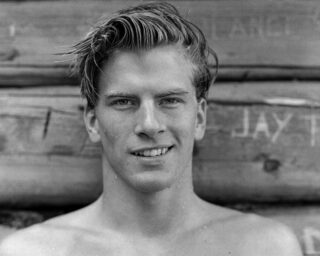

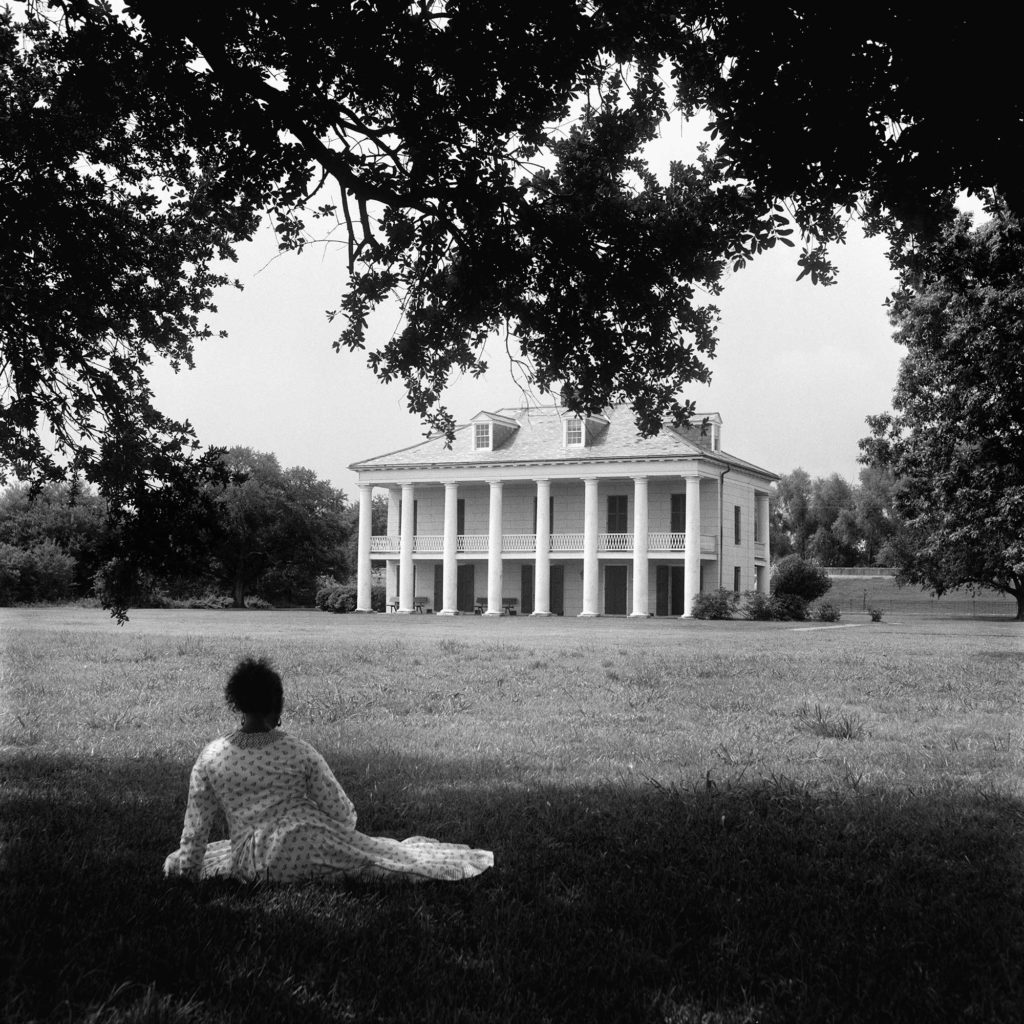

Alice Proujansky, Deborah Willis, 2017

Courtesy the artist

In 1973, Dr. Deborah Willis, then an undergraduate photography student at the Philadelphia College of Art (UArts), submitted an independent research proposal about the contributions of Black photographers to the history of American photography from 1840 to 1940. Willis had sent fifty letters to various collections and libraries, seeking information about photographers such as Gordon Parks and James Van Der Zee. “Is a photographer primarily a creative artist rather than a mere recorder?” she asked. “Could these black photographers receive the same recognition their white colleagues received?” Across her prolific career as an archivist, historian, professor, and photographer, Willis has answered these questions about recognition through her groundbreaking studies of Black photographers, her contribution to numerous photobooks, and her support over the years of artists and writers seeking to make space for an expanded, more inclusive history of the medium.

But, for all of the publishers who supported her quest enthusiastically, Willis, the guest editor of Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review, also encountered editors who clung to dated narratives about photography and race. No one said changing minds would be easy, yet Willis was determined. She would go on to win Guggenheim and MacArthur Fellowships, and become a revered professor at New York University, where she is now chair of the Department of Photography and Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts. Willis recently spoke with Brendan Embser, her former graduate student at NYU and editor of Aperture monographs on Deana Lawson and Ming Smith, about her earliest encounters with photobooks and how the photobook as a medium continues to be transformative.

Courtesy the artist

Brendan Embser: When we were launching Deana Lawson’s Aperture monograph two years ago, she gave this beautiful speech. She said she hoped that one day, a young woman would come to the library in Rochester, New York, where she grew up, and discover her book. Her vision was about sharing. That moment, which I found so moving, reminded me of you and your stories about growing up in your mother’s beauty shop in Philadelphia and sharing magazines like Jet. When it comes to photobooks, did you have an experience of going to the library or bookshop and feeling transported by a single book?

Deborah Willis: Yes, I was seven years old. It was Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life [Simon & Schuster, 1955]. We had to pick a library book every week growing up, and I just discovered that book visually. I saw it on the shelf and I took it home. I was so fascinated with the beauty of the light in the photographs. I could see that the lighting and the woman were so beautiful. The bare bulbs in the kitchen. It was intimate; it looked like love. That’s how I grew up, with my family. It was always about love.

Embser: Did you think of the book as a distinct experience visually from the magazines that you were looking at?

Willis: Then, I didn’t. But the connection for me with that book, and with magazines—Black magazines—was the experience of seeing Black people in print. We had National Geographic, which was a different way of seeing Black people, mainly in Africa. But to see Ebony magazine, and Jet, and Bronze, and Hue, and all of the magazines that my parents subscribed to—this was a part of the spectrum, the experience.

Embser: Do you remember the first photobook you ever bought for yourself?

Willis: The first photobook I bought was the catalogue to the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition Harlem on My Mind [Random House, 1968]. The second book was The Black Photographers Annual [1973–80]. That was really major for me. I was an undergraduate student, looking for a way to examine the history of Black photographers, but also trying to recognize that there was more than what I found in my photo-history books.

Embser: When you worked as an archivist at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, did the Schomburg make a point of collecting photobooks at that time?

Willis: I was conducting research at the Schomburg Center in the mid-’70s, and they didn’t collect photobooks specifically; however, there were numerous pictorials on Black life in the collection. And, there was The Black Book [Random House, 1974] by Toni Morrison, which had photographs in it. I discovered that at the Schomburg. Five years later, when I was hired to be the photo specialist and then became the photo curator there, I saw the gap. I noticed that there was something that I needed to do with organizing and creating the “bio-bibliography,” which would eventually be the first book that I did, Black Photographers 1840–1940: An Illustrated Bio-bibliography [Garland, 1985].

Embser: Were you also acquiring books and objects for the Schomburg? And did you make a point of collecting artists’ monographs, or would that have been the library’s job?

Willis: Yes, I was lucky enough to work with Ruth Ann Stewart, and with Jean Blackwell Hutson—both headed the Schomburg. Ruth was helpful in guiding me through, allowing me to create books that could be used in the archives, where photos were held, but also for the general library, which researches used.

Embser: How were you able to find publishers for your own books?

Willis: I had an angel. His name was Richard Newman and he worked at Garland Publishing, which created books on African American histories. Within a month of starting at the Schomburg, Dick called me up and asked me if I would like to do a book on Black photographers. And I said, “Well, I have an undergraduate research paper.” And he said, “Send it to me.” He told me we should create a book that was a resource list of photographers. In the end, I had over three hundred names in there. And that was the beginning—the bio-bibliography from 1840 to 1940. And it was so successful that he asked if I wanted to do another one, and I did, extending that history from 1940 to 1988.

Embser: In addition to these historical studies, you’ve also worked on artists’ monographs. Do you have a favorite from your early career?

Willis: In the early 1990s, Andy Grundberg, at the Friends of Photography in San Francisco, called me and said, “I’d like you to do a book on any photographer. Who would you like to do it on?” I said, “Lorna Simpson.” I was really excited to have that opportunity to meet with Lorna, interview her, create that book at a crucial time in both of our careers and lives. That was Lorna Simpson [Friends of Photography, 1992].

Embser: It sounds like you had key supporters at the beginning of your career. But did you get pushback too?

Willis: Sometimes, publishers battled with me and didn’t believe the history. For my book on Van Der Zee [VanDerZee: Photographer, 1886–1983, Abrams/National Portrait Gallery, 1993], I saved the letters that they sent to me, where they said I was inflating his contributions to the field.

Embser: What exactly would they say?

Willis: Here’s one: “On pages 3/4—Here I feel she inflates Van Der Zee’s achievement. Certainly, others of his time with not much more sophistication or training, accomplished similar technical results. Moreover, such earlier photographers as O. G. Reijlander (to whom she refers later on) used combined-image printing, so Van Der Zee cannot be credited with innovation here. The superlatives (‘astonishing’) need to be toned down.” Or this: “No evidence is given that Van Der Zee possessed issues of Camera Work or otherwise acquainted himself with the work of Strand, Stieglitz, and the photo secessionists. Therefore, it is dangerous to associate his work with new developments in photographic aesthetics, except insofar as it shares a spirit. The problem for me is that I do not find this shared spirit in Van Der Zee’s work . . . One of the unique and potentially most valuable aspects of Deborah’s approach to Van Der Zee’s work is that she deals with it in terms of ethnic consciousness.” [Laughs]

Embser: The word dangerous—I mean, what is that about?

Willis: I know, it’s amazing. The battles I’ve had in publishing had a lot to do with the narratives that people wanted to hold onto. Here is another: “I do not consider Van Der Zee’s photographs radical cultural intervention. Van Der Zee’s photographs didn’t change the way things were: they recorded it. What was surprising, I think, to many white viewers who grew up in a segregated world is that there is this strong, mainstream, upper-middle class tradition that has deep roots in the nineteenth century. It is more about being upper-middle class, irrespective of color.” I could go on and on.

Embser: When you look at the contemporary art world and art publishing right now, after all the work you’ve done, what do you think that publishers can do to better support Black artists and the range of visions that they have for publishing?

Willis: I think the dialogue is really important, what’s happening now. And that discussion increases when we have editors who are sensitive not only to Black photographers in the West, but also look through the lens of African photography, through Asian photography, Latinx, Native American, with a much more critical eye, and to know that there are vital books that need to be encountered.

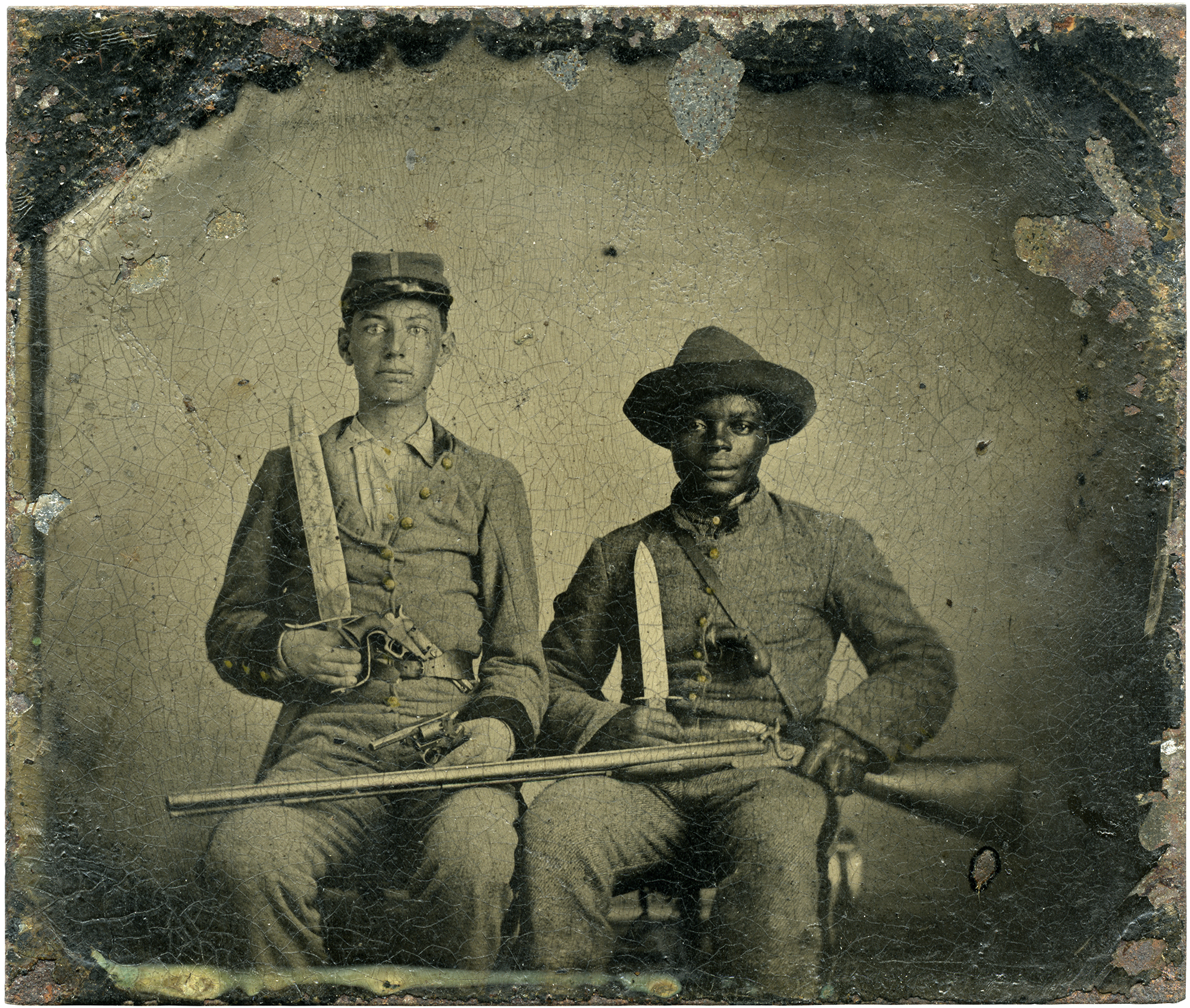

Courtesy the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, and NYU Press

Embser: Do you want to say something about your new project The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship [New York University Press, 2021]?

Willis: I’ve been working on this for the past seven years, looking at the experiences of personal memory and public memory, and how photography shaped the history of the presence of Black Civil War soldiers. I wanted to find photographs, letters, and diary pages of Black people who were teachers, preachers, women who were teachers and nurses, Black soldiers who were part of the fight for their own freedom. When I was in school, we didn’t have that discussion. We didn’t talk about Black Civil War soldiers. We didn’t know who fought. And the fact was, there was a strong history that basically was ignored.

I write that the notion of resistance and recovering stories is key to the image of Black soldiers. Cultural historian Alan Trachtenberg wrote that the role of African Americans in the struggle against slavery has been long repressed by guardians of official “privileged versions” of the American past. Racial prejudice has been the major cause of the expunging and erasure of the role of Blacks in determining their own future—and this erasure remains in the interest of some groups invested in continuing and preserving racial inequality.

I wanted to respond to the question of how Black male identity is formed through the photographic image. I found an amazing collection of images at Yale, in Boston, in DC, and here in New York. These collections are available, the photographs are there. Now, there’s an opportunity for people to see that there was a Black presence in the war.

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Embser: One last question for you. This is like a variation on the BBC Radio program Desert Island Discs. So you have three books, and you’re going off to the desert island: one for your granddaughter, Zenzi; one for your son, Hank Willis Thomas; and one for yourself. What are they?

Willis: For my granddaughter to read with her mother, Rujeko, I really love this book called My Mommy Medicine by Edwidge Danticat [2019]. It has pictures, illustrations, text. The narrative is about a child in need of comfort and assurance. I would definitely give Hank, Gordon Parks’s Collected Works: Study Edition [Steidl, 2017]. And I would take with me Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video [Yale University Press, 2012]. It has all of what I love, and it gives the opportunity of seeing, witnessing the Sea Islands, Africa, Europe, experiencing performance, but also looking at folklore and memory. I would spend my time with that on an island, encouraged to create more work, and I would just love that moment.

This piece originally was published in Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review.