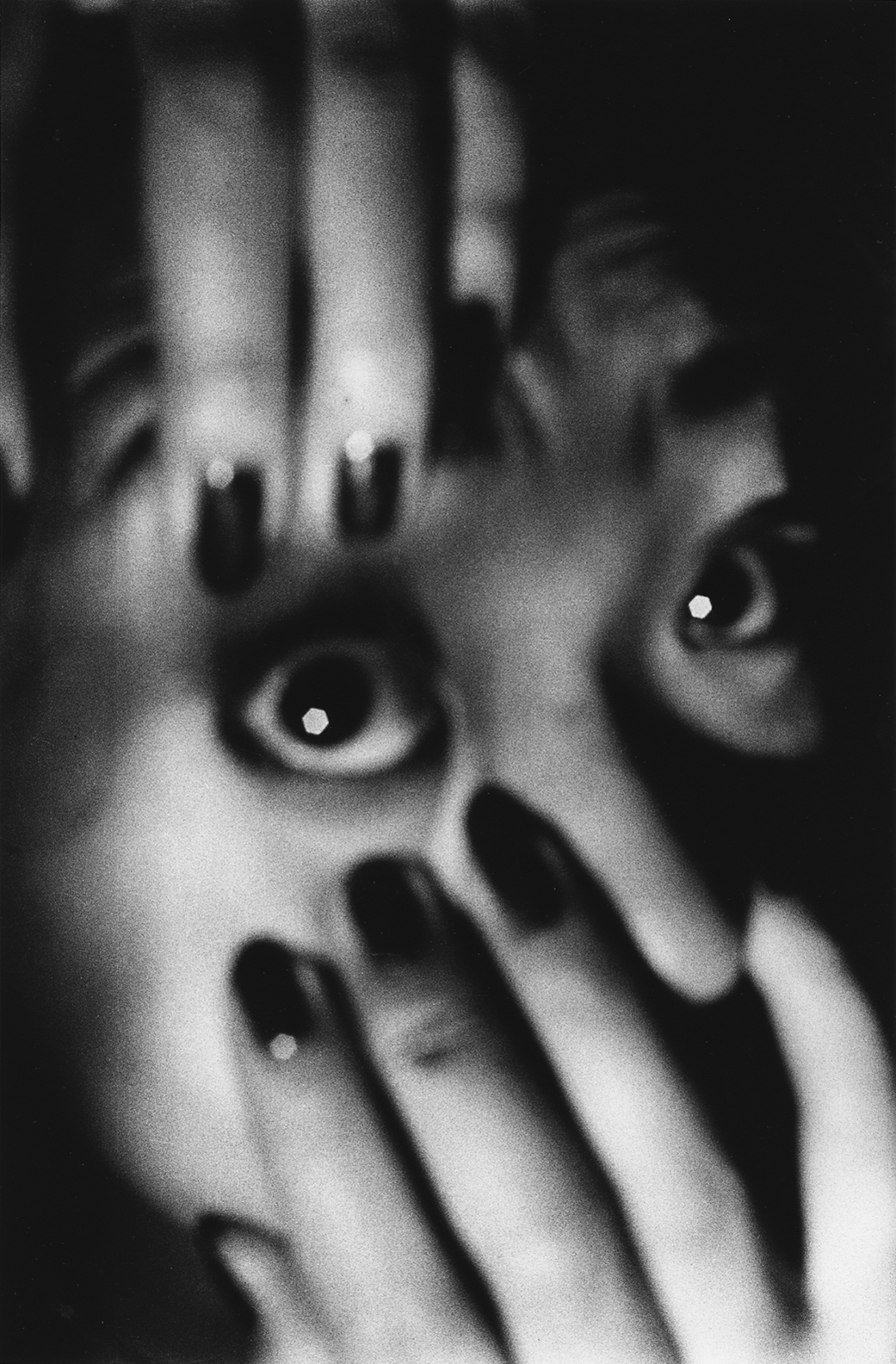

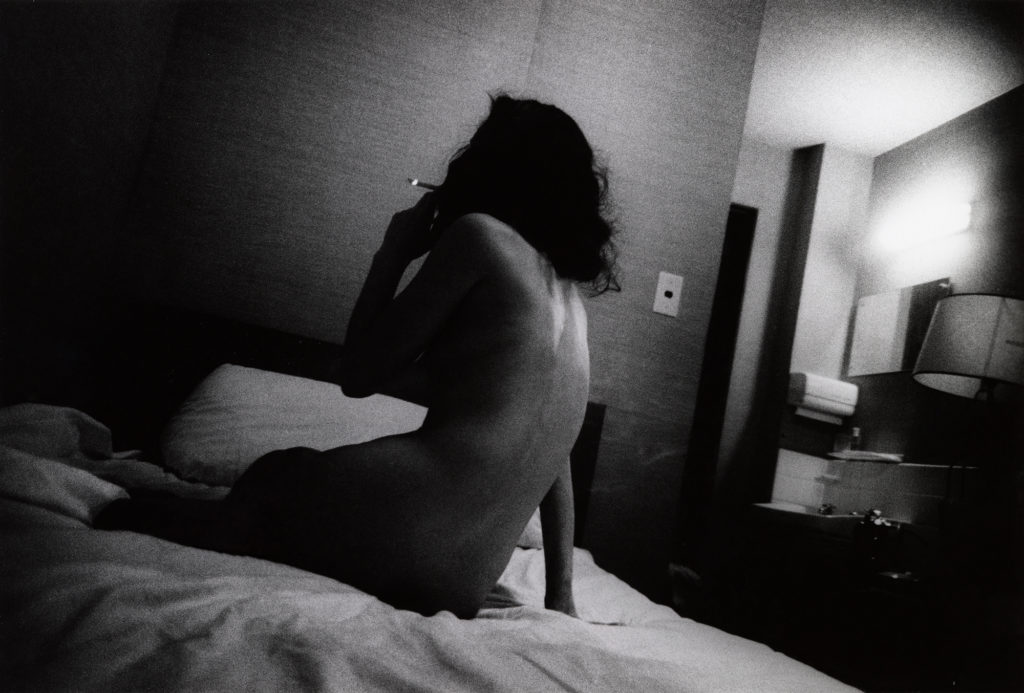

Likewise, some observers have tended to focus on the idea that his work is defined by the strong sexual component found in some of his images. This limited lens, through which many other Japanese artists are also understood, may give Western observers an easy excuse for classifying something they do not understand very well. These sexual elements are present, of course, evidenced by the photographs that have come to be seen as quintessential Moriyama, from the mesmerizing graphics of a woman’s legs in fishnet stockings to the urban scenes that crumble into the grains of a silver print. But they offer a glimpse of the artist’s vision without revealing all.

A retrospective of Moriyama’s work currently on view at the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, highlights the Japanese photographer’s conceptual thinking and reveals the seeds that led to his radical works. A centerpiece is Farewell Photography, a photobook that brings together photographs, cropped negatives, and even works of other artists. The 1972 work epitomizes the process through which Moriyama sought to totally negate authorial work and style—which, ironically, he ended up reaffirming. Images from this now iconic book cover one exhibition wall from top to bottom. Before arriving there, viewers pass works that served as Moriyama’s research for essays (he also wrote about the medium) that sought to understand how photographs are produced.

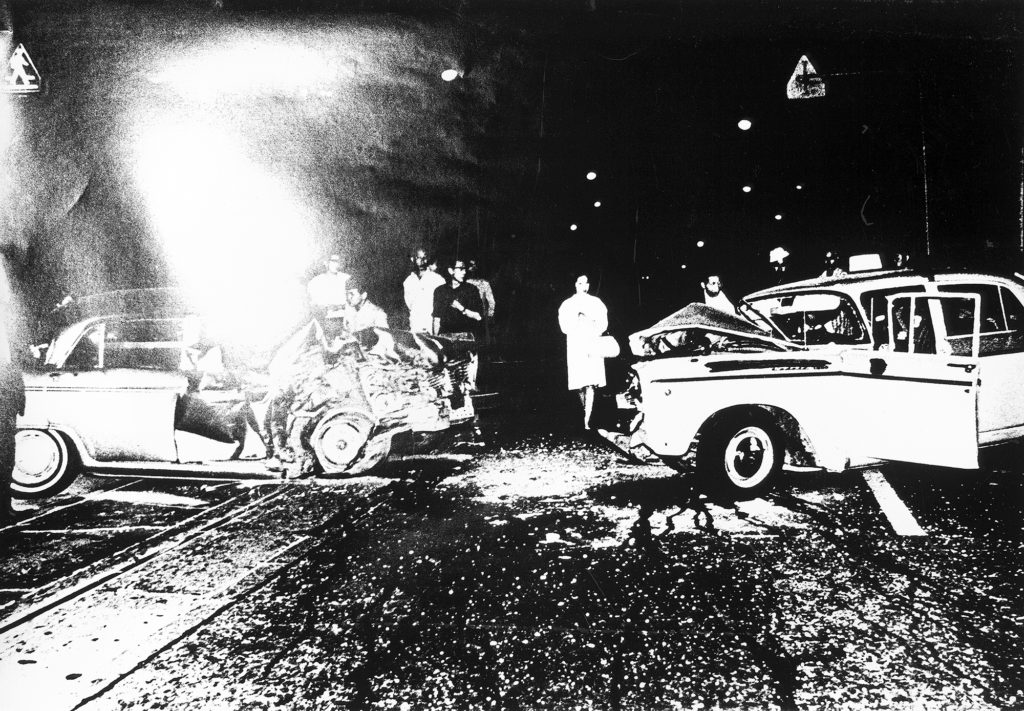

In a society already overloaded with mass media, Moriyama defied the conventions of photojournalism, publishing his radical, experimental works in a number of Japanese photography magazines of the era. He was greatly moved by images of Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination and responded by creating his own reproductions. He rephotographed images found in newspapers, magazines, and on television, publishing them in 1969 in Asahi Camera. In another series, Accident, from that year, he accompanied police to crime scenes, so he could shoot the immediate aftermath of incidents, avoiding the tendency of the press to relay something from secondary sources or outside witnesses. In both cases, he questions the role of the photographer as someone who has the power to present a summary or prepackaged view of a situation.

Moriyama’s reproduction of a Tokyo transit agency’s poster featuring a photograph of a car accident is a clear allusion to the images Warhol derived from newspaper cuttings. In this case, however, in place of the many-colored versions made by the Pop artist, Moriyama opted for heavy black and white, the result evoking a rough photocopy with the texture of a Warhol silkscreen. If photography imitates the world, a photocopy is the most radical and transgressive form of the image. The show highlights another link between the two artists with a series of images of tin cans. The fact that Moriyama shot these products on a supermarket shelf, and not isolated against the white background of a photography studio, as Warhol did, is only one of the striking differences. Again, using black and white, without the advertising approach or the stark lines of a Warhol, Moriyama traces a subtle critique of American influence in Japan in the postwar era. It is one of his rare works that openly expresses social and political critique.

Although it is seductive to view Moriyama’s dark and grainy pictures as a mirror of the American occupation of his country, his true interest lies in dissecting images down to their essence.

The exhibition’s curator, Thyago Nogueira, featured Farewell Photography on the venue’s first two floors by hanging framed pictures over wallpapered reproductions of spreads from the entire photobook. The display follows the wishes of Moriyama, who believed his photographs were made for books and magazines, not for museums. The exhibition also presents his many photobooks to be browsed through, and includes other important moments of the artist’s journey, such as the work he published in the short-lived Provoke magazine, now a landmark of Japanese photography.

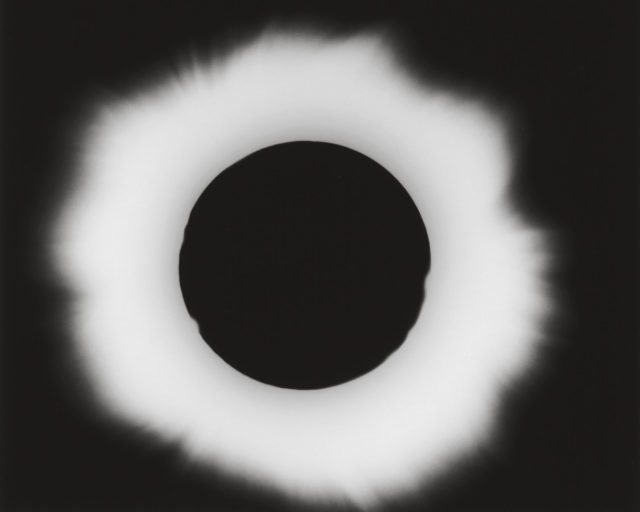

With his determination to strip photography of any pretense of explaining the world, Moriyama provokes political debate around engagement versus alienation, or what is special or banal. Farewell Photography is a radical photobook that might have been made by anyone, since at the core of the work is the elimination of the figure of the author—but, of course, that wouldn’t have been possible without Moriyama as author. The more Moriyama attempted to erase himself from the image’s interpretation, the more he strengthened the presence of an artistic thought process. Today, the aesthetic of black-and-white images, with a high level of contrast and frequently out of focus, have become synonymous with Moriyama. This black-and-white work is so forceful that a rare series of color photos included in the show appears to have been created, with a few exceptions, by some other, more conventional photographer. However, one of Moriyama’s most well-known images, of a prostitute in an alley seen from a crooked perspective, is famous as a monochromatic portrait, although it was originally produced in color.

All photographs courtesy the Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

The second part of the retrospective features works created from the 1980s onwards, after Moriyama overcame depression and resumed wandering the streets after a long hiatus, documenting everything that caught his attention. His approaches are varied, as are the objects he captures, as though he was reacting instinctively and using the camera as a notepad. This process is evident at the end of the exhibition, in a room containing three large projections that show a long, immersive sequence of more than one thousand photos made by the artist for Record magazine from 1972 to today. As in his photobooks, the accumulation of images here has power, making clear that spending hours surrounded by images left behind by Moriyama may be the best way to experience his often misunderstood vision.

Translated from the Portuguese by Clara Allain.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is on view at the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, through August 14, 2022.