In London, an Exhibition Provokes Questions about Masculinity

In January, when invitations went out for the opening of the exhibition Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at London’s Barbican Art Gallery, one invitee emailed the show’s curator, Alona Pardo, to ask, “Do men really need liberating?” It’s a question that has, in recent weeks, become all the more compelling. “In one way, no, of course they don’t, because they hold the power,” Pardo told me recently. “But on the other hand, they do, because that power is incredibly constricting.”

There have been many exhibitions about men. And as the Guerrilla Girls have succinctly argued, the history of museums and their collections is, by and large, the history of men. But such exhibitions were usually not about “men as men”—they were about their brushstrokes, their visions, their camera work, the magnificence of their talent. The Masculinities exhibition, which reopened to the public on July 13, and accompanying catalogue are about “men as men.” The project, which includes fifty-five artists and work dating from the 1960s onward, considers, to quote Pardo and Jane Allison (the Barbican’s head of visual arts) in the catalogue’s foreword, “the ways in which masculinity is variously experienced, performed, coded and socially constructed.”

© the artist and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London

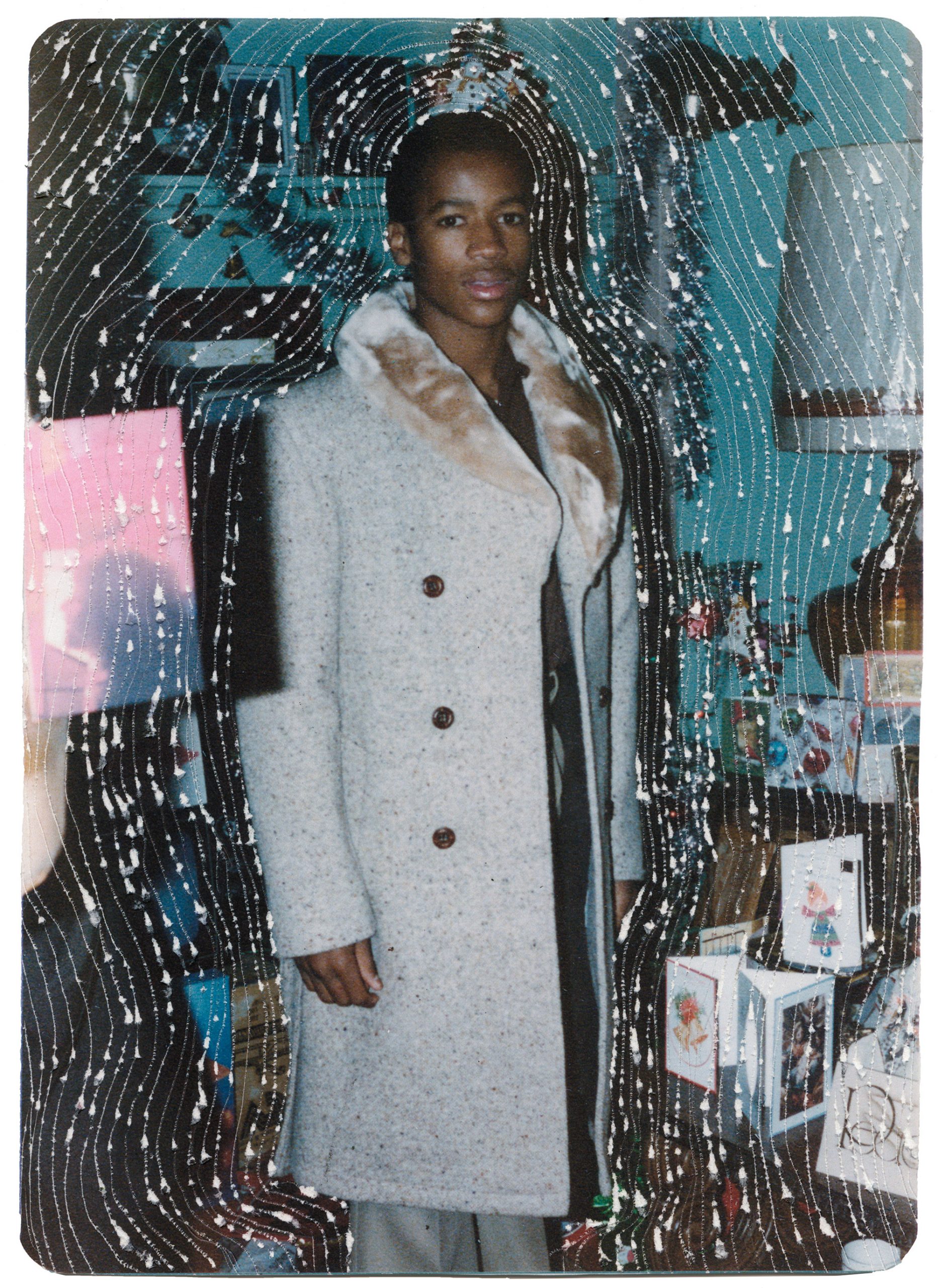

Masculinities brings together names one would predict given such a topic—Wolfgang Tillmans, Hal Fischer, Adi Nes, Robert Mapplethorpe—alongside less expected (and thus often more rousing) works by the likes of Liz Johnson Artur, Kalen Na’il Roach, and Aneta Bartos. There is a significant amount of conceptually driven photography—“performative work” as Pardo puts it—which makes sense given that this is an exhibition of the Judith Butler school of thinking: gender is socially constructed and, by default, masculinity and femininity are learned, and performed, behaviors.

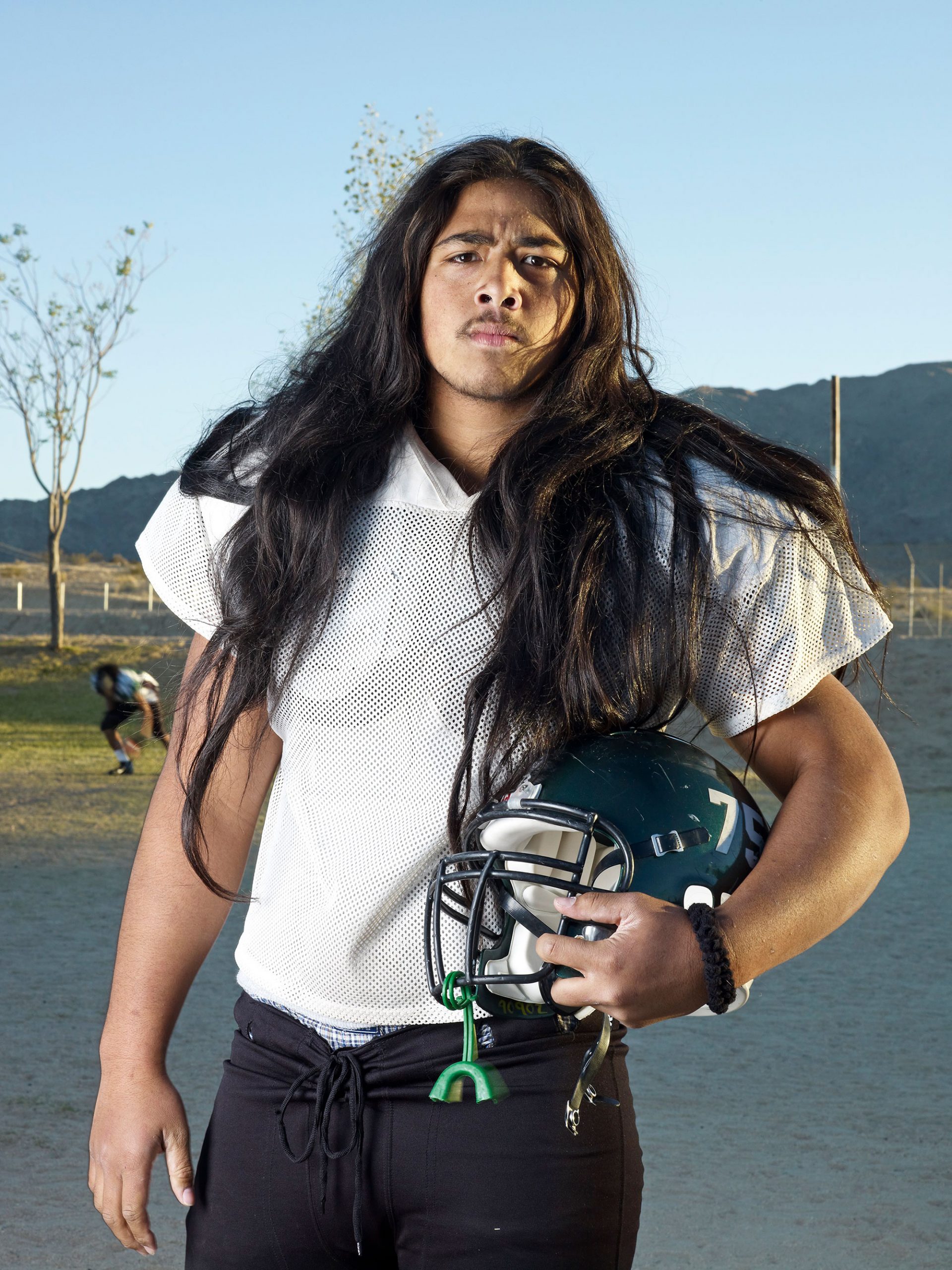

The notion of “men as men” is borrowed from the sociologist Michael Kimmel, who observed that there are thousands of books about adventures, travels, and battles, “but books about men are not books about men as men.” Chris Haywood, reader in critical masculinity studies at Newcastle University, UK, cites Kimmel in his catalogue essay looking at popular discourse around masculinity. Haywood argues that the very act of looking at men undermines notions of masculinity because, conventionally, it is “dependent on its being natural, effortless and normal.” Indeed, it seems that to be a man is to try at everything—building one’s body, excelling at work, earning more money—without ever admitting one is actually trying to become more of a man, in an attempt to bolster some shared sense of self-importance, a standard to keep up. To browse the photography in Masculinities and regard that effort, to see men as objects, flawed, constructed, fragile—in other words, to regard them in the way we often regard women—can feel pleasurable, or elicit an odd sense of vindication. One can revel in repulsion at the almost lazy bravado of some frat boy captured by Richard Mosse, or a high-school football player by Catherine Opie. Or one can feel more tender, if so inclined, when encountering a young dreamer in the self-portraits of Samuel Fosso.

© the artist and courtesy Autograph, London

Masculinity has long been omnipresent yet strangely invisible. In 1997, Sally Johnson observed that “it is precisely men’s status as ‘ungendered representatives of humanity’ that is the key to patriarchy.” And yet, right now, it is widely advocated that “good” masculinity is rooted in self-awareness which, of course, means that some men (though not nearly enough) are reflecting on gender in relation to themselves, rather than seeing it as some exterior, foreign thing that affects women or queer people.

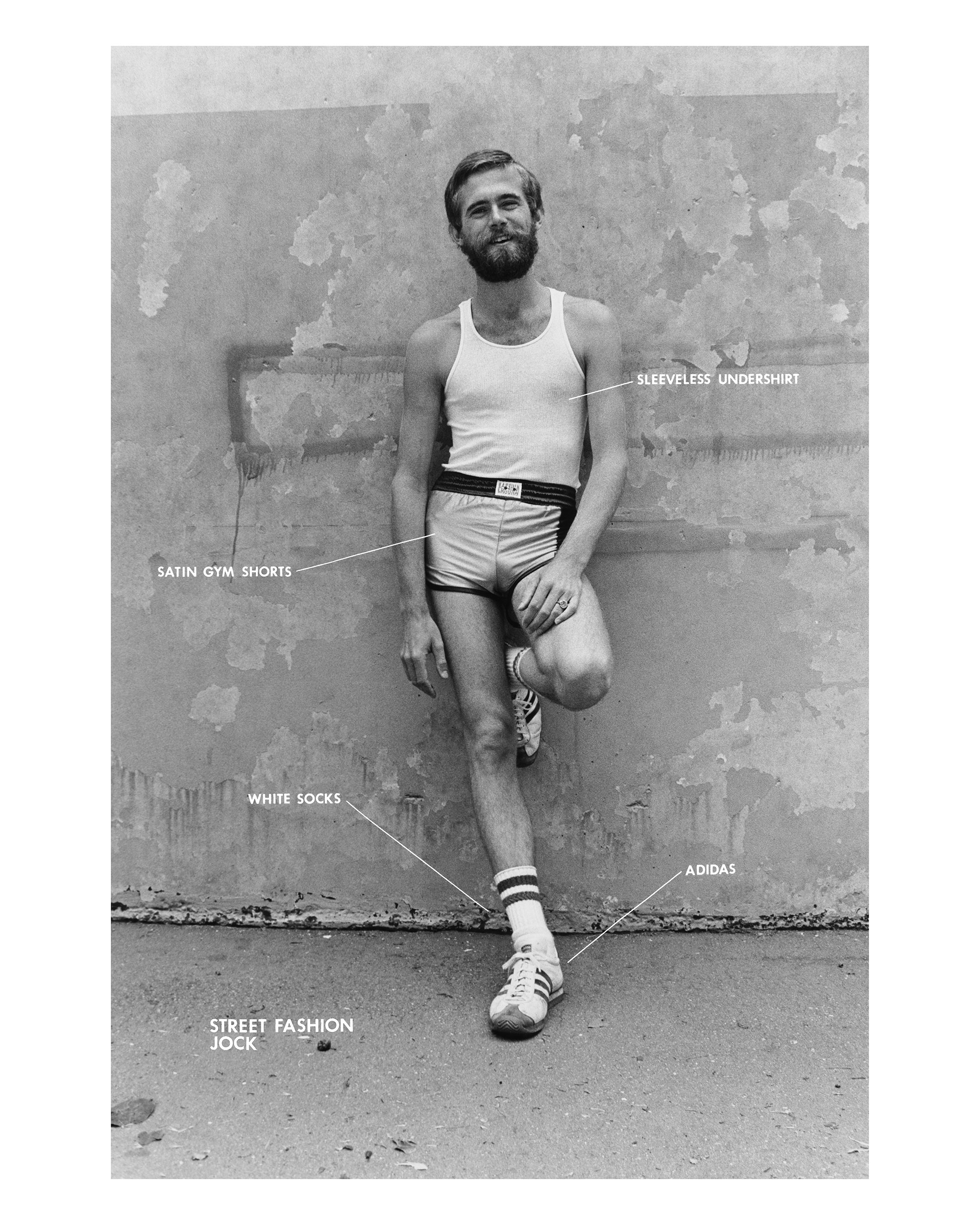

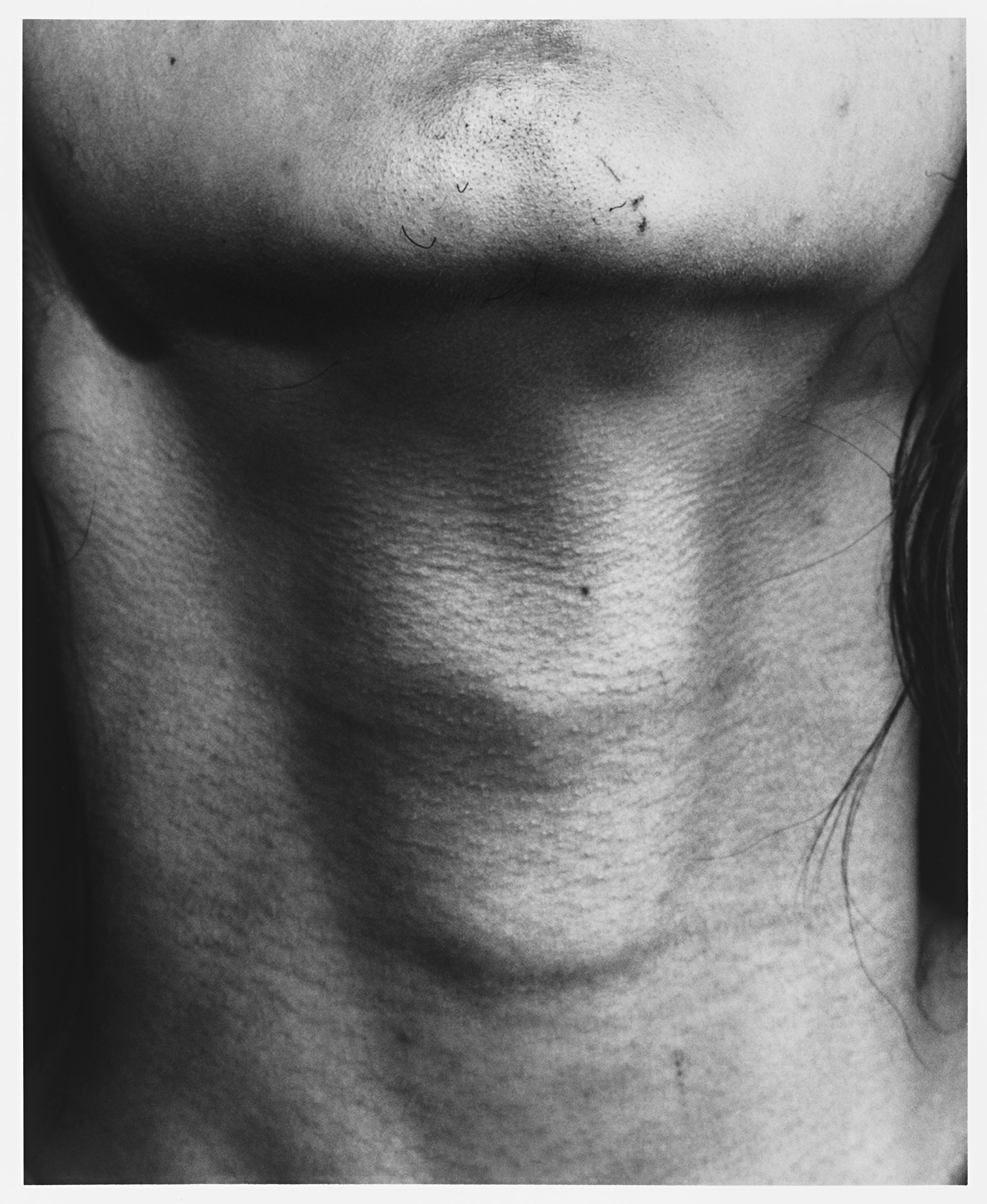

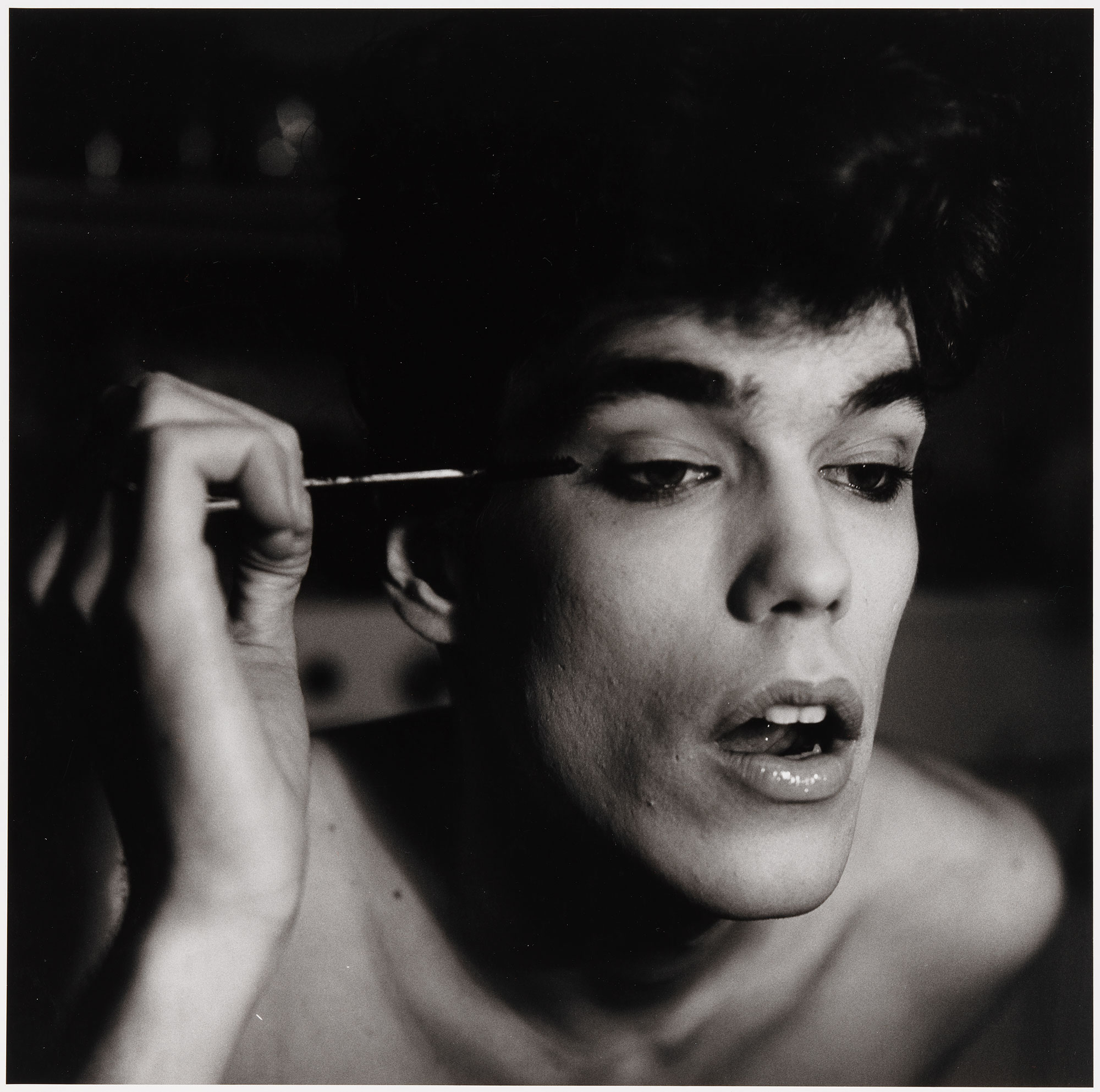

“It is a newfound phenomenon that men are looking at themselves, and men, for the first time, properly. Really examining forensically,” Pardo said. She also does some of the work for these men by considering the influence of campus traditions, the military, and sports on masculinity (although a broader analysis of the influence of capitalism would have been useful). Some photographers have done this for a long time—Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, Herb Ritz, Rotimi Fani-Kayode—but such work was seen as a fringe endeavor, or some kind of homoerotic play: “not noble, not masculine,” as Pardo puts it. In photography, gender is primarily treated—and, in turn, viewed—superficially, as a matter of appearance. Masculinities is frequently concerned with style, fashion, uniform, facial hair, and fitness. Mapplethorpe’s 1980 images of bodybuilder Lisa Lyon—toned, muscular, and thus clearly included because she looks somehow “like a man”—highlight the way that the exhibition’s agenda returns intuitively to the archetype, to the clichés of hegemonic masculinity (strength, fitness, control) as a starting point, all while trying to push against them.

Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant, London

Pardo takes as a given that masculinity is in “crisis,” although the extent to which that crisis is recognized, beyond certain “bubbles,” as she calls them, is up for debate. Look at President Trump and the attendees at his campaign rallies, clapping along at brutishness and bullying. Or the rise of “incel” groups. Or the boom in revenge porn. Or the spread of domestic violence during COVID-19 lockdowns. Or the frequency of male suicide. Or so much more. The bubbles Pardo mentions are not utopias, but instead sites of hypocrisy and self-delusion, as much as progress.

One can be aware of a problem while also unable to feel it, to turn empathy into personal action. A “woke” millennial man tweets about feminism but then ghosts his Tinder dates. Almost any woman you speak to will say that she, or one of her friends, has been sexually assaulted or harassed, and yet no man will admit that their social circle is full of creeps and rapists. “I really didn’t want the show to be men-bashing,” Pardo said. Why not? For some men, masculinity is a habit, performed with a mindless rhythm; for others, it’s an addiction, damaging but alluring, the promise of access to some higher place, some new sensation of power and control and possibility.

Courtesy the artist and Praz-Delavallade Paris, Los Angeles

The book is organized into sections which consider, first, Male Order: Power, Patriarchy and Space; followed by Too Close to Home: Family and Fatherhood. Next come Queering Masculinity, Reclaiming the Black Body, and Women on Men: Reversing the Male Gaze—an order that neatly seems to parody our broader, problematic social hierarchy, headed, as this book observes, by the cis white male. “And while it is safe to say that numerous masculinities exist within every culture and that they often vary according to class, race, ethnicity, sexuality and religion,” Pardo writes in the book’s opening essay, “it should be noted here that hegemonic masculinity sits atop this gendered social hierarchy by embodying the culturally idealised definition of masculinity, constructed as both oppositional and superior to femininity.”

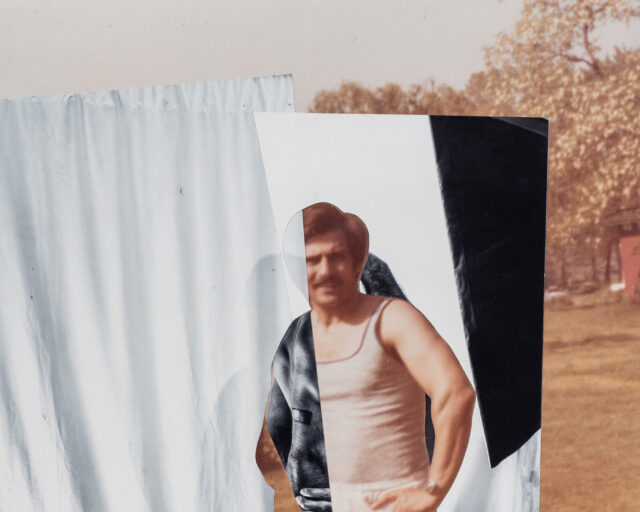

And yet, it seems that the intentions of the ordering are sincere rather than goading. It is something of a shame to see these latter areas othered away from the earlier chapters on power, space, and family—notions relevant to understanding queer culture and its representation, or Black life, and, of course, women’s art. Still, the study of gender is full of divisions, generalizations, conceptual confusions, and, increasingly, angst. It is easy to dismiss any attempt to contribute to the conversation as having missed the mark, given the way the topic intersects the public and private; the obvious and obscure; the legal, bureaucratic, and structural with the all-important individual lived experience. Masculinities grapples with all this as earnestly as any institution can, especially when dealing with a medium (photography) that has its own baggage of patriarchy, exclusion, cliché, and erasure—themes that run through the work of some of the artists featured, from the exquisite portraits of Deana Lawson to the layered work of Sam Contis. The latter’s Deep Springs series (2017), an exploration of the American West and the relationship between its enduring motifs and masculinity, is a highlight of the book.

© the artist

Perhaps because the US is currently in the run-up to a presidential election, I found myself especially entranced by Richard Avedon’s project The Family, originally made for Rolling Stone in the bicentennial election year of 1976 and featuring, among other influential figures, Ronald Reagan, who had just lost his bid for the Republican nomination to incumbent President Gerald Ford. Reagan looms large in the exhibition as a whole, an emblem for a Hollywood-cowboy kind of masculinity that presents itself as the embodiment of dignity, strength, and righteousness, an identity Reagan manipulated—as others do today. Reagan is cited by Larry Sultan, in the context of his adored series Pictures from Home (1992): “These were the Reagan years, when the image and the institution of the family were being used as an inspirational symbol by resurgent conservatives. I wanted to puncture this mythology of the family and to show what happens when we are driven by images of success.”

© the artist

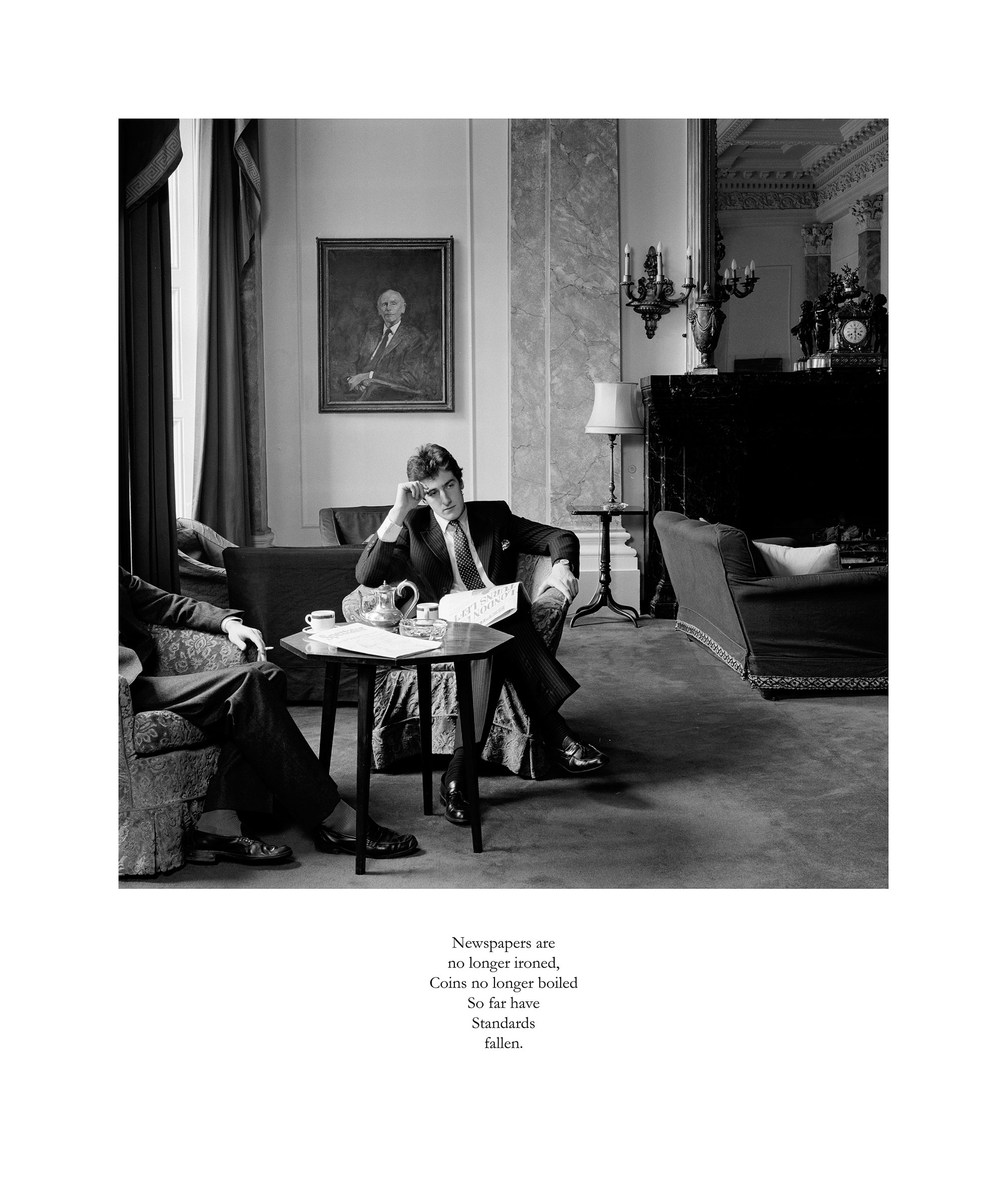

In Avedon’s series, we see bankers, executives, publishers—the network that, through a well-oiled cycle of backstabbing and propping up, shapes America’s highest office. It is one of the most convincing attempts in the book at capturing not the surface nature of masculinity, but its goals, the insidious way it pulls individuals into its cause. Such themes preempt the ideas explored in Karen Knorr’s series Gentlemen (1981–83), a study of the British political class, and Andrew Moisey’s book The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual (2018) which, to Pardo, show the “structures and scaffolding” that prop up patriarchy and “the way it is handed like a baton, from one generation to the next.” Avedon’s photographs are formal, still portraits, but you imagine the way the subjects made their way to the session, and the way they left. The cufflinks jangling as a hand is extended to shake. The woody smell of cologne. The straightening of the tie. The agreement, over lunch at the club, that the son of a friend will be given a coveted position. The box of cigars in the study. The wives in the other room while the men talk. The firmness of a hand on a woman’s lower back as it ushers her through the door. The discreet call to a lawyer to “make this whole thing go away.”

Much has changed since Avedon’s and Knorr’s pictures were made. A turning point, of course, was #MeToo, which is cited repeatedly throughout the book. Pardo said that while she had been thinking about the exhibition for years, the events of 2017 certainly “galvanized it.” This is just as I see it, but to me, the greatest shift post-#MeToo is that men now see what it is to spend each day afraid—something women have always known. We spend our time hyperaware of what others may read into our movements, our actions. What they may take from us, whether or not we want to give it. We women, through habit and pressure, turn ourselves into malleable vessels, ready to expand or retract or streamline depending on how we are treated. We are told to worry about being hurt or raped or killed with the kind of pragmatism of someone giving road directions: “Don’t walk that way at night.” Men, who once thought their actions, their dominance would never be challenged, now know that daily fear. It’s not identical—they are not afraid of being injured, but they are afraid of being shamed, accused, outed. Such fear stings.

© The Peter Hujar Archive LLC, and courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

So maybe that’s why, when reading the book, I found myself returning to the fearful gazes. I found them poignant in the images purportedly partly about strength—could the subjects sense that their power was crumbling around them? The vulnerability in the eyes of Rineke Dijkstra’s bullfighters. The pathetic bile of Anna Fox’s father’s words, screamed at her mother, and perfectly, awfully, transcribed by the artist alongside photographs of mundane props of domesticity in her series My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words (1999). The tight way a frail father grips his son, the photographer Masahisa Fukase, in the series Memories of Father (1971–90). There are various projects in the book in which a male image-maker captures his father. Aren’t all of these largely centered on fear? An exercise in grappling with, and pre-empting, the particulars of one’s own forthcoming demise?

In another essay in the book, on the subject of order, Edwin Coomasaru, associate lecturer at London’s Courtauld Institute of Art, interprets the same fear, a lingering nervousness, beneath the bravado on show in Knorr’s Gentlemen which, alongside images, includes quotes and phrases from her subjects. Coomasaru writes that “anxiety creeps into the proclamations of custodianship. The breakup of the British empire haunts such bravado; it is as though the speakers are struggling to adjust to the UK’s loss of influence on the world stage.”

“When the Rule of law Breaks / down, the World takes a further step towards Chaos,” reads one of Knorr’s captions, the words of a man in a suit photographed near St James’s Palace, London. Today, a text like this could be read as defending a man accused of sexual assault on social media but never prosecuted. Or criticizing the current protests against racism and police brutality, the couple of days of looting, the overall urgency. Another step towards chaos? Or a step towards his own irrelevance?

© the artist

It is strange to think of the conversations happening when this show was first conceived and those occurring when it reopens. George Floyd murdered. Black Lives Matter activists marching. The US president even more tyrannical. The police again exposed for their racism and violence. And man proven powerless against a virus. The enormity of it all.

In his 1985 essay “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood,” cited repeatedly in the Masculinities book, James Baldwin writes that the American ideal of masculinity “has created cowboys and Indians, good guys and bad guys, punks and studs, tough guys and softies, butch and faggot, black and white.” He also writes: “Violence has been the American daily bread since we have heard of America. This violence, furthermore, is not merely literal and actual but appears to be admired and lusted after, and the key to the American imagination.” The recent, unbearable visibility of that lust—the sense of self that a police officer seemed to draw from placing his knee on the neck of an already restrained Floyd—should make us see all the pictures in Masculinities, and the power balances and struggles they purportedly show, afresh. If Masculinities is a battle cry against the tyranny of hegemonic masculinity, then mere liberation is one solution. But in recent weeks, there have been many others, more radical and more compelling in their urgency.

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography is on view at Barbican Art Gallery, London, through August 23, 2020.