William Christenberry, RaMell Ross, and the American Crucible of Hale County, Alabama

A remarkable exhibition by the two artists charts a visionary path through the landscapes of the South.

RaMell Ross, Sleepy Church, 2014

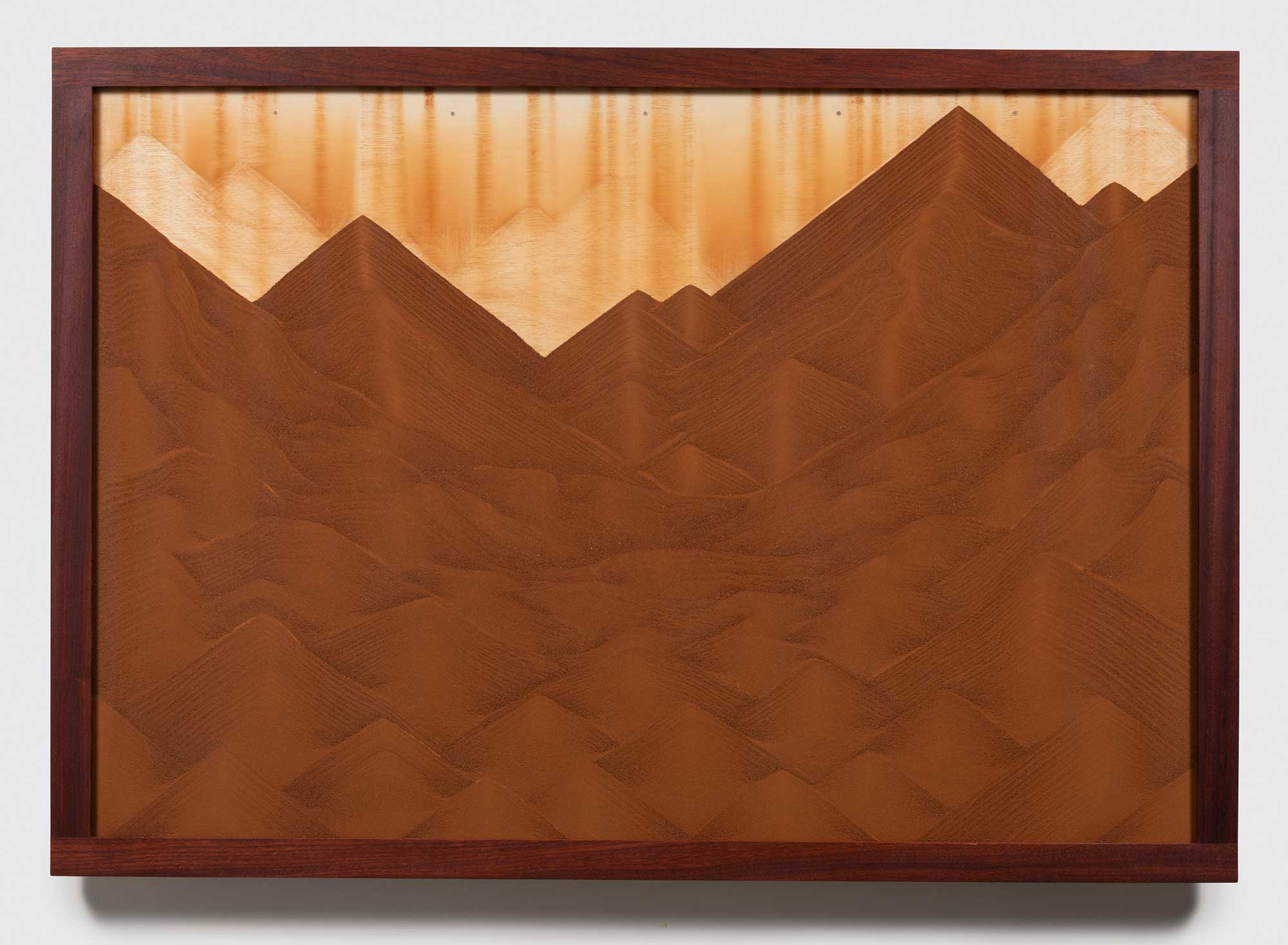

The first landmark you see is red dirt framed in wood, behind museum glass—Alabama red soil, crucially. In Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land; Altar (2021) by RaMell Ross, red dirt undulates in triangulated peaks, toward a horizon of what appears to be the roof of a house. It’s the opening work in William Christenberry & RaMell Ross: Desire Paths, an exhibition in the form of a dialogue, at Pace Gallery in New York. Desire paths, meaning those trails worn into the ground contrary to roads planned and paved. They are herding animals’ footpaths to water, they are shortcuts sometimes, or they are secret passageways, or they are escape routes, or, particularly when it comes to the impressions left behind by human footprints, they are often driven by some less practical, enigmatic impulse.

Around a corner, that same dirt appears in the base of a sculpture of a barn painted green, by William Christenberry. “You don’t call it dirt, son!” Christenberry recalled in a 2005 Smithsonian lecture, quoting the redressing he’d once received from an Alabama agronomist uncle. “It’s soil! Soil nurtures life!” But soil, he lamented, inevitably came out as soyl in his Tuscaloosa-born accent. He’d eventually adopt the word earth to describe the substance that he’d carry back to his home in Washington, DC. “He would bring home boxes and boxes of red earth, and he had a screen that he made, so he would take it out in the back yard and sift it,” Sandra Deane Christenberry, his wife, told the New York Times in January.

That red earth rises to meet the countenance and consciousness of a Shel Silverstein drawing—Ross’s appropriation of the cover illustration of A Light in the Attic, featuring a kid with a house sprouting straight from his head, framed under glass surrounded by more Hale County dirt. Ross fills in the space of the line drawing with brown crayon, giving color to the child’s skin; the house and its pointed, triangular roof are left paper-white. Ross, a photographer, artist, writer, and filmmaker whose childhood geography followed the paths of a military family’s relocations, lives both in Rhode Island, where he teaches at Brown University and, since 2009, in Hale County. Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018), his transcendent and acclaimed essay-film, was nominated for an Academy Award in 2019.

Despite being artistically anchored in the same place, Ross and Christenberry, who died in 2016, did not meet in life. But they converse meaningfully, powerfully, in this group of selected works: paths that crisscross, overlap, double up, converge and diverge. It feels less like an exhibition than a spiritual dimension—a Hale County of the mind—and also a real and actual physical place: a forest in which the people of Ross’s photographs move across time, finding their own place among Christenberry’s dream buildings and monuments, barns and slowly transforming buildings, among trees, and among churches. There seem to be as many of those per capita—as those of us who are from these places can attest—in a rural Southern town. Mining, digging, moving through, replanting, Ross and Christenberry are working with the same dirt, that red earth.

Two more works by Ross hold more red dirt inside containers for memorial flags, but the triangular shape of the frames makes them appear as if they’d been plucked out of a pasture of pyramids. They are signposts along a trail that passes by Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama (1974–2004), twenty 4-by-5-inch pigment prints that Christenberry made over the course of three decades—some of the small, square, serial photographs for which he’s best known and often misunderstood. Even before his good friend William Eggleston turned to color, Christenberry had begun photographing with a Brownie camera he received as a Christmas present in his teens, processing the film at drugstores. A visual artist whose first love was drawing, he initially didn’t think very seriously of the photos.

In 1961, during a year of mostly odd jobs in New York, Christenberry showed his paintings to Walker Evans, whose own Hale County project Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) was known then to Christenberry though it had not yet become the prevailing portrayal of his home region. It was Christenberry’s drugstore photos that Evans, who’d hired the young Alabama artist to file photos at Fortune, was most taken with. “Your camera is like an extension of your eye,” Christenberry later recalled Evans saying. Though he didn’t last long in New York, Evans’s encouragement was enough to propel Christenberry toward Hale County, a place to which he would return annually, from Memphis or Washington, DC, to photograph, over and over, the same places and things. Including this red barn and an old warehouse, with its impossibly verdant, practically fertilized shade of green.

Perhaps you have misread Christenberry before, as simply another photographer of old barns and rural gas stations and general stores and Southern landscapes, subject matter that dares to brush up against sentimentality. And yet his small pictures, approached in a style influenced by Evans (“a severe frontality,” as Christenberry described it), only appear at first to be objective—they demand a closer, longer look to perceive the subjective and conceptual undertones at play. “I don’t want to evoke nostalgia but deep, profound feeling about these little structures,” he once said, meaning both his pictures and the sculptures of them he also made, and the works that would come to him through the subconscious.

In truth, Christenberry’s photographs don’t want to show or preserve the little old house as it once was, but to reveal its changes over time, to suggest the impressions of humans without actually depicting any people. The eventual appearance of a prefab gray shed in front of the red barn—tacked with a hand-painted sign reading Vote Here. Christenberry was drawn to the folk expression of a graveside cross made of egg cartons; he loved and collected vernacular signage as object and as omen, whether the benign, the accidentally suggestive (a roadside sign featuring a particularly phallic ear of corn adorned one of his early book covers), and the rural mystic. PALMIST reads the sign of a local reader and fortune teller, its puffy painted hand waving an upside-down hello from a dusty window. (The Underground Club, a similar series not included in this exhibition, witnesses the rise and fall of a country store over decades, eventually resurrected as a nightclub—perhaps following its own desire path.) Returning yearly without wandering inside enhances the buildings’ unknowability: What might have occurred within these places? Who might have met within them? What darker secrets might they hold? “I had a desire, as I say, to come to grips with that landscape in which I grew up, the positive and negative, the dark and the light,” Christenberry said.

In 2009, Ross left Washington, DC, to work as a teacher and a basketball coach in Hale County, where he found himself pulled into the place, entranced by its “haptic lull,” as he wrote in a 2015 essay. His first three years there, without making photographs or filming, translated into a longitudinal perception and a desire to free the people in his eventual pictures, especially the city’s Black residents, from the framework of imagery. “I wondered in a daydream’s light how to unburden the African-American body and skin,” he wrote. “The problem of representation had become a conceptual challenge. I wanted to engage the photographic narrative of the historic South, but provide its representation some breathing room and loosen the hold of iconic meaning.”

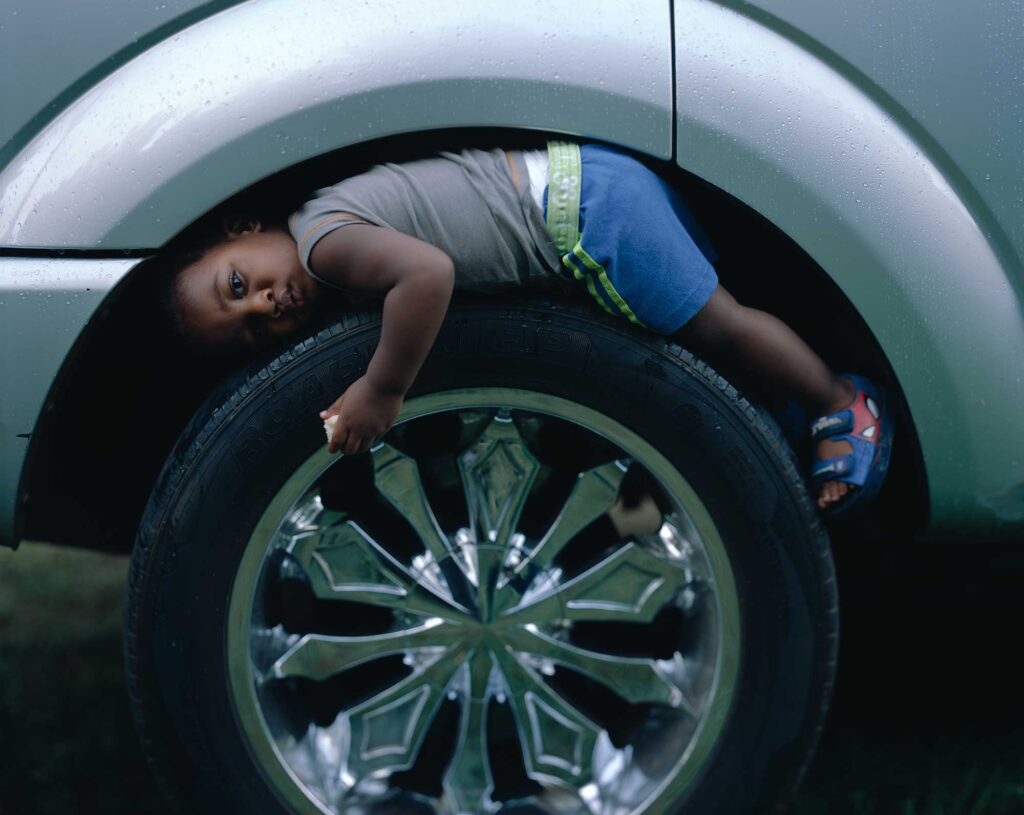

The people in Ross’s photographs are often seen in the midst of doing everyday things within deep time, in the midst of a larger landscape, so that the prosaic becomes almost mythic.

The people in Ross’s photographs are often seen in the midst of doing everyday things within deep time, in the midst of a larger landscape, so that the prosaic becomes almost mythic—whether simply sitting, overlooking a field, maybe on a break (Gahhh Damn, 2022), or a young girl kneeling, absorbed in a flowering plant (Yellow, 2013), a man carrying long lengths of pipe through a forest (Koo-See Mountain, 2019). Even Man (2019), a photograph of a boy exploring the underside of a car, curling himself in the space between body, chassis, and tire, is endowed with a dreamlike languor. It was a moment, Ross has said, that occurred naturally, one he noticed in the midst of an afternoon hanging out in a friend’s yard; like many of his photographs, Man emerges from familiarity and stillness, an awareness of time that allows the people in them to be seen whole, rather than assessed in a decisive instant. His pictures quietly overturn the historic violence of photography and the language that describes its mechanics: capture, frame, shoot, take.

In most interviews and lectures he gave in his lifetime, Christenberry has recounted the encounter in the 1960s when, as a young art professor still living in Alabama, he had a run-in, alone, with a fully hooded Klansman in an upstairs room in a courthouse in Tuscaloosa. He fled in terror. A couple weeks later, while sleeping, he had a vision of his first “dream building.” The Dream Buildings, several of which are in this exhibition, with deeply pitched, evocative white roofs, are coated in a white glue, a material that Christenberry equated with memory. When an assemblage of red earth, a long, thin wooden stick, and gourds converge in Dream Building (“Strange Fruit—in Memory of Billie Holiday) (2004), it feels also like an homage to Magritte (Christenberry acknowledged the influence of the Surrealists). Think of the Dream Buildings as extensions of the photographs, or as expressions of perception and the subconscious. In an essay in the Summer 1989 issue of Aperture, “Memory Palaces,” Christenberry says, “I would like the viewer to imagine him or herself on a back country road at night; you would come around a curve and suddenly before your headlights you would hit an object—almost as if in a dream.”

Toward the back of gallery there is another structure, life-size and preceded by a grave warning on a placard: viewer beware. Desire Paths marks the first time Christenberry’s Klan Room Tableau (1962–2007), has been shown in a gallery setting; it has only rarely been exhibited in museums. Like a closet, an annex, or a hidden corner inside a garage, a basement, an attic, a barn—the Klan Room Tableau is separated from the white-walled, well-lit space of the gallery. It’s dark and crowded in there, claustrophobic, crowded with four hundred drawings, sculptures, photographs, paintings. You may feel as if you are stumbling into some evil subconsciousness, as if you are discovering the manifestation of someone’s sinister desires.

© Estate of William Christenberry and courtesy Pace Gallery

Unlike Philip Guston, with his gleeful, satirically cartoonish Klan figures, Christenberry, for the most part, constructed faithful representations of actual iconography and costumes of the KKK. In accumulation, they are impossible to dismiss as an isolated instance or an aberration, but are joined to an entire story of terror that extends beyond Alabama and the South. “What I want to do is make people look at evil,” the artist once said. There are the satin Klan costumes Christenberry made by hand, placed on dolls—GI Joe figures and reversible rag dolls, little cloth girls who, flipped over, are dressed in white hoods. There are Christenberry’s photographs of the costumed dolls. A white neon cross. A drawing of a hooded man, who seems to match Christenberry’s description of the faceless figure that struck him with revulsion in the city building in Alabama in the 1960s, looking back at him silently through the eyeholes sliced into its white hood. Christenberry’s tableau is haunted by that encounter, compelling him to engage with his own whiteness and the closeness of white supremacy—perhaps motivated, as Ross has written, by the “fear of the terrific reflection of a potential self.”

“I feel as an artist, you can’t just back away,” Christenberry wrote in Aperture‘s Winter 1983 issue. In 1979, sixty-four pieces from the tableau—representing years of work—were stolen from Christenberry’s studio in a theft that went unsolved. Regardless of the overwhelming trauma of violation and loss, regardless of his fears for the safety of his family, he resumed the project. As you exit the room through a curtained doorway, it might dawn on you that Christenberry must have been as haunted by his nightmares as he was driven by his dreams.

Back in the wider gallery, enter into escape. In 1849, the abolitionist Henry Box Brown traveled to freedom inside a wooden box, shipping himself from Virginia to Philadelphia on a trip by railroad, steamboat, wagon, and ferry. In 2021, Ross made a reverse migration, shipping himself in a four-by-eight wooden crate from Rhode Island to Hale County. You encounter this box just outside the Klan tableau; one side is stamped DRY GOODS, and on top, “Hale County, AL This side up with care”: instruction and guide. Drop to the gallery floor to get a full sense of the dimensions of that space, its bag of supplies, shelf of water bottles for the fifty-nine-hour journey, its confines, the impressions Ross left behind (he brought along a dictionary he’s owned since childhood and copied its entries in black marker, prefacing each term with the word black, filling his interior space with a revised vocabulary: “black aberration . . . black abet . . . black abloom . . . black abluted: washed clean”). A video excerpt, playing on a wall behind the crate, documents this work and multiple vantages of Ross’s passage—the artist inking the walls, and a look like happiness evident as the crate is finally delivered, opened, and Ross releases himself in Hale County, where he’s received by a friend.

Desire paths converge. But the physical layout at Pace insists that you wind back through everything you’ve encountered before you can leave for good. Like emerging from a dark theater back into the world, eyes adjusting to the light, you are bound to see things differently. Walk among the trees and woods and painted buildings, past Christenberry’s tall churchy monuments and dream buildings, and Ross’s toppled steeple in a parking lot (Sleepy Church, 2014), conscious that you are slipping in and out of the past sixty years. Notice how, for instance, even when they do not include actual people, Ross’s photographs bear their impressions, footprints, tracks, whorls in the soil, winglike shapes left behind on the snowless red earth, the dirt angels of Hale’s Angels (2022). The is the red earth Christenberry sifted through; this is red earth rewritten.

You are bound to recognize your own dirt. Seeing Ross’s TypeFace (2021)—a lush field of wild green plants just above a vast bank of red dirt, whose face is engraved with indentations by construction vehicles, like a neat row of sentences—you flash on your own red-soil memory, seen through a flutter of sheer curtains across a gravel road. It’s hundreds of miles from Hale County, but nearly that same red, a bare-faced dirt bank grooved by rain and marked with footprints like phrases, the paths you made. It leads to a pasture of cattle, a hot-wire fence, the woods, a place where you once built pretend houses and invented made-up games in the middle of nowhere. The dirt was where you came from. The dirt was the past you held and the present you walked through. You sift it in your hands, you make your stamp. The dirt is imagination. The dirt is the future.

William Christenberry & RaMell Ross: Desire Paths is on view at Pace Gallery, New York, through February 25, 2023.